But all the sources which are seen in time and nation and tradition can be traced back to the one original source, without which all these others would have sprung up in vain: No one ever felt such an inner necessity as he to communicate, sympathise and share. He owed his own education to this profound need, and the world owes its education, as far as it received it from Goethe, to this passion.

In it he formulated his deepest personal experience. This need was so rooted in his own nature that he was even obliged to turn monologue into dialogue, to transform lone thoughts into sociable conversation, as he relates in Dicktung und Wakrheit. He did this, when he was alone, by calling up in his mind someone of his acquaintance, however far away he might be. Then he developed his thought in imaginary con- versations with him. Even his writings, as he often admits, were the outcome of an urge to reveal himself, to make confession to his friends.

Goethe has said, however, that man is called to influence only the present. Writing is a misuse of language, reading in, silence and alone a sorry substitute for speech. Man exerts what influence he can on others by his personality. Again and again in private and in public Goethe acknowledged how tnuch'he owed to actual conversation, how, particularly in his scientific work, he could not have got on without exchanging thoughts and observations. This often enabled him to correct some too hasty assumption, or to progress more quickly and with less laborious investigation.

This is one case out of many in which co-operation makes for success. While Herder was writing his Ideas towards a Philosophy of the History of Mankind, Goethe held daily conversations with him which were useful to both. By this interchange of thought their intellectual resources increased daily. Goethe in particular realised through this friendship that it is interaction between the most diverse, even the most diametrically opposed, characters which achieves the greatest results. He quotes from his own experience in the introduction to the Propylaen.

Our culture dbes not advance by our merely setting in motion what lies within us and taking no trouble about it Every artist, like every man, is only a single creature and will grasp only a single aspect. That is why everyone must try, in theory and in practice, to absorb as much as he can of what is opposite to his own nature. The frivolous should seek out what is serious and earnest, the serious concentrate on something light ; the strong should cultivate gentleness and the gentle strength ; each will develop his own nature in propor- tion as he seems to depart from it.

Every art demands the whole of man, and the highest stage of art requires the whole of mankind. It is completion, then, that Goethe felt to be the issue of a relation- ship like this, and his relationship with Schiller rounded off his character. But there is another result which follows from this kind of co-operation, namely, education towards objectivity, i. Tor man as an individual is inevitably bound up in his own subjectivity, and objective truth can be reached only as his ideas gain in clarity and integrity.

This can come about through exchange of ideas, even through disagreement with others. For even disagreement postulates company, not solitude. We are so prone to mix our feelings and opinions with the facts we have learned that we do not long remain impartial observers. We are soon making observations whose validity is affected by the nature and acquired habits of our own min ds. Co-operation with others can give us greater confidence — the knowledge that we think and act not as single units but as members of a team. The fear that our mode of thought may be peculiar to us alone, which so often assails us when others express an opinion contrary to our own, is removed if we find ourselves one of a number.

It is only then that we feel confidence in these principles which we have gained from experience. When several people are associated with each other in this way and can all call each other friend, working for progressive self- education and pursuing like aims, they can be certain that how- ever devious their ways they will eventually meet. This is what Goethe found so happily true when working for the Propylaen with his Swiss friend Heinrich Meyer and Schiller. They had the liveliest exchange of thoughts on nature and art. The three friends reached such a point of mental intimacy that, although their ideas might diverse widely, no real discrepancy was possible, and their work showed only the more variety.

In the form of conversations, displaying this harmonious collaboration, Goethe publicly developed in the Propylaen his ideas on nature and art. Conversation was always a favourite literary form with Goethe, showing him to be a disciple of Plato. Even when conversation developed into controversy and sparks were struck — indeed particularly then — Goethe found it stimulating. A one-sided exposition always seemed to him a stiff and lifeless thing. Joy comes only from action and reaction. For in this case he is not content with a mere translation ; he changes it into a discussion between Diderot and himself.

And world literature is a conversation between the nations. But even where actual conversation and personal contact are impossible, letters can be exchanged and it. It requires a combined effort. Knowledge, like enclosed but running water, gradually rises to a certain level, and some of the greatest discoveries have been made not so much by individuals as by the process of time, conclusions of great importance being reached simultaneously by a number of experts.

We owe much to society and to our friends, and still more to the wide world and the age we live in. In both cases we cannot exaggerate our debt to all the instruction, help, reminders and even opposition which have set us on the right road and led us on. That is why Goethe held it necessary in the scientific field to publish every finding, even every hypothesis, and to erect the scientific edifice only when the plan for it, and its materials, were agreed on by all.

With art it is naturally rather different, and in scientific matters one has to do the opposite of what the artist finds necessary. No one can easily advise or help him. He turned them over in his own mind and as a rule no one heard anything of them until the whole was complete. In the realm of art, the stimulating co-operation of the outside world begins only when the work of art has been made public.

The echo that it sets up is of great importance to the artist. He has to consider and take to heart the blame or the praise, to incorporate it in his experience and utilise it in his future work. In a deeper sense, Goethe differentiated little between the arts and the sciences.

Neither can dispense with society. It may seem as though the poet needed no one else, and heard the promptings of the Muse most clearly when by himself. But this is self-deception. What would poets and artists be like if they had not access to the literature of all the world and did not try, in this exclusive company, to be worthy of their surroundings?

What works arc produced when the artist is not m touch with the best kind of public? The desire for approbation felt by the writei is an instinct which nature has implanted in him to call him to higher things. However small may be his aptitude for in- structing others, he longs to address himself to those who feel as he does but who are scattered all over the world. He desires to renew his contacts with his old friends and to continue them with new ones, and in the younger generation to gain others whom he will have for the rest of his life.

He wishes to spare the rising generation the bypaths among which he himself lost his way. And, while profiting by the criticisms of his contemporaries, he wishes to keep the memory of past endeavours. He had done this, and now every one of his possessions reminded him of how, and from whom, he had acquired it. He knew in each case exactly to whom he was indebted, and it was a delight to him to pay his debt of gratitude.

- Codeword Golden Fleece by Dennis Wheatley on Apple Books;

- The Fifth Essence.

- theranchhands.com: Sitemap.

- The 28th Out.

When we read his autobiographical and still more his scientific works, we constantly meet this grateful reference to spirits of the past and to living contemporaries, whatever their ages, by whom he felt he had in some way been helped. It crystallised in him the conviction that every man, even the greatest and most highly creative, is to be seen as a collective being. From his birth onwards the world begins to influence him, and so it goes on till the end. We bring faculties with us, but we owe our develop- ment to countless influences of nature, art, science and society, from which we absorb what we can and what suite our own nature.

We must all learn something from those who went before us, and from those among whom we live. Even the greatest genius would not go fhr if he aimed at being indebted to no one but himself. Originality is only an illusion. For what constitutes our real selves is not only what is ours from birth but what we are capable of acquiring. Goethe had an immense capacity for giving and for taking, a great need for intellectual companionship. If remembering this, we remember also the circumstances in which he was obliged to live, the tragedy of his existence becomes obvious.

How few were his opportunities to satisfy this most profound longing! True, he had friends and like-minded acquaintances with whom he qpuld have stimulating interchange of thought, Herder and Schiller, Graf Reinhard, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Heinrich Meyer and Zelter and others.

He could talk and exchange letters with them. But those were only isolated bright patches in his life. He was painfully aware how slow and lonely was the course of his self-culture, and how many possibilities for collaboration with his German contemporaries were closed to him. His Werther, and indeed his whole work, is understood only when one realises that the complete absence of social life in Germany forced him back upon himself and drove him to find his material in himself alone.

He explained it by the absence of any stable, unifying tradition whose natural growth he could have fostered, of any spiritual unity in the nation. There was no centre of social life and culture such as France possessed in Paris , where writers could habitually meet and help each other to achieve the way of life on which their hearts were set. Everything was , decentralised and in a state of anarchy. A Classical author of nation-wide reputation can arise, Goethe writes, only if he finds among his countrymen a compelling tradition, a spiritual agreement, and a high level of culture which enables him to develop his own powers.

But this culture did not exist, so he had no opportunity to test his own particular genius against it. German writers, born one here one there, were left very much to themselves and to the effects of widely differing backgrounds. Each had to tread his lonely way, trying to advance his own culture as best he could without help or interest from outside. He realised not only that the reason lay in the politically and socially divided state of Germany, but that this division itself was a consequence of the German national character, and that no German writer or scientist really wished it to be otherwise.

Each one of them longs to be an Original, independent of what his predecessors or contemporaries have done. He desires to follow no well-trodden path but to make his own. Each wishes to express himself alone, to speak his own language, to begin anew as if there had been nothing before him and there were nothing beside him. He calls that personal freedom, and he likes to exercise it in religion, art and science and every other sphere. No one wants to co-operate or even to admit foreign merit. Each hinders the other. And, as the German writer has no corporate society behind him, he has no desire to address himself to any public, being content if he has reached the standard he set for himself.

Goethe saw that there was one circumstance of which the nation might be justly proud, namely, that no other had pro- duced at any one time so many outstanding individuals. He agreed with the French writer Guizot that it was the Germanic people that had introduced to others the idea of personal freedom. But the Babylonian confusion that arose from the exaggeration of German individualism, the solitude and isolation of German writers which predudea the growth of any general German culture, appeared to him to be the most serious defect in the spiritual life of Germany.

And it betokened a grievous fate for one who sought. That was" an example of a naturally sociable nation whjch had created a centre for its spiritual life in its capital. Writers, authors, artists and men of learning, imbued with one spirit, had a common meeting-ground on which they could exchange their ideas and, with friendly rivalry, spur each other on to greater achievements.

He traced back the high level of general culture in France, which did not possess so many out- standing individuals, to this sociable co-operation and adherence to a common tradition. But to Goethe the loftiest exemplar was always Ancient Greece, in which the highest pitch of general national culture was combined with an abundance of great men. The constant and unified character of their literature and art was no handicap to genius. He believed he was doing his people the greatest service m showing, as he did in his autobiographical work, Dichtung und Wahrheit , how each successive age in Germany had tried to suppress and supplant its predecessor, instead of being thankful to it for what it had taught them.

He went on to actual example, by seeking to create in the Weimar circle a model of German social life centering in himself. In the history of German literature there had of course been previous attempts to form such circles, and Goethe pays tribute to them in his diaries and year books. He admitted that the better part of the nation had realised by the 1 8 th century that this state of things could not be continued.

Many people were then moved by the same impulse. So the large group split up into smaller, mostly local, ones which did achieve something, but the intellectuals tended to become still more isolated. Literary circles were formed, without lactual personal contacts, merely on the strength of a common object of veneration, such as Klopstock or Wieland, for example.

But they lacked, as we said, any real unity, and they rather exaggerated than cured the state of isolation. Now Weimar was to be the nucleus of a German spiritual community, a centre whose circumference, limited at first, was to extend farther and farther. We have a false picture of Weimar if we do not see that here a fully conscious organising spirit was at work, creating a pattern for German social life.

But the Weimar writers soon went beyond their own small group and tried to form a wider circle , in fact to draw all German artists and the whole German public into their com- munity. It was stipulated that they should all deal with the same subject, prob- ably from Greek Mythology, so that the scattered artists should unite in friendly rivalry, and lose the feeling of isolation. A prize was also offered for the best comedy. Schiller sought out the best brains in Germany to contribute to the successive numbers of the Horen, describing himself as merely the mouthpiece of the group which had come together to publish the journal.

The articles in it, which often took the form of conversations, were reflections on nature, art and science, contributed as the result of an exchange of ideas between kindred spirits. In later years, whenever Goethe saw similar circles being formed with scientific or artistic aims, such as the Friends of Art in Frankfurt or other groups anywhere he got into touch with them and began an exchange of ideas. He wrote on one occasion to a society in Batavia: Goethe in his later years made contact not only with German but also with European and even extra-European societies interested in art and science.

He hoped gradually to affiliate German literature, creative as well as scientific, with the other literatures of Europe and of the worlcf. In this way his efforts at unification, begun in and for Weimar, merge in his idea of world literature. In the last decade of his life, in , Goethe was able to tell a foreign guest that he belonged to a society equal to the best in any great city.

Not long before his death, in , Goethe drew up a memorandum for the inauguration of the circulating library in Weimar. I From amongst a more or less crude mass, narrow circles of cultured people are formed ; they are on the most intimate terms ; a man entrusts his thoughts only to a friend, sings his song only to the loved ones ; an atmosphere of domesticity prevails. The circles are closed to outsiders as a protection from the harsher aspects of life. IV To reach the universal stage requires goodwill and good fortune, and today we may pride ourselves on enjoying both.

For, though for many years we have faithfully fostered these successive stages, something more was needed to accomplish what we see now. This is no less than the uniting of all cuFtflred circles which up to now had merely touched, the recognition of one single aim, the realisation of how needful it is to become aware of contemporary affans, and familiar with the trend of thought in the world we live in.

Foreign literatures are all on an equal footing with our own, and wc play our part in the world circulation of ideas. Goethe here sketches and represents as an organic growth the whole progress which he had himself initiated and led. The Weimar circle of a few like-minded men with a common aim had developed into a partnership embracing the whole of Europe. The literary collaboration of the men of Weimar had become a collective European literature. The harmony which such dia- metrically opposed thinkers as Goethe and Schiller had reached by reciprocal assistance Jhad become the harmonious completion of France by Germany, of Germany by France.

Writers of every nation acknowledged their debt to Goethe, honoured him as their intellectual father, the leader of the intellectual life of Europe, and Weimar was the spot to which not only the writings of European authors came, but to which they themselves made pilgrimage. The little world- system, the microcosmos Weimar, had grown to a great world- system, a macrocosmos, in which the planets of the intellectual universe revolved round the fixed star, Goethe. The idea evolved from his realisation that a world literature was in actual fact taking shape in his own time.

It was only a new name for an actual histoiical process which Goethe was witnessing, and which presaged the dawning of a new literary age. For Goethe nothing had real existence unless he had himself experienced it. Therefore his idea of world literature developed out of his own feeling of in- debtedness to foreign literatures. The culture he had imbibed from them had helped to make him what he was, a power in the literary world of Europe.

The rising generation in Europe hailed him as its leader and spiritual head. This experience indicated to Goethe that German literature was now no longer merely receptive, modelling itself on others which despised and neglected it. It now had something to contribute ; it played an active part in the development of European literatures, and in particular had a rejuvenating effect on the jaded spiritual life of Europe. So, when Goethe speaks of world literature as something that is taking shape, we must ask the question whether it was really only beginning to develop in his time.

In the Middle Ages and the Age of Humanism there existed a universal language, Latin, in which not only could the learned men of every nation exchange their thoughts but in which also an extra-national poetry grew up. For, in the first place, the circle which inew and used it was limited to scholars, and in the second place world literature ought to be not a colour- less unity but a" lively conversation. When he developed his idea of world literature in conversation with Eckermann, and spoke HISTORY 53 of the need for acquainting oneself as he did with foreign literatures, he added that, however much one admired them, none could serve as a pattern.

If we look for a model we must turn to the ancient Greeks, in whose works the perfection of human endeavour was represented. We must look at everything else from the historical point of view, appropriating, as far as we can, what is good in it. But Goethe certainly did not recognise as world literature merely any literature written in one universal language.

If we take German literature in particular, it has always been open to literary influences from abroad, has modelled itself on them, interested itself critically in them, and developed a vast activity in the work of translation. Through every age, German literature shows a tendency to look to the Romance literatures for guidance in form and proportion, purity and beauty.

Middle High German literature took its formal and social education from France. French literature was used in the 16th century to help to overcome German crudity in art and society. Even the Baroque movement, consciously national in its ambition to raise German literature to the level of other European literatures, employed translation and imitation to show that what was possible in other languages was possible also in German.

German classicism, superseding the Baroque style, copied the example of the French from whom it learned to endow German poetry with symmetry, clarity, good taste and reasonableness. There was no cause to complain of spiritual autarchy ; the -danger was rather that German literature, from sheer excessive open-heartedness. No country has ever been so appreciative of others as you. Do not be over- appreciative. A universal human harmony would be achieved only by uniting the voices of the nations in one great choral song. The German Romantic movement largely realised this idea through trans- lations taken from all the literatures of the world.

Goethe him- self repeatedly drew attention to the vast amount of translation in German literature which had been of mutual benefit. Why then did Goethe identify the beginning of world literature with his own age, and characterise it as something only now taking shape and drawing near?

He did so from the point of view of German literature. No world literature is, possible without exchange. But what had been the case up to now? German literature had undoubtedly preserved an open attitude to foreign influence and had always shown an interest in other literatures. But was the opposite true?

Had the literatures of Europe concerned themselves likewise with German literature? Had they translated from it, learned from it, and judged it fairly? They had indeed judged it, but without real knowledge and care, and above all without goodwill, and their judgment was therefore merely condemnation and contempt. German litera- ture was called barbaric, uncouth, harsh, ugly, Hyperborean.

You can almost count on your fingers the translations from German literature up to the 18th century. The German works which did penetrate to other countries were, for the most part, not strictly speaking works of literature but religious, mystical and philosophical writings. The great philosopher Nicolas of Cusa certainly had an important influence on the Italian Renais- sance, partly because he lived and worked in Italy. On March the 8th, , Giordano Bruno delivered a farewell speech in Wittenberg where, after banishment, persecution and fear of death, he had found a welcome and freedom to continue his studies.

This was certainly a rhetorical flight of fancy, but it is true that the eyes of every land were directed to Luther, and the writings of Paracelsus and of Agrippa of Nettesheim were read everywhere. Some few works of imaginative literature, too, crossed the borders of Germany. Till Eulenspiegel, too, and other German popular figures, became naturalised in the literatures of Europe. At the beginning of the period of modern German, it really seemed as though its literature had a part to play in the world, and it is of great interest to reconstruct the concept that the world then had of the German spirit and to note the influence which it exerted.

For it is practically the same concept and the same influence as we find in the 19th-century phase of Romanticism in Europe. There are, in other words, some constant factors in world literature. Even then it was German popular poetry in the form of chapbooks and popular ballads that the other countries absorbed. It was the Faustian spirit of Nicolas of Cusa that made the idea of the infinity of space and time and the human spirit a European idea.

It was the message of individual freedom that Luther brought. But it all halted at r the first stage. It was a prelude to the world-wide significance of German literature, which was to take centuries to reach fulfilment. There was a reason for this. It was a real tragedy. The more German literature struggled by means of imitation to achieve significance, the farther it went astray.

Even its efforts passed unnoticed or were regarded as bar- barous eccentricities. This came to an end in the ifilh century, when the nations, filled with the idea of one universal humanity, began to look beyond their frontiers and to attempt just criticism. But although Gottsched, Wieland, Gellert and other German writers now found acknowledgment and acceptance in French literature, we must remember that this happened only because these writers were themselves the product of the French school, and France was merely getting back what she had given.

Ger- man literature had as yet nothing of its own to bestow. Even Lessing could hardly give anything to France which Diderot had not already expressed. In the first place there were the new journals which appeared in the course of the 18th century. The second half of the 17 th century had of course its journals, such as the Journal des Savants from , the Nouvelles de la RSpublique des Leilres from 1C84 , the Bibliotheque Universelle from They adopted a universal European tone and dealt with the German point of view, but their main concern was with scientific literature.

Imaginative literature came only exceptionally within their purview. These journals were supra- national in their desire to found a republic of the sciences. The 1 8th century, on the other hand, witnessed the founding of the BibliothSque Anglaise , the BibliothSque Germanique , the BibliolMque Italique , and these were conscious attempts to familiarise the nations of Europe, whose interests so far had been restricted to French literature, with English, German and Italian literature.

While each of these journals had its specialised sphere of activity, the Bulletins littSraires of Fr. Melchior Grimm, the Journal Stranger and the Journal litteraire from and many other journals in France had real influence in the direction of world literature. Every nation, the Journal goes on to say, will be enriched by the treasures of its rivals without losing any of HISTORY 57 its own, and so the whole of Europe will become better educated, more philosophical ; and the Journal etranger hopes to have the good fortune to help in this task.

🏷️ Ebooks For Mobile Diener Der Finsternis Duke De Richleau German Edition By Dennis Wheatley Pdf

Many voices were saying much the same thing. French literature is very widely known in Germany, and journals publish reports of all our doings. There is also much just criticism. Soon, too, contributors began to mention their hopes for the wholesome and rejuvenating influence which German literature might have on French. This is particularly noticeable after France had become aware of Albrecht von Haller, Salomon Gessnei; and certain German writers who carried on their traditions. Tacitus, in his Germania , had contrasted the simple moral and religious life among the German peoples with an over-civilised and decadent Rome.

denniswheatley photos - theranchhands.com

In the same way the idyllic poetry of a Haller or Gessner is contrasted as the ideal image of return to nature, to simplicity, to morality and religion. The Swiss and German writers make their entry into French literature with Rousseau. In the seventies and eighties the works of the younger German dramatists became known in France through the Thidtre Allemand , edited in by Junker and Liebault, and the Nouveau Theatre Allemand by Friedel and Bonne- ville There is no doubt that this paved the way for the tremendous influence of Werther , which swept across France.

