This view that rehearsal is actually important has been opposed recently. Repetition of each item as it is presented? In the case of using attention to refresh information, an interesting case can be made. Children who are too young about 4 years of age and younger do not seem to use attention to refresh items. For them, the limit in performance depends on the duration of the retention interval.

For older children and adults, who are able to refresh, it is not the absolute duration but the cognitive load that determines performance Barrouillet et al. There are reasons to care about whether the growth of capacity is primary, or whether it is derived from some other type of development. For example, if the growth of capacity results only from the growth of knowledge, then it should be possible to teach any concept at any age, if the concept can be made familiar enough.

If capacity differences come from speed differences, it might be possible to allow more time by making sure that the parts to be incorporated into a new concept are presented sufficiently slowly. We have done a number of experiments suggesting that there is something to capacity that changes independent of these other factors. Regarding knowledge, relevant evidence was provided by Cowan, Nugent, Elliott, Ponomarev, and Saults in their test of memory for digits that were unattended while a silent picture-rhyming game was carried out.

The digits were attended only occasionally, when a recall cue was presented about 1 s after the last digit. The performance increase with age throughout the elementary school years was just as big for small digits 1, 2, 3 , which are likely to be familiar, as for large digits 7, 8, 9 , which are less familiar.

Gilchrist, Cowan, and Naveh-Benjamin further examined memory for lists of unrelated, spoken sentences in order to distinguish between a measure of capacity and a measure of linguistic knowledge. The measure of capacity was an access rate, the number of sentences that were at least partly recalled. The measure of linguistic knowledge was a completion rate, the proportion of a sentence that was recalled, provided that at least part of it was recalled. Nevertheless, the number of sentences accessed was considerably smaller in first-grade children than in sixth-grade children about 2.

I conclude, tentatively at least, that knowledge differences cannot account for the age difference in working memory capacity. We have used a different procedure to help rule out a number of factors that potentially could underlie the age difference in observed capacity.

On each trial of this procedure, an array of simple items such as colored squares is presented briefly and followed by a retention interval of about 1 s, and then a single probe item is presented. The latter is to be judged identical to the array item from the same location, or a new item. This task is convenient partly because there are mathematical ways to estimate the number of items in working memory Cowan, It is possible to calculate k , which for this procedure is equal to N h-f , where h refers the proportion of change trials in which the change was detected hits and f refers to the proportion of no-change trials in which a change was incorrectly reported false alarms.

One possibility is that younger children remember less of the requested information because they attend to more irrelevant information, cluttering working memory for adults, cf. When there were 2 triangles and 2 circles, memory for the more heavily-attended shape was better than memory for the less-attended shape, to the same extent in children in Grades 1—2 and Grades 6—7, and in college students.

Yet, the number of items in working memory was much lower in children in Grades 1—2 than in the two older groups. It did not seem that the inability to filter out irrelevant information accounted for the age difference in capacity. Another possibility is that in Cowan et al. The results remained the same as before. It appears that neither encoding speed nor articulation could account for the age differences. So we believe that age differences in capacity may be primary rather than derived from another process.

- .

- Working Memory Underpins Cognitive Development, Learning, and Education.

- .

- Bluegrass Songbook: Guitar Play-Along Volume 77?

Alternatively, it could occur because of age differences in some other type of speed, neural space, or efficiency. This remains to be seen but at least we believe that there is a true maturational change in working memory capacity underlying age differences in the ability to comprehend materials of different complexity. This is in addition to profound effects of knowledge acquisition and the ability to use strategies.

The use of strategies themselves may be secondary to the available working memory resources to carry out those strategies. According to the neoPiagetian view of Pascual-Leone and Smith , for example, the tasks themselves share resources with the data being stored. The attentional resource allocated to the items in the array was apparently deducted from the resource available to allocate attention optimally. In practical terms, it is worth remembering that several aspects of working memory are likely to develop: Although it is not always easy to know which process is primary, these aspects of development all should contribute in some way to our policies regarding learning and education.

In early theories of information processing, up through the current period, working memory was viewed as a portal to long-term memory. In order for information to enter long-term memory in a form that allows later retrieval, it first must be present in working memory in a suitable form. Sometimes that form appears modality-specific. For example, Baddeley, Papagno, and Vallar wondered how it could be that a patient with a very small verbal short-term memory span, 2 or 3 digits at most, could function so well in most ways and exhibit normal learning capabilities.

The answer turned out to be that she displayed a very selective deficit: Aside from this specific domain, there are several ways in which working memory can influence learning. It is important to have sufficient working memory for concept formation. The control processes and mnemonic strategies used with working memory also are critical to learning. Learning might be thought of in an educational context as the formation of new concepts. These new concepts occur when existing concepts are joined or bound together. Some of this binding is mundane. If an individual knows what the year means and also what the Declaration of Independence is at least in enough detail to remember the title of the declaration , then it is possible to learn the new concept that the Declaration of Independence was written in the year Other times, the binding of concepts may be more interesting and there may be a new conceptual leap involved.

For example, a striped cat is a tiger. As another simple example, to understand what a parallelogram is, the child has to understand what the word parallel means, and further to grasp that two sets of parallel lines intersect with one another. The ideas presumably must co-exist in working memory for the concept to be formed. For the various types of concept formation, then, the cauldron is assumed to be working memory.

According to my own view, the binding of ideas occurs more specifically in the focus of attention. We have taken a first step toward verifying that hypothesis. Cowan, Donnell, and Saults in press presented lists of words with an incidental task: Later, participants completed a surprise test in which they were asked whether pairs of words came from the same list; the words were always one or two serial positions apart in their respective lists, but sometimes were from the same list and sometimes from different lists.

The notion was that the link between the words in the same list would be formed only if the words had been in the focus of attention at the same time, which was much more likely for short lists than for long lists. This is a small effect, but it is still important that there was unintentional learning of the association between items that were together in the focus of attention just once, when there was no intention of learning the association. The theory of Halford et al. More complex concepts require that one consider the relationship between more parts.

It may be possible to memorize that concept with less working memory, but not truly to understand the concept and work with it. Take, for example, use of the concept of transitivity in algebra. Yet, a person who understands the rules of algebra still would not be able to draw the correct inference if that person could not concurrently remember the two equations. Even if the equations are side by side on the page, that does not mean that they necessarily can be encoded into working memory at the same time, which is necessary in order to draw the inference.

Lining up the equations vertically for the learner and then inviting the learner to apply the rule by rote is a method that can be used to reduce the working memory load, perhaps allowing the problem to be solved. However, working out the problem that way will not necessarily produce the insight needed to set up a new problem and solve it, because setting up the problem correctly requires the use of working memory to understand what should be lined up with what.

So if the individual does not have sufficient working memory capacity, a rote method of solution may be helpful for the time being. More importantly, though, the problem could be set up in a more challenging manner so that the learner is in the position of having to use his or her working memory to store the information.

By doing so, the hope is that successful solution of the problem then will result in more insight that allows the application of the principles to other problems. That, in fact, is an expression of the issues that may lead to the use of word problems in mathematics education. Researchers appear to be in fairly good agreement that one of the most important aspects of learning is staying on task. If one does not stick to the relevant goals, one will learn something perhaps, but it will not be the desired learning.

Individuals who test well on working memory tasks involving a combination of storage and processing have been shown to do a better job staying on task. A good experimental example of how staying on task is tied to working memory is one carried out by Kane and Engle using a well-known task designed long ago by John Ridley Stroop. In the key condition within this task, one is to name the color of ink in which color words are written. Sometimes, the color of ink does not match the written color and there is a tendency to want to read the word instead of naming the color.

This effect can be made more treacherous by presenting stimuli in which the word and color match on most trials, so that the participant may well lapse into reading and lose track of the correct task goal naming the color of ink. What that happens, the result is an error or long delay on the occasional trials for which the word and ink do not match.

Under those circumstances, the individuals who are more affected by the Stroop conditions are those with relatively low performance on the operation span test of working memory carrying out arithmetic problems while remembering words interleaved with those problems. In more recent work, Kane et al. Participants carried devices that allowed them to respond at unpredictable times during the day, reporting what they were doing, what they wanted to be doing, and so on. It was found that low-span individuals were more likely to report that their minds were wandering away from the tasks on which they were trying to focus attention.

This, however, did not occur on all tasks. The span-related difference in attending was only for tasks in which they reported that they wanted to pay attention. When participants reported that they were bored and did not want to pay attention, mind-wandering was just as prevalent for high spans as for low spans. Although this work was done on adults, it has implications for children as well. Gathercole, Lamont, and Alloway suggest that working memory failures appear to be a large part of learning disabilities. Children who were often accused of not trying to follow directions tested out as children with low working memory ability.

They were often either not able to remember instructions or not able to muster the resources to stick to the task goal and pay attention continually, for the duration needed. Of course, central executive processes must do more than just maintain the task goal. The way in which information is converted from one form to another, the vigilance with which the individual searches for meaningful connections between elements and new solutions, and self-knowledge about what areas are strong or weak all probably play important roles in learning.

There also are special strategies that are needed for learning. For example, a sophisticated rehearsal strategy for free recall of a list involves a rehearsal method that is cumulative. If the first word on the list is a cow, the second is a fish, and the third a stone, one ideally should rehearse cumulatively: Cowan, Saults, Winterowd, and Sherk showed that young children did not carry out cumulative rehearsal the way older children do and could not easily be trained to do so, but that their memory improved when cumulative rehearsal was overtly supported by cumulative presentation of stimuli.

For long-term learning, maintenance rehearsal is not nearly as effective a strategy as elaborative rehearsal, in which a coherent story is made on the basis of the items; this takes time but results in richer associations between items, enhancing long-term memory provided that there is time for it to be accomplished e. In addition to verbal and elaborative rehearsal, Barrouillet and colleagues have discussed attentional refreshing as a working-memory maintenance process.

We do not yet know what refreshing looks like on a moment-to-moment basis or what implications this kind of maintenance strategy has for long-term learning. It is a rich area for future research. The most general mnemonic strategy is probably chunking Miller, , the formation of new associations or recognition of existing ones in order to reduce the number of independent items to keep track of in working memory. The power of chunking is seen in special cases in which individuals have learned to go way beyond the normal performance. Ericsson, Chase, and Faloon studied an individual who learned, over the course of a year, to repeat lists of about 80 digits from memory.

He learned to do so starting with a myriad of athletic records that he knew so that, for example, might be recoded as a single unit, 3. After applying this intensive chunking strategy in practice for a year, a list of 80 digits could be reduced to several sub-lists, each with associated sub-parts. The idea would be that the basic capacity has not changed but each working-memory slot is filled with quite a complex chunk. In support of this explanation, individuals of this sort still remain at base level about 7 items for lists of items that were not practiced in this way, e.

Although we cannot all reach such great heights of expert performance, we can do amazing things using expertise. For example, memorization of a song or poem is not like memorization of a random list of digits because there are logical connections between the words and between the lines.

- Awakening, Becoming A Brain Tumor Thriver.

- Law School Ninja.

- Die deutsch-polnischen Beziehungen von 1918 bis 1933 (German Edition)!

- Working Memory Underpins Cognitive Development, Learning, and Education.

- INTRODUCTION.

A little working memory then can go a long way. The importance of a good working memory comes in when something new is learned, and logical connections are not yet formed so the working memory load is high. When there are not yet sufficient associations between the elements of a body of material, working memory is taxed until the material can be logically organized into a coherent structure. Working memory is thought to correlate most closely with fluid intelligence, the type of intelligence that involves figuring out solutions to new problems e.

However, crystallized intelligence, the type of intelligence that involves what you know, also is closely related to fluid intelligence. The path I suggest here is that a good working memory assists in problem-solving hence fluid intelligence ; fluid intelligence and working memory then assist in new learning hence crystallized intelligence.

We have sketched the potential relation between working memory and learning. How is that to be translated into lessons for education? There is a large and diverse literature on this topic. As a starting point to illustrate this diversity, I will describe the chapters chosen for the book, Working memory and education Pickering, After an introductory chapter on working memory A. Baddeley , the book includes two chapters on the relation between working memory and reading one by P. There is a chapter on the relation between working memory and mathematics education R.

Espy , learning disabilities H. Swanson , attention disorders K. Cornish and colleagues , and deafness M. Other chapters cover more general topics, including the role of working memory in the classroom S. Gathercole and colleagues , the way to assess working memory in children S. Pickering , and sources of working memory deficit M.

It is clear that many avenues of research relate working memory to education, and I cannot travel along all of them in this review. To organize a diverse field, what I can do is to distinguish between several different basic approaches have been tried. The points described in the article up to this point should be kept in mind when one is trying to discern and understand what a particular learner can and cannot do.

Second, one can try to use training exercises to improve working memory, which, investigators have hoped, would allow a person to be able to learn more and solve problems more successfully. The message I would give here is to be wary, given the rudimentary state of the evidence in a difficult field and the plethora of companies selling working memory training exercises. Third, one might contemplate the role of working memory for the most critical goals of education, in a broad sense.

These topics will be examined one at a time. The classic adaptation of education to cognitive development and the needs of learning has been to try to adjust the materials to fit the learner. For example, there has been considerable discussion of the need to delay teaching concepts of arithmetic at least until the children understand the basic underlying concept of one-to-one correspondence; that is, the idea that there are different numbers in a series and that each number is assigned to just one object, in order to count the objects e. There also are individual differences within an age group in ability that affect how the materials are processed.

The enjoyment of technological presentations may be greater in students with better abilities in the most relevant types of working memory e. The theory distinguishes between an intrinsic cognitive load that comes from material to be learned and an extraneous cognitive load that should be kept small enough that the cognitive resources of the learner are not overly depleted by it. This theory has the advantage of being rather nuanced in that many ramifications of cognitive load are considered. With too high a cognitive load, one runs the risk of the student not being able to follow the presentation, whereas with too low a cognitive load, one runs the risk of insufficient engagement.

In future, it might be possible to refine the predictions for classroom learning by combining cognitive load theory with theories of cognitive development, which make some specific predictions about how much capacity is present at a particular age in childhood e. Issues arise as to how printed items are encoded visually, verbally, or both and how much the combination of verbal and visual codes in multimedia should be expected to tax a common, central cognitive resource and therefore interfere with one another, even when they are intended to be synergic.

Both in cognitive psychology and in education, these are key issues currently under ongoing investigation. This might be done partly on the basis of success; if the student succeeds, the materials can be made more challenging whereas, if the student fails, the materials can be made easier. One potential pitfall to watch for is that, while some students will want to press slightly beyond their zone of comfort and will learn well, others will want an easy time, and may choose to learn less than they would be capable of learning.

One way to cope with these issues is through computerized instruction, but with a heavy dose of personal monitoring and adjustment to make sure that the task is sufficiently motivating for every student. There are several obstacles in this regard. Slevc showed that speakers tend to blurt out what is most readily available in working memory. He used situations that were to be described verbally by the participant, e.

If one piece of information had already been presented, it was more likely to be described first. For example, if the monk had been presented already but not the book, the participant was more likely to phrase the description differently, as A pirate gave the monk a book. This assignment of priority to given information is generally appropriate, given that the speaker and listener or writer and reader share the same given information. In this case, though, Slevc shows that the tendency to describe given information first was diminished when the speaking participant was under a working memory load.

In a didactic situation such as giving a lecture, it thus seems plausible that the memory load inherent in the situation remembering and planning what one wants to say in the coming segments of a lecture may cause the lecturer sometimes to use awkward grammatical structure. Moreover, as mentioned above, learning to speak or write well requires that one bear in mind possible difference between what one knows as the speaker or writer and what the listener or reader knows at key moments. Bearing in mind what the listener or reader knows and does not yet know is likely to be important both for educators in their own speaking and writing, and also in order to teach students how to speak and write effectively.

A much more controversial approach is to use training regimens to improve working memory, thereby improving performance on the educational learning tasks that require working memory e. It is controversial partly because many people have spent a great deal of money purchasing such training programs before the scientific community has reached an agreement about the efficacy of such programs.

Doing working memory training studies is not easy.

Forgot Password?

One needs a control group that is just as motivated by the task as the training group but without the working memory training aspect. The training task must be adaptive with rewards for performance that continues to improve with training and a non-adaptive control group does not adequately control arousal and motivation. Some task that is adaptive but involves long-term learning instead of working memory training may be adequate.

Several large-scale reviews and studies have suggested that working memory training sometimes improves performance on the working memory task that is trained, but does not generalize to reasoning tasks that must rely on working memory in adults, Redick et al. In somewhat of a contrast, other reviews suggest that the training of executive functions inhibiting irrelevant information, updating working memory, controlling attention, etc. So there is an ongoing controversy, even among those who have written meta-analyses and reviews of research.

One might ask how it is possible to improve working memory without having the effect of improving performance on other tasks that rely on working memory. This can happen because there are potentially two ways in which training can improve task performance. First, working memory training theoretically might increase the function of a basic process, much as a muscle can be strengthened through practice.

Or at least, individuals might learn that through diligent exertion of their attention and effort, they can do better. That is presumably the route hoped for in training of working memory or executive function. Second, though, it is possible for working memory training to result in the discovery of a strategy for completing the task that is better than the strategy used initially. This can improve performance on the task being trained, but the experience and the strategy learned may well be irrelevant to performance on other educational tasks, even those that rely on working memory.

This route might be expected if, as I suspect, participants typically look for a way to solve a problem that is not very attention-demanding, unless the payoff is high. If there is successful working memory training, another issue is whether training is capable of producing super-normal performance or whether it is mostly capable of rectifying deficiencies. By way of analogy, consider physical exercise.

If a person is already walking 6 miles a day, there might be little benefit to the heart of adding aerobic exercise. Similarly, if a person is already highly engaged in the environment and using attention control often and effectively during the day, there might be little benefit to the brain of adding working memory exercises. It remains quite conceivable, though, that such exercises are beneficial to certain individuals who are under-utilizing working memory. Nevertheless, as Diamond and Lee points out, there might be social or emotional reasons why this is the case and such factors would need to be addressed along with, or in some cases instead of, working memory training per se.

What is the difference between learning and education? This is a question that has long been asked for a history of the early period of educational psychology in the United States, for example, see Hall, Do children learn better when they are fed the information intensively, or allowed to explore the material? Should all children be expected to learn the same material, or should children be separated into different tracks and taught the information that is thought to help them the most in their own most likely future walks of life?

A fundamental difference between learning and education, many would agree, is that education should facilitate the acquisition of skills that will promote continued learning after the student leaves school. Of course, after the student leaves school, a major difference is that there is no teacher to decide what is to be learned, or how. Therefore, what seems to be most important, many would agree, is critical thinking skills. For example, Halpern p. For example, Shim and Walczak found that professors asking challenging questions resulted in more improvement in both subjective and objective measures of critical thinking.

The objective measure required that students clarify, analyze, evaluate, and extend arguments, and increased 0. The gain was much stronger in students with high pretest scores in critical thinking. There is the possibility that training working memory will in some way improve reasoning and vice versa, though most would agree at this point that the case has not yet been completely made e. A current interest of mine is to understand how fallacies in reasoning might be related to fallacies in working memory performance.

There appear to be some similarities between the two. One of the best-known reasoning fallacies is confirmation bias. Participants get that they must turn over the cards that can either confirm or disconfirm the rule in the example, the cards showing vowels. They often fail to realize that they must also turn over cards that can only disconfirm the rule. In the example, one must turn over cards with odd numbers because the rule is disconfirmed if any of those cards have a vowel on the other side.

In contrast, cards that can only confirm the rule are irrelevant. One should not turn over cards with even numbers because the rule is technically not disconfirmed no matter whether there is a consonant or vowel on the other side. Chen and Cowan in press found performance on a working memory task that closely resembles confirmation bias. In one procedure, a spatial array of letters was presented on each trial, followed by a set of all of the letters at the bottom of the screen and a single location marked; the task was to select the correct letter for the marked location.

In another procedure, the spatial array of letters was followed by a single letter from the array at the bottom of the screen and all of the locations marked; the task was to select the correct location for the presented letter.

Academic Primer Series: Eight Key Papers about Education Theory

When working memory does not happen to contain the probed item, these procedures allow the use of disconfirming information. In the first task, for example, a participant might reason as follows: The letters were K, R, Q, and L. I know the locations of only R and L and neither of them match the probed location. Therefore, I know that the answer must be K or Q and I will guess randomly between them. That would be comparable to using disconfirming evidence. The pattern of data, however, did not appear to indicate that kind of process.

Instead, participants answered correctly if they knew the probed item and otherwise guessed randomly among all of the other choices, without using the process of elimination. A mathematical model that assumed the latter process showed near-perfect convergence in capacity between the procedures described above and the usual change-detection procedure.

If we instead assumed a mathematical model of performance in which disconfirming evidence was used through the process of elimination, there was no such convergence between the procedures. So in reasoning and in working memory, processing tends to be inefficient, and it remains to be seen whether it can be meaningfully improved in terms of eliminating confirmation bias. Perhaps people with insufficient working memory or intelligence will always be stuck in such inefficient reasoning and there is nothing we can do. One might be able to train individuals to make the best use of the working memory they have without worrying about increasing the basic capacity of working memory, either by training critical thinking skills Halpern, or by instilling expertise Eriksson et al.

Working memory is the retention of a small amount of information in a readily accessible form, which facilitates planning, comprehension, reasoning, and problem-solving. When we talk of working memory, we often include not only the memory itself, but also the executive control skills that are used to manage information in working memory and the cognitive processing of information. Theoretically, there is still uncertainty about the basic limitations on working memory: While these basic issues are debated and empirical investigations continue, there is much greater agreement about what results are obtained in particular test circumstances; the results of working memory studies seem rather replicable, but small differences in method produce large differences in results, so that one cannot assume that a particular working memory finding is highly generalizable.

For learning and education, it is important to take into account the basic principles of cognitive development and cognitive psychology, adjusting the materials to the working memory capabilities of the learner. We are not yet at a point at which every task can be analyzed in advance in order to predict which tasks are doable with a particular working memory capability. It is possible, though, to monitor performance and keep in mind that failure could be due to working memory limitations, adjusting the presentation accordingly.

National Center for Biotechnology Information , U. The founders of this theory are: Vygotsky, Brunner and John Dewey , they believe that 1 knowledge is not passively received but actively built up by the cognizing subject; 2 the function of cognition is adaptive and serves the organization of the experiential world. In other words, "learning involves constructing one's own knowledge from one's own experiences. Meaning that humans generate knowledge and meaning from an interaction between their experiences and their ideas i.

Hawkins said that knowledge is actively constructed by learners through interaction with physical phenomenon and interpersonal exchanges. Mathew said that constructivist teaching and constructivist learning are Oxymoronic terms meaning that they are two terms which goes together but they are controversial to each other.

In constructivist teaching the teacher is required to enact agendas from outside the classroom that is it has to be of societal imperative but intended to enrich the curriculum at classroom level. Bell describes four forms of constructivist relationship between teacher and student these are;. This is also a traditional approach of instruction where the teacher ignores learning opportunities in the course of teaching but students are told to take note of them to be explored post learning process. This is a democratic approach of teaching where the learner is freer to explore physical environment so as to solve some problems and create new knowledge.

This is a democratic approach of teaching where learners have high opportunity in the course of learning. It was contended that, constructivist teaching scheme has five phases which are:. Helping children become aware of their prior knowledge so that teacher can know student range of ideas. Helping children become aware of an alternative point of view these goes together with modifying, replacing or extending views. The theory has far-reaching consequences for cognitive development and learning as well as for the practice of teaching in schools.

Professional development should consider the important of using learners experience in teaching and learning process. By experiencing the successful completion of challenging tasks, learners gain confidence and motivation to embark on more complex challenges Vygotsky call it as zone of proximal development ZPD Vygotsky, Teachers should encourage and accept student autonomy and initiative. They should try to use raw data and primary sources, in addition to manipulative, interactive, and physical materials. So that students are put in situations that might challenge their previous conceptions and that will create contradictions that will encourage discussion among them.

In our teaching therefore we need to use some activities which originate from our environment so that learning can be meaningful to students. So that students can construct their own meaning when learning Hawkins Ashcraft, contends that, information processing is a cognitive process which attempts to explain how the mind functions in the learning process. With this theory more emphasis is on how the information is processed than, how learning happens. The theory has three basic components which are;. This is a stage, where the learner receives the information through senses and stores it in a short tem memory.

At this point the information stays for only a fraction of a second; this is because this region is continuously bombarded by information which tends to replace the first information Shunk, The information registered at SR is then shunted to the short term memory, where its storage at this region is facilitated by process called chunking and rehearsal. Information here stays for not more than twenty seconds. If chunking and rehearsing does not occur within 20 seconds then the information will lapse. This region has an ability of storing seven plus or minus two units of information.

In order for the information to be available in a long term memory it must be transferred from short term memory to long term memory by a process called encoding. At this point the new knowledge is related to the prior knowledge stored in long term memory resulting into persistence and meaningful learning by a process called spreading activation. Mental structures called schema are involved in storage, organization and aiding of retrieval of information. Met cognition is an awareness of structures and the process involved Bigus, These are procedural knowledge and declarative.

Where it is known that procedural knowledge needs more emphasis and time than declarative knowledge. The founder of the theory is Albert Bandura who used the term social learning or observational learning to describe this theory of learning. Learning can be due to incidental social interaction and observation. Learning occurs through imitational and modeling while one observes others. The behavior of the teacher has more influence to learners because learner will imitate the behavior of the teacher regardless of whether is good or bad Omari, Learning which lead to acquiring personal emotional and satisfaction e.

Teacher must plan teaching materials which help student to develop individual skills and unlearn what is not good which was learned some time ago e. Teacher use educational learning theories in solving some psychological problem for their students like using punishment, psychology of learning help instructor in deciding the nature of learning and how to achieve it when planning for teaching and learning process. To sum up the discussion it can be said, that learning theories are of great importance to teachers in implementing their responsibilities. In Tanzania education system behaviorism and cognitivsim are the theories which are much applied by educational stakeholders this is manifested in the way teachers teach and the way assessment is conducted.

For example in assessment teachers and other examination boards set examinations aiming to measure understanding in cognitive domain leaving behind affective and psychomotor domains. Essentials of Educational Psychology: Introduction to Research in Education. Learning and Teaching; Piaget's developmental theory retrieved 19th March from http: A teacher development guide.

What is Teacher Development? Effectiveness of teachers resource centres. Dar es salaam, University of Dar es salaam. Educational psychology for teachers.

Learning Theories. Their Influence on Teaching Methods

Self-efficacy and education and instruction. Theory, research, and application. Basic principles of curriculum and instruction: University of Chicago press. The development of higher mental processes. What is a Profession? This paper may be a useful first resource to provide to junior faculty.

As an introductory resource, it compares and contrasts key theories and provides a helpful starting point to allow junior faculty to delve deeper into a theory. When encountering a question in education, it is wise to apply a conceptual framework CF. Bordage compares CF to lighthouses or lenses. A CF illuminates like a lighthouse, and magnifies certain facets of a problem. CFs, therefore, help educators better understand how to approach a problem like a lense. A CF also acknowledges any assumptions made by the investigator in answering the scholarly question. CFs can be well-established theories, models derived from theories, or evidence-based best practices.

After selecting the appropriate CF s , the scholar must rigorously apply the principles of the selected CF. Bordage presents three vignettes as examples for how to practically apply CFs in practice, thereby demonstrating a step-by-step, educationally sound approach to problems medical educators commonly face. Scholarship is the currency by which educators advance their career and the field.

Junior educators must know how to approach educational problems, design studies in education, and, more broadly, generate scholarship in education. Adequate preparation, which involves conducting a comprehensive literature review and selecting the appropriate CF s , 9 , 10 is a key step in designing scholarship. Cook describes CFs as one of six key items to report in educational experiments. Bordage asserts that scholarship in health professions education lacks the ubiquitous use of CFs.

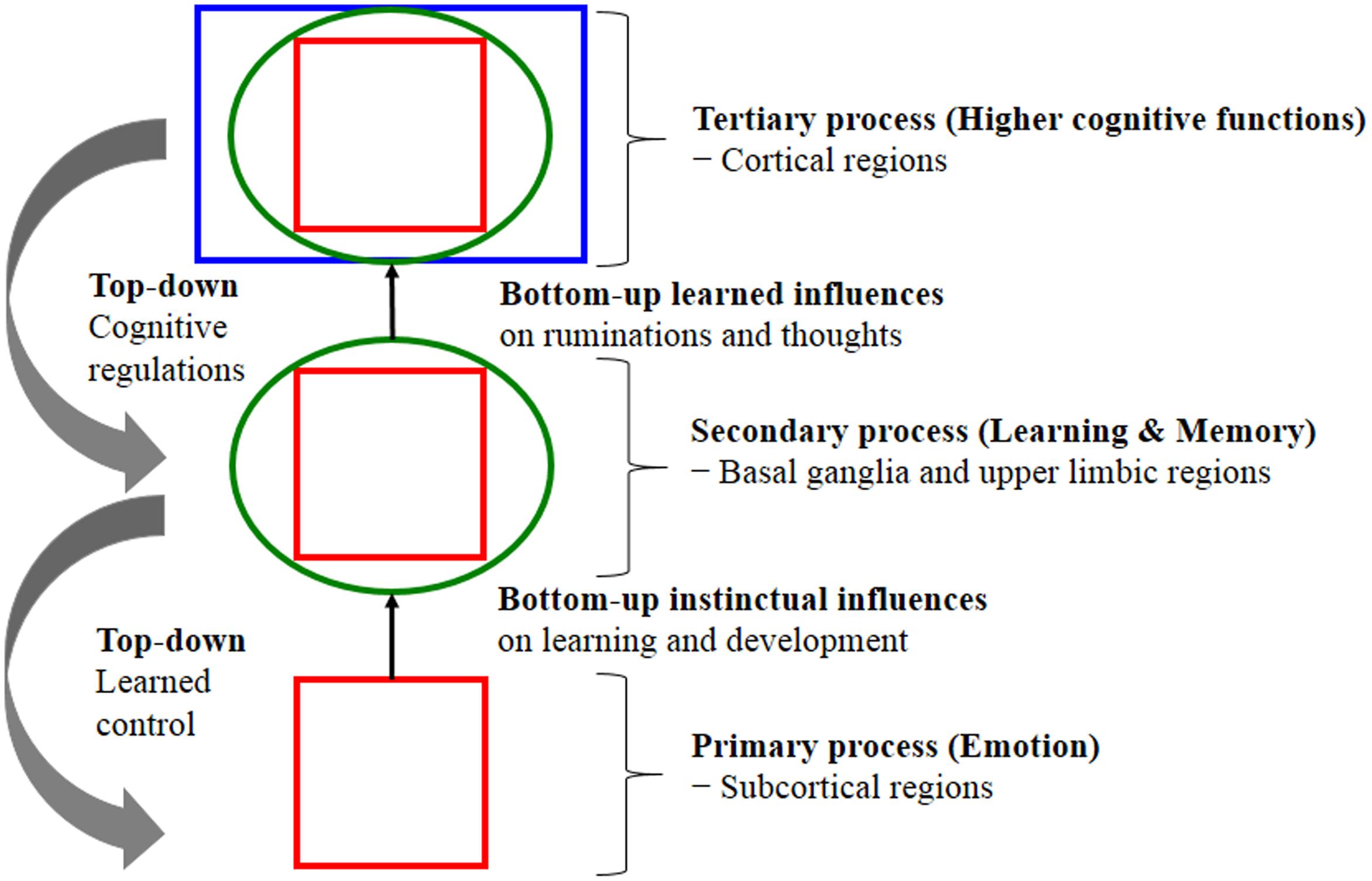

Thus, faculty developers should have an in-depth understanding of conceptual frameworks. If one considers the issue from a lens of mentorship, knowledge 14 , 15 of CFs is an essential quality of the successful mentor. This paper uses a problem-solving approach to summarize five major learning theories by applying each to the development of a new curriculum. The paper addresses most of the relevant aspects of the following learning theories: In addition to the theories defined above, social cognitive theory expands to include the role of observational learning. Learners will not solely react to stimulus; instead, they will imitate a behavior modeled by others.

Social constructivism refers to learning through the internalization and adoption of external experience. Optimal learning occurs in a zone of proximal development, where the learner needs a more expert cohort in order to advance. Teachers need to design encounters so that learners face challenges within their zone of proximal development and work together to guide each other. An expert may not be ideal if the expertise is so sophisticated that it is out of the development zone of the learner.

This paper provides a nice summary of major learning theories. It enhances the importance of consistency between the goals, objectives, instructional methods, and assessment strategies chosen for a specific learning activity or course.

Academic Primer Series: Eight Key Papers about Education Theory

While there is not one specific theory that applies to every learner, it is valuable to have multiple teaching tools available to effectively reach a spectrum of learners. This is a great primer for all faculty developers to use when looking to provide an overview paper for new educators. Many of the early career educators in the Faculty Incubator found it difficult to link theory to practice.

By providing real-life examples that link these theories to education practice, this paper is able to emphasize the importance of foundational literature. As medical educators adopt and implement a competency-based framework in medicine, the authors of this article argue that it is incumbent upon learners to drive their own education and to thoughtfully engage with their teachers and their learning environments to achieve expertise.

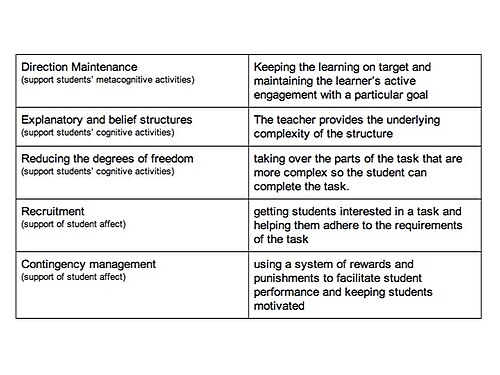

This article contains a number of examples to help junior faculty thoughtfully teach their burgeoning master learners. Through an understanding of CLT, junior educators can think through the elements of a task assigned to the learner: A motivated learner is one who feels a sense of connection. Faculty developers can cultivate this at a programmatic level by creating a collegial environment where teachers treat learners as though they are on the same team. The authors argue for cohorting trainees on the same treatment team for extended periods, beyond the typical monthly training block, to promote cohesion.

Faculty developers should be intimately aware of the state of situated cognition for their learners, exposing learners to teachers whom they admire and seek to emulate. This may include teachers who exemplify the best of evidence-based medical knowledge, superior interpersonal skills, or exceptional teamwork or leadership skills. The authors argue that program chairs should hire faculty who build individual relationships with the learners, and who effectively make tacit thought processes explicit. The work environment should include the physical space and the culture to promote teaching and feedback for learners.

This paper provides an overview of a significant number of learning theories in adult education in various contexts. The article provides an overview of theories in adult education, recognizing that adult education theory or andragogy may be foundationally flawed. Moreover, cognitive learning theorists would debate the differences in learning patterns between a child and an adult. The theory also does not consider the importance of context and social factors in acquiring knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The arrangement of these principles makes them readily accessible, connecting different concepts into a coherent framework.

Faculty developers should help junior faculty distinguish between true learning theories and seemingly reasonable ad hoc frameworks. The paper ultimately presents a framework that unifies several relevant theories in adult education. The proposed framework may be useful for faculty developers because it attempts to explain the process of learning. Using this framework, faculty developers may be able to design learning environments that promote a better transfer of knowledge, skills, and attitudes to learners in the health professions.

Cognitive psychology can be described as the study of how humans think with an intimate linkage to the study of human memory. Although educational and cognitive psychology have historically been viewed as distinct fields, the authors focus on the significant overlap between these philosophies.

This paper focuses on five key cognitive psychology concepts that influence our approach to teaching and learning: Specifically, human memory is influenced by the degree to which we can impose meaning on the stimulus, context specificity i. These cognitive psychology concepts have implications for the design of curricula and the teaching of learners. Information in isolation is of limited value. A learner who has difficulty applying knowledge may not lack understanding, but rather may need to recode the information into a clinically useful form.

Additionally, junior faculty should consider the influences on memory when teaching in the clinical environment. Teachers should emphasize clinical and bedside teaching, as well as in situ simulation. In providing variation of the learning and application environments, educators can reduce dependence on context.

At times some junior faculty members may be resistant to learning about these new concepts, so it is important for faculty developers to make clear the linkages between these key aspects of psychology and how they relate to a clinical teaching practice. In this landmark paper, Ericsson et al. The authors examine a variety of contexts in which expertise has been described, including chess, art, athletics, and typing. The authors reference a number of studies that dispel the notion that hereditary factors confer an increased likelihood of expertise in any particular domain.

They argue that the difference between an expert and a good musician is likely the result of more frequent practice and less non-music focused leisure over the many years of musical training. For further reading on this theory, we highly recommend this article to both junior faculty members and faculty developers: The fundamental tenet of this paper is that expertise is acquired rather than inherited.

It follows that any teacher can foster expertise in their learners via deliberate practice. It is important to note that not all practice is deliberate practice. Simulation facilitates the effective deployment of deliberate practice because it allows for frequent repetition not necessarily experienced in the unpredictable authentic clinical environment. Faculty developers must consider the great deal of time and effort required by deliberate practice. The individualized learning exercises must be unique to the learner and closely supervised.

For the educator teaching a large number of learners or simultaneously tending to multiple levels of learners, deliberate practice would be challenging because of the individualized attention required.