Sansuka and Sasrutha are old old men, Dad says they would be 26 now. He calls me baby and gives me piggy-back rides when he visits. Dad says Sasrutha went to Toronto to be with his boyfriend and ended up being a travel writer. He has been everywhere except Mars and always sends us copies of his articles with his very own notes inked in. Sasrutha always ends up getting a mango worm in his head or needing money for bail, his articles are pretty funny.

Ominotago we call Minnow and she is only four years older than me but she calls me baby-baby, which I like when Sansuka calls me that but not her. Sometimes I call her Fishbreath. Dad says he used to be a no-good layabout before he met Mom, and then he became a good daddy BOOM like that. He also says Wild Eagles is a dumb name but they chose it because they got tired of news reporters mispronouncing their own language at them.

Dad tells stories to the tourists who come up by airtrain now. And the government found out she was a terramancer and told her to go north and make the hinterlands where we are better for tourists. She had signed up to be an organ donor so we stayed at the hospital overnight while the doctors took out her eyeballs and heart and things. They sort of stitched her back up and we drove home. Minnow and I went to school like always in the school bus but when we got out Mom was waiting to take us home.

Minnow started crying and got on the bus, but I let Mom pick me up and she ran all the way home with me on her shoulders. Your mom eats brains! So the next day I told Tammy I was sorry for throwing rocks at her but if she ever said anything bad about Mom again then next time I would make her eat them. The stone is comfortable, for stone. Its door is a single sheet of ill-fitting particle board, with a twisted-up wire coat hanger for a knob. It would be impossible to not hear what her teacher and her principal are saying, and since they are talking about her she feels it would be rude not to listen.

He looks like what a bear would look like if it were human. She is, need I repeat, a zombie. She just stays outside all day, waiting for school to be let out. Meoquanee leans a little to look out the front door. Her was-mother is standing on the single flagstone outside, waiting for Meoquanee to come out so she can run her home. At recess her was-mother stands over her like a patient vulture. At home she does it to Minnow. Tell was-Jivanta not to look after her children?

Meoquanee can hear papers being shuffled. And the dead still have rights. As long as they are mobile, they will be treated with the same respect you would give to anyone, regardless of their physical or mental quirks. Meoquanee loses interest in the conversation. Tautologically, no muscle is used until it is used. Her arms dangle flaccidly. Even her neck is cantered at a loose angle, lolling occasionally when Meoquanee waves. The voices on the other side of the door continue to speak, absorbed in the intricacies of matters which do not concern her.

There is no verbal response. Are you a religious man? Some people find it a comfort. Frankly, I think zombies are living, ah ha, proof that there is no God. No loving God would do this to His children. If that could be arranged. Papers are picked up and shoved roughly into a satchel. Chan needs to leave at 4: Was-Jivanta is running in great leaping bounds. The sewn-up skin of her emptied belly flops inside her dress, creating an oddly hypnotic ripple in her silhouette. Her arms bounce up sharply with every heavy impact of her hiking boots on the dirt road.

Chan does not tolerate tardiness, has threatened numerous times to leave Mrs. Johansen alone if he is not back by 4: Sometimes he wonders what would happen if he took her up on it. Minnow and Meoquanee are in their room. Minnow is trying to do her homework, but her was-mother is standing right behind her. She has been pretending it was a tree with a lake beside it, but the wineglass tension distracts her from play.

She looks up to watch her was-mother, not motionless, but swaying gently in the faint breeze of the room. Suddenly Minnow yowls like a cat and slams her math book shut. She hurtles out of the room, roughly shoving their was-mother aside. Was-Jivanta bumps into the wall and gently collapses. Meoquanee drops her string and her sock and watches her was-mother stand, using her legs and the wall and nothing else. Ahmik is on the futon. The TV is on, the one channel showing something from the House of Commons. Everyone sees it but Minnow.

Ahmik gestures to her to sit beside him. Minnow crosses her arms instead and sets off a furious pout. Ahmik keeps his hands out. Ahmik turns from tired to annoyed, limp to sharp. Was-Jivanta stands there, rocking back and forth gently as Minnow punches her. Meoquanee, with the wineglass feeling in her bones, rushes over and shoves Minnow as hard as she can.

Minnow stumbles into the futon. Ahmik catches her before she tumbles. Minnow is looking at Ahmik and Ahmik is looking at Meoquanee and Meoquanee is looking at was-Jivanta and was-Jivanta is. Ahmik breaks the cycle. Minnow wrenches away from him, ducks around was-Jivanta and throws herself back into her room. The door slams and there is the thunk of a latch slotting into place. No, not at you. Not at Minnow, either. She feels his hand judder and bumps her head against his thigh.

She was an organ donor, and they tend to come back as zombies. And… well, she was very attached to her work. Each of you had your own jar. Sansuka and Sasrutha and Keezheekoni and Minnow and you. He puts the jar back and sits next to her. She snuggles into him, but her eyes are for was-Jivanta. Ahmik takes his time answering. She runs really really fast.

There is a horrible panicky sound to his voice that makes Meoquanee want to sit down and bawl.

He brushes past was-Jivanta and tries the knob. There is no answer, but was-Jivanta solves all the problems by hurling herself once more at the door. The latch breaks and she falls inside the room. Before he can even turn around, was-Jivanta is up and diving through the window. Ahmik snaps at Meoquanee to stay here! Ahmik stares at his was-wife and realises, with the pinpoint accuracy of those in shock, that he is having a deeply profound and unsettling epiphany. Was-Jivanta takes Minnow inside.

Ahmik goes to the shed where the water coolers are kept. Near the coolers are a shallow metal pan and a tuning fork. Water is the great medium of all transmissions and the blood tunes the call to the individual. You tap the tuning fork and get it humming and stick it into the water and let it buzz itself out, and then dip your ear into the water and talk like normal.

The person on the other end gets a persistent buzzing in their ear, and if they want to talk, they just lick their pinkie finger and stick it in their ear. A hydromancer on vacation set it up for Jivanta. Ahmik taps the tuning fork and sticks it in the water. It seems to take a long time for the water to stop twitching, and he lays on the dirt with his head in the pan.

Was-Jivanta brought her back pretty much soon as she left. But I think I should tell her. I wanted to talk to you two first. See if it was a bad idea. There are too many years of swallowing words and bottling feelings to let them out over a hydrocall. She never liked doing it when she was alive. They would react like Minnow, ignoring the importance of that odd exhalation….

He dumps the pinkish water outside on some rocks and replaces everything in the shed. His family does have a bad habit of running away from each other, but it occurs to Ahmik that for the first time, was-Jivanta might be running towards. Inside the house, Meoquanee is sitting on the futon with her knees up and her arms around her legs. The TV is on, a voiceover commentating soberly on two lines of people shouting at each other. This group has taken credit for the dehumanisation of zombies in several American states in the past year, and border police are warned to be extra-vigilant in the coming weeks as the Gay to be Grey zombie walk prepares to kick off in Ottawa in July.

The righteous also rise! These people were all willing donors. Ahmik kisses her on the top of her head. Ahmik takes a deep breath. Ahmik crouches down and puts his hands on her shoulders. Meoquanee claps her hands to her ears. Minnow screams like a throat-singer, one continuous note, rising and falling. Eventually the noise dies down. Was-Jivanta is standing, swaying in that way she has. Minnow is curled around her feet, snoring like she does. Minnow stays home from school the next day. Was-Jivanta runs Meoquanee to school as usual.

A little after lunch, when Johansen is talking about chlorophyll and photosynthesis, Jacy walks into the room and takes him aside. Meoquanee, at the front of the class so she can crane her neck to see her was-mother outside, hears these words: Then the phone slams down and Johansen is back in the classroom, grabbing his coat and shooting words over his shoulder to Jacy. I have to go. Jacy shuts the door again as Meoquanee pushes her chair back.

He saw the look Johansen gave her, and he remembers the homework assignment. He addresses the class. Johansen bites her sometimes. Before Jacy can answer, another voice pipes up. Johansen was your mom. No sooner does Jacy pull Meoquanee off Tammy Gabriel than was-Jivanta is in the room, kissing-close to Jacy and showing him her teeth.

Jacy pulls his hands away from Meoquanee and ducks down to check on Tammy, bleeding from the nose and crying. Meoquanee is breathing hard, and she and her was-mother seem to be trying to stand protectively in front of each other at the same time. Meoquanee sits on the edge of her chair, hands gripping the seat. Was-Jivanta is out the door, but not out of sight. The other kids fidget, glance at Tammy and her red-spilling nose.

Jacy gets her some tissues and tells her to keep her head down. His pacing slows, his hands raise up and slash down, creating notes on an invisible blackboard. Plantlife Plants Life was one of hers. While vacationing in Iceland, she fell into a fissure and was retrieved some six hours later. Unfortunately, she had broken a lot of bones in that fall, and she died some three hours later in hospital.

True to her reduce-reuse-recycling nature, she had signed up as an organ donor and what parts were still functional were duly taken out. Her body was put on a plane to be sent back to her native Sweden for burial. When the plane landed, ground crews were understandably taken aback to find Ms. Stjerna had freed herself from the airplane coffin during flight. Stjerna spent the rest of her days roaming Padjelanta National Park, where sightings of her eventually became as legendary as those of the Loch Ness Monster, Elvis Presley and Godzilla.

The same student raises his hand again. Died , at age eighteen. Eyes were all they could harvest from him. Ollie Brown goes into the hospital morgue and not long after scares the skin off a janitor who came down to investigate some strange noises. Janitor finds Ollie Brown up and about. Ollie Brown did not yet have a mortician put his bones back into more or less place, did not have anyone pretty him up with pancake make-up and make him presentable to the family.

Ollie Brown is a shuffling, shambling mess, and it does not help that the janitor had some fairly right-wing hang-ups which do not bear going into. Jacy sits sidesaddle on the desk and draws his lips down. He was sentenced to five years in prison. No one could have survived that motorcycle crash and then had his eyes taken out without kicking up some kind of a fuss. Plus there was that security video showing Ollie fighting for fifteen minutes to get out of that drawer in the morgue, and then stumbling around on half his legs.

The Criminal Code of Canada changed. Tammy glares at Meoquanee over the soiled wad of tissue in her nose. Jacy claps his hands. She talks a little about her dad and mentions her brothers. Meoquanee gets a paragraph of complaints. Johansen needs more attention these days. Attention, and maybe a muzzle.

As zombies have proven, sometimes just being there is enough. The next day is Saturday, and Ahmik and the girls ride in the pick-up. Was-Jivanta lopes along beside the truck. The road is just dirt piled onto more dirt. Eventually he stops the truck in front of a hill and they get out, bringing a picnic basket with them. Ahmik walks them up the hill and all of a sudden an amethyst post comes into view. Minnow is already running her hands over the post, over the upside-down bear totem carved into it.

Ahmik sets down the picnic basket. The amethyst comes from his mine. Maybe you girls remember when we had Aunt Ying stay with you for a while? I was here with Keezheekoni. Suddenly she stops stroking the amethyst post and slaps her hand on the ground. Ahmik sighs and runs his hands through his hair. They sit in a circle which includes the post.

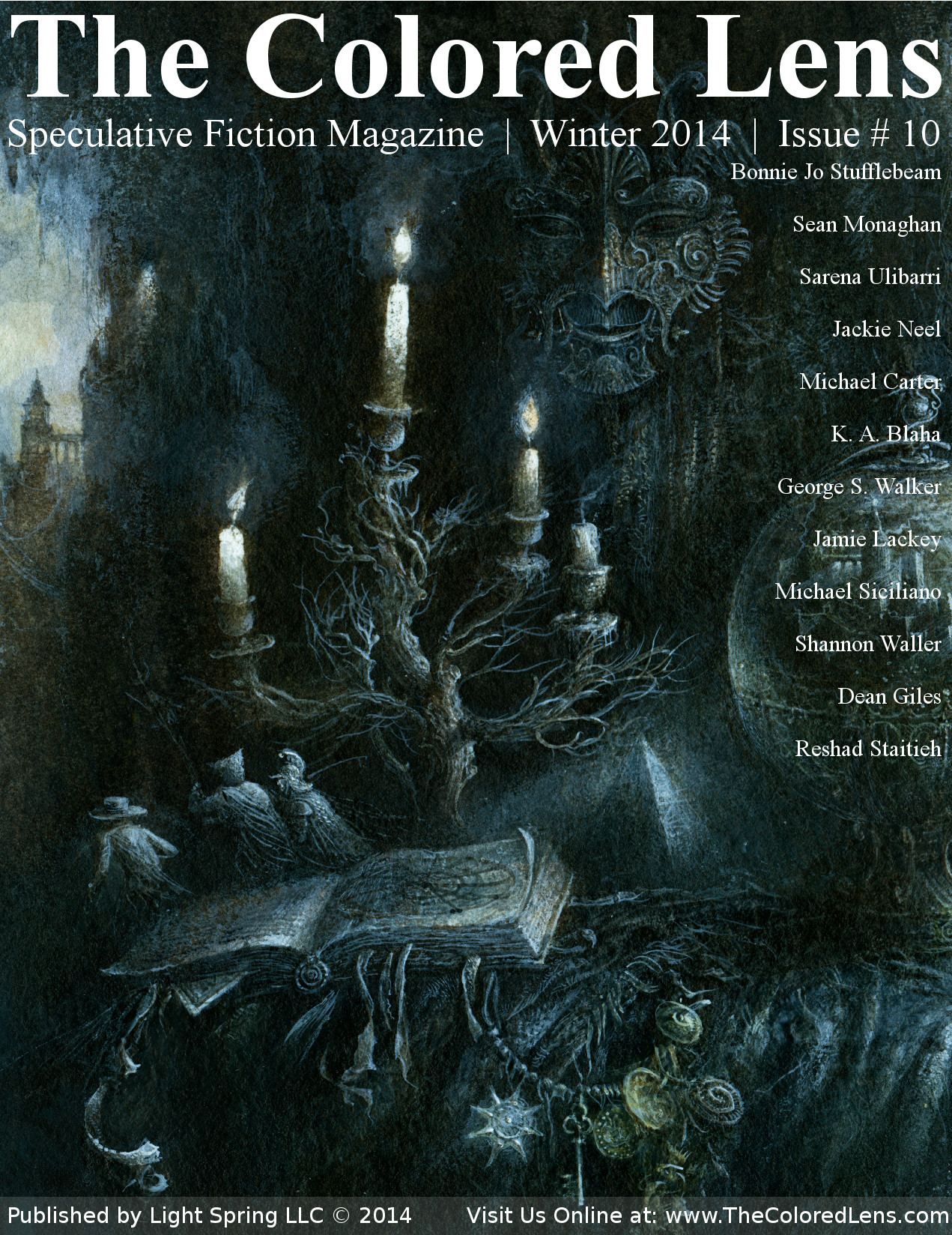

The Colored Lens #14 – Winter – The Colored Lens

Her voice trails away as the scent rolls over the hillside. When she came here… Jivanta had never divorced her husband. She came all the way here with the boys to get away from him. But, if you agree to work for us, we can offer you protection and a new life. Publicly, she was sent north to make the land better for tourists. Privately, she was used to find the children in the Tooth for a Tooth War. It was very sensitive, politically — she pretty much had to give up her identity.

And she decided it was better that way. He sets the dirty mason jar in front of him on the grass. As a terramancer, Jivanta could change the very earth itself, make it sand or loam or grow things you never thought possible up here. She could change the shape of the land itself, make a hill where a valley had been. But you can do so much more with terramancy than just play with dirt. Do you remember the summer we let her stay with Sasrutha? For Meoquanee, the concept of murder is barely understood.

Her face is wet and she feels her own nose running. While the rest of us were holding vigil, your mother was hunting the murderer. Minnow and Meoquanee stare at their was-mother, their mouths as slack as hers. Ahmik shakes his head. I wanted to tell you girls, at least that Keezheekoni was dead, but Jivanta thought it would just make you ask more questions.

After Keezheekoni died, it was like she — ran further away. Sometimes Minnow brings up a memory. Meoquanee barely talks and frequently goes to was-Jivanta to hug her legs. They spend the day there, exploring the land around the gravesite. They leave before nightfall, when Ahmik can still recognise landmarks. Was-Jivanta is still in front of the lodge. They do see her next week. And the next, and the next. More like her hollowed-out belly is getting filled in. He asks her, sometimes. The girls are happier, or at least healthier.

The family hurries over, more confused than concerned. They have to squint against the afternoon sun. They circle around was-Jivanta. The thick black thread holding her skin together has been taken out, and inside the cavity where her organs used to live is a pile of dirt. Minnow looks in the little lodge. I held my breath, sincerely wondering how Allan would answer. But it was Elise who answered: I crept away as quietly as I could, unsure whether the sound I suppressed was a sob or something more like bitter laughter. It was a over a week later, and storytime was definitely over. I tried not to think of Allan as I stared into an expanse of prairie grass.

It spread like a yellow-green ocean from the light on the back porch to the end of the known universe, losing color the farther it went into the night. Finally I could see nothing but the phosphorescent glow of hundreds of lightning bugs: No, not stuck, my editor-mind corrected: Marooned and emotionally mutinied by a pair of pirate daughters who had always loved their daddy better.

I wiped my hand across my forehead just as a wave of breeze skimmed across the ocean of my back lawn, in through the open window and over my face, turning me suddenly cold all the way through. The screen door slammed on the back verandah and I jumped up to face my girls. She held something behind her back as she stood shifting with excitement from side to side. I tried to smile. Little Kari, hands over her mouth, looked as though she was about to burst. She held the mayonnaise jar high in front of her like a trophy.

Ragged holes had been punched in the plastic lid, the label peeled off leaving only smudgy streaks of glue obscuring its contents: I took the jar from Elise, still studying her expression. Not a fairy; not a real one. Probably some toy I gave them and forgot about, I thought. I laughed at my gullibility, and raised the jar for a closer look.

The figure sat turned away from me, presenting me with coppery hair and greenish wings. Holding my own breath I turned the jar around. There she was, not a toy at all, cast in intermittent lightning-bug light. About three inches tall, fair-skinned and naked, she sat on the twig with her bare feet on the glass bottom of the jar and her head in her tiny hands.

One of the lightning bugs—to her the size of a barn owl—buzzed around her head, and she shooed it away with a violent wave of her arm. She picked her head up and fixed me with fierce green eyes. My grip on the jar slipped. I set the jar on the kitchen counter. Kari scrambled up onto one of the stools on the other side of the counter, perching on her knees with her elbows on the formica countertop.

She peered into the jar like a cat looks into a fishtank, still grinning. The tiny woman threw her hands up in the air. I shook my head, feeling like I was moving underwater. The little creature stood up in her ounce world. Kari squealed with joy, talking a mile a minute.

Nope, not this time. Elise and Kari giggled, and I wondered if it was about the bug or the naughty word. Maybe I can destroy you with a snap of my fingers. Once again she was dive-bombed by a lightning bug, but she simply pointed at it and the bug blinked out of existence. Her arms were crossed over her naked chest, her foot tapping impatiently. Iris flew out, stretching her wings, as did one of the lightning bugs. The other bug seemed content to throw itself repeatedly against the glass wall of the jar. Elise seemed to consider this, eyes rotating in their sockets to follow Iris, flying in loop-de-loops in our kitchen.

She looked more than a little frightened, Elise, and I thought I should say something to comfort her. But what was there to say? I re-screwed the lid, locking the remaining firefly inside. In a small way I mourned its missed opportunity for freedom. You snooze, you lose, I thought, and with that, unbidden, came thoughts of Allan. Iris flew around, floating like a butterfly with her nude legs trailing behind. Iris set down on the counter, stretching upwards with her arms.

Kari reached her arm across the countertop to get my attention, whispering loudly enough for everyone to hear. You people are all the same. I shrugged, looking into my own empty wineglass. Iris sighed loudly, and I imagined I could see her roll her bright green eyes. She paused, while I mentally searched the house for a thimble. Relieved, I crept out to the back porch with an opened bottle of Pinot Grigio, and lit a cigarette.

She sat on the edge of the table between them, legs swinging in the night air. I exhaled a lungful of smoke at her, watching as she basked in its carcinogenic fog. She laughed, leaning back on her elbows on the table. A few caps of alcohol had made her far less cantankerous. I put my hands up, backpedaling.

She glared at me. Her eyes seemed to be made of emerald light; sometimes they shone, other times they pulled light into them like twin black holes. Somewhere coal is burned to turn water into steam to spin a turbine to make electricity, which travels for miles to get to your house. You flip a switch and the light comes on, like magic. I looked out at the waving field of prairie grass, trying to see it as anything but a wasteland. The lightning bugs had all gone to sleep, along with the few neighbors we could see, and it was quiet, quiet, quiet.

Sometimes I thought I could hear it snoring, rumbling like an approaching summer storm. Her wings out of sight behind her, she looked just like a woman in miniature. This time I laughed too. Well, he always comes back eventually. Not that it matters much. Iris did the same, then extended her toothpaste cap to me. I took it, dipped it into the wine in my own glass, and handed it back to her.

She looked at me, startled. The next morning I woke to the sounds and smells of breakfast, and for an instant I thought Allan had returned. And then I remembered the previous evening. I stumbled downstairs to the kitchen, where Iris was flying above the stove. Under her command breakfast literally made itself, spatulas hanging in the air waiting to turn slices of French toast and bacon. She was still naked, of course, and I wondered how she avoided splatter burns. Kari busied herself setting the dining room table—four plates, but only three with glasses and silverware.

Kari scurried past me holding a carton of orange juice and a jug of syrup, while Elise huddled next to the stove, watching intently as Iris hovered over the frying pans. Seeing that there was nothing I could do to help I sat down at the table. Before I could even pour myself some orange juice Iris and my girls came into the room, preceded by floating plates of food that somewhat unsteadily set themselves down on the table. She smiled, breaking off a crumb of French toast with her hands and carrying it to her plate. She just shrugged and stabbed a piece of French toast with her fork.

I looked to Iris, hoping to catch some sort of answer in her gleaming eyes. But her head was bowed away from me. Ebullient and oblivious as always, Kari broke the silence. As her attention settled on my younger daughter her wings drooped. The little fairy shrugged, moving wings as well as shoulders. Her sadness was palpable, so many times bigger than her. It hovered around the table as if borne by transparent wings.

When we finished eating, Iris cleaned our plates with one sweeping wave of her arm. Like that the syrup and crumbs and the little white strings of bacon fat that Allan used to eat but none of us liked were dispatched, perhaps to some other realm. I heard myself giggling, imagining the dimension of banished items. A land piled high with table scraps and lightning bugs, but also with secret treasures stored for safekeeping, with precious children and irritating lovers. Elise shook her head and Iris watched her, an appraising look on her face.

The fairy was grave. It may be the hardest thing in the world. Not enough to pick up the phone, anyway, and once again be the first to crumble. It had always been easy not to answer when his cell number appeared on the caller-ID; the calls were never for me. But it seemed like even the girls missed him less with Iris around.