There were, how- ever, important obstacles to be overcome. The opposition which German literature found in other countries was far greater than that found by any other literature among the civilised nations of Europe. There is a Reason for this, and it lies in the very nature of the German spirit. It is indeed a staggering thought that even today writers like Holder- lin and Klcist have not yet succeeded in gaining a woxihy place in world literature, while French writers of infinitely lower rank aie quite well known in Europe. Has the German language ever become a universal language, as the French did?

The universal language of Germany, known and loved everywhere, has been up to the present day not its poetry but its music. What then delayed the acceptance of German literature as work of world importance? Just as, however, the military strength of a nation grows out of its inner unity, so aesthetic strength is the gradual outcome of a similar unanimity.

But this is possible only with the passage of time. I can look back over so many yeais as one of the collaborators, and I can see how German literature has been composed of heterogeneous, not to say waning, elements. It is really one literatuie only in the sense that it is written in one language. How much more fortunate was France in this respect. Men of the type who contribute to the Globe [the organ of the French Romantic movement J, men gi owing greater and more im- portant from day to day and all filled with one spa it— [Goethe said on one occasion to Eckextnann] are quite unimaginable m Germany, where such a periodical would be a sheer impossibility.

So Germany was accepted by the world only slowly and gradually. And yet, is this delect not merely the consequence of the German idea of the individual and his personal freedom? In noting this, she points not only to a tragic fate but also to a high ideal, and to the most fundamental quality in German poetry. But how can this idea of a free, creative, detached individual form any union between the peoples?

In the French journal Le Globe there appeared this explanation for the fact that so little was known in France of what Goethe had written after Werther: What is m a high degreg original, that is to say deeply impressed with the character of a particular man or nation, is rarely appreciated at once , and originality is the most prominent virtue of this writer. Indeed, one might go so far as to say that in his independence he carries this quality, without which genius does not exist, to excess. Every other writer follows a consistent and easily recognisable course ; but he is so different from the others and often from himself, one can so seldom guess his drift, he so diverts the usual course of criticism, even of admiration, that to enjoy his works one must have as few literary prejudices as he has ; and no doubt it would be as hard to find a reader quite devoid of these as to find a writer who rises above them all as he does.

So it is not suprismg that he is not popular m France. One could hardly characterise German literature more aptly than by saying that it has never created any form, such as for instance the classical ode, the romantic sonnet, or the eastern ghazal. When German poetry requires forms like these, binding and detached from personality, it must borrow them from other literatures. German poetry, when left to itself without imitation of foreign literatures, has never subscribed to the ideal of perfect beauty, so common elsewhere. For German poetry has always been essentially expressive, aiming at truth rather than at beauty, however hard and painful and intolerable that truth might be.

And you too, my friend, would have all you could wish for ; the thirsty man sees not the proffered bowl but the fruits it contains. The German God is no common deity shared by all, and accepted as a traditional possession. The German is a seeker after God. Dante leads one through a world-system of hell, purgatory and paradise. But Parzival seeks his god along lonely untrodden ways. He reached his goal only because a sort of instinct guided him and he kept faith with himself.

When we remember that it was with the Faust-spirit in the widest sense of the word that German poetry was destined to inspire other literatures, we shall better under- stand the prolonged opposition which that spirit had to over- come. It is a spirit of longing, never satisfied even in the moment of delight, never content at any stage, unappeased by any happi- ness, seeking and striving beyond any passing moment, always HISTORY 6l suffering in contact with the world, always unsatisfied because always fired by the vision of a distant and barely divined goal.

The way matters more than the aim, the search more than the finding. Every form is irksome and must be broken ; every limitation intolerable and must be ignored. The Pan-German Vision T H EAustrian state in which both List and Lanz came of age and first formulated their ideas was the product of three major political changes at the end of the s. These changes consisted in the exclusion of Austria from the German Confederation, the administrative separation of Hungary from Austria, and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in the 'Austrian' or western half of the empire.

The constitutional changes of ended absolutism and introduced representative government and fulfilled the demands of the classical liberals, and the emperor henceforth shared his power with a bicameral legislature, elected by a restricted four-class franchise under which about 6 per cent of the population voted. Because liberalism encouraged free thought and a questioning attitude towards institutions, the democratic thesis of liberalism increasinglychallenged its early oligarchic form. A measure of its appeal is seen in the decline of the parliamentary strength of parties committed to traditional liberalism and the rise of parties dedicated to radical democracy and nationalism, a tendency that was reinforced by the widening of the franchise with a fifth voter class in This development certainly favoured the emergence of Pan-Germanism as an extremist parliamentary force.

The other political changes in Austria concerned its territorial and ethnic composition. Separated from both Germany and Hungary, the lands of the Austrian half of the empire formed a crescent-shaped territory extending from Dalmatia on the Adriatic coast through the hereditary Habsburg lands of Carniola, Carinthia, Styria, Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia to the eastern provinces of Galicia and Bukovina. The somewhat incongruous geographical arrangement of this territory was compounded by the settlement of ten different nationalities within its frontiers.

Nationality in Austria was defined by. Most of the Germansabout 10 million in lived in the western provinces of the state and constituted about 35 per cent of its 28 million inhabitants. In addition to Germans, Austria contained 6,, Czechs 23 per cent of the total population , 5,, Poles 18 per cent , 3,, Ruthenes or Ukrainians 13 per cent , 1,, Slovenes 5 per cent , , Serbo-Croats 3per cent , , Italians 3 per cent , and and , Romanians 1 per cent. The population and nationality figures for the provinces of the state indicate more dramatically the complexity ofethnic relationships: Against the background of democratization, some Austrian Germans began to fear that the supremacy of German language and culture in the empire, a legacy of rationalization procedures dating from the late eighteenth century, would be challenged by the nonGerman nationalities of the state.

This conflict of loyalties between German nationality and Austrian citizenship, often locally sharpened by anxieties about Slav or Latin submergence, led to the emergence of two distinct, although practically related, currents of German nationalism. Ih'lkisch-culturalnationalism concerned itselfwith raising national consciousness among Germans, especially in the large conurbations and provinces of mixed nationality, through the foundation of educational and defence leagues Vereine to foster German culture and identity within the empire.

Pan-Germanism was more overtly political, concerned with transforming the political context, rather than defending German interests. It began as the creed of the small minority of Germans in Austria who refused to accept as permanent their separation from the rest of Germany after , and who determined to repair this breach of German unity by the only means possible after Bismarck's definitive military victory over France in By a considerable number of volkisch-cultural Vereine were operating in the provinces and Vienna.

They occupied themselves with the discussion and commemoration of figures and events in German history, literature and mythology, while investing such communal activities as choral singing, gymnastics, sport and mountainclimbing with volkisch ritual. In a federation of these Vereine, the Germanenbund, was founded at Salzburg by Anton Langgassner. Member Vereine of the federation held Germanic festivals, instituted a Germanic calendar, and appealed to all classes to unite in a common Germanic Volkstum nationhood. Their chief social bases lay in the provincial intelligentsia and youth.

The government regarded such nationalism with wariness and actually had the Germanenbund dissolved in ; it was later re-founded in as the Bund der Germanen. During the s and s he wrote for the journals of the movement; he attended the Verein 'Deutsche Geschichte', the Deutscher Turnverein and the rowing club Donauhort at Vienna, and the Verein 'Deutsches Haus' at Brno; and he was actively involved in the festivals of the Bund der Germanen in the s.

It is against this ongoing mission of the volkisch-cultural Vereine in the latter decades of the century that one may understand the inspiration and appeal of his nationalist novels and plays in the pre-occult phase of his literary output between and The Pan-German movement originated as an expression of youthful ideals among the student fraternities of Vienna, Graz, and Prague during the s. Initially formed in the s, these Austrian fraternities were modelled on the German Burschenschaften student clubs of the Vormarz period the conservative era between 18 15 and the bourgeois liberal revolution of March ,which had developed a tradition of radical nationalism, romantic ritual and secrecy, while drawing inspiration from the teachings of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn , thevolkisch prophet ofathleticism, German identity, and.

Certain fraternities, agitated by the problem of German nationality in the Austrian state after , began to advocate kleindeutsch nationalism; that is, incorporation of German-Austria into the German Reich. They glorified Bismarck, praised the Prussian army and Kaiser Wilhelm I, wore blue cornflowers supposed to be Bismarck's favourite flower and sang 'Die Wacht a m Rhein'at their mass meetings and banquets.

This cult of Prussophilia led to a worship of force and a contempt for humanitarian law and justice. Georg von Schonerer I first associated himself with this movement when he joined a federation of kleindeutsch fraternities in atVienna. His ideas, his temperament, and his talent as an agitator, shaped the character and destiny of Austrian Pan-Germanism, thereby creating a revolutionary movement that embraced populist anti-capitalism, anti-liberalism, anti-Semitism and prussophile German nationalism.

Having first secured election to the Reichsrat in , Schonerer pursued a radical democratic line in parliament in common with other progressives of the Left until about By then he had begun to demand the economic and political union of German-Austria with the German Reich, and from he published a virulently nationalist newspaper, Unvefalschte Deutsche Worte [Unadulterated German Words], to proclaim his views. The essence of Schonererite Pan-Germanism was not its demand for national unity, political democracy, and social reform aspects of its programme which it shared with the conventional radical nationalists in parliament , but its racism-that is, the idea that blood was the sole criterion of all civic rights.

The Pan-German movement had become a minor force in Austrian politics in the mid-1 s but then languished after the conviction of Schonerer in for assault; deprived of his political rights for five years, he was effectively removed from parliamentary activity. Not until the late s did Pan-Germanism again attain the status of a popular movement in response to several overt challenges to German interests within the empire. It was a shock for those who took German cultural predominance for granted when the government ruled in that Slovene classes should be introduced in the exclusively German school at Celje in Carniola.

This minor controversy assumed a symbolical significance among German nationalists out of all proportion to its local implications. Then in April the Austrian premier, Count Casimir Badeni, introduced his controversial language. These decrees provoked a nationalist furore throughout the empire. The democratic German parties and the Pan-Germans, unable to force the government to cancel the language legislation, obstructed all parliamentary business, a practice which continued until When successive premiers resorted to rule by decree, the disorder overflowed from parliament onto the streets of the major cities.

During the summer of bloody conflicts between rioting mobs and the police and even the army threatened to plunge the country into civil war. Hundreds of German Vereine were dissolved by the police as a threat to public order. Not all Pan-German voters expressly wanted the economic and political union of German-Austria with the German Reich as proposed by Schonerefs programme.

Their reasons for supporting the party often amounted to little more than the electoral expression of a desire to bolster German national interests within the empire, in common with the myriad vijlkisch-cultural Vereine. For wherever they looked in the course of the past decade, Austrian Germans could perceive a steadily mounting Slav challenge to the traditional predominance of German cultural and political interests: Many Austrian Germans regarded this political challenge as an insult to their major owning, tax-paying and investment role in the economy and the theme of the German Besitzstand property-owningclass in the empire was generally current at the turn of the century.

Lanz's early Ostara issues and other articles addressed themselves to the problems of universal suffrage and the German Besitzstand. Both List and Lanz condemned all parliamentary politics and called for the subjection of all the nationalities in the empire to German rule.

iTunes is the world's easiest way to organize and add to your digital media collection.

Ariosophy were clearly related to this late nineteenth-century GermanSlav conflict in Austria. The strident anti-Catholicism of Ariosophy may also be traced to the influence of the Pan-German movement. The episcopate advised the emperor, the parish priests formed a network of effective propagandists in the country, and the Christian Social party had deprived him ofhis earlier strongholds among the rural and semi-urban populations of Lower Austria and Vienna. He thourht that a Protestant conversion moveu ment could help to emphasize in the mind of the German public the association of Slavdom-after hated and feared by millionswith Catholicism.

The conservativeclerical-slavophile governments since had indeed made the emergence of a populistic and anti-Catholic German reaction plausible and perhaps inevitable. Many Germans thought that the Catholic hierarchy was anti-German, and in Bohemia there was resentment at the number of Czech priests who had been given German parishes. In order to exploit these feelings, Schonerer launched his Los uon Rom break with Rome campaign in The alliance remained uneasy: For their part, the missionary pastors complained that the political implications of conversion alienated many religious people who sought a new form of Christian faith, while those who were politically motivated did not really care about religion.

The rate of annual conversions began to decline in , and by had returned to the figure at which it had stood before the movement began. Although a movement of the ethnic borderlands, its social bases were principally defined by the professional and commercial middle classes. The greatest success of the Los uon Rom movement therefore coincided chronologically and geographically with the prestige of the Pan-German party: Although the Los vom Rom movement was a political failure, it highlights the anti-Catholic sentiment that among many Austrian Germans during the s. This mood was an essential element of Ariosophy.

List cast the Catholic Church in the role of principal antagonist in his account of the Armanist dispensation in the mythological Germanic past. He abandoned his Cistercian novitiate in a profoundly anti-Catholic mood in , joined the Pan-German movement, and is said to have converted briefly to Protestantism. Racism was a vital element in the Ariosophists' account of national conflict and the virtue of the Germans. An early classic on the superiority of the Nordic-Aryan race and a pessimistic prediction of its submergence by non-Aryan peoples was Arthur de Gobineau's essay.

When the Social Darwinists invoked the inevitability of biological struggle in human life, it was proposed that the Aryans or reallv the Germans need not succumb to the fate ofdeterioration. This shrill imperative to crude struggle between the races and eueenic reform found broad acceptance in " Germany around the turn of the century: I3 These scientific formulations of racism in the context of physical anthropology and zoology lent conviction to volkisch nationalist prejudice in both Germany and Austria. List borrowed stock racist. The central importance of 'Aryan' racism in Ariosophy, albeit compounded by occult notions deriving from theosophy, may be traced to the racial concerns of Social Darwinism in Germany.

If some aspects of Ariosophy can be related to the problems of German nationalism in the multi-national Habsburg empire at the end of the nineteenth century, others have a more local source in Vienna. Unlike the ethnic borderlands, Vienna was traditionally a German city, the commercial and cultural centre of the Austrian state.

However, by , rapid urbanization of its environs, coupled with the immigration of non-German peoples, was transforming its physical appearance and, in some central districts, its ethnic composition. Old photographs bear an eloquent testimony to the rapid transformation of the traditional face of Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century.

During the s the old star-shaped glacis of Prince Eugene was demolished to make way for the new Ringstrasse, with its splendid newpalazs and public buildings. A comparison of views before and after the development indicates the loss of the intimate, aesthetic atmosphere of a royal residence amid spacious parkland in favour of a brash and monumental metropolitanism. It may be that List rejected urban culture and celebrated rural-medieval idylls as a reaction to the new Vienna.

Between and the population of the city had increased nearly threefold, resulting in a severe housing shortage. By no less than 43 per cent of the population were living in dwellings of two rooms or less, while homelessness and destitution were widespread.

In only some 6,Jews had resided in the capital, but by this number had risen to ,, which was more than 8 per cent of the total city population; in certain districts they accounted for 20 per cent of the local residents. Germans with volkisch attitudes would have certainly regarded this new influx as a serious threat to the ethnic character of the capital. An example of this reaction is found in Hitler's description of his first encounter with such Jews in the Inner City. I6 Given the Ariosophists' preoccupation. It remains to be asked if Ariosophy's assimilation of occult notions deriving from theosophy also had a local source in Vienna.

Although a Theosophical Society had been established there in , no German translation of the movement's basic text, The Secret Doctrine, was published until The s subsequently witnessed a wave of German theosophical publishing. But while the date of the ariosophical texts from onwards relates to the contemporary vogue of the theosophical movement in Central Europe, it is not easy to ascribe a specifically Austrian quality to the volkisch-theosophical phenomenon.

Mystical and religious speculations also jostled with quasi-scientific forms e. Social Darwinism, Monism of volkisch ideology in Germany. It is furthermore significant that several important ariosophical writers and many List Society supporters lived outside Austria.! Given the large number ofvolkisch leagues in Vienna, it is not so remarkable that a small coterie should have exploited the materials of a new sectarian doctrine as fresh 'proof' for their theories of Aryan-German superiority.

The particular appropriateness of theosophy for a vindication of elitism and racism is reserved for a later discussion. I s To conclude: Although still outwardly brilliant and prosperous, Vienna had become embedded in the past. In the modernizing process, that 'old, cosmopolitan, feudal and peasant Europe'-which had anachronistically survived in the territory of the empire-was swiftly disappearing.

Some bourgeois and petty bourgeois in particular felt threatened by progress, by the abnormal growth of the cities, and by economic concentration. These anxieties were compounded by the increasingly bitter quarrels among the nations of the empire which were, in their turn, eroding the precarious balance of the multi-national state.

Such fears gave rise to defensive ideologies, offered by their advocates as panaceas for a threatened world. That some individuals sought a sense of status and security in doctrines of German identity and racial virtue may be seen as reaction to the medley of nationalities at the heart of the empire. Writing of his Widenuiihg war mir das Rassenkonglomerat, das die Reichshauptstadt zeigte, widerwartig dieses ganze Irdkergemisch von Tschechen, Polen, Ungarn, Ruthaen, Serben und Kroaten.

Mir erschien die Riesenstadt als die Viko'pemng der Blutschande. The city seemed the very embodiment of racial infamy. It is a tragic paradox that the colourful variety of peoples in the Habsburg empire, a direct legacy of its dynastic supra-national past, should have nurtured the germination of genocidal racist doctrines in a new age of nationalism and social change. Its principal ingredients have been identified as Gnosticism, the Hermetic treatises on alchemy and magic, NeoPlatonism, and the Cabbala, all originating in the eastern Mediterranean area during the first few centuries AD.

Gnosticism properly refers to the beliefs of certain heretical sects among the early Christians that claimed to posses gnosis, or special esoteric knowledge of spiritual matters. Although their various doctrines differed in many respects, two common Gnostic themes exist: The Gnostic sects disappeared in the fourth century, but their ideas inspired the dualistic Manichaean religion of the second century and also the Hermetica. These Greek texts were composed in Egypt between the third and fifth centuries and developed a synthesis of Gnostic ideas, Neoplatonism and cabbalistic theosophy.

Since these mystical doctrines arose against a background of cultural and social change, a correlation has been noted between the proliferation of the sects and the breakdown of the stable agricultural order of the late Roman Empire. Prominent humanists and scholar magicians edited the old classical texts during the Renaissance and thus created a modern corpus of occult speculation. But after the triumph ofempiricism in the seventeenth-century. By the eighteenth century these unorthodox religious and philosophical concerns were well defined as 'occult', inasmuch as they lay on the outermost fringe of accepted forms of knowledge and discourse.

Codeword Golden Fleece

However, a reaction to the rationalist Enlightenment, taking the form of a quickening romantic temper, an interest in the Middle Ages and a desire for mystery, encouraged a revival of occultism in Europe from about Germany boasted several renowned scholar magicians in the Renaissance, and a number of secret societies devoted to Rosicrucianism, theosophy, and alchemy also flourished there from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.

However, the impetus for the neo-romantic occult revival of the nineteenth century did not arise in Germany. It is attributable rather to the reaction against the reign of materialist, rationalist and positivist ideas in the utilitarian and industrial cultures of America and England. The modern German occult revival owes its inception to the popularity of theosophy in the Anglo-Saxon world during the s. Here theosophy refers to the international sectarian movement deriving from the activities and writings of the Russian adventuress and occultist, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky Madame Blavatsky's first book, Zsis Unveiled , was less an outline of her new religion than a rambling tirade against the rationalist and materialistic culture of modern Western civilization.

Her use of traditional esoteric sources to discredit present-day beliefs showed clearly how much she hankered after ancient religious truths in defiance of contemporary agnosticism and modern science. In this enterprise she drew upon a range of secondary sources treating of pagan mythology and mystery religions, Gnosticism, the Henetica, and the arcane lore of the Renaissance scholars, the Rosicrucians and other secret fraternities. Her fascination with Egypt as the fount of all wisdom arose from her enthusiastic reading of the English author Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

It is ironical that early theosophy should have been principally inspired by English occult fiction, a fact made abundantly clear by Liljegren's comparative textual studies4 Only after Madame Blavatsky and her followers moved to India in 9 did theosophy receive a more systematic formulation. This new interest in Indian lore may reflect her sensitivity to changes in the direction of scholarship: Now the East rather than Egyptwas seen as the source of ancient wisdom.

Other Books in This Series

Later theosophical doctrine consequently displays a marked similarity to the religious tenets of Hinduism. The Secret Doctrine claimed to describe the activities of God from the beginning of one period of universal creation until its end, a cyclical process which continues indefinitely over and over again. The story related how the present universe was born, whence it emanated, what powers fashion it, whither it is progressing, and what it all means.

The first volume Cosmogenesis outlined the scheme according to which the primal unity of an unmanifest divine being differentiates itself into a multiformity of consciously evolving beings that gradually fill the universe. The divine being manifested itself initially through an emanation and three subsequent Logoi: All subsequent creation occurred in conformity with the divine plan, passing through seven 'rounds' or i.

In the first round the universe was characterized by the predominance of fire, in the second by air, in the third by water, in the fourth by earth, and in the others by ether. This sequence reflected the cyclical fall of the universe from divine grace over the first four rounds and its following redemption over the next three, before everything contracted once more to the point of primal unity for the start of a new major cycle. Madame Blavatsky illustrated the stages of the cosmic cycle with a variety of esoteric symbols, including triangles, triskelions, and swastikas.

So extensive was her use of this latter Eastern sign of fortune and fertility that she included it in her design for the seal of the Theosophical Society. The executive agent of the entire cosmic enterprise was called Fohat, 'a universal agent employed by the Sons of God to create and uphold our world'.

The manifestations of this force were, according to Blavatsky, electricity and solar energy, and 'the objectivised thought of the gods'. This electro-spiritual force was in tune with contemporary vitalist and scientific thought. The second volume Anthropogenesis attempted to relate man to this grandiose vision of the cosmos.

Not only was humanity assigned an age of far greater antiquity than that conceded by science, but it was also integrated into a scheme of cosmic, physical, and spiritual evolution. These theories were partly derived from late nineteenthcentury scholarship concerning palaeontology, inasmuch as Blavatsky adopted a racial theory of human evolution. She extended her cyclical doctrine with the assertion that each round witnessed the rise and fall of seven consecutive root-races, which descended on the scale of spiritual development from the first to the fourth, becoming increasingly enmeshed in the material world the Gnostic notion of a Fall from Light into Darkness was quite explicit , before ascending through progressively superior root-races from the fifth to the seventh.

According to Blavatsky, present humanity constituted the fifth rootrace upon a planet that was passing through the fourth cosmic round, so that a process of spiritual advance lay before the species. The fifth root-race was called the Aryan race and had been preceded by the fourth root-race of the Atlanteans, which had largely perished in a flood that submerged their mid-Atlantic continent.

The Atlanteans had wielded psychic forces with which our race was not familiar, their gigantism enabled them to build cyclopean structures, and they possessed a superior technology based upon the successful exploitation of Fohat. The three earlier races of the present planetary round were proto-human, consisting of the first Astral root-race which arose in an invisible, imperishable and sacred land and the second Hyperborean. The third Lemurian root-race flourished on a continent which had lain in the Indian Ocean.

The individual human ego was regarded as a tiny fragment of the divine being. Through reincarnation each ego pursued a cosmic journey through the rounds and the rootraces which led it towards eventual reunion with the divine being whence it had originally issued. This path of countless rebirths also recorded a story of cyclical redemption: This belief not only provided for everyone's participation in the fantastic worlds of remote prehistory in the root-race scheme, but also enabled one to conceive of salvation through reincarnation in the ultimate root-races which represented the supreme state of spiritual evolution: This chiliastic vision supplemented the psychological appeal of belonging to a vast cosmic order.

These adepts were not gods but rather advanced members of our own evolutionary group, who had decided to impart their wisdom to the rest of Aryan mankind through their chosen representative, Madame Blavatsky. Like her masters, she also claimed an exclusive authority on the basis of her occult knowledge or gnosis. Her account of prehistory frequently invoked the sacred authority of dite priesthoods among the root-races of the past. When the Lemurians had fallen into iniquity and sin, only a hierarchy of the elect remained pure in spirit. This remnant became the Lemuro-Atlantean dynasty of priest-kings who took up their abode on the fabulous island of Shamballah in the Gobi Desert.

These leaders were linked with Blavatsky's own masters, who were the instructors of the fifth Aryan root-race. Despite its tortuous argument and the frequent contradictions which arose from the plethora of pseudo-scholarly references throughout the work, The Secret Doctrine may be summarized in terms of three basic principles. Firstly, the fact ofa God, who is omnipresent, eternal, boundless and immutable. The instrument of this deity is Fohat, an electro-spiritual force which impresses the divine scheme upon the cosmic substance as the 'laws of nature'.

Secondly, the rule of periodicity, whereby all creation is subject to an endless cycle of destruction and rebirth. These rounds always terminate at a level spiritually superior to their starting-point. Only the hazy promise of occult initiation shimmering through its countless quotations from ancient beliefs, lost apocryphal writings, and the traditional Gnostic and Hermetic sources of esoteric wisdom can account for the success of her doctrine and the size of her following amongst the educated classes of several countries.

How can one explain the enthusiastic reception of Blavatsky's ideas by significant numbers of Europeans and Americans from the s onwards? Theosophy offered an appealing mixture ofancient religious ideas and new concepts borrowed from the Darwinian theory of evolution and modern science.

This syncretic faith thus possessed the power to comfort certain individuals whose traditional outlook had been upset by the discrediting of orthodox religion, by the very rationalizing and de-mystifying progress of science and by the culturally dislocative impact of rapid social and economic change in the late nineteenth century.

Mosse has noted that theosophy typified the wave of anti-positivism sweeping Europe at the end of the century and observed that its outri notions made a deeper impression in Germany than in other European countries. Its advent is best understood within a wider neo-romantic protest movement in Wilhelmian Germany known as Lebensrq5om life reform. This movement represented a middle-class attempt to palliate the ills of modern life, deriving from the growth of the cities and industry. A variety of alternative life-styles-including herbal and natural medicine, vegetarianism, nudism and self-sufficient rural communes-were embraced by small groups of individuals who hoped to restore.

The political atmosphere of the movement was apparently liberal and left-wing with its interest in land reform, but there were many overlaps with the volkisch movement.

Marxian critics have even interpreted it as mere bourgeois escapism from the consequences of capita1ism. In July the first German Theosophical Society was established under the presidency of Wilhelm Hubbe-Schleiden 9 16 at Elberfeld, where Blavatsky and her chief collaborator, Henry Steel Olcott, were staying with their theosophical friends, the Gebhards. At this time Hiibbe-Schleiden was employed as a senior civil servant at the Colonial Office in Hamburg.

He had travelled widely, once managing an estate in West Africa and was a prominent figure in the political lobby for an expanded German overseas empire. Olcott and Hubbe-Schleiden travelled to Munich and Dresden to make contact with scattered theosophists and so lav the basis for a German organization. It has been suggested that this hasty attempt to found a German movement sprang from Blavatsky's desire for a new centre after a scandal involving charges of charlatanism against the theosophists at Madras early in Blavatsky's methods of producing occult phenomena and messages from her masters had aroused suspicion in her entourage and led eventually to an enquiry and an unfavourable report upon her activities by the London Society for Psychical Research.

Unfortunately for Hiibbe-Schleiden, his presidency lapsed when the formal German organization dissolved, once the scandal became more widely publicized following the exodus of the theosophists from India in April In Hiibbe-Schleiden stimulated a more serious awareness of occultism in Germany through the publication of a scholarly monthly periodical, Die Sphznx, which was concerned with a discussion of spiritualism, psychical research, and paranormal phenomena from a scientific point of view.

Here Max Dessoir expounded hypnotism, while Eduard von Hartmann deve! Carl du Prel, the psychical researcher, and his colleagJe Lazar von Hellenbach, who. Another important member of the Sphinx circle was Karl Kiesewetter, whose studies in the history of the post-Renaissance esoteric tradition brought knowledge of the scholar magicians, the early modern alchemists and contemporary occultism to a wider audience.

While not itself theosophical, Hiibbe-Schleiden's periodical was a powerful element in the German occult revival until it ceased publication in Besides this scientific current of occultism, there arose in the s a broader German theosophical movement, which derived mainly from the popularizing efforts of Franz Hartmann 1 9 Hartmann had been born in Donauworth and brought up in Kempten, where his father held office as a court doctor. After military service with a Bavarian artillery regiment in , Hartmann began his medical studies at Munich University.

While on vacation in France during , he took a post as ship's doctor on a vessel bound for the United States, where he spent the next eighteen years of his life. After completing his training at St Louis he opened an eye clinic and practised there until He then travelled round Mexico, settled briefly at New Orleans before continuing to Texas in , and in went to Georgetown in Colorado, where he became coroner in Besides his medical practice he claimed to have a speculative interest in gold- and silver-mining.

By the beginning of the s he had also become interested in American spiritualism, attending the seances of the movement's leading figures such as Mrs Rice Holmes and Kate Wentworth, while immersing himself in the writings ofJudge Edmonds and AndrewJackson Davis. However, following his discovery of Zsis Unveiled, theosophy replaced spiritualism as his principal diversion. He resolved to visit the theosophists at Madras, travelling there by way of California, Japan and South-East Asia in late While Blavatsky and Olcott visited Europe in early , Hartmann was appointed acting president of the Society during their absence.

He remained at the Society headquarters until the theosophists finally left India in April 1 However, once he had established himself as a director of a L. In he founded, together with. Alfredo Pioda and Countess Constance Wachtmeister, the close friend of Blavatsky, a theosophical lay-monastery at Ascona, a place noted for its many anarchist experiments. In the second half of this decade the first peak in German theosophical publishing occurred. Both series consisted of German translations from Blavatskv's successors in England, Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, togither with original studies by Hartmann and Hubbe-Schleiden.

The chief concern of these small books lay with abstruse cosmology, karma, spiritualism and the actuality of the hidden mahatmas. In addition to this output must be mentioned Hartmann's translations of the Bhagavad Gita, the Tao-Te-King and the Tattwa Bodha, together with his own monographs on Buddhism, Christian mysticism and Paracelsus. Once Hartmann's example had provided the initial impetus, another important periodical sprang up. In Paul Zillmann founded the Metaphysische Rundschau [MetaphysicalReview], a monthly periodical which dealt with many aspects of the esoteric tradition, while also embracing new parapsychological research as a successor to Die Sbhinx.

Wright were travelling through Europe to drum up overseas support for their movement. Hartmann supplied a fictional story about his discovery of a seiret Rosicrucian monastery in the Bavarian Alps, which fed the minds of readers with romantic notions of adepts in the middle of modern Europe. This Wald-Loge Forest Lodge was organized into three quasi-masonic grades of initiation. In his capacity of publisher, Paul Zillmann was an important link between the German occult subculture and the Ariosophists of Vienna, whose works he issued under his own imprint between and Theosophy remained a sectarian phenomenon in Germany, typified by small and often antagonistic local groups.

In late the editor of the Neue Metaphysische Rundschau received annual reports from branch societies in Berlin, Cottbus, Dresden, Essen, Graz, and Leipzig and bemoaned their evident lack of mutual fraternity. I8 However, by , the movement displayed more cohesion with two principal centres at Berlin and Leipzig, supported by a further ten local theosophical societies and about thirty small circles throughout Germany and Austria. April , opened a theosophical centre in the capital, while at Leipzig there existed another centre associated with Arthur Weber, Hermann Rudolf, and Edwin Bohme.

While these activities remained largely under the sway of Franz Hartmann and Paul Zillmann, mention must be made bf another theosophical tendency in Germany. In Rudolf Steiner, a young scholar who had studied in Vienna before writinc " at Weimar a studv of Goethe's scientificwritings, was made general secretary of the German Theosophical Society at Berlin, founded by London theosophists.

Steiner published a periodical, Luzifer, at Berlin from to Astrological periodicals and a related book-series, the Astrologische Rundschau [AstrologicalReview] and the Astrologische Bibliothek [Astrological Library],were also issued here from Hartmann's earlier periodical was revived in under the title Neue Lotusbliiten at the Jaeger press, which simultaneously started the Osiris-Biicher, a long book-series which introduced many new occultists to the German public.

It was written by Richard Matheson and directed by Terence Fisher. Set in London and the south of England in , the story finds Nicholas, Duc de Richleau Christopher Lee , investigating the strange actions of the son of a friend, Simon Aron Patrick Mower , who has a house replete with strange markings and a pentagram.

He quickly deduces that Simon is involved with the occult. During the rescue, they disrupt a ceremony on Salisbury Plain, in which the Devil Baphomet appears. First proposed in , the film eventually went ahead four years later once censorship worries over Satanism had eased.

Christopher Lee had often stated that of all his vast back catalogue of films, this was his favourite and the one he would have liked to have seen remade with modern special effects and with his playing a mature Duke de Richleau.

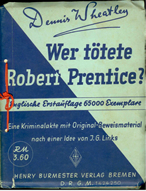

Doing some "light" reading. Automatic writing, blindfold, with a planchette. Bound into the book are telegrams, police reports, crime scene photos and three dimensional clues like burnt matches and hair. The reader attempts to solve the mystery and the solution is in a sealed pocket in the back. This and others from the Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult now in stock. The Devil Plays Canasta odeonofdeath cinema pastiche christopherlee denniswheatley occult View.

Current Re-read denniswheatley devilridesout pulpnovel View. Marvellous edition of The Devil Rides Out just added. The novel served as a template for the Hammermovie thedevilridesout with christopherlee Thelema abbeyofthelema gothic occultbooks occult occultism grimoire spellbook witchcraft occultbook lefthandpath bookstagram bookseller View.

Happy Halloween, part 4 denniswheatley blackmagic magic horror arrowbooks supernatural horrorfiction halloween halloween halloween book books bookish bookstagram bookcover bookcollector novel novels bibliophiles bibliophile paperback paperbacks story occult british britishhorror View. Excited to revisit this one thedevilridesout christopherlee richardmatheson denniswheatley terencefisher charlesgray hammerfilms View.