His passion and intelligence are ever present throughout the book and Megill's commentary save Marx gets an A for ingenuity and incite into the human experience but an F for clarity and practical implications. His passion and intelligence are ever present throughout the book and Megill's commentary saves the reader from needing to be as intelligent as Marx truly was.

Unfortunately, the practical implications of this radical economic theory were rather devastating. Tanner rated it really liked it Mar 26, Tim rated it really liked it Jun 20, Paul rated it really liked it Oct 24, Bookshark rated it really liked it Jan 13, Logan Robert rated it really liked it Aug 31, Maria Pantazopoulou rated it really liked it Aug 29, Christina Fedor rated it it was amazing Aug 16, Hamlet rated it it was amazing Nov 19, Lucy rated it really liked it Jul 13, Tony added it Oct 23, Anthony Buckley marked it as to-read Feb 26, Dariuz marked it as to-read Nov 15, Jesse marked it as to-read Feb 15, Ecology So marked it as to-read Oct 03, Renan Virginio marked it as to-read Feb 12, Aayush marked it as to-read May 24, Daniel Keichi Leite marked it as to-read Aug 08, Jane marked it as to-read Aug 08, Mohammed Vaseemuddin marked it as to-read Nov 26, Olivia marked it as to-read Apr 25, Meng Tsun added it May 12, Jason marked it as to-read Oct 16, Prasanna marked it as to-read Oct 30, Chris marked it as to-read Jan 29, Daniel marked it as to-read Mar 30, Todd marked it as to-read Mar 31, Bjorn Delbeecke marked it as to-read Jun 01, Matt marked it as to-read Jul 16, Mar marked it as to-read Feb 04, Anup Gampa marked it as to-read Mar 27, Norton, , et passim; Here Megill echoes Robert Tucker's view of the German Ideology as "a restatement, minus much of the German philosophical terminology, of the theory of history adumbrated in the manuscripts of " MER, With the same ease he waves off Althusser's notion of an epistemological break by simply asserting that Althusser's claim is "widely recognized" to be "vastly overstated" The outlines of Megill's portrait of what Marx's materialist conception of history "actually was" are pre-drawn by his mutually reinforcing over-contextualization of Marx as a nineteenth-century rationalist and his decision to use one paragraph from the Preface to the Critique ofPolitical Economy as the definitive presentation of that conception.

With this starting point and content, it is not surprising that Megill views Marx's materialist conception of history as another of his attempts to produce, not a "heuristics," but a "global theory" Not content with this depiction, Megill insists further that if we take "theory in the sense in which it is usually taken in analytic philosophy and in social science, to mean a set of propositions that can be used to explain something," then it is not really a theory at all, but a "view or perspective," a "deductive structure," Nor does it provide "a method at all As a set of rigid, pseudoexplanatory propositions, the materialist conception of history is "a relic" that should be dismantled and discarded.

Pointing to Marx's empirical studies that provided data allegedly contradicting it, Megill concludes that Marx himself "was not committed to the materialist conception of history in any deep and doctrinaire way" Aside from his confusing medley of categories," the more important issue is that Megill arrives at these conclusions by discounting key methodological discussions, actually "there" in the German Ideology, that state unmistakably how he intended his general theoretical statements to be understood and used.

By discounting these methodological qualifiers and overstating the similarities in the Manuscripts and German Ideology, Megill produces a materialist conception of history that certainly is a rationalist relic-but not Marx's. And it is precisely here, at its source, that an exegesis of Marx's materialist conception of history must engage in "extended discussion" of a possible "transcendence of philosophy," of possible epistemological and methodological breaks.

Though based on a Feuerbachian philosophical framework, the Manuscripts also exhibit several new socioeconomic and historical themes and ideas. Visible in the last. As will become clear, I agree with Althusser on the timing of the epistemological rupture but not on its character. I cannot address this medley here, but I must comment on the related and more important term, Wissenschaft. Megill rightly states that the early Marx "viewed politics under the guise of Wissenschaft" in the Hegelian sense that it "imposes severe rationality criteria" on its analytical object.

See a Problem?

Generally, however, Wissenschaft means the systematic study of, and body of knowledge about, a given subject. My argument in the following is that Marx abandoned the severe rationalism of Hegel's and his own early notion of Wissenschaft and developed the experimental guidelines of a materialist Wissenschaft of history.

Manuscript, the "Critique of Hegelian Philosophy and Philosophy in General," is Marx's dawning realization that these new ideas could not be contained by the old framework. This is what pushed him toward his "settling of accounts" with his earlier philosophical conscience, toward his Aujhebung of philosophy. As Megill notes , this last manuscript does not really contain a systematic reckoning with Hegel. But reading that manuscript not as the product of a thinking machine, but as an attempt by a living, thinking person to come to terms with the intellectual context he inherited, to reckon with the two greatest intellectual influences on him, and to solve problems that he recognized in his own previous works, yields at least two interesting results.

One is that this last manuscript, compared with the earlier one on "Alienated Labor," shows a new interest in history. Marx's analysis of alienated labor "proceed[s] from an actual economic fact" -that "the worker becomes all the poorer the more wealth he produces. What interests me here, however and Megill as well, , is Marx's attempt to explain the origins of alienated labor. With tortured and totally unsatisfying logic, Marx provided a circular pseudo-explanation of the relation between private property and alienated labor. His lack of success here resulted from having attempted a philosophical explanation of what he increasingly saw as a historical problem.

This points to the second interesting thing about the last manuscript: Though still criticizing the "otherworldly" character of Hegel's philosophy, Marx also praised his insights about history being produced by human albeit intellectual labor. As a result of this new interest in history Marx reconsidered Feuerbach's thought and pronounced his verdict just a year later in the the German Ideology: With him materialism and history diverge completely.?

Marx's new project in the German Ideology was to integrate Hegel'8 historical and Feuerbach's materialist insights, the combination of which pushed him well beyond a mere synthesis of their philosophies. One way to test my claim for a qualitative break in Marx's development is to consider whether he could have written Capital on the methodological assumptions and with the conceptual apparatus of the Manuscripts.

Megill would answer affirmatively. Though he makes a prefatory point of his decision to forego an analysis of Capital, he issues, without having made the case, an anticipatory. There is no doubt about the continuity of certain themes throughout Marx's intellectual life. But the obvious point is that the presence of the same elements does not mean that they have the same meaning, the same methodological place-value, nor that they are articulated with the same conceptual apparatus.

My contention is that had Marx not abandoned the conceptual and methodological framework of the Manuscripts, nor been deeply committed to his materialist conception of history, he neither would have, nor could have, written Capital. The conceptual indicator of Marx's qualitative break with his philosophical past is the fate of the Feuerbachian conceptual and methodological framework of the Manuscripts.

As noted above, that framework required Marx only to proceed from alienation as "an actual economic fact" and to catalogue the ways in which that alienation separated people from the human "species-essence" [Gattungswesen]. But, as Megill also notes, "the most important critical notion in the Marxian armamentarium" in Capital is "exploitation" xx.

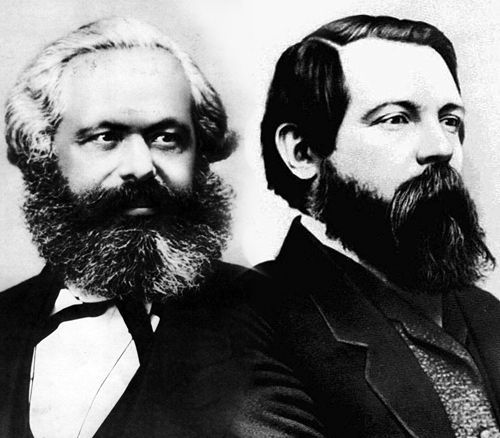

Karl Marx - The Burden of Reason (Why Marx Rejected Politics and the Market) (Electronic book text)

The origins of this focus on "exploitation" and the demotion of "alienation" are to be found in the German Ideology. Beginning with that work, "alienation" from a human "species-essence" no longer functioned as the methodological linchpin and nor held the place of conceptual honor. Thus in the sixth of his Theses on Feuerbach Marx supplanted the notion of an a priori human species-essence with the "ensemble of social relations. But "exploitation" is not just "alienation" by another name.

Account Options

Deeper than "alienation," rooted not vaguely in "history" but concretely in specific sociohistorical forms, the category of "exploitation" demanded a new methodology. If the Feuerbachian methodology required Marx only to describe the various dimensions of alienation, the materialist conception of history developed in the German Ideology required him to explain those dimensions and the other debilitating consequences of the capitalist labor-process as embedded in and produced by the normal func. Cambridge University Press, -but completely neglects its argument, and maintains that "no adequate historical study of Capital has yet been written" xxi.

Perhaps he does not consider Postone's book a "historical study. In a way that registering the "actual fact" of "alienation" never did, Marx's newfound focus on "exploitation" forced him to explain its origins in the "mode of production" and especially the "social relations of production" -categories quite absent from the Manuscripts, but derived from his materialist conception of history, and indispensable to the writing of Capital. The Capital that Marx wrote was made possible because he pursued the epistemological, methodological, and categorial consequences of the historical theorizing that went into the development of his materialist conception of history.

Had he written Capital from a Feuerbachian framework, the result would have been a much different and rather tedious book-a kind of economic version of his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy ofRight. Megill recognizes the German Ideology as "the most important," but also the "lengthiest" presentation of Marx's materialist conception of history.

He therefore chooses "to simplify matters. The latter's "greater compression" makes it "a more apt candidate for explication" and "brings to light fissures in the historical materialist view that are not so readily visible in other, more leisurely accounts" Though the unpublished German Ideology needed much editing, the Feuerbachian section at least is anything but "leisurely. Megill's choice to ignore this "most important" text for the compressed version is fully in keeping with his treatment of Marx as a thinking machine: But his choice to let the compressed version stand for the materialist conception of history as a whole does indeed do "great violence to the overall view" -and precisely by "simplify[ing] matters.

This violence is most visible in Megill's dismissal of Marx's methodological insistence in the Preface that the statements he was about to make served as the "guiding thread for [his] studies" -heuristic statements that outline an approach to the material, if you will, but certainly do not provide an explanatory grid. Assuming, however, that these statements compressed into one lengthy paragraph are the complete and fundamental propositions of the materialist conception of history," Megill reduces Marx's methodological insistence on their heuristic character to "evidence of a certain distancing" from their truth value.

Viewing the writing of the Preface in historical context, which included Marx's justifiable fear of the Prussian censors who could have prevented the book's publication and distribution, Arthur Prinz "Background and Ulterior Motive of Marx's 'Preface of ' ," Journal ofthe History of Ideas 30 [], has argued that Marx consciously did "violence" to his own theory by specifically avoiding any mention in the Preface of class and class struggle, and therefore that the purged discussion in the Preface cannot be considered an adequate summary of Marx's materialist conception of history.

But the "guiding-thread" comment only indicates "distancing" from their truth value if the statements were intended as apodictic propositions. To insist that they were, that Marx intended them as the framework of a "deductive structure," of a pre-established "global theory" with absolute and immediate explanatory power, is to neglect "what is there" in this passage and in the comparable one in the German Ideology that the Preface echoes. In a crucial methodological discussion in the German Ideology, Marx insisted that once we begin to focus historically on "real living individuals" and their "real life process," "philosophy as an independent branch of knowledge loses its medium of existence.

