For one thing, the diner's plate-glass windows cause far more light to spill out onto the sidewalk and the brownstones on the far side of the street than is true in any of his other paintings. As well, this interior light comes from more than a single lightbulb, with the result that multiple shadows are cast, and some spots are brighter than others as a consequence of being lit from more than one angle. Across the street, the line of shadow caused by the upper edge of the diner window is clearly visible towards the top of the painting.

These windows, and the ones below them as well, are partly lit by an unseen streetlight, which projects its own mix of light and shadow.

As a final note, the bright interior light causes some of the surfaces within the diner to be reflective. This is clearest in the case of the right-hand edge of the rear window, which reflects a vertical yellow band of interior wall, but fainter reflections can also be made out, in the counter-top, of three of the diner's occupants. None of these reflections would be visible in daylight.

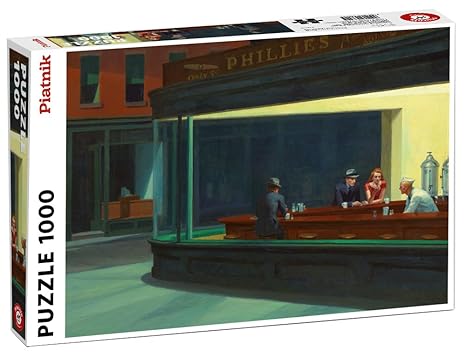

Nighthawks, 1942 by Edward Hopper

The similarity in lighting and themes makes this possible; it is certainly very unlikely that Hopper would have failed to see the exhibition, and as Levin notes, the painting had twice been exhibited in the company of Hopper's own works. Although there is no evidence at all other than the fact that Hopper admired the story , Levin also suggests that he may have been inspired by Ernest Hemingway 's short story, The Killers.

Toggle navigation Edward Hopper. Rooms by the Sea. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery. Aug 9, 2: Edward Hopper, Nighthawks , Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Navigation menu

For an image so often associated with loneliness, Edward Hopper. Accordingly, his compositions render a psychological portrait of an elusive and introspective artist, even as they depict imagined scenes. Indeed, many of his works illustrate troubled romantic relationships. In painting after painting, despondent couples share the same space, even as they seem to exist in entirely different worlds.

A reclusive teenager finds his voice. Edward Hopper SelfPortrait , He was born in the town of Nyack in , the second of two children in a middle-class Baptist family of Dutch descent. His father, Garrett, who ran a local shop and struggled to keep it afloat, was a lover of literature.

His mother, Elizabeth, was an art enthusiast. A tall, gangly, and shy teenager, Hopper took refuge in reading and drawing, even poking fun at his awkward physique in some illustrations. But his ability as an artist also fostered lofty career ambitions. A brief stint in illustration school followed. It was an experience, Gail Levin writes in Edward Hopper: Very good looking blond boy in white coat, cap inside counter.

Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk beak in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt clean holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back--at left. Light side walk outside pale greenish. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant, dark--Phillies 5c cigar.

Outside of shop dark, green.

Nighthawks, by Edward Hopper

In January , Jo confirmed her preference for the name. In a letter to Edward's sister Marion she wrote, "Ed has just finished a very fine picture--a lunch counter at night with 3 figures. Night Hawks would be a fine name for it. He was about a month and half working on it. Upon completing the canvas in the late winter of , Hopper placed it on display at Rehn's, the gallery at which his paintings were normally placed for sale.

It remained there for about a month. Barr spoke enthusiastically of Gas , which Hopper had painted a year earlier, and "Jo told him he just had to go to Rehn's to see Nighthawks. In the event it was Rich who went, pronounced Nighthawks 'fine as a Homer ', and soon arranged its purchase for Chicago. The painting has remained in the collection of the Art Institute ever since. The scene was supposedly inspired by a diner since demolished in Greenwich Village , Hopper's neighborhood in Manhattan.

Hopper himself said the painting "was suggested by a restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet. This reference has led Hopper aficionados to engage in a search for the location of the original diner.

The inspiration for this search has been summed up on the blog of one of these searchers: The spot usually associated with the former location is a now-vacant lot known as Mulry Square at the intersection of Seventh Avenue South, Greenwich Avenue and West 11th Street, about seven blocks west of Hopper's studio on Washington Square. However, according to an article by Jeremiah Moss in The New York Times , this cannot be the location of the diner that inspired the painting as a gas station occupied that lot from the s to the s.

Moss located a land-use map in a s municipal atlas showing that "Sometime between the late '30s and early '50s, a new diner appeared near Mulry Square. Moss comes to the conclusion that Hopper should be taken at his word: Moss concludes, "the ultimate truth remains bitterly out of reach. Because it is so widely recognized, the diner scene in Nighthawks has served as the model for many homages and parodies. Hopper influenced the Photorealists of the late s and early s, including Ralph Goings , who evoked Nighthawks in several paintings of diners. Richard Estes painted a corner store in People's Flowers , but in daylight, with the shop's large window reflecting the street and sky.

Nighthawks

More direct visual quotations began to appear in the s. Several writers have explored how the customers in Nighthawks came to be in a diner at night, or what will happen next. Wolf Wondratschek 's poem "Nighthawks: After Edward Hopper's Painting" imagines the man and woman sitting together in the diner as an estranged couple: