Nevertheless, the American National Academy of Sciences has written that "the evidence for evolution can be fully compatible with religious faith", a view officially endorsed by many religious denominations globally. The concepts of "science" and "religion" are a recent invention: Furthermore, the phrase "religion and science" or "science and religion" emerged in the 19th century, not before, due to the reification of both concepts. It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", "Confucianism" and "World Religions" first emerged.

It was in the 19th century that the concept of "science" received its modern shape with new titles emerging such as "biology" and "biologist", "physics" and "physicist" among other technical fields and titles; institutions and communities were founded, and unprecedented applications to and interactions with other aspects of society and culture occurred. Even in the 19th century, a treatise by Lord Kelvin and Peter Guthrie Tait's, which helped define much of modern physics, was titled Treatise on Natural Philosophy It was in the 17th century that the concept of "religion" received its modern shape despite the fact that ancient texts like the Bible, the Quran, and other sacred texts did not have a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.

Throughout classical South Asia , the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of power. The development of sciences especially natural philosophy in Western Europe during the Middle Ages , has considerable foundation in the works of the Arabs who translated Greek and Latin compositions. Christianity accepted reason within the ambit of faith.

In Christendom , reason was considered subordinate to revelation , which contained the ultimate truth and this truth could not be challenged. Even though the medieval Christian had the urge to use their reason, they had little on which to exercise it. In medieval universities, the faculty for natural philosophy and theology were separate, and discussions pertaining to theological issues were often not allowed to be undertaken by the faculty of philosophy. Natural philosophy, as taught in the arts faculties of the universities, was seen as an essential area of study in its own right and was considered necessary for almost every area of study.

It was an independent field, separated from theology, which enjoyed a good deal of intellectual freedom as long as it was restricted to the natural world. In general, there was religious support for natural science by the late Middle Ages and a recognition that it was an important element of learning. The extent to which medieval science led directly to the new philosophy of the scientific revolution remains a subject for debate, but it certainly had a significant influence. The Middle Ages laid ground for the developments that took place in science, during the Renaissance which immediately succeeded it.

With significant developments taking place in science, mathematics, medicine and philosophy, the relationship between science and religion became one of curiosity and questioning.

Science in America: Religious Belief and Public Attitudes

Renaissance humanism looked to classical Greek and Roman texts to change contemporary thought, allowing for a new mindset after the Middle Ages. Renaissance readers understood these classical texts as focusing on human decisions, actions and creations, rather than blindly following the rules set forth by the Catholic Church as "God's plan.

Renaissance humanism was an "ethical theory and practice that emphasized reason, scientific inquiry and human fulfillment in the natural world," said Abernethy. With the sheer success of science and the steady advance of rationalism , the individual scientist gained prestige. Along with the inventions of this period, especially the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg , allowed for the dissemination of the Bible in languages of the common people languages other than Latin.

This allowed more people to read and learn from the scripture, leading to the Evangelical movement. The people who spread this message, concentrated more on individual agency rather than the structures of the Church. The kinds of interactions that might arise between science and religion have been categorized by theologian, Anglican priest, and physicist John Polkinghorne: This typology is similar to ones used by theologians Ian Barbour [30] and John Haught.

According to Neil deGrasse Tyson , the central difference between the nature of science and religion is that the claims of science rely on experimental verification, while the claims of religions rely on faith, and these are irreconcilable approaches to knowing. Because of this both are incompatible as currently practiced and the debate of compatibility or incompatibility will be eternal.

Stenger 's view is that science and religion are incompatible due to conflicts between approaches of knowing and the availability of alternative plausible natural explanations for phenomena that is usually explained in religious contexts. According to Sean M. Carroll , since religion makes claims that are not compatible with science, such as supernatural events, therefore both are incompatible.

Richard Dawkins is openly hostile to fundamentalist religion because it actively debauches the scientific enterprise and education involving science. According to Dawkins, religion "subverts science and saps the intellect". According to Renny Thomas' study on Indian scientists, atheistic scientists in India called themselves atheists even while accepting that their lifestyle is very much a part of tradition and religion. Thus, they differ from Western atheists in that for them following the lifestyle of a religion is not antithetical to atheism.

Others such as Francis Collins , George F. Ellis , Kenneth R. Miller , Katharine Hayhoe , George Coyne and Simon Conway Morris argue for compatibility since they do not agree that science is incompatible with religion and vice versa. They argue that science provides many opportunities to look for and find God in nature and to reflect on their beliefs. What he finds particularly odd and unjustified is in how atheists often come to invoke scientific authority on their non-scientific philosophical conclusions like there being no point or no meaning to the universe as the only viable option when the scientific method and science never have had any way of addressing questions of meaning or God in the first place.

Furthermore, he notes that since evolution made the brain and since the brain can handle both religion and science, there is no natural incompatibility between the concepts at the biological level. Karl Giberson argues that when discussing compatibility, some scientific intellectuals often ignore the viewpoints of intellectual leaders in theology and instead argue against less informed masses, thereby, defining religion by non intellectuals and slanting the debate unjustly.

He argues that leaders in science sometimes trump older scientific baggage and that leaders in theology do the same, so once theological intellectuals are taken into account, people who represent extreme positions like Ken Ham and Eugenie Scott will become irrelevant. The conflict thesis , which holds that religion and science have been in conflict continuously throughout history, was popularized in the 19th century by John William Draper 's and Andrew Dickson White 's accounts.

It was in the 19th century that relationship between science and religion became an actual formal topic of discourse, while before this no one had pitted science against religion or vice versa, though occasional complex interactions had been expressed before the 19th century. If Galileo and the Scopes trial come to mind as examples of conflict, they were the exceptions rather than the rule. Most historians today have moved away from a conflict model, which is based mainly on two historical episodes Galileo and Darwin for a "complexity" model, because religious figures were on both sides of each dispute and there was no overall aim by any party involved to discredit religion.

An often cited example of conflict, that has been clarified by historical research in the 20th century, was the Galileo affair, whereby interpretations of the Bible were used to attack ideas by Copernicus on heliocentrism. By Galileo went to Rome to try to persuade Catholic Church authorities not to ban Copernicus' ideas. In the end, a decree of the Congregation of the Index was issued, declaring that the ideas that the Sun stood still and that the Earth moved were "false" and "altogether contrary to Holy Scripture", and suspending Copernicus's De Revolutionibus until it could be corrected.

Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy", namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the center of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves. He was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions. The Church had merely sided with the scientific consensus of the time. Only the latter was fulfilled by Galileo. Although the preface of his book claims that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher Simplicius in Latin, Simplicio in Italian , the name "Simplicio" in Italian also has the connotation of "simpleton". Most historians agree Galileo did not act out of malice and felt blindsided by the reaction to his book.

Galileo had alienated one of his biggest and most powerful supporters, the Pope, and was called to Rome to defend his writings. The actual evidences that finally proved heliocentrism came centuries after Galileo: Grayling , still believes there is competition between science and religions and point to the origin of the universe, the nature of human beings and the possibility of miracles [66].

A modern view, described by Stephen Jay Gould as " non-overlapping magisteria " NOMA , is that science and religion deal with fundamentally separate aspects of human experience and so, when each stays within its own domain, they co-exist peacefully. Stace viewed independence from the perspective of the philosophy of religion. Stace felt that science and religion, when each is viewed in its own domain, are both consistent and complete.

Science and religion are based on different aspects of human experience. In science, explanations must be based on evidence drawn from examining the natural world. Scientifically based observations or experiments that conflict with an explanation eventually must lead to modification or even abandonment of that explanation.

Religious faith, in contrast, does not depend on empirical evidence, is not necessarily modified in the face of conflicting evidence, and typically involves supernatural forces or entities. Because they are not a part of nature, supernatural entities cannot be investigated by science. In this sense, science and religion are separate and address aspects of human understanding in different ways. Attempts to put science and religion against each other create controversy where none needs to exist.

According to Archbishop John Habgood , both science and religion represent distinct ways of approaching experience and these differences are sources of debate. He views science as descriptive and religion as prescriptive. He stated that if science and mathematics concentrate on what the world ought to be , in the way that religion does, it may lead to improperly ascribing properties to the natural world as happened among the followers of Pythagoras in the sixth century B.

Habgood also stated that he believed that the reverse situation, where religion attempts to be descriptive, can also lead to inappropriately assigning properties to the natural world. A notable example is the now defunct belief in the Ptolemaic geocentric planetary model that held sway until changes in scientific and religious thinking were brought about by Galileo and proponents of his views. According to Ian Barbour , Thomas S. Kuhn asserted that science is made up of paradigms that arise from cultural traditions, which is similar to the secular perspective on religion.

Michael Polanyi asserted that it is merely a commitment to universality that protects against subjectivity and has nothing at all to do with personal detachment as found in many conceptions of the scientific method. Polanyi further asserted that all knowledge is personal and therefore the scientist must be performing a very personal if not necessarily subjective role when doing science.

Two physicists, Charles A. Coulson and Harold K. Schilling , both claimed that "the methods of science and religion have much in common. The religion and science community consists of those scholars who involve themselves with what has been called the "religion-and-science dialogue" or the "religion-and-science field.

Islamic attitudes towards science - Wikipedia

Journals addressing the relationship between science and religion include Theology and Science and Zygon. Eugenie Scott has written that the "science and religion" movement is, overall, composed mainly of theists who have a healthy respect for science and may be beneficial to the public understanding of science. She contends that the "Christian scholarship" movement is not a problem for science, but that the "Theistic science" movement, which proposes abandoning methodological materialism, does cause problems in understanding of the nature of science.

This annual series continues and has included William James , John Dewey , Carl Sagan, and many other professors from various fields. The modern dialogue between religion and science is rooted in Ian Barbour 's book Issues in Science and Religion. Philosopher Alvin Plantinga has argued that there is superficial conflict but deep concord between science and religion, and that there is deep conflict between science and naturalism.

1. What are science and religion, and how do they interrelate?

Science, Religion, and Naturalism , heavily contests the linkage of naturalism with science, as conceived by Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and like-minded thinkers; while Daniel Dennett thinks that Plantinga stretches science to an unacceptable extent. Barrett , by contrast, reviews the same book and writes that "those most needing to hear Plantinga's message may fail to give it a fair hearing for rhetorical rather than analytical reasons.

As a general view, this holds that while interactions are complex between influences of science, theology, politics, social, and economic concerns, the productive engagements between science and religion throughout history should be duly stressed as the norm. Scientific and theological perspectives often coexist peacefully. Christians and some non-Christian religions have historically integrated well with scientific ideas, as in the ancient Egyptian technological mastery applied to monotheistic ends, the flourishing of logic and mathematics under Hinduism and Buddhism , and the scientific advances made by Muslim scholars during the Ottoman empire.

Even many 19th-century Christian communities welcomed scientists who claimed that science was not at all concerned with discovering the ultimate nature of reality. Principe , the Johns Hopkins University Drew Professor of the Humanities, from a historical perspective this points out that much of the current-day clashes occur between limited extremists—both religious and scientistic fundamentalists—over a very few topics, and that the movement of ideas back and forth between scientific and theological thought has been more usual.

He also admonished that true religion must conform to the conclusions of science. Buddhism and science have been regarded as compatible by numerous authors. For example, Buddhism encourages the impartial investigation of nature an activity referred to as Dhamma-Vicaya in the Pali Canon —the principal object of study being oneself.

Buddhism and science both show a strong emphasis on causality. However, Buddhism doesn't focus on materialism. Tenzin Gyatso , the 14th Dalai Lama , maintains that empirical scientific evidence supersedes the traditional teachings of Buddhism when the two are in conflict. In his book The Universe in a Single Atom he wrote, "My confidence in venturing into science lies in my basic belief that as in science, so in Buddhism, understanding the nature of reality is pursued by means of critical investigation. Among early Christian teachers, Tertullian c. Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with Newtonian mechanics appear quite different from later attempts at reconciliation with the newer scientific ideas of evolution or relativity.

These ideas were significantly countered by later findings of universal patterns of biological cooperation. According to John Habgood , all man really knows here is that the universe seems to be a mix of good and evil , beauty and pain , and that suffering may somehow be part of the process of creation. Habgood holds that Christians should not be surprised that suffering may be used creatively by God , given their faith in the symbol of the Cross.

Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo —30 and Thomas Aquinas [97] held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on.

Modern historians of science such as J. Heilbron , [] Alistair Cameron Crombie , David Lindberg , [] Edward Grant , Thomas Goldstein, [] and Ted Davis have reviewed the popular notion that medieval Christianity was a negative influence in the development of civilization and science.

In their views, not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries. Saint Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian", not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development.

He was not unlike other medieval theologians who sought out reason in the effort to defend his faith. Lindberg states that the widespread popular belief that the Middle Ages was a time of ignorance and superstition due to the Christian church is a "caricature". According to Lindberg, while there are some portions of the classical tradition which suggest this view, these were exceptional cases.