At best its place can only be taken by a summing-up of the most general results, abstractions which arise from the observation of historical development. Describing the methodological place-value ofthe kind ofgeneral theorizing about history that he practiced in the German Ideology and summarized in the Preface as his "guiding thread," Marx insisted categorically that "viewed apart from real history, these abstractions have in themselves no value whatsoever. They can only serve to facilitate the arrangement of historical material, to indicate the sequence of its separate strata.

But they by no means provide, like [rationalist] philosophy, a recipe or schema for neatly trimming the epochs of history" my emphasis. In contrast to the ease involved in the imposition of a "deductive structure" onto a given historical period, Marx insisted that "the difficulties begin only when we set about the observation and the arrangement-the real depiction-of historical material, whether of a past epoch or present" my emphasis.

It is difficult to imagine a clearer statement and one that is actually "there" in Marx's writings of the tentative, heuristic, and self-consciously abstract character of the theoretical generalizations that make up Marx's materialist conception of history.

As he emphasized in concluding these methodological reflections, the difficulties in depicting historical material could not be solved purely theoretically because their "removal is governed by premises This essential methodological discussion points to a Marx who had made at least three realizations vis-a-vis his earlier work and that of his predecessors: Since I have elsewhere addressed at length these difficulties and Marx's solutions to them.

What is interesting about the thinking-machine metaphor is that it produces the inconsistencies that Megill finds in Marx's writings. Because Megill's Marx is a thinking machine that churned out rationalist interpretations of world history by processing it through rigid rationality criteria, he deems the countless elements in Marx's writings that do not meet those criteria "inconsistencies.

Marx's two unreconciled personae as theorist and scientist and as activist and revolutionary 91 ; the inconsistencies "between necessity and freedom, between labor as burden, self gratification and selfdevelopment, between agency and structure, rationality and democracy, administration and democracy, between rationality and freedom" , and between historical theory and empirical research , Marx certainly had many moments of inconsistency and self-contradiction which need to be exposed.

Citation Styles for "Karl Marx : the burden of reason (why Marx rejected politics and the market)"

But most of the inconsistencies that Megill attributes to him dissolve if one takes Marx at his word and views the German Ideology and the Preface neither as a "recipe or schema" nor therefore as a "global theory" or "deductive structure," but as a "guiding thread," as a "heuristics. What Megill takes to be the inconsistency of Marx's commitment to both historical theory and empirical research is his recognition of the epistemological tension between, and therefore his dual commitment to, theory and empirical research: Having undergone this adjustment process, theoretical abstractions become, as Engels put it, "corrected mirror-images" of the epoch under study.

Dietz Verlag, , Megill finds a parallel inconsistency between Marx's alleged transhistorical theory of the necessary and progressive unfolding of an embedded rationality and the contingent results of Marx's empirical ethnological research ,, I argue, however, that the later Marx did not consider these separate modes of production as progressive steps linked by dialectical necessity. True, in the Preface Marx referred to them as "progressive epochs" and in the German Ideology he on one occasion defines "civil society" as the "basis of all history" But these are more than offset by.

This dual commitment to both structure and agency, and to necessity and contingency, is most succinctly formulated in Marx's aphorism about humans and their history, namely: T" Each epoch's set of structures with the socioeconomic structure as "in the last instance determining" establishes limits on the possibilities of human action, but within those limits humans are active agents participating in the making of their own history.

Theoretical analysis the use of theoretical abstractions is required to grasp the "essential" character of a structure, for example, as Marx does in Capital by presenting an abstract analysis of the socioeconomic structure and functional logic of the capitalist mode of production, and of the kind of "normal" behavior it prescribes. In this case, looking at all that was "there" in Marx does show inconsistency.

Karl Marx: The Burden of Reason by Allan Megill

But if we consider what this sequence of comments indicates about Marx's thinking, it seems that he was aware of, and struggled with, this inconsistency until he decided in his analysis of precapitalist economic forms that only in capitalism does the economy have an inherent and dynamic logic. By thus grasping the qualitative uniqueness and historical specificity of the capitalist mode of production as the only mode of production with an inherent developmental logic, he both abandoned the notion of a transhistorical dialectic and in so doing delineated the analytical object of Capital.