Who needed Allan when there was magic in the house, a little more magic each day? Even better, she was very patient with the girls, taking the edge off the long summer days that would ordinarily have had me begging for year-round schooling. Every day I felt I ought to be looking for a new job, but then I would remember where I was and laugh out loud at my nonexistent options.

Having been let go by the college, what was there for me? You could see stars blink on almost one-by-one, mirrored on earth by the creepy staccato blink of hundreds of fireflies. Warm nights were a relief after sweltering days, and Iris and I would sit on the verandah and sigh into our wineglass and toothpaste cap.

Iris fidgeted with her cap of wine, picking it up then setting it back down, then picking it up and passing it from one hand to the other. I covered my eyes with my hand and squinted, but I could only see the shapes of my daughters hunched in the grass. They were just figures outlined against a backdrop of tiny green lights blinking on and off. I pulled myself out of the low chair, feeling huge and ungainly and suddenly excluded, and stepped into knee-high yellow grass. I came up behind Elise without her noticing, she was so focused on something in front of her.

In front of her, fireflies blinked on and off and she watched them, intently. I knelt behind her and watched what she watched. As my eyes adjusted to the dark the lightning bugs came into better focus, and I could confirm visually what I knew intellectually: I blinked my eyes and shook my head, hoping to clear whatever distortion had produced the effect, but as soon as I opened them I saw it again.

The light was snuffed and the bug was gone. I said it calmly, but she jumped so high she almost fell over. She turned and looked at me with saucer eyes. I stood up, startled by a tug on the back of my shirt. Twirling around I saw Kari, lifting a jar high in front of her for my approval. In the jar were four lightning bugs, and I stared at them for a long time.

Stumbling back onto the solid ground of the porch I felt my heart racing. Iris was still sitting on the edge of an overturned ashtray that served as a bench, and when she looked up at me her tiny face was blank. I wavered between sitting and standing before dropping into my chair.

I looked at her, overcome by a sick feeling in my stomach. To become a witch? Iris just started laughing, bobbing up and down like a buoy. I like you, Deb. So relax, and stop saying stupid things. I grabbed my wine glass and went back into the kitchen to re-fill it.

Damned uppity fairy, I thought. First Allan and now her. I thought of calling Allan, making him come back. I had the feeling it would fix everything that was broken, but something stopped me. It would fix everything but you. I wandered around the house. Everything sparkled a little more than it used to; it seemed fresh and clean, but also unfamiliar and subtly menacing. The room was a sea of lavender, her favorite color. Every surface was covered with either stuffed animals or books, and they all seemed to be watching me with dark accusing eyes.

Her bedside table and the floor in front of it were littered with library books. Setting my wineglass down I picked the top one up. They were all on similar topics. The topmost book on the floor, The Magical Encyclopaedia: R — V, had a rainbow-colored bookmark sticking out its top, festooned with a red yarn fringe. I picked up the book, opening it to that page. There were a number of entries in the two-page spread, but one of them was marked with a penciled-in star. The degree of difficulty—and danger—varies with the object being summoned, with even small inanimate objects requiring a moderate to high level of magic.

I whirled around to see Iris shaking her finger at me as if to say shame on you. Guiltily I picked up my glass and took a step toward the door, but as I got closer I saw that Iris was smiling. Diminutive as she was, I was tinier still. What does she want to summon? In her eyes I saw encouragement tempered with frustration and mockery. I re-filled my glass, then changed my mind and left it in the refrigerator. Taking a deep breath I stepped onto the porch, where both girls were sitting on its edge.

Go brush your teeth, okay? I had to smile; at least she seemed unchanged.

The Colored Lens #17 Autumn 2015

Elise started to follow her little sister. I sat in the place Kari had occupied, unsure how to begin. I looked up at the bright carpet of stars, but they were silent, inert. I decided to lie. Elise looked at me like I was a lightning bug she hoped would disappear. I sighed, dropping the pretense. It was probably my imagination, but in that instant her brown eyes seemed to glow green. But this time it stopped before slamming, settling into its frame without a sound. I sat there for a long minute, looking out into the prairie grass.

Fucking Ohio, I thought. Fucking Allan, fucking college, fucking prairie grass. As if on cue Iris flew out the door holding her toothpaste cap in one hand, preceded by my wineglass. The wires in your house can only handle so much, and if you try to pull more through them they. So what do I do, smarty? I felt like grabbing her, crushing her in one hand, crumpling her into a ball like a piece of winged junk-mail.

She floated lazily up and toward the house. I fumed at her for a moment, then went into the house. The air seemed shimmery, unstable, and the hair on my arms stood on end. Pressing my ear to the door I thought I heard murmuring, though it might have been the reflected sound of blood pounding in my ears. Otherwise the house was as quiet as it had ever been, which added to the spookiness. Was she trying the summoning now? How would I know? Did magic have a sound? I rapped on the door with my knuckles.

I knocked harder with the side of my fist. Stepping back from the door I examined the handle. Maybe if I got a paper clip or a bobby pin I could pick the lock. Not just warm, hot, and getting hotter all the time. I pulled the gold ring over my knuckle as it started to burn, and quickly dropped it onto the hardwood floor. It clattered to a stop, emitting a mild glow, then it wobbled once and slid purposefully under the gap in the door.

Ignoring her insult I continued. You have to stop before you hurt yourself. I blinked, and opening my eyes I saw the little naked fairy hovering over Kari. She was peering into her eyes and feeling her forehead with the back of her arm, as Kari smiled sleepily back at her. How could I not have known her wish? I thought of the wine, and the secret smoking, the three of them all awake before me, making breakfast. My girls used to help me in the kitchen all the time.

I shook my head, blinking in the increasingly fuzzy air. My head was starting to hurt, and I felt dizzy. I leaned against the wall for support. The voice coming through the door sounded hard, yet brittle, like it could shatter. I love—Ow, what the fu. Turning it around I saw that, of course, it was a picture of Allan. But I knew how I looked: Like an evil stepmother. My eyes were wet as I looked up from the picture, and the door looked blurry. There was a pause, during which I almost thought things would be okay. Of course I did. I shouted as much.

I pounded on the door again, pulling on the handle. I looked around the hallway for something to break down the door with, but there was nothing. There was only Kari twitching on the floor, and Iris hovering over her. There was only me. The fairy glared at me. Then she suddenly smiled, in a way that made me sick to my stomach. I will never forget that smile. The glass in the picture frame shattered. I heard things move all over the house, falling and thumping and clattering like loose stones in an earthquake.

Kari was stirring on the hallway floor, murmuring like she did just before waking. It would be simpler than the truth, and truer than it too. I was starting to think he was way outside cell range. There was a lot of talk in that small town, especially when the police investigated me for killing my husband and daughter. Perhaps Allan had been cheating, they said. I started working as a freelancer, refusing to move from the farmhouse and the town that I had never loved and hated more and more all the time.

Kari grew up, as children do, and went off to college on the west coast. She married and had kids of her own, two boys, and then divorced while they were still in school. I spent many years alone. I grew older than I ever thought I would, until I was so old that I became young and helpless again.

One day I was woken from an afternoon nap by the sound of the front door swinging open on squeaky hinges. A young man and a little girl walked tentatively through the door, looking with shock and fear at the house they thought they knew. Kari came in from the kitchen then, and dropped whatever she was carrying with a clatter and splash. Still he came over to me and held me in his arms. My own tears spilled over my eyelids and ran down a wrinkled, unfamiliar face. The world is water. From horizon to horizon, water. Trade winds go from west to east, and carry weather and fish with them.

Wind and weather bring us news of the world, in the form of all manner of things that float. A string of islands are our own, we and the cousins. Fifteen islands, from tiny Ike to the largest, Yuhime. Ours is the northernmost, Liipil, an island that catches the winds, the volcano beneath dead as our ancestors. As you go south, the land becomes more active, and the cousins become more numerous. The youngling who had been assigned to the northern heights plummeted into the village, calling shrilly.

The ikei are returning! After putting my work away, I swung down, landing heavily at the base of the great starflower tree that the platform was built in. I was going to have to start climbing down rather than swinging, soon. I had years yet before I would be too heavy to use the platforms altogether, when I would have to have those younger than I fetch and carry from the platforms. Not too old yet to run, though. I trotted through the village, joined by younglings and adults, down to the landing field. It was a good and welcoming landing place for the ikei, our pelagics who spent most of their time at sea, circling the world with the trade winds, following the great sea-herds of whales and fish.

Kii and Liiloka had brought food with them, voyage-fruit and sweet tik-tik, and we settled down to eat and wait. A flock of younglings arrived, swirling down to land lightly, grabbing and squabbling over tik-tik. A few stretched out, settling to turn the leaf-scales on their backs to the sun. Kii stumped over to me, her massive body and her fronds of lichen making her seem like a particularly mobile boulder. She held a quarter of a voyage-fruit out to me, and I accepted with a murmur.

A shout came from the gathered younglings, and several of them fluttered up into the air. I turned my eyes to the sky. Dark wings against blue sky, bodies stout with months of feeding and flying. Their wings were enormous, spans ten times the lengths of their bodies, and patterned wildly underneath. I strained my eyes, looking. So many patterns, stripes and swirls and eye-spots. But there were only twelve of them, a twentieth of the number we expected to return.

This would be the largest group, most of them young, having banded together for their first year at sea. The older ones would return by ones and twos over the next few weeks. For now, we fussed over the ikei who had returned, gathering around them, running hands over their wings as they preened and crowed.

Their long heads with the bone crests at the backs were objects of much fuss and admiration. I stood apart from the crowd, as did those others who had favorites who had not yet returned. None of us were interested in finding out which of these ikei might fill us for the time they were here, because we already had our choices.

Lilleloi came to me, crouched down and gestured for me to join her. Lilleloi was younger than me, with the litheness of youth still on her and her back still more leaf-scales than lichen. She had found a favorite the year before, and from the way her stubby tail twitched she, too, was nervous that he would not return. Merely inexperience; her chosen ikei, Jerul, was younger than she and strong enough that unless accident befell him he would return. I shook my head, raising my hand to search through the lichen at the back of my head, an old habit. But the reunions are worth it.

I took a bite of my voyage-fruit. Pelagics forget who they are on land as soon as they lose sight of it. He says that this life stops when he takes to sea, and resumes when he comes back. He only vaguely remembers the journey once he touches land. That night, as the sun set, we gathered in the village. I climbed up to a platform and watched the younglings show off for the ikei, dancing with their wings spread, patterns painted on them to mimic ikei patterns. Adults watched from the shadows beneath the trees. There would be no couplings tonight, or any night until we were sure that most of those who were going to return had done so.

Those with no favorites wanted the widest choice possible; those with favorites would wait until those favorites had returned. If the favorites did not return, they would choose another, probably from this group of young ikei. Some of the younglings had caught a small cousin, a six-limbed swimming thing with wide membrane between its pairs of forelimbs. They showed it to the ikei, who fanned their wings gently in approval and put their eyes close to it, their long heads tilted so more than one could see at once. I would suggest that you just ask Him. I have faith in you. God works in the strangest of ways.

I know the answer will arrive for you in time. All the pastor had done was to paint him into a dark corner. Perhaps there was another way. He stared at the contract in his hand without any idea what to do. When he looked up, the pastor had gone, and the stones, millstones, burned with a fire hotter than the afternoon sun.

It was as if they called to him, almost beckoned him to do something. Mike stood at the base of the water tank and rapped his knuckles on the side of the corrugated tin. He did it on every rung until he had reached the lowest; the one below the outlet, and it was only then that the hollow tone changed to indicate water.

It only confirmed what he knew. He sat on the floor with his back resting against the empty tank and stared at the distant hills. Two days had passed since his meeting with Chris Owens, and with it the final drops of their main water supply. His flock of sheep stood idle in the midday sun around the water trough. He tried to massage the tension away at the side of his head, but it made little difference. He knew they would, but Mike would rather keep his farm, and continue living the life expected of him. A lifestyle he loved. He heard Maisie Jane and Anna laughing inside the old family farmhouse.

It filled him with joy. Maisie Jane had been immune to what was going on around her thanks to Anna. It was all Maisie Jane talked about while she recovered from her illness. They would find a way to survive on an old corroded tank by the side of the house, one that took water from the farmhouse roof. It was a small tank. What was the old bush motto: He grinned in spite of his somber mood. He marched down the hill to the farmhouse and crept inside and grabbed the car keys, intent on letting Anna and Maisie Jane play in the next room.

On the way into town he took the longer route, the one that went past the bottom paddock where the hydraulic fracturing well was going to be sited. He pulled the car up on the verge and stopped. From the side of the road, the area looked picturesque. A small valley with gentle hills to the left. The quiet solitude embraced him. He stepped outside, and the morning sun warmed him. Sound pollution would probably not be an issue: Mike clambered over the fence, and it was as if it triggered the stones in the canvas bags against his chest.

It always happened as soon as he walked the land near to the cave that the three emeralds had come from. Fire smoldered at his neck. He ignored it as best as he could, unsure why the stones always became agitated around this place. It was as if they had a life of their own and they yearned to be put back in the ground where they had come from.

Mike would never do that. But he twisted his neck uncomfortably against them. Even the Poseidon Stones. Mike had ignored the warning once and dared clamber into the cave. The dark narrow cavern hummed. It was a magic place. Mike clambered out of the cave as fast as he could. Keep them apart, like insolent children. Mike pulled them out, away from his skin and breathed a sigh of relief. He had to admit that they were magic. In their own way, they were alive. Who knew what they would do. The once-wet depression was bone dry. The dragonflies that once hovered over the water pools were gone.

In the distance, off to his left the low rolling hills were already burned gray from the early start to summer. Nothing lived at this spot. The drilling company was welcome to it. He put the fiery stones around his neck back under his clothes and took comfort in their closeness. The other stones in the cave would remain intact, far enough from the clutches of the miners and their drilling for gas. It sat outside the drilling area, and that was all that mattered. Everything was quiet in town, as if it slept in the midday sun. Mike strode into the mining office this time and asked for Chris Owens.

He waited until Chris Owens signed it. So I can buy in some water. Chris Owens smiled again. You know, in case we find anything different from what we had initially expected. Tomorrow at the latest. Fence off the site. Get the dozers in. I can get one of the site guys to take out your copy of the contract if you like? Saves you waiting around. Mike left the office. Instead, an uncomfortable knot twisted in his stomach. Somehow, he had to find a way to make their supply last over the next week. Mike stood and raised his voice. Mike pushed open the door and strode outside.

What had he done? What did she want him to say? If only he had asked before signing. A dragonfly darted back into the shade by the water tank. It positioned itself in a pocket of shade. To Mike, it looked as though the beautiful insect had minimized its body to the sun, and it used its four huge wings as reflectors. The heat was draining. He remembered that the cave where the emeralds were located was next to the edge of the site boundary. What if they damaged that area by bulldozing it?

What if they uncovered it? In the distance the sound of a hammer striking metal made him stop in his tracks. He heard an engine start up. Fear kicked in and he ran toward the bottom paddock as fast as he could. The stones around his neck came alive like wildfire.

Mike looked around, amazed at what he could see. The corner paddock looked like a construction site. A perimeter fence was going up, and men were banging in posts. A bulldozer was leveling the land nearest to the roadway.

Get A Copy

Ripping up the vegetation into a mound. The driver of the dozer stopped and turned off the engine. He stepped down off the heavy machine. His chest warmed where the stones were, and he moved them. The drilling head is being installed tomorrow. I was heading down to deliver your signed contract. What seems to be the problem? A dragonfly whipped past.

They darted about, intent on their solitary missions.

See a Problem?

It hovered in more of a dance than anything else. This was where they had camped all those years ago. Back when there had been water and the dragonflies swarmed the place in abundance. The cave entrance, hidden by a large rock beckoned. He was as trapped as Lucky had been that night in the cave. The dragonfly returned with another, and they hovered nearby. Mike watched the prehistoric-looking insects with interest. Dad had always called them the jewels of the sky.

In the sunlight they dazzled. Their large green eyes looked like big emeralds. Mike touched his neck chain. They looked like the stones. One hovered, and the other zigzagged left and right. It stopped and then flew backward. It seemed so random. Before, when there was water. It was like a watershed. The tension fell from him. He pulled the stones out from under his shirt and removed each of them from their small hessian bags. Even through the silk cocoons, they burned in his hand. It all made sense now. He turned back to the man who had stood patiently. There was another way.

He smiled at the man. Endorsed by the local company director. I would like to respectfully ask you to move away from the site until we can put up a perimeter fence. You can watch the works from the other side once the perimeter fence is up. You have a three-day cooling off period before you can start.

He tore the contract in half and in half again and threw it onto the ground. You are now trespassing, and I would respectfully ask you and your company to leave. The man stared back at Mike for the longest moment, and finally he smiled. Tell him I have all the water I need. Mike strode from the drilling and construction team. They had no choice. He made his way near to the cave and positioned himself on the high ground, where he had camped all those years ago.

Dragonflies were an ancient insect, and had taken to the air long before any of the dinosaurs walked the Earth. They always appeared around ponds and lakes. And there they were. Not one or two, but hundreds of them. They hovered in the dry paddock where the lake once was. Like a sea of emeralds. Mike stared at the three silk parcels in his hand.

But everything is connected, and all this time the power of the Poseidon Stones had been hidden in plain sight. Poseidon was the god of water, and the dragonflies, with their big emerald green eyes had hinted to where there was water. Why else would there be so many dragonflies in abundance? It was as if they hovered and waited for him. He pulled one out of the stones from its silk cocoon and let it fall onto his hand. It was as if someone had slid a rough piece of wood along the side of his head. The warm stone seemed to come alive.

It pulsed inside his head. He pulled out the second stone and placed it alongside the first. Pain shot through his head and it grew to a deep throb within him. He wanted to let go of the stones. Quickly he let the third stone fall onto his open palm before he lost all courage. It was as if someone had smacked him on the side of the head with a brick. His heart skipped a beat. His hand felt as if it was on fire. He closed his eyes and bit his lip until he tasted blood and fought not to let go of the stones. He took a breath and braced himself, then closed his hand around the stones so that they joined.

He thrust his hand out. The pain in his head grew and he doubled over. The ground shook around him and the fire seemed to burst from his hand, or the stones. A bright flash illuminated through his closed eyelids. He winced and shut them tighter. He opened his hand and let go of the stones. They fell, and the pain vanished. He opened his eyes, convinced his palm would be burned, but it was unscathed.

He bent and retrieved the stones, one at a time, and he placed them back in their silk cocoons and returned the magic Poseidon Stones to the small hessian bags on the chain. He glanced over at the spot where the lake had once been and smiled at the massive swarm of dragonflies. In that small moment, the swarm had multiplied and there had to be a thousand or more there now. They hovered over the old lake and darted in chaotic style just above the ground, to where water bubbled up from a rent in the Earth. In that time he had unshackled the water pump and moved it beside the edge of the lake.

Mike watched Maisie Jane run in and out of the water and splash in it. A car pulled up by the road and a man stepped out. Anna waved, and Mike recognized Pastor Matthew. He strode down and joined them. Imagine there being water just below the surface all this time. There was more than enough water for the animals and the family, and Mike would be able to lavish the oak seedling they had planted. Anna squeezed his hand back. He saw several dragonflies and smiled. One darted backward and hovered above her head.

Its emerald colored eyes glistened like the stones. They made him feel more alive. More connected to the world than Mike ever thought possible. They pulsed with a beat deep inside him. I wanted to shout, to scream. Instead I held my hands before me and saw nothing but the crimson carpet. I wept and wondered that even my tears were invisible.

They held each other until they both fell asleep, their eyes red and their faces pale. But, as is the wont of terrible things, time passed and they became less terrible. The trees in the garden turned a burnished orange and then powdered white and then a flushing green and occasional laughter could be heard through the house and it made my heart cold to hear it. I should have felt joy in their happiness, but a man can turn melancholy, drifting quiet and alone in his own house, unnoticed and unseen.

Did the dead eat? I had to do both, and then hide in the basement, shivering against the cold until I had digested the food. She was wearing makeup and a red dress. The trees in the garden were heavy with snow. I roused myself in the corner. What day was it? Every day merged into one when there was nothing to do but wander disconsolately around the house.

Lisa would look at him with serious eyes and Steven would smile and tell jokes and help around the house. Nobody smiled that much. Had I ever smiled that much? When they were out, I would go through the photographs and see myself smiling. I stood in front of mirrors and saw nothing. I clasped a hand to my head. Lisa liked this guy.

She was only six. Or was she seven now? The birds chattered on budding trees and sunlight streamed through the kitchen window. The brightness hurt my eyes and my head. Lisa was asleep when they returned and Steven carried her from the car and into the house. The sight made me weep and clench my fists. He was evil, this man. I wanted to kill him as he drove. No, first I wanted proof of his evil intentions. I wanted to know what it was I was saving my family from. I lay on the back seat and watched the ghastly glow of the streetlights smear the darkness of the night.

I imagined pornography parading on walls and handcuffs hanging from bedposts. Instead I got an apartment that was neat and fashionably sparse. He checked his messages when he got in. Five calls to his mother. He would ignore them and chat to women on dating sites.

But instead he called his mum on his mobile. He sat in a reclining chair, loosening his tie. Misses her dad, course she does. Listen, are you going to be in on Sunday? I slipped into the bed as quietly as I could. Hannah rested her head on my shoulder, snuggling in and breathing deep. When the first breath of sunlight touched the window, I went to see Lisa. She was fast asleep clutching a toy bear. I stroked her hair. She clutched the bear tighter and smiled. My hand shook as I opened the door. The morning sun was shining, and as I took one last look back at the house, I saw my footprints were already fading in the dew-wet grass.

An Indiscernible Amount of Things. Outside there is only death. Wren had learned these words almost twenty years ago, as part of a nursery rhyme. Hunkered down in the passenger seat of the crawler, waiting to set out on his first assignment, it was all he could think. Reentry would mean a quarantine lasting more than a week.

So far, that at least had worked; there was no record of contamination within Hub. When the last set of doors slid open and the crawler passed through, Wren only stared without a word. He blinked at the sun until his eyes stung and began to water. Wren turned, then, to gape at the clouds. They billowed upward, dwarfing those in the museum exhibits, putting to shame the clouds in his head. Below, level with the crawler, there was just a vast, green expanse of thickets that rose and stretched about Hub.

Wren had to keep reminding himself that it was fatal, too. The landscape moved along in silence for almost two hours, without a word between Wren and the driver. They passed abandoned cars and structures punctured by vines, as they navigated around dormant warheads, deep craters, and crippled, grinning signs. In the distance, a dark building loomed over the ruins, still intact, like the last bottle in a sea of glass. The forward canopy snapped open and the two men climbed out, letting themselves down over the tall wheels. Wren held back as the driver approached the doors and keyed in the entry code, sending a signal to Hub.

It was the only communication left outside their dome—just that request lighting up on a display panel somewhere back home. As they waited for the Hub technicians to verify entry, Wren felt the terror all around him, creeping through the pale film of his suit. It was like knocking on a door two hundred miles away. What if the filtration on their masks broke down while they waited, as it had for the old man?

Wren glanced at the driver. He stared placidly ahead, carrying only a latched tablet. Glass and fabric—that was all that protected them from the air outside. How could he be so calm? Wren almost dropped his case when the steel doors unfastened themselves, peeling back to allow entry to the decontamination chamber. They stepped inside, and the driver tapped the lock, sealing the entrance behind them.

Wren could see nothing through the mist as it pooled around their bodies, wiping them clean. Piles of random objects clogged the hallway, nearly meeting his waist where he stood. He unlatched the imprint tablet and handed it over. Wren watched the doors as they swallowed the man. He waited, and listened as the crawler sputtered to life outside the building and trundled away. After a moment, he turned and fell to his knees. For the first time in his life, Wren was completely alone. The tower had been built during the war. Each building employed a series of ventilation systems, backed by separate fail safes.

When the city died, and power failed, the structure fell back on solar energy to keep the air inside clean. Wren had to repeat this to himself several times before he could take off his mask. Even so, as he set the white mask on the ground, he expected his lungs to fill and burst, to leave him drowning on the floor. When nothing happened, he took a deep breath and began to look around. The tower extended twenty floors upward. In the final month before his departure, Wren had studied the blueprints at the Academy each night.

Each floor measured about five thousand square feet, and had been packed with items brought in by the scavenger crews. Outside, the walls were covered by black solar panels, and each window had been reinforced with several layers of bulletproof glass. Wren sat in the hallway, staring at the closest stack of things.

They lay in pieces, in fragments spaced apart, as though the objects had forged the path themselves. The scavengers had been careless. And yet, how could he fault them? They had spent most of their time outside the building, where the threat of pierced clothing meant contamination, and a slow, wasting path to death.

Tidiness was not their concern; it was his. He sighed and stood, bringing his case to the empty room by the entryway. For the long year to come, Wren had been issued seven days of clothing to be cleaned by hand. Each garment was identical to the last: He had also been given a stiff mat and a thin set of sheets, which he unrolled and laid out on the floor as his bed. Wren took the hallway to the left, searching for the store room. The first transport was due in three months, but he had been assured a six month supply cache was already in place.

The room was filled with jugs of water, cases of broth, and twenty crates of High Nutrition Sustenance. HNS was dry, bitter, and difficult to chew, but there was no threat of contamination, and it lasted almost indefinitely. They had left a separate supply of water for bathing, along with a few jugs of soap, and several hundred small packets of disinfectant.

In the room next door, he found a small bathroom with two dubious looking toilets set against the wall. He lifted the lid of one and looked in. There was no bowl, just a long, black drop below. Wren straightened up and walked back to the store room, opening a packet of HNS. He chewed slowly, trying to keep the bar from touching his tongue. After he ate, Wren set out for the stairwell. Wren had to brace the door with his shoulder and press with all his weight to get in.

The hinges groaned with age, echoing into the black distance above. There were no windows in the stairway, just old lights left along the wall like dead eyes. He gripped the handrail and climbed the first set in the dark. The second floor was laid out the same as the first: Near his feet a stuffed doll with red, curling braids lay ripped at the shoulder. He waded across the room, stooping down to examine a scarf, and then a small stone carving—pale, transparent, a short man with a plump belly. Wren placed each item he examined back among the heaps, tapping his hip idly, memorizing approximate positions and compositions, making minor calculations and estimates in his head.

Wren had spent his life from the age of ten studying items he had only seen in photos, or behind glass. Wandering among the piles, he was mesmerized by it all, picking up an old watch or rusted necklace to feel the weight of it in his palm, pressed between his fingers. None of these things would ever be his, and yet—for this year—each one of them was. Wren climbed six more floors before the dark began to grow. In Hub, there was always light. Another thing to get used to, he thought: Careful not to fall, he made his way down the stairs slowly, gripping the rail.

Each floor would have to be organized on its own, and Wren calculated almost forty thousand items altogether. To meet the deadline he would have to sort at least two floors each month. Wren paused as he stepped back into the main hall, surveying the room, and began to laugh. The sound startled him, crawling along the steel walls and spreading about his feet.

He gripped his arms and stared out the tall windows of the first floor. Beyond the crumpled buildings and fractured highways, there seemed to be nothing but a dark, vast silence stretching out before him. When the first quarterly transport was due, three months later, it was either a day late, or Wren had marked the calendar wrong. He waited in agony, avoiding his work—restless, prowling the floors, and peering through the great windows at the verdant landscape below.

Clouds bellowed and broke, until they were swallowed by the darkness. He returned to his room in a sour mood. Had they forgotten him? As a student, Wren had isolated himself with his studies, but now he longed for Hub—yearned to see another face. He wanted to hear speech, to know there was someone else alive in the world beside him.

Wren turned over on the hard mat, begging for sleep to take him. His dreams the next morning were broken by a low, puffing thunder. Wren blinked, then tore off his sheets and scampered to the entrance of the building. His heart skipped and hammered as he watched the crawler idle out front.

He pressed his face to the glass, waiting for someone to emerge. After a moment, the driver dismounted, and opened the hollow at the back of the crawler. Wren backed away, giddy, waiting for the man to approach and enter the codes. As the second set of doors pulled back, groaning, Wren rushed forward, then stopped and backed off a little, unsure of himself—shy. The driver peered at Wren through the white impasse of the mask.

The driver grunted in assent, and they shuffled over to the load. It was just as Wren should have expected: Hiding his disappointment, he reached up and grabbed a crate, then fell into step alongside the man, directing him to the store room as they went.

The driver sighed and took off his mask, setting it on the floor. There was a kind look about him. Wren tried to smooth the mass of hair that fell in front of his own eyes, and glanced away. The scavengers go out in groups, and only for a month at a time before they rotate. Do you ever wonder why that is? Wren stood there for a moment, stunned as the driver walked back to the dolly. He dashed back, catching up as the man hefted another crate. They carried the last of the crates in silence.

Wren wanted to ask something else—anything—to begin another conversation, but he felt mute, unable to manage a single word. He found himself repeating his own words in his head, forgetting the man that still walked beside him. It was only as the driver stood at the doors, fidgeting with his mask, that Wren remembered his presence. Wren stepped back as Kai entered the decontamination chamber, then watched, squinting through the windows as the crawler pulled away. Wren had been born into the academic caste.

When he was five, contact with his parents had been cut off and he had entered the Academy. It was an honor, but it had cost him contact with his peers. When the others gathered for sport in the atrium, or migrated to the commons to mingle, often trailing off to copulate, Wren would be the last one in the library, nose deep in a text. At the time, he had consoled himself with the notion that what he was doing meant something, and was greater than himself.

There were regulations in place for his work, but they were no more strict than anything else in Hub. Everything has a reason: That was the answer to every question in Hub. Hub, as they learned as children, had been built as an experiment. It was a government project, an extension of the Mars Initiative, a trial for a giant dome on the red planet—self-sustaining, and sealed off from the environment, with an initial population of one thousand.

When war came, and the germ spread across the country, Hub was the only population center left unaffected. The castes, the Academy, the enforcement sector—all of these were established at the same time. For each safe building beyond the dome, one sorter was designated, and replaced only at death. When the items were retrieved, they were distributed between the upper castes. As each day passed in silence, and the nights stretched before him, Wren would remind himself of the honor of his task, like a lullaby, as he tried to fall asleep. Even so, it seemed the floors rose endlessly above him, heavy with their things.

Each day followed the same pattern: Wren sorted, and he ate—he defecated, and he slept. As the months swept by, he dreamed of the piles. They lay out in front of him in waves, writhing, no longer items, but people—naked and charred, reaching out at him, tearing at his face and trying to draw him in. Sometimes, he dreamed of the old man.

After the worst of the dreams, Wren would wake in a sweat, shivering. Unable to fall back asleep, he would get up and pace the floor by the windows, staring out into the darkness for hours on end. When the second transport came, Wren worked quietly beside Kai, saying little as they carried the supplies.

Once they finished, and the man was turning to go, Wren managed to say what had been weighing on him for months, in the silence. Kai laughed gently and knelt down, sifting through a pile of items sorted into the most valuable tier. Wren flinched as he touched them. How long ago did this happen? How they formed the caste system in the name of survival, arguing that panic might cause a breach, and contaminate Hub.

That we needed order; a structure to maintain the survival of our species. So our parents put their heads down. We were born into the life we were born into. How does any of this enable the survival of our species? They put some of it in the public museums, true, but most of it goes on their walls.

Anything dangerous is incinerated. Certain works of fiction. The sort of work that made Kunin see how wrong everything is in Hub. Twelve years ago, he began to smuggle in books like that. Last year he was caught. They made the others watch as they stripped Kunin naked and pushed him out into the open. I could turn you in. Even before what happened with Kunin, they would have. Wren—you must realize that none of us know what else is out there. We are led to believe that the entire world is dead and poisoned beyond our walls. But how can that be true? The world is vast, and within Hub we are slaves to the caste.

There must be others alive out there, beyond Hub. And we could go on equal footing. But first, we need books. We need to keep the words alive, to reach others. Wren opened his mouth, but said nothing. He watched as Kai put on his mask and punched the lock, stepping through the doors. It felt like the world and everything he knew was slipping away, piece by piece. The moment Kai left, Wren found his head swimming with questions. How did Kai organize with the others without being caught? How many of them were there?

- The Black Swan;

- The Science Fiction, Fantasy, & Weird Fiction Magazine Index?

- The Colored Lens #9 – Autumn – The Colored Lens.

- The FictionMags Index.

- Back Issues – The Colored Lens.

- Contents Lists;

Wren only grew more impatient with the questions as each day passed. Soon, he began sorting through the stacks of books with a new purpose. He sought out history books and works of theory with new interest, no longer sorting them into the piles. His studies at Hub had only showed him small details, never the whole picture, and it had left the past of their species obscured.

Wren discovered anarchism and democracy, socialism and slavery. He read about the holocaust and the crusades, the Cold War and the Great War. He discovered an endless amount of religions, and with each, the wars waged in their name. The more Wren read, the more divided his thoughts became. There was no war within Hub, no religion, and yet there was a class system every bit as rigid and precise as those abolished centuries before their time. They were safe within Hub, so long as they played the role they were born into. Did it matter if the privileged had their pick of all these things?

Most of all, he yearned for human contact. Often he spoke as though Kai was there, making arguments about the caste system and staging debates. By the time the third transport came, three months later, Wren had come to think of Kai as a friend. At last he could ask his questions, and have a real answer. Wren waited at the doors, unable to contain a grin. As they unfastened, and a figure appeared in the receding mist, Wren rushed forward, embracing the man. There was a shuffle, then, and the man backed away, waving his arms.

Wren sat on the floor by the entrance until the man finished with the crates and left. As it pulled away, the sound of the crawler seemed so much smaller, and softer, than it had in his memory. Wren climbed and sorted three more floors in the next month. Even then, he was behind.

He had made new calculations, and at his pace, he would only be to the eighteenth floor when the auditor came. Still, all he could do was move through one item at a time. He clung to this as he worked, as though it was all that was left to keep him from sinking into darkness. He rose each morning to leave a black mark on the calendar before climbing the stairs to the floor he had left off on.

As Wren sorted through the piles, doubt began to take hold. He was unsure of himself. Everything he had been doing made so little sense. Who was he sorting for? And to what end? Wren lifted a necklace from one of the piles and watched as it glimmered and burned in the light. What would these things do for the people that received them? Everything he sorted would hang from necks, on walls, like Kai had said—like trophies, like severed heads.

Wren cried out and flung the necklace against the wall, watching as the gems shattered and flew from their chain, cascading about the room. After a moment he fell to his knees, scrabbling to preserve what he had broken, to collect all the pieces, feeling as though he had taken a life. Wren began to doubt each decision he made. Why was one thing worth more than the other?

He knew the method, of course—historical value, level of preservation, the materials used—but he was losing the point, and his judgment was failing. Instead, at night, he would walk to the great glass windows and stare out into the void that lay beyond. Wren would watch the empty distant black, just letting his mind go for a moment. There, the days swung round, repeating themselves like a strip of film.

He marked it off the calendar, smiling a little. There was a jar of pitted, preserved cherries he had found among the piles. He had read about them in his time at the Academy, pouring over the images longer than he should have, memorizing their shape and texture, imagining their taste.

They were extinct, and if somehow they were still preserved, they would fall into the highest tier. Wren took a breath and unscrewed the lid. He had lived through the motions a dozen times in his sleep. After a moment he dipped his fingers into the jar and stuffed one into his mouth. His eyes softened, then shut tightly, and he spat the cherry onto the ground, gagging. Rot filled his mouth, and he sat down, his cheeks burning as he sobbed, rocking, cradling the jar.

Wren was nearly half way through the sixteenth floor when another vehicle came. He was just picking up a silver hand mirror, the glass shattered, when he heard the ragged churn of an engine in the distance. The mirror slipped from his hand and clattered to the floor. He dashed to the windows, frantically trying to place the vehicle that approached.

Wren fled down the stairs, counting the floors as he vaulted a few steps at a time. Near the third floor he fell, wrenching his ankle and cursing, staggering up and limping the rest of the way. In his room, Wren stood gaping at the calendar, staring at the empty page. It came over him slowly, the memory creeping up and settling around his throat like a noose: He listened as the footsteps echoed through the building.

Just one set, like cannon fire. Wren wondered if that was how his steps went as they paced around the building, unaware of themselves. The voice sounded his name once more, sharply. At that, the terror holding Wren in place broke, and he rose, sprinting from his room to the entrance, trying to ignore the pain in his ankle as he ran.

Turning the corner, he stumbled to a halt in front of a man he had never met, who eyed him with a look of distaste. He still wore the white suit, though he had taken off his mask. Instead, he turned away from Wren and began to stroll about the first floor, thumbing a noter as he walked. It was a statement, not a question. The man looked older than Wren. His hair was dark, worn slicked back over his head. Some sort of jelly, Wren thought—something found by another sorter. Auditors were part of the governing caste, and Wren realized how he must look to the man.

Wren began to smooth his hair nervously, pulling it back over his head and draping it behind his ears, imitating the man. He opened his mouth to speak, but all the questions—everything he wanted to say—seemed to jam together and catch in his throat. Only a hoarse whisper escaped. He closed his mouth and turned away, shuffling over and pretending to examine one of the tiles. Again, he was conscious of gaping at the man. Of course he knew that. He would have done it at the end, after everything was sorted.

He swallowed, then, remembering that several floors were still untouched. Wren looked at the man, and began to stammer. Everything the auditor said seemed to come with a sigh. They moved through the rest of the floors as Wren explained how each stack had been organized, or pointed out a treasure of note, showing the auditor why a painting had been set aside in the lower tiers due to a gash in one corner, or why a dark bottle had been left to the highest tier: When they reached the last floor sorted, the silence enveloped them. He had shown the auditor the final piles, lingering where he had left off, clinging on to each item as though it was the last foothold at the end of a long climb.

Wren eyed his feet. His toes protruded from the worn shoes, and his nails curled back into the flesh. The man sighed, and noted something. They walked slowly, climbing the stairs and standing a long while at the entrance to each floor. Wren watched as the auditor took his notes. He knew, then, that he had no control over what happened next.