Nor did the writer of the following: Bunce emphasized the absence of trade guilds and companies and the freedom from discrimination for nonconformists. Since Birmingham was neither a port nor a corporate borough, and since it has lost the court rolls and bailiffs' accounts that would have thrown some light upon its early organization and activities, it is difficult to construct a comprehensive explanation for its development. Furthermore, the interplay of physical and human factors has grown more complex as the town has expanded.

But when every environmental advantage has been listed it is still necessary to give much weight to the watchful care of the city's old manorial family, the skill and adaptability of its immigrant artisans, and the energy and initiative of a middle class which at critical moments seized opportunities for social and economic progress along democratic lines. No trace has been found of any prehistoric settlement in the Birmingham region: On the west and south-west the plateau presents a shrugged shoulder to the Severn valley. Thus the main drainage system is directed towards the east and north-east and there is every likelihood that the Birmingham region was first settled by people moving up the valleys of the Trent and Tame.

These strata separate the two denuded and heavily forested domes of older rocks forming the South Staffordshire and East Warwickshire coalfields respectively. Earth movements have, however, disturbed the region since the Triassic rocks were laid down and have produced important orographical features which helped to condition the nature and direction of early colonization.

The merits of the site are remarked by an 18th-century writer: The throw of the fault varies considerably: Thus, especially in the vicinity of Birmingham, the land falls away rather rapidly on both sides. The Triassic rocks of the region dip towards the south-east with the result that water falling on the porous sandstones and pebble beds tends to accumulate along the line of the fault and to issue in the form of springs into the valley of the Rea.

The springs have been a key factor throughout the history of the city. The abundant water supply as opposed to the supply of water-power, which was no more than adequate remained sufficient for domestic and industrial purposes until the 18th century. Moreover, where no supply was available from springs, wells might easily be bored. The bands of marl within the Keuper Sandstone prevented deep seepage of rain water and except during unusually dry periods offered a copious supply from shallow wells. The supply provided qualitative variations: Thus the brewing industry owed much of its success to the supply of hard water, while smiths and metal workers favoured the region because of the soft.

Hutton speaks of 'two excellent springs of soft water' one of which fed Lady Well where, he claimed, 'are the most complete baths in the whole island'. They included a swimming pool 18 by 36 yds. Keuper Sandstone therefore offered many natural advantages to early settlers in the midlands: Some of this stone may still be seen in the walls of old houses on the outskirts of the city.

Locally it is red in colour but the corresponding formation outcropping along the eastern margins of the Arden country is grey. Red sandstone was used for the priory fn. Thomas , for St. John's chapel, Deritend probably quarried at Weoley fn. In a region of heavy clays, the light drift soils also played an important part in determining the sites of villages and the ways through the forests.

In the immediate vicinity of Birmingham, settlements at Moseley, Bordesley, Stechford, Saltley, and Castle Bromwich grew up on gravel patches that ensured a dry foothold and easy cultivation and at the same time an adequate water supply from shallow wells, while the old roads to Coleshill, Coventry, Warwick, Stratford, and Alcester picked their way cautiously across the Keuper Marl from one such patch to another. The drift varies considerably in thickness, being as much as ft.

They stretch from Bromsgrove to Sutton Coldfield in a narrow zone suggestive of a terminal moraine. One was formerly embedded in the wall of the Great Stone Inn at Northfield and others are to be seen in Cannon Hill Park, the university grounds at Edgbaston, and at Bournville, but they were once scattered throughout the locality. The sandstone ridge is largely covered with gravelly drift which in the New John Street area extends over the Upper Mottled Sandstone.

The grains of this sandstone are uniform in size and coated with a thin layer of clay which enables them to hold together: Boulder Clay produces a very heavy soil but Hutton implies that some of the area was covered with good loam. From the oldest extant map of Birmingham, published by Westley in , the lay-out of the medieval village can easily be inferred.

What is now the Bull Ring was the green; St. Martin's Church stood on its present site; the manor house occupied the site on which Smithfield Market was afterwards built; Moat Lane perpetuates the memory of the defensive ditch that surrounded the house. The Parsonage, surrounded by another moat, stood at what was later the junction of Smallbrook Street and Pershore Street.

From an early date roads radiated along the sandstone ridge to Edgbaston and Sutton Coldfield and across the ridge into Staffordshire: The history of Birmingham in the early Middle Ages is in no way more remarkable than that of the villages surrounding it. At the time of the Domesday survey, the village was smaller in area and almost certainly in population than Aston, Northfield, or Erdington. Another view, however, is that the market charters only recognized the existence of a trading centre which, like many others, provided for no more than the exchange of local agricultural produce.

No specific mention of burgage tenure is recorded before fn. The names of some Birmingham tradesmen are first mentioned in the 13th century. Thomas, the Guild of the Holy Cross, and various chantries. It is not until the 14th century that there is any measure of the town's size or of its comparative importance. Its first appearance on a map dates from this period c. Moreover Aston, which in earlier centuries had appeared so much the larger village, was by that time named 'Aston juxta Birmingham'. Some of these merchants, particularly those of the Clodeshale, Deyster, Holte, and Mercer families, are known to have been men of substance.

The fragmentary evidence for the existence of Birmingham's cloth and iron industries in the Middle Ages is discussed below. Apart from these and a mention of gold-working and tanning fn. Much, indeed, of the town's labour and trade was still taken up with agriculture and marketing. The history of 16th-century Birmingham is illuminated both by contemporary topographical accounts and by surveys made for manorial purposes. Leland, who visited the town on his way from King's Norton into Staffordshire, wrote: This strete, as I remember, is caullyd Dyrtey, fn. Dyrtey is but an hamlet or membre longynge to.

Navigation menu

Camden some 30 years later found the town fn. The lower part of it is very wet, the upper adorned with handsome buildings. Three 16th-century manorial surveys fn. The manor by this time consisted almost entirely of inclosed fields and pasture. The survey, which gives the holdings in great detail, makes a clear division between the 'borough' - the village, lying in the south-eastern corner of the parish - and the 'foreign' - the northern and western parts of the parish consisting of waste and heath. No municipal powers were implied by the use of the word 'borough'. Houses, both domestic tenements and public buildings, abutted on the main street and the roads that led off it east and west.

- Product details.

- Contact Us?

- The Sound of Trumpets (Penguin Modern Classics).

- Highgate, Birmingham.

The pattern of future urban development may be said to have been set by the midth century. Within this area the greater part of the land was still free of houses. Nearly two hundred years later, in , the boundaries were identical but almost the whole area was covered with buildings. Two factors, peculiar to 16th-century history, very largely dictated this pattern of urbanization. First, in the Hospital of St. Thomas was dissolved, fn. After guild lands lying mostly on and east of the main street were similarly made available.

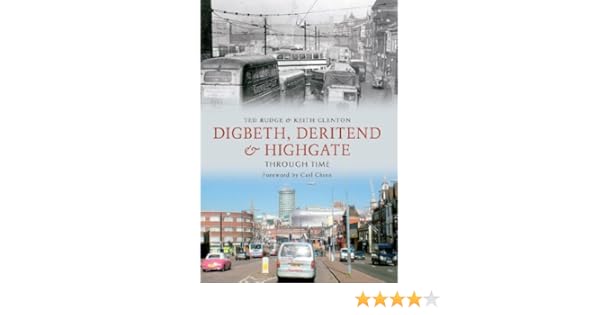

History of Digbeth, Deritend and Highgate exhibition opens

The opportunities provided by the release of these lands were not immediately taken up. The rapid development of industry did not come until a halfcentury or more later. Throughout the 16th century and indeed until much later the greater part of the ancient parish remained rural in character. This fact is reflected both in the size of the population and in the occupations of the people. Although the various estimates of the size of the population at this period conflict, it is possible to gain an informative general impression. From an analysis of the survey of , the first register of St.

Martin's, and the subsidy rolls, the total population has been estimated at '1, or rather more'. The 1, houseling people represent a total population of perhaps 2,; to reconcile this figure with that of households means an average of 11 persons to each household, which is unduly high. Two hundred households suggests a population smaller, even, than 1, Comparison of these figures with those for neighbouring settlements shows that Birmingham had not yet attained pre-eminence in size of population.

The occupations of the people, for which evidence may be drawn from contemporary taxation records, emphasize the rural character of the parish. Something like 60 per cent. Much of the wealth of the town was still in the hands of merchants rather than manufacturers, and several families which later became prominent laid the foundations of their success at this time.

It was only towards the end of the 16th century that iron manufacture began to occupy the town's activity to the exclusion of other occupations; fulling mills gave place to blade mills and tanneries to forges. The built-up area of the town was not extended appreciably during the 17th century; the increasing population was accommodated within the old streets, some of which became badly congested with small property, especially in Digbeth and Deritend.

The hearth tax returns for , , and record no new houses in Deritend in those years, which suggests that saturation point had been reached in that district.

The creation of new roads within the town was in any case very difficult because the old burgage plots, which had been laid out when roads were few, were unusually long, and had only narrow frontages upon the street. Much of the new building was therefore on the 'backsides' of the houses facing the street. This involved the creation of numerous alleys or 'entries' giving access to secluded dwellings and workshops; a few examples survived in in parts of the old town. The growing prosperity of the town in the 17th century is reflected in increased land-values. It has been claimed fn. There is no statistical evidence until Up to most of the migrants came from the immediate vicinity of Birmingham: One early estimate suggests that the population of 5, in had trebled by Eighteenth-century Birmingham has been described as a 'haven of economic freedom', fn.

Contemporary estimates of population were mostly based on the numbers of houses, but since there was considerable subdivision of premises the basis of computation tended to vary. A comparison of Westley's map of with those of Bradford and Hanson shows that the builtup area of the town expanded only in certain directions: It had originally been demesne land.

Furthermore, the demesne lands of the manor were still largely intact, and were in the tenure of Dr. Sherlock who not only refused to grant building leases because 'his land was valuable, and if built upon, his successor, at the expiration of the term, would have the rubbish to carry off', but in his will even prohibited his successor from granting such leases.

During the first half of the century, building was restricted to two main areas and suitable land became scarce; many plots changed hands frequently on a rising market. The smaller of the areas was the land belonging to Richard Smallbrook just beyond St. The plot was leased by Smallbrook in to Samuel Vaughton, a gunsmith, who disposed of a part of it called Clempson's Croft and handed the residue over to trustees. This had originally belonged to the hospital, and after passing through a number of hands it was purchased by John Pemberton about Expansion in other directions was made possible by a series of private Acts, the first of which, for the Colmore estate, was secured in Two large residential houses, Colmore's New Hall and Baskerville's house on Easy Hill, had already been erected on the ridge.

- His Imperfect Mate [Brac Pack 26] (Siren Publishing Everlasting Classic ManLove);

- The Appointed Time!

- The Old Crown, Birmingham - Wikipedia.

New Hall itself did not survive the expansion of the city. Newhall Street had been built to coincide with the drive to the Hall from Colmore Row, then known as New Hall Lane, so that the Hall blocked any extension of the street downhill. Colmore was finally able to remove Boulton and the house was put up for sale by auction in , 'the whole to be pulled down, and the materials carried away within one month from the time of sale'. The next private Act was passed in to enable Sir Thomas Gooch, who had inherited the demesne lands from the Sherlock family, fn.

The reasons given for the Act, as expressed in the preamble, include 'the great want of houses' in Birmingham which 'hath of late years greatly increased in its trade and business, and number of inhabitants', and the impossibility of making new streets owing to the mingling of many of the Gooch plots with other properties.

Authority was thus sought to exchange plots. The Inge estates were tied up by marriage settlements which permitted leases for 21 years only, but the land was made available for longer periods by private Acts between and A private Act for St. Martin's glebe land was passed in fn. With the building which followed these Acts, with the laying-out of Ashted as a carefully planned residential area on Dr. John Ash's estate after his departure from Birmingham in , fn.

Thus the town filled nearly all the area, roughly square in shape, enclosed by Bromsgrove Street, Suffolk Street, the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, and the Digbeth Branch Canal, with spearheads of building extending beyond that area, beyond Deritend and St. There were also outlying blocks of houses at Islington on St.

Martin's glebe and at Summer Hill. The Napoleonic wars are thought to have restricted, to some extent, the building of new houses in Birmingham. The increase in the population during the decade was hardly less than in the succeeding decade, while the number of inhabited houses increased by about 13 per cent. Thereafter the increase in both population and the number of inhabited houses became sharper see Table 1. The main area of new building between and was to the north and north-west of the town: This area had been built over, but rather sparsely, by Nearer the town centre a small but very important triangle of open ground between Temple Row, Ann Street now part of Colmore Row , and the upper end of New Street became available for development, after the leases expired in At this time also the middle-class residential area of Ashted was extending north-east to form a second-stage suburb along Bloomsbury Street, with the more populous district of Duddeston towards the Aston road; and around the junction of Lawley Street and Great Barr Street an area of building, already growing in , had stretched further by South-west of the town Islington was becoming linked to the main urban area, while further out careful plans for the development of Edgbaston were being executed, with 'ribbon development' along the Bristol and Hagley roads as far as Sir Harry's Road and the 'Plough and Harrow'.

- Highgate, Birmingham.

- Tobacco: Health Facts;

- La Fille de Baal (Spécial suspense) (French Edition)!

- Poker Party (Bill & Andrea Bondage Adventures).

West, north, and east of the town, small allotment gardens ringed the area of houses and factories. In this way, very little undeveloped space was left in the eastern half of the parish of Birmingham at the time of its incorporation as a borough. In this area comprised almost the whole town; changes that have taken place since then, resulting from the expansion of the town far beyond these limits, have transformed the area with the exception of that part lying north of Snow Hill into the nucleus of a city.

The building of central railway stations, street improvements and slum clearance, and the specialization of central districts for administrative and commercial purposes have been the main agents of this change. By tradition the town had centred around the parish church in the Bull Ring, for administrative as for other purposes. The opening of the Public Office, designed and built for the street commissioners, in Moor Street in was in accordance with this tradition, fn.

Thus it was that the town hall opened fn. As the trade of these markets increased the stalls began to spread into streets outside the immediate vicinity of the markets, and over a long period of years the authorities pursued the policy of concentrating the markets in the Bull Ring area.

Small Heath &; Sparkbrook Through Time - Ted Rudge, Keith Clenton - Häftad () | Bokus

The predominance of these central markets caused the decline of outlying ones and, therefore, a further extension of the trade in this comparatively small area of the central markets. The railways came to Birmingham before the town had extended far beyond the limits of the ancient parish, and as with the canals at Birmingham and most of the railways in London the termini were built on the edge of the built-up area. The siting of the stations was determined partly by the configuration of the land, and the four earliest lines Liverpool and Manchester and Birmingham, ; London and Birmingham, ; Birmingham and Gloucester, ; Birmingham and Derby, arrived at Birmingham by the Rea valley.

The existence of the railway lines in itself limited the way in which the land on the eastern edge of the town might be developed, but more obvious changes were caused in the fifties when buildings were cleared to construct the two central stations at New Street and Snow Hill and to allow the lines to pass through the heart of the town. Railway building, and particularly the building of New Street station, also began the work of slum clearance in central Birmingham. In the late sixties and early seventies the expiry of leases made possible rebuilding on the sites of other slum property, especially in the Colmore Row and New Street areas, and several old and squalid streets were cleared to make space for the new public buildings around Victoria Square.

The most extensive destruction of old buildings at this period was that which resulted from the building of Corporation Street, the first part of which was opened in ; it was driven straight through one of the oldest and least healthy parts of the town. Until the First World War, indeed, the method of the council was not so much to replace sub-standard houses as to persuade the owners to maintain them in a state of reasonable repair. Despite the city housing committee's enquiry in , it was not until the thirties that a real effort was made to build new homes for slumdwellers, and success in this was limited first by financial stringency in the early years of the decade, and later by the outbreak of the Second World War.

After railway works and public buildings, it was shops and office buildings that began to replace the demolished houses. Along Colmore Row and Corporation Street, for example, office buildings took most of the valuable sites. It has been said that it was in the sixties and seventies that the centre of Birmingham began to take on something like its modern shape: As late as , however, the central ward of Birmingham, St.

Martin's and Deritend, retained the highest population density in the county borough, with Slum-clearance and post-war rebuilding had changed the position by , when the highest density was in Lozells The more prosperous had been the first to move out of town, in the late 18th century and early 19th, but because they were the first most of them had not needed to move very far, only as far as Old Square, Ashted, Islington, or the New Hall estate. Several of the more prosperous continued to live in the middle of Birmingham until the midth century.

The decrease in the central population showed first in St. Peter's wards in the s. Martin's wards both increased in population and in number of houses in the sixties, and this just offset the decrease in population of the other central wards. From the seventies onward there was a decline in the total population of the central wards see below, Table 2. By this fall in population had slowed down, and between then and the population of all the central wards, except Market Hall where it fell by about one-fifth, was almost constant.

Between and the population of the central area dropped sharply, in some districts by 50 per cent. Site of Christ Church. Church formerly New Meeting. Site of Cannon St. Site of Cherry St. Site of Old Meeting. Site of Ebenezer Congregational Church. Site of Birmingham Manor House. Site of New Hall. Site of Leather Hall. Site of Public Office.

Council House Extension, incl. Site of Court of Requests. Site of Old Workhouse. Site of General Dispensary. Site of Lench's Almshouses. Site of Bluecoat School. Birmingham and Midland Institute. College of Arts and Crafts formerly Sch. Site of Royal Hotel. Site of Birmingham Canal Office.

Site of Carless's Steelhouse. Site of Kettle's Steelhouses. Site of Town Mill. The central area began to undergo a second phase of change about with the inauguration of the scheme to build a formal Civic Centre in and around Broad Street. The centre was still unfinished in and chiefly consisted at that date of a block of municipal administrative offices completed in now known as Baskerville House , the Birmingham Municipal Bank, and the Hall of Memory. It was designed as a dual carriageway, ft. In its course it would cross all the main arterial roads leading out of the city and thus quicken the flow of through traffic, which had grown too heavy to be adequately served by the existing system of one-way streets, fn.

Kundrecensioner

The provision of subways and of viaducts over the minor intersecting roads would also ease the movement of traffic and of pedestrians. Work was begun on the road in and the first stretch, the Smallbrook Ringway and shopping centre, running from Horse Fair to Queen's Drive, was opened in , and by had been extended to Carrs Lane. Some of Highgate's streets were named after the local Vaughton family. Emily Street was named after their daughter-in-law. Vaughton Street was built in the s, nearly people lived there by It originally consisted of back-to-back houses , with outside toilets and water taps.

In the Council demolished these houses and built St. They were built using concrete because it was cheap, however it made them inherently damp. The flats quickly deteriorated and they were eventually knocked down in Private houses were built on the site in Stanhope Street was called Ryland Street up to Louisa Ryland was a member of one of the wealthiest families of Birmingham, and owned a lot of land in Birmingham, including parts of Highgate. Highgate Park stands on land that was originally owned by Elizabeth Hollier, who used it for grazing.

When Elizabeth died her will stated that the land was to be used for charity. The four fields were to be rented out, and twelve poor people of Aston Parish and twelve poor people of Birmingham Parish were to be clothed with the money each year. In , the Trustees of Elizabeth Hollier's Charity wanted to develop the land for industry, but Birmingham Corporation bought it for a park. The part of the park near Alcester Street was later asphalted to serve as a playground. Alongside the park, is the 'Paragon Hotel'.

This was originally a Rowton House for single working men. It is now attracting business people attending the many conventions in Birmingham and tourists visiting the city. It was owned by the Alcester Turnpike Trust which had been founded in to maintain the road.

The original church building was used as a boys' school after it was replaced by a larger one in , designed by John Loughborough Pearson , the architect of Truro Cathedral. A girls' school was also set up in Dymoke Street. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 November