It was common to tolerate and encourage critical thinking about the nature of the world. The relation between Christianity and science is complex and cannot be simplified to either harmony or conflict, according to Lindberg. There was no warfare between science and the church. A degree of concord between science and religion can be seen in religious belief and empirical science. The belief that God created the world and therefore humans, can lead to the view that he arranged for humans to know the world. This is underwritten by the doctrine of imago dei.

In the words of Thomas Aquinas , "Since human beings are said to be in the image of God in virtue of their having a nature that includes an intellect, such a nature is most in the image of God in virtue of being most able to imitate God". During the Enlightenment , a period "characterized by dramatic revolutions in science" and the rise of Protestant challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church via individual liberty, the authority of Christian scriptures became strongly challenged.

As science advanced, acceptance of a literal version of the Bible became "increasingly untenable" and some in that period presented ways of interpreting scripture according to its spirit on its authority and truth. In recent history, the theory of evolution has been at the center of some controversy between Christianity and science. Later that year, a similar law was passed in Mississippi, and likewise, Arkansas in In , these "anti-monkey" laws were struck down by the Supreme Court of the United States as unconstitutional, "because they established a religious doctrine violating both the First and Fourth Amendments to the Constitution.

Most scientists have rejected creation science for several reasons, including that its claims do not refer to natural causes and cannot be tested.

- Perspectives.

- Prepare, Persist & Survive (Disaster Survival Basics Book 1).

- Poppies!

- Operational Weather Forecasting (Advancing Weather and Climate Science).

- Public and Scientists’ Views on Science and Society.

- Paddle Tail (Paddle Tails Tales. Book 1)?

In , the United States Supreme Court ruled that creationism is religion , not science, and cannot be advocated in public school classrooms. Theistic evolution attempts to reconcile Christian beliefs and science by accepting the scientific understanding of the age of the Earth and the process of evolution. It includes a range of beliefs, including views described as evolutionary creationism , which accepts some findings of modern science but also upholds classical religious teachings about God and creation in Christian context.

In Reconciling Science and Religion: Bowler argues that in contrast to the conflicts between science and religion in the U. These attempts at reconciliation fell apart in the s due to increased social tensions, moves towards neo-orthodox theology and the acceptance of the modern evolutionary synthesis. While refined and clarified over the centuries, the Roman Catholic position on the relationship between science and religion is one of harmony, and has maintained the teaching of natural law as set forth by Thomas Aquinas.

For example, regarding scientific study such as that of evolution, the church's unofficial position is an example of theistic evolution , stating that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, though humans are regarded as a special creation, and that the existence of God is required to explain both monogenism and the spiritual component of human origins. Catholic schools have included all manners of scientific study in their curriculum for many centuries.

Galileo once stated "The intention of the Holy Spirit is to teach us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go. Sacred Scripture wishes simply to declare that the world was created by God, and in order to teach this truth it expresses itself in the terms of the cosmology in use at the time of the writer". According to Andrew Dickson White 's A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom from the 19th century, a biblical world view affected negatively the progress of science through time.

Dickinson also argues that immediately following the Reformation matters were even worse. The interpretations of Scripture by Luther and Calvin became as sacred to their followers as the Scripture itself. For instance, when Georg Calixtus ventured, in interpreting the Psalms, to question the accepted belief that "the waters above the heavens" were contained in a vast receptacle upheld by a solid vault, he was bitterly denounced as heretical. For instance, the claim that early Christians rejected scientific findings by the Greco-Romans is false, since the "handmaiden" view of secular studies was seen to shed light on theology.

This view was widely adapted throughout the early medieval period and afterwards by theologians such as Augustine and ultimately resulted in fostering interest in knowledge about nature through time. Modern scholars regard this claim as mistaken, as the contemporary historians of science David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Floris Cohen argued for a biblical Protestant, but not excluding Catholicism, influence on the early development of modern science.

Hooykaas ' argument that a biblical world-view holds all the necessary antidotes for the hubris of Greek rationalism: Oxford historian Peter Harrison is another who has argued that a biblical worldview was significant for the development of modern science. Harrison contends that Protestant approaches to the book of scripture had significant, if largely unintended, consequences for the interpretation of the book of nature. For many of its seventeenth-century practitioners, science was imagined to be a means of restoring a human dominion over nature that had been lost as a consequence of the Fall.

Historian and professor of religion Eugene M. Klaaren holds that "a belief in divine creation" was central to an emergence of science in seventeenth-century England. The philosopher Michael Foster has published analytical philosophy connecting Christian doctrines of creation with empiricism. Ashworth has argued against the historical notion of distinctive mind-sets and the idea of Catholic and Protestant sciences.

- Understanding Cities: Method in Urban Design.

- Islamic attitudes towards science.

- Learn To Crawl!

- Science in America: Religious Belief and Public Attitudes | Pew Research Center.

- Mother of the Year.

Jacob and Margaret C. Jacob have argued for a linkage between seventeenth century Anglican intellectual transformations and influential English scientists e. Kaiser have written theological surveys, which also cover additional interactions occurring in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Though he acknowledges that modern science emerged in a religious framework, that Christianity greatly elevated the importance of science by sanctioning and religiously legitimizing it in the medieval period, and that Christianity created a favorable social context for it to grow; he argues that direct Christian beliefs or doctrines were not primary sources of scientific pursuits by natural philosophers, nor was Christianity, in and of itself, exclusively or directly necessary in developing or practicing modern science.

Oxford University historian and theologian John Hedley Brooke wrote that "when natural philosophers referred to laws of nature, they were not glibly choosing that metaphor. Laws were the result of legislation by an intelligent deity. Numbers stated that this thesis "received a boost" from mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead 's Science and the Modern World Numbers has also argued, "Despite the manifest shortcomings of the claim that Christianity gave birth to science—most glaringly, it ignores or minimizes the contributions of ancient Greeks and medieval Muslims—it too, refuses to succumb to the death it deserves.

Protestantism had an important influence on science. According to the Merton Thesis there was a positive correlation between the rise of Puritanism and Protestant Pietism on the one hand and early experimental science on the other. Firstly, it presents a theory that science changes due to an accumulation of observations and improvement in experimental techniques and methodology ; secondly, it puts forward the argument that the popularity of science in 17th-century England and the religious demography of the Royal Society English scientists of that time were predominantly Puritans or other Protestants can be explained by a correlation between Protestantism and the scientific values.

Merton focused on English Puritanism and German Pietism as having been responsible for the development of the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries. Merton explained that the connection between religious affiliation and interest in science was the result of a significant synergy between the ascetic Protestant values and those of modern science. The historical process of Confucianism has largely been antipathic towards scientific discovery. However the religio-philosophical system itself is more neutral on the subject than such an analysis might suggest.

In his writings On Heaven, Xunzi espoused a proto-scientific world view. Likewise, during the Medieval period, Zhu Xi argued against technical investigation and specialization proposed by Chen Liang. Given the close relationship that Confucianism shares with Buddhism, many of the same arguments used to reconcile Buddhism with science also readily translate to Confucianism.

However, modern scholars have also attempted to define the relationship between science and Confucianism on Confucianism's own terms and the results have usually led to the conclusion that Confucianism and science are fundamentally compatible. In Hinduism , the dividing line between objective sciences and spiritual knowledge adhyatma vidya is a linguistic paradox.

In , English was made the primary language for teaching in higher education in India, exposing Hindu scholars to Western secular ideas; this started a renaissance regarding religious and philosophical thought. For instance, Hindu views on the development of life include a range of viewpoints in regards to evolution , creationism , and the origin of life within the traditions of Hinduism. For instance, it has been suggested that Wallace-Darwininan evolutionary thought was a part of Hindu thought centuries before modern times.

These two distinct groups argued among each other's philosophies because of their sacred texts, not the idea of evolution. Samkhya , the oldest school of Hindu philosophy prescribes a particular method to analyze knowledge. According to Samkhya, all knowledge is possible through three means of valid knowledge [] [] —.

The accounts of the emergence of life within the universe vary in description, but classically the deity called Brahma , from a Trimurti of three deities also including Vishnu and Shiva , is described as performing the act of 'creation', or more specifically of 'propagating life within the universe' with the other two deities being responsible for 'preservation' and 'destruction' of the universe respectively. Some Hindus find support for, or foreshadowing of evolutionary ideas in scriptures , namely the Vedas.

The incarnations of Vishnu Dashavatara is almost identical to the scientific explanation of the sequence of biological evolution of man and animals. As per Vedas , another explanation for the creation is based on the five elements: The Hindu religion traces its beginnings to the sacred Vedas. Everything that is established in the Hindu faith such as the gods and goddesses, doctrines, chants, spiritual insights, etc.

The Vedas offer an honor to the sun and moon, water and wind, and to the order in Nature that is universal. This naturalism is the beginning of what further becomes the connection between Hinduism and science. From an Islamic standpoint, science, the study of nature , is considered to be linked to the concept of Tawhid the Oneness of God , as are all other branches of knowledge. The Islamic view of science and nature is continuous with that of religion and God. This link implies a sacred aspect to the pursuit of scientific knowledge by Muslims, as nature itself is viewed in the Qur'an as a compilation of signs pointing to the Divine.

I constantly sought knowledge and truth, and it became my belief that for gaining access to the effulgence and closeness to God, there is no better way than that of searching for truth and knowledge. With the decline of Islamic Civilizations in the late Middle Ages and the rise of Europe, the Islamic scientific tradition shifted into a new period. Institutions that had existed for centuries in the Muslim world looked to the new scientific institutions of European powers. The Ahmadiyya movement emphasize that "there is no contradiction between Islam and science ". Over the course of several decades the movement has issued various publications in support of the scientific concepts behind the process of evolution, and frequently engages in promoting how religious scriptures, such as the Qur'an, supports the concept.

The Holy Quran directs attention towards science, time and again, rather than evoking prejudice against it. The Quran has never advised against studying science, lest the reader should become a non-believer; because it has no such fear or concern. The Holy Quran is not worried that if people will learn the laws of nature its spell will break.

The Quran has not prevented people from science, rather it states, "Say, 'Reflect on what is happening in the heavens and the earth. Jainism does not support belief in a creator deity. According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents — soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion have always existed a static universe similar to that of Epicureanism and steady state cosmological model. All the constituents and actions are governed by universal natural laws.

It is not possible to create matter out of nothing and hence the sum total of matter in the universe remains the same similar to law of conservation of mass. Similarly, the soul of each living being is unique and uncreated and has existed since beginningless time.

The Jain theory of causation holds that a cause and its effect are always identical in nature and hence a conscious and immaterial entity like God cannot create a material entity like the universe. Furthermore, according to the Jain concept of divinity, any soul who destroys its karmas and desires, achieves liberation.

A soul who destroys all its passions and desires has no desire to interfere in the working of the universe. Moral rewards and sufferings are not the work of a divine being, but a result of an innate moral order in the cosmos ; a self-regulating mechanism whereby the individual reaps the fruits of his own actions through the workings of the karmas. Through the ages, Jain philosophers have adamantly rejected and opposed the concept of creator and omnipotent God and this has resulted in Jainism being labeled as nastika darsana or atheist philosophy by the rival religious philosophies.

The theme of non-creationism and absence of omnipotent God and divine grace runs strongly in all the philosophical dimensions of Jainism, including its cosmology , karma , moksa and its moral code of conduct. Jainism asserts a religious and virtuous life is possible without the idea of a creator god. In the 17th century, founders of the Royal Society largely held conventional and orthodox religious views, and a number of them were prominent Churchmen.

Albert Einstein supported the compatibility of some interpretations of religion with science. Accordingly, a religious person is devout in the sense that he has no doubt of the significance and loftiness of those superpersonal objects and goals which neither require nor are capable of rational foundation. They exist with the same necessity and matter-of-factness as he himself. In this sense religion is the age-old endeavor of mankind to become clearly and completely conscious of these values and goals and constantly to strengthen and extend their effect.

If one conceives of religion and science according to these definitions then a conflict between them appears impossible. For science can only ascertain what is, but not what should be, and outside of its domain value judgments of all kinds remain necessary. Religion, on the other hand, deals only with evaluations of human thought and action: According to this interpretation the well-known conflicts between religion and science in the past must all be ascribed to a misapprehension of the situation which has been described.

Einstein thus expresses views of ethical non-naturalism contrasted to ethical naturalism. Prominent modern scientists who are atheists include evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and Nobel Prize—winning physicist Steven Weinberg. Between and , Laureates belonged to 28 different religions. Many studies have been conducted in the United States and have generally found that scientists are less likely to believe in God than are the rest of the population. However, in the study, scientists who had experienced limited exposure to religion tended to perceive conflict.

Religion and Science

Some of the reasons for doing so are their scientific identity wishing to expose their children to all sources of knowledge so they can make up their own minds , spousal influence, and desire for community. The survey also found younger scientists to be "substantially more likely than their older counterparts to say they believe in God". Among the surveyed fields, chemists were the most likely to say they believe in God.

Elaine Ecklund conducted a study from to involving the general US population, including rank and file scientists, in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science AAAS. Religious beliefs of US professors were examined using a nationally representative sample of more than 1, professors.

They found that in the social sciences: Out of the natural sciences: Overall, out of the whole study: He helped author a study that "found that 76 percent of doctors believe in God and 59 percent believe in some sort of afterlife. Furthermore, the term "secularism" is understood to have diverse and simultaneous meanings among Indian scientists: Over time, scientists and historians have moved away from the conflict thesis and toward compatibility theses either the integration thesis or non-overlapping magisteria. Many experts have now adopted a "complexity thesis" that combines several other models, [] further at the expense of the conflict thesis.

Global studies which have pooled data on religion and science from —, have noted that countries with high religiosity also have stronger faith in science, while less religious countries have more skepticism of the impact of science and technology. Other research cites the National Science Foundation 's finding that America has more favorable public attitudes towards science than Europe, Russia, and Japan despite differences in levels of religiosity in these cultures.

A study conducted on adolescents from Christian schools in Northern Ireland, noted a positive relationship between attitudes towards Christianity and science once attitudes towards scientism and creationism were accounted for. A study on people from Sweden concludes that though the Swedes are among the most non-religious, paranormal beliefs are prevalent among both the young and adult populations. This is likely due to a loss of confidence in institutions such as the Church and Science.

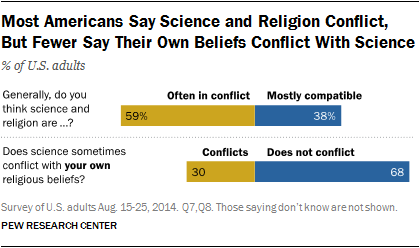

Concerning specific topics like creationism, it is not an exclusively American phenomenon. According to a Pew Research Center Study on the public perceptions on science, people's perceptions on conflict with science have more to do with their perceptions of other people's beliefs than their own personal beliefs. The MIT Survey on Science, Religion and Origins examined the views of religious people in America on origins science topics like evolution, the Big Bang, and perceptions of conflicts between science and religion. The fact that the gap between personal and official beliefs of their religions is so large suggests that part of the problem, might be defused by people learning more about their own religious doctrine and the science it endorses, thereby bridging this belief gap.

The study concluded that "mainstream religion and mainstream science are neither attacking one another nor perceiving a conflict. A study collecting data from to on the general public, with focus on evangelicals and evangelical scientists was done in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science AAAS. Other lines of research on perceptions of science among the American public conclude that most religious groups see no general epistemological conflict with science and they have no differences with nonreligious groups in the propensity of seeking out scientific knowledge, although there may be subtle epistemic or moral conflicts when scientists make counterclaims to religious tenets.

According to a poll by the Pew Forum , "while large majorities of Americans respect science and scientists, they are not always willing to accept scientific findings that squarely contradict their religious beliefs. A study from the Pew Research Center on Americans perceptions of science, showed a broad consensus that most Americans, including most religious Americans, hold scientific research and scientists themselves in high regard.

The study concluded that the majority of undergraduates in both the natural and social sciences do not see conflict between science and religion. Another finding in the study was that it is more likely for students to move away from a conflict perspective to an independence or collaboration perspective than towards a conflict view. In the US, people who had no religious affiliation were no more likely than the religious population to have New Age beliefs and practices. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. This section cites its sources but its page references ranges are too broad.

Page ranges should be limited to one or two pages when possible. You can help improve this article by introducing citations that are more precise. October Learn how and when to remove this template message. Catholic Church and evolution and Catholic Church and science.

Hindu views on evolution , List of numbers in Hindu scriptures , Hindu cosmology , Hindu units of time , Indian astronomy , Hindu calendar , Indian mathematics , and List of Indian inventions and discoveries. Science in the medieval Islamic world. Democrats are more likely than either political independents or Republicans to say there is solid evidence the earth is warming.

And, moderate or liberal Republicans are more likely to say the earth is warming than are conservative Republicans. Past Pew Research surveys have also shown more skepticism among Tea Party Republicans that the earth is warming. Consistent with past surveys , there are wide differences in views about climate change by age, with adults ages 65 and older more skeptical than younger age groups that there is solid evidence the earth is warming.

These public perceptions tend to be associated with individual views on the issue. For example, those who believe the earth is getting warmer due to human activity are most inclined to see scientists as in agreement on this point. As with perceptions of scientific consensus on other topics, public perceptions that scientists tend to agree about climate change tend to vary by education and age. College graduates are more likely than those with less formal education to say that scientists generally agree the earth is getting warmer due to human activity. Younger generations ages 18 to 49 are more likely than older ones to see scientists in agreement about climate change.

By comparison, AAAS scientists are particularly likely to express concern about world population growth and natural resources. African-Americans are more optimistic that new solutions will emerge to address the strains on natural resource caused by a growing world population. Whites and Hispanics, by comparison, are more likely to see the growing world population as leading to a major problem.

There are no differences or only modest differences in viewpoints about this issue by gender, age or education. The opposite pattern occurs in views about nuclear power. AAAS scientists show more support for nuclear power: A majority of scientists support more nuclear power plants regardless of disciplinary specialty. One newer form of energy development — increased use of genetically-engineered plants as a fuel alternative to gasoline — draws strong support among both the public and AAAS scientists.

By comparison, opinion about fracking among AAAS scientists is more negative: An earlier Pew Research analysis found that opposition to increased fracking has grown since particularly among Midwesterners, women, and those under age Men express more support than women for building nuclear power plants, more offshore drilling, and increased use of fracking.

Both men and women hold about the same views when it comes to bioengineered fuel alternatives from plants. There are no or only modest differences by education on these energy issues. A majority of Americans see the space station as a good investment for the country: Views among AAAS scientists are also broadly positive: While sending humans into space has been a prominent feature of the U.

There are only modest differences among scientists by specialty area about this issue. Men are more likely than women to say that human astronauts are essential for the future of the U. Views about this issue are roughly the same among age, education racial and ethnic groups. The Pew Research survey also asked the general public but not the AAAS scientists for their views about giving more people access to experimental drug treatments before clinical trials have shown whether such drugs are safe and effective for a specific disease or condition.

Men and women are about equally likely to favor increased access to experimental drugs before clinical trials are complete, as are those under and over age New technologies in science and medicine are generating an increasingly wide array of medical treatments. One such treatment involves creating artificial organs such as hearts or kidneys for transplant in humans needing organ replacement. Whites are more inclined than African-Americans and Hispanics to say bioengineered organs are appropriate, although majorities in each of the three groups say this is appropriate.

There are also modest differences in views about this issue by education and gender; college graduates more so than those with less education say bioengineering of organs is an appropriate use of medical advances. In addition, men more than women say bioengineered organs are an appropriate use of medical advances. The survey also asked the public about two possibilities in the realm of genetic modifications. Public views about the appropriateness of genetic therapies of this sort differ widely depending on the circumstances considered.

By comparison, fewer are negative about genetic treatment to reduce the risk of serious diseases. There are no differences, or only modest differences, in views about genetic modification in these circumstances by race, ethnicity, or education. About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world.

It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts. Patterns Among the General Public Among the general public, those with a college degree are closely divided over whether eating genetically modified foods is safe: Animal Research — Point Gap The general public is closely divided when it comes to the use of animals in research. Patterns Among the General Public Among the general public, men and women differ strongly in their views about animal research.

Food Grown with Pesticides — Point Gap A similar pattern occurs when it comes to the safety of eating foods grown with pesticides. Patterns Among the General Public As with views about the safety of eating GM foods, those with more education are more likely than those with less schooling to say that foods grown with pesticides are safe to eat. Patterns Among the General Public Perceptions of scientific consensus on both evolution and the creation of the universe tend to vary by education.

Patterns Among the General Public Younger adults are less inclined than older generations to believe vaccines should be required for all children: Climate Change — Point Gap Public attitudes about climate change have become increasingly contentious over the past several years. Views about the role of human activity in climate change have followed a similar trajectory. Patterns Among the General Public Views about climate change tend to differ by party and political ideology, as also was the case in past surveys.

Patterns Among the General Public As with perceptions of scientific consensus on other topics, public perceptions that scientists tend to agree about climate change tend to vary by education and age. Patterns Among the General Public African-Americans are more optimistic that new solutions will emerge to address the strains on natural resource caused by a growing world population. Views about the U.