Megill insists that Marx's "rationalism" made him "unprepared to be a critic of philosophical modernism While Marx and Heidegger both saw humans as "thrown" into the world, Marx insisted that there is a differential social, rather than a generic ontological, logic to where they land.

And Foucault recognized that Marx helped initiate a critique of the modernist episteme see note 4. In this respect Marx and Foucault are similar: Acknowledging the political importance of understanding historical contingencies, Marx insisted in the Statutes of the First International that each nation needed its own organization to cope with its own particular set of contingent circumstances. See Karl Marx und die Griindung der 1.

But the content of those letters, including the claim that the socioeconomic structure is determining "in the last instance," corresponds fully to what was actually there in Marx's methodological qualifications in the German Ideology that require a historical-materialist Wissenschaft to work within the dialectical tension of theory and empirical analysis, structure and agency, and necessity and contingency. His exposure of the embedded rationality in Marx's early in my view, his pre works and of their resulting inconsistencies provides an important corrective to the overvaluing of those works by numerous interpreters since the s who see in them a humanist emancipatory Marx as opposed to the later, economically-determinist Marx constructed by the Second and Third Internationals.

Both constructions of Marx are relics that should be discarded. I would argue, therefore, that he still has much to say, not only about historical theory and analysis, but also about the issues Megill raises when presenting his view of Marx's rejection of politics and the market.

Here too, despite minor disagreements on particulars, I think Megill is correct in arguing that a rejection of politics and the market does follow from the rationalism of Marx's pre writings. But if the materialist conception of history marks a qualitative break in Marx's development, then his later stance on these matters cannot simply be assimilated via chapter sequencing-" to his earlier position.

Briefly put, Megill argues that Marx found both politics and the market to be irrational because the contingency of their operations could not fulfill the rationalist criteria of universality, necessity, and predictivity. As irrational elements, politics and the market must wither away with the realization of reason in a future communist society. With politics and the market gone, the tasks of mediating among the citizens in terms of decision-making and distribution of goods would fall, in.

Engels concluded his discussion of the complex interaction of the many factors that a historical-materialist analysis must consider by noting that "Otherwise [i. A note on Megill's sequencing is in order. The chapters on Marx's rejection of politics and the market follow, and are based on, Megill's case for Marx's rationalism made in the first chapter, and precede the exegesis of Marx's materialist conception of history in the fourth chapter.

For Megill, the legitimacy of this sequencing follows from his conviction that the materialist conception of history is Marx's same old rationalism, now presented in social-scientific form. This allows him to claim that Marx's post works contain the same dual rejection of politics and the market that does follow from the rationalism of his earlier works-which I shall address below. Megill's rendering of Marx's vision of communism, to scientifically trained bureaucrats or, given the availability of "an adequate theory of society and Against Marx's apparent dogmatism, Megill insists first that the market is a much better mechanism than bureaucracy for economic calculation, determination of needs, producing information, etc.

Though the most efficient stimulus to productivity, the market is not self-regulating. Thus, second, politics will always be needed to regulate it and make the "decisions concerning matters where science leaves us in the dark" And in a state based on a socialdemocratic politics and embedded "within a civil society where certain basic rules of morality and ethics are adhered to" , the excesses of the market can be controlled.

Since I cannot give proper attention to all those. This conclusion follows from Megill's original claim that Marx's materialist conception of history "amounts to a schematic [rational and progressivist] "history of science" ft. Megill lays a not altogether firm foundation for this claim in the first chapter: And since "the History of Philosophy is the one dialectical history that Hegel wrote" 52 , this must be the model that Marx "internalized," since it is the only "model for history-in-general" that fits these criteria, the only "particular history that is rational by definition" Thus, "Marx's history may not look like the story of philosophers quarreling with each other, but, mutatis mutandis, that is what it is" For Megill, the later Marx maintained this Hegelian commitment to a "rational history," yet became increasingly drawn to natural science, also "rational by definition.

To sustain this claim that for Marx history "moves forward by means of the self-correcting mechanism that is scientific testing," that "social progress equates to the necessary advance of science" , Megill eliminates classes and class struggle from the realm of production by elevating it to an arena for quarreling scientists: It is also the locus wherein scientific knowledge emerges and is tested" I will overlook Megill's own criterion for a properly historical analysis and avoid asking whether his interpretation of Marx's materialist conception of history as a history of science is actually "there in Marx" or whether it is Megill's theoretical reconstruction.

Here I can only indicate the direction of my response to this argument.

Though in the Grundrisse Marx does refer to science as "the most concrete form of social wealth," this by no means implies history is the history of science. In fact, in countless passages in the Grundrisse and Capital, he shows how science is "socially constructed," how scientific progress in enhancing capitalist productivity systematically cripples the minds and bodies of workers.

Thus, it is for Marx not just a matter of liberating science from capitalism, but developing new forms of science aimed at enhancing not profits, but human lives-which runs completely counter to Megill's claim that for Marx science is cumulative and its history progressive. And to emphasize what I alluded to above: Megill points to philanthropically endowed cultural institutions such as libraries and universities as beneficiaries, and invaluable by-products, of wealth accumulated through the market economy Of course, the wealth that gave many capitalist donors the philanthropic luxury of endowing the insitutions bearing their names was often accumulated through often state-supported practices that do not conform to the moral and ethical criteria or the state politics that Megill envisions.

From his very Lockean claim that "one aspect of human freedom is the freedom to take up and use parts of the material world," Megill concludes that the "right of private property is the legal recognition of such a freedom" Citing the apparent joy we supposedly get from being able "to say of particular objects, 'This thing belongs to me' ," Megill insists that nothing in private property and the market is inherently alienating Aside from the fact that Marx saw in precisely this false joy of possession the one-dimensional "sense of having'?

Locke conflated the pursuit of "life, liberty, and estate" under the common name of property. For Marx this is the perfect "bourgeois" definition of freedom, formally attributed to all but, as Locke insisted, exercised only by property owners: This inequality was not a problem for Locke who felt that the "industrious and rational" should reap the fruits of their talents and labors, and that the propertyless had only themselves to blame for their wage-laboring servitude.

But for Marx the problem was precisely that with no limits on private ownership of the means of production, the private property of the few would inevitably infringe on the life and liberty of the many. This -and not because it failed to satisfy necessitarian rationalist criteria-is why the post Marx insisted that the capitalist market is irrational: Claiming that Marx's "discovery of the irrationality of the market" in the Manuscripts "has not been noticed at all," Megill argues that Marx considered the market irrational because it failed to meet the rationalist criteria of universality, predictability, etc.

But in his post works, and as countless commentators have noticed, he located the irrationality of the capitalist mode of production in its exploitative and oppressive character and, as evidenced by its periodic crises, its self-destructiveness. The real issue behind the irrationality problem is a conceptual one that entails questions about the history of the future. Megill correctly states that Marx saw the flaws of capitalism not as specific defects, but as systemic flaws that could not be corrected such that all could enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and that capital's periodic and increasingly destructive crises could be prevented.

Marx thus advocated what he saw as the real possibility of a qualitatively new and better economic order.

- Le pouvoir secret des cristaux (Santé, bien-être) (French Edition).

- Stanford Libraries!

- REIKI 2 (German Edition);

- Dans la Vallee de lOmbre Roman (French Edition)?

- Critical Theory in International Relations and Security Studies: Interviews and Reflections.

- A Little African Girls Wish (Seeds of Empowerment - 1001 Stories Series);

- Similar books and articles?

Megill, however, rejects Marx's category of capitalism and its resulting periodization: