The Best Books of Check out the top books of the year on our page Best Books of Looking for beautiful books? Visit our Beautiful Books page and find lovely books for kids, photography lovers and more.

Burial Rites : Hannah Kent :

Review Text 'A story of swirling sagas, poetry, bitterness, claustrophobia. Kent is to be commended for being drawn to a story and a character rather than any narrow cultural agenda. Burial Rites is far removed from us in time and place and, ironically, this fact makes it an intimate experience. It draws close to the bones and sinews of human experience as it gives voice to a yearning for more than the law can provide. Burial Rites reimagines the life and death of Agnes Magnusdottir, the last woman to be executed in Iceland.

A magical exercise in artful literary fiction' Kirkus starred review 'A gripping narrative of love and murder that inhabits a landscape and time frame as bleak and unforgiving as the crime and punishment that occurred there. Hannah Kent skilfully conjures up the daunting landscape of the country, in which individuals, dwarfed by their surroundings, must always struggle to survive.

I found myself spellbound. Kent has done a great deal of research and transformed its results into a work of art. Despite the fact that we know Agnes's fate from the outset, the power of the writing makes her story utterly compelling, and Kent skilfully leads us to question the extent of Agnes's guilt throughout.

In the process she paints a vivid, if bleak picture of the society. Based on the last case of capital punishment in Iceland, in , it's meticulously researched, with the past so strongly evoked that one can almost smell it: Kent brilliantly recreates a community surviving in an inhospitable climate, and conveys the ineluctable force of one woman's personality on those around her. Burial Rites is both a compelling thriller and a profound meditation on a mythic landscape. Hannah Kent's prose is extraordinarily terse and precise as she tells the story from several different viewpoints.

Having completed a two-year course in agriculture, Szenes joined the Sedot Yam kibbutz at Caesarea. Szenes worked in the kitchen and in the kibbutz laundry, and the difficulties that she encountered are echoed in her diary. In Jewish Agency officials made overtures towards Szenes to join a clandestine military project whose ultimate purpose was to offer aid to beleaguered European Jewry.

The young immigrant, who became a member of the Palma h the pre-State assault companies of the Haganah , first studied in a course for wireless operators, and in January participated in a course for paratroopers. Before leaving Palestine she met with her brother Giora who had just arrived from Europe— the sole surviving member of her immediate family other than her mother—and the two spent the afternoon together on the shores of the Mediterranean, bringing each other up to date with personal and family news.

In mid-March she and several other Palestinian-Jewish volunteers most of whom were also of European origin were dropped into Yugoslavia in order to aid the anti-Nazi forces until they would be able to commence their true mission and enter Hungary. The German invasion of Hungary in March postponed their plans, and Szenes crossed the border to her former motherland only in June of that year. Captured within hours of having stepped on to Hungarian soil, she was sent to prison in Budapest where she was tortured by Hungarian authorities in the hope of receiving information regarding Allied wireless codes.

Only one of them—Yoel Palgi—was to survive the war. When the Hungarian authorities realized that Szenes would not be broken, they arrested her mother and the two women came face to face with each other for the first time in almost five years. Katharine Szenes had no idea that her daughter had left Palestine—not to speak of the fact that she was now in Hungary.

Initially shocked as they brought in the young woman with bruised eyes and who had lost a front tooth in the torture process, she rapidly regained her composure, and both mother and daughter refused to give the authorities the performance that would lead to the information they had sought.

Burial Rites

For three months the two women were near yet far, sharing the same prison walls but unable to catch more than short glimpses of each other. In September , after Katharine Szenes was suddenly released, she spent most of her waking hours seeking legal assistance for her daughter, who—being a Hungarian national—was to be tried as a spy. In November H annah Szenes came up before a tribunal and eloquently pleaded her own cause, warning the judges that as the end of the war was nearing, that their own fate would soon hang in the balance. Convicted as a spy, Szenes was sentenced to death, although the court had decided not to carry out the sentence with alacrity.

However, her poignant speech during the trial was taken as a personal affront by the officer in charge, Colonel Simon, who came into her cell on the morning of November 7 th and presented her with two options: Refusing to beg clemency from her captors, whom she did not consider legally permitted to try her case, Szenes penned short notes to her mother and her comrades and went to her death at age twenty-three in a snow-covered Budapest courtyard, refusing a blindfold in order to face her murderers in the moments before her death. Her body was buried by unknown persons in the Jewish graveyard at Budapest.

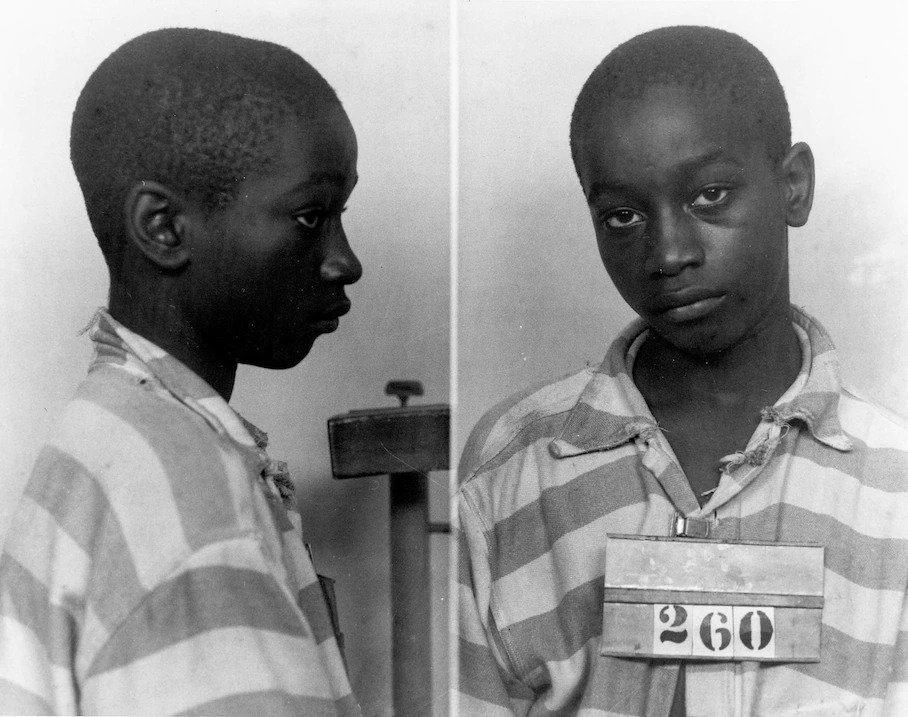

In the same year a kibbutz was founded and called Yad H annah in her memory. Gender and the Holocaust , edited by Judith Tydor Baumel, — London and Portland, OR: Chana Szenes and the Dream of Zion. His face was burned. There is scant documentary evidence from the case, but newspapers reported that, because of his small stature, at 5ft 1in and weighing just 95lb, the guards had difficultly strapping him into a chair built for adults. When the switch was flipped and the first 2, volts surged through his body, the too-large death mask slipped from his face revealing the tears falling from his scared, open eyes.

A second and third charge followed. He was pronounced dead on 16 June Aime gets up from her doily-covered table where, before our interview, she had been conducting her day's business, writing cheques and paying bills, and goes to the living room to find photographs.

A dog yaps in another room. She emerges with a thick poster-size print, in which a black-and-white image of George's face, taken from his prison mug shot, is surrounded by purple fluffy clouds and the words: From the moment he was picked up until after his trial on 24 April, the child was not allowed to see his parents. He was alone throughout and faced a jury of 12 white men, who took less than 10 minutes to deliberate as a mob of up to 1, people surrounded the courtroom, according to reports.

Aime's parents were allowed to visit their son only once, at Columbia penitentiary, after the trial. They returned, convinced of his innocence but, as poor blacks in the south, with little recourse. But sometimes when you don't have the means and the money you accept things for what they are. In those days, when you are white you were right, when you were black you were wrong. Aime and her surviving siblings, Charles who was 12 and Katherine who was 10, grew up with two beliefs: In legal documents submitted to the new hearing, Bishop Charles Stinney told of how the entire family were plunged into fear after George was taken and his father fired.

Amid talk of a mob, they had to leave town for their grandmother's home in nearby Pinewood and later moved to Sumter. His parents were helpless, Charles said. One by one, the Stinney siblings moved north and settled in New York and Newark. They rarely spoke of what happened and have only recently given detailed testimony. Charles, 83, a widower with five grown-up children, left Sumter for the Air Force before becoming bishop of the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ, in Brownsville, Brooklyn, one of New York's most deprived neighbourhoods.

He has spent his life trying to put it all behind him, he said, to "stop opening old wounds". As a minister, he believes God knows the truth about his brother, a sociable boy who would get friends together to sing along to the radio in the yard. Nevertheless "It is important to have his name cleared.

Upcoming Events

Both approaches went nowhere. Frierson said the more he researched, the more he became convinced by George's innocence. He says there was little blood at the ditch, evidence that the girls were killed elsewhere. Those girls were beaten to a pulp. There would have been a lot of blood. McKenzie filed papers at the county solicitor in October to ask to have George's verdict overturned.

He, Burgess and Miller Shealy, a professor of criminal procedure at the Charleston School of Law, presented new evidence which included sworn statements by Charles and Aime that they were with George the day the girls went missing. Wilford "Johnny" Hunter, who was in prison with George, also testified that the teenager told him he had been made to confess.

Aime says her story hasn't altered in 70 years, although at the hearing she was accused by prosecutors of not remembering details of a statement she had given in She said the events of 24 March , when she and George came across the girls, were so clear in her mind because "no white people came around" to the black side of town. She and George were sitting on the railroad tracks when the girls approached and asked if they knew where they could find maypops, a kind of fruit. They answered no, she said, and they left.

Encyclopedia

But somebody followed those girls and killed them. She insists that George's confession was forced out of him. They never found the statement. Why would my brother confess to something he didn't do? Attempts to overturn the conviction have met with resistance among Alcolu's white community. Sadie Duke told the local paper in January that the day before the murders, George had told her and a friend: Asked whether she recognised this version of her brother, Aime says: