Within Christian studies the concept of revival is derived from biblical narratives of national decline and restoration during the history of the Israelites. In particular, narrative accounts of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah emphasise periods of national decline and revival associated with the rule of various righteous and wicked kings. Josiah is notable within this biblical narrative as a figure who reinstituted temple worship of Yahweh while destroying pagan worship.

Within modern Church history, church historians have identified and debated the effects of various national revivals within the history of the USA and other countries. During the 18th and 19th centuries American society experienced a number of " Awakenings " around the years , , , and The Bible narrative records a number of revivals within the history of the Israelites. In particular, following the development of temple worship based in Jerusalem the Bible records periods of national decline and revival associated with the rule of righteous and wicked kings.

Within this historical narrative the reign of Josiah epitomises the effect of revival on Israelite society in reinstituting temple worship of Yahweh and the rejection of pagan worship and idolatry. Other Jewish narratives such as the accounts of the Maccabean revolt in like manner record national revival characterised by the rejection of pagan worship practices and the military defeat and expulsion of idolatrous foreign powers. Many Christian revivals drew inspiration from the missionary work of early monks, from the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Reformation and from the uncompromising stance of the Covenanters in 17th-century Scotland and Ulster, that came to Virginia and Pennsylvania with Presbyterians and other non-conformists.

Its character formed part of the mental framework that led to the American War of Independence and the Civil War. The 18th century Age of Enlightenment had two camps: A similar but smaller scale revival in Scotland took place at Cambuslang , then a village and is known as the Cambuslang Work.

In the American colonies the First Great Awakening was a wave of religious enthusiasm among Protestants that swept the American colonies in the s and s, leaving a permanent impact on American religion. It resulted from powerful preaching that deeply affected listeners already church members with a deep sense of personal guilt and salvation by Christ. Pulling away from ancient ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made religion intensely emotive to the average person by creating a deep sense of spiritual guilt and redemption. Ahlstrom sees it as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval" that also created Pietism in Germany, the Evangelical Revival and Methodism in England.

It incited rancor and division between the traditionalists who argued for ritual and doctrine and the revivalists who ignored or sometimes avidly contradicted doctrine, e. Its democratic features had a major impact in shaping the Congregational , Presbyterian , Dutch Reformed , and German Reformed denominations, and strengthened the small Baptist and Methodist denominations. It had little impact on Anglicans and Quakers. Unlike the Second Great Awakening that began about and which reached out to the unchurched , the First Great Awakening focused on people who were already church members.

It changed their rituals, their piety, and their self-awareness. The Hungarian Baptist church sprung out of revival with the perceived liberalism of the Hungarian reformed church during the late s. Many thousands of people were baptized in a revival that was led primarily by uneducated laymen, the so-called "peasant prophets". During the 18th century, England saw a series of Methodist revivalist campaigns that stressed the tenets of faith set forth by John Wesley and that were conducted in accordance with a careful strategy.

In addition to stressing the evangelist combination of "Bible, cross, conversion, and activism," the revivalist movement of the 19th century made efforts toward a universal appeal — rich and poor, urban and rural, and men and women. Special efforts were made to attract children and to generate literature to spread the revivalist message.

Some historians, such as Robert Wearmouth, suggest that evangelical revivalism directed working-class attention toward moral regeneration, not social radicalism. Thompson , claim that Methodism, though a small movement, had a politically regressive effect on efforts for reform. Eric Hobsbawm claims that Methodism was not a large enough movement to have been able to prevent revolution.

Alan Gilbert suggests that Methodism's supposed antiradicalism has been misunderstood by historians, suggesting that it was seen as a socially deviant movement and the majority of Methodists were moderate radicals. Early in the 19th century the Scottish minister Thomas Chalmers had an important influence on the evangelical revival movement. Chalmers began life as a moderate in the Church of Scotland and an opponent of evangelicalism.

During the winter of —04, he presented a series of lectures that outlined a reconciliation of the apparent incompatibility between the Genesis account of creation and the findings of the developing science of geology. However, by he had become an evangelical and would eventually lead the Disruption of that resulted in the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. The Plymouth Brethren started with John Nelson Darby at this time, a result of disillusionment with denominationalism and clerical hierarchy.

The established churches too, were influenced by the evangelical revival. However its objective was to renew the Church of England by reviving certain Roman Catholic doctrines and rituals, thus distancing themselves as far as possible from evangelical enthusiasm. Many say that Australia has never been visited by a genuine religious revival as in other countries, but that is not entirely true. The effect of the Great Awakening of was also felt in Australia fostered mainly by the Methodist Church, one of the greatest forces for evangelism and missions the world has ever seen.

Evangelical fervor was its height during the s with visiting evangelists, R. Alexander and others winning many converts in their Crusades. Evangelicalism arrived from Britain as an already mature movement characterized by commonly shared attitudes toward doctrine, spiritual life, and sacred history.

Any attempt to periodize the history of the movement in Australia should examine the role of revivalism and the oscillations between emphases on personal holiness and social concerns. Historians have examined the revival movements in Scandinavia, with special attention to the growth of organizations, church history, missionary history, social class and religion, women in religious movements, religious geography, the lay movements as counter culture, ethnology, and social force.

Some historians approach it as a cult process since the revivalist movements tend to rise and fall. Others study it as minority discontent with the status quo or, after the revivalists gain wide acceptance, as a majority that tends to impose its own standards. Charles Finney — was a key leader of the evangelical revival movement in America. From onwards he conducted revival meetings across many north-eastern states and won many converts.

For him, a revival was not a miracle but a change of mindset that was ultimately a matter for the individual's free will. His revival meetings created anxiety in a penitent's mind that one could only save his or her soul by submission to the will of God, as illustrated by Finney's quotations from the Bible. Finney also conducted revival meetings in England, first in and later to England and Scotland in — In New England , the renewed interest in religion inspired a wave of social activism, including abolitionism.

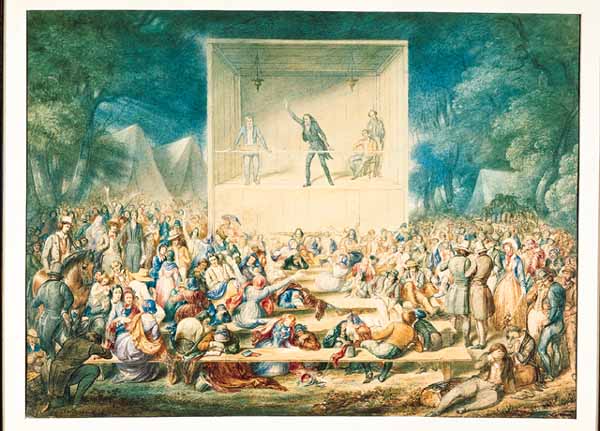

It had been here, in upstate New York 's ' Burned-over district ,' in the s and 20s, that the religious fervor acquired a fevered pitch, and this intense revivalism spawned an authentically new American sect — which ultimately would become a major worldwide religion — Mormonism , founded by a young seeker of Christian primitivism , Joseph Smith, Jr It also introduced into America a new form of religious expression—the Scottish camp meeting. In German-speaking Europe Lutheran Johann Georg Hamann — 88 was a leading light in the new wave of evangelicalism, the Erweckung , which spread across the land, cross-fertilizing with British movements.

The movement began in the Francophone world in connection with a circle of pastors and seminarians at French-speaking Protestant theological seminaries in Geneva , Switzerland and Montauban , France, influenced inter alia by the visit of Scottish Christian Robert Haldane in — Several missionary societies were founded to support this work, such as the British-based Continental society and the indigenous Geneva Evangelical Society.

As well as supporting existing Protestant denominations, in France and Germany the movement led to the creation of Free Evangelical Church groupings: The movement was politically influential and actively involved in improving society, and — at the end of the 19th century — brought about anti-revolutionary and Christian historical parties. At the same time in Britain figures such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Chalmers were active, although they are not considered to be part of the Le Reveil movement. Significant names include Dwight L. Moody , Ira D. He brought in the converts by the score, most notably in the revivals in Canada West His technique combined restrained emotionalism with a clear call for personal commitment, coupled with follow-up action to organize support from converts.

It was a time when the Holiness Movement caught fire, with the revitalized interest of men and women in Christian perfection. Caughey successfully bridged the gap between the style of earlier camp meetings and the needs of more sophisticated Methodist congregations in the emerging cities. In England the Keswick Convention movement began out of the British Holiness movement , encouraging a lifestyle of holiness , unity and prayer. Prove to me that any thing that takes the name of a revival is really spurious, and I pledge myself as a friend of true revivals, to be found on the list of its opposers.

Things, facts, realities, are every thing. Another objection to revivals closely allied to the preceding is, that the subjects of them often fall into a state of mental derangement, and even commit suicide. The fact implied in this objection is, to a certain extent, acknowledged; that is, it is acknowledged that instances of the kind mentioned do sometimes occur.

But is it fair, after all, to consider revivals as responsible for them? Every one who has any knowledge of the human constitution, must be aware that the mind is liable to derangement from any cause that operates in the way of great excitement; and whether this effect in any given case, is to be produced or not, depends partly on the peculiar character of the mind which is the subject of the operation, and partly on the degree of self-control which the individual is enabled to exercise.

Hence we find on the list of maniacs, and of those who have committed suicide, many in respect to whom this awful calamity is to be traced to the love of the world. Their plans for accumulating wealth have been blasted, and when they expected to be rich they have suddenly found themselves in poverty and perhaps obscurity; and instead of sustaining themselves against the shock, they have yielded to it; and the consequence has been the wreck of their intellect, and the sacrifice of their life.

You who are men of business well know that the case to which I have here referred is one of no uncommon occurrence; but who of you ever thought that these cases reflected at all upon the fair and honorable pursuit of the world? Here you are careful enough to distinguish between the thing, and the abuse of it; and why not be equally candid in respect to revivals of religion? When you hear of instances of suicide in revivals, remember that such instances occur in other scenes of life, and other departments of action; and if you are not prepared to make commerce, and learning, and politics, and virtuous attachment, responsible for this awful calamity, because it is sometimes connected with them, then do not attempt to cast this responsibility upon religion, or revivals of religion, because here too individuals are sometimes left to this most fearful visitation.

I have said that some such cases as the objection supposes occur; but I maintain that the number is, by the enemies of revivals, greatly overrated. Twenty men may become insane, and may actually commit suicide from any other cause, and the fact will barely be noticed; but let one come to this awful end in consequence of religious excitement, and it will be blazoned upon the house top, with an air of melancholy boding and yet with a feeling of real triumph; and many a gazette will introduce it with some sneering comments on religious fanaticism; and the result will be that it will become a subject of general notoriety and conversation.

In this way, the number of these melancholy cases comes to be imagined much larger than it really is; and in the common estimate of the opposers of revivals, it is no doubt multiplied many fold.

- ;

- .

- Proof of the Existence of God.

- 30 Ways To Lower Blood Pressure Naturally - A Step By Step Plan To Reduce Blood Pressure Quickly!

- Oliver Goldsmith: The Critical Heritage: Volume 42 (The Collected Critical Heritage : 18th Century Literature).

- revivalism.

But admitting that the number of these cases were as great as its enemies would represent—admit that in every extensive revival there were one person who actually became deranged, and fell a victim to that derangement, are you prepared to say, even then, upon an honest estimate of the comparative good and evil that is accomplished, that that revival had better not have taken place? On the one side, estimate fairly the evil; and we have no wish to make it less than it really is.

There is the premature death of an individual;—death in the most unnatural and shocking form; and fitted to harrow the feelings of friends to the utmost. There may be a temporary loss of usefulness to the world; and as the case may be, a loss of counsel, and aid, and effort, in some of the tenderest earthly relations. Yet it is not certain but that the soul may be saved: But suppose the very worst—suppose this sinner who falls in a fit of religious insanity, by the violence of his own hand, to be unrenewed—why in this case he rushes prematurely upon the wrath of God; he cuts short the period of his probation; which, had it been protracted, he might or might not, have improved to the salvation of his soul.

Look now at the other side. In the revival in which this unhappy case has occurred, besides the general quickening impulse that has been given to the people of God, perhaps one hundred individuals have had their character renovated, and their doom reversed. Each one of these was hastening forward perhaps to a death bed of horror, certainly to an eternity of wailing; but in consequence of the change that has passed upon them, they can now anticipate the close of life with peace, and the ages of eternity with unutterable joy.

There is no longer any condemnation to them, because they are in Christ Jesus. And besides, they are prepared to live usefully in the world;—each of them to glorify God by devoting himself, according to his ability, to the advancement of his cause. Now far be it from us to speak lightly of such a heart-rending event as time death of a fellow-mortal, in the circumstances we have supposed; but if any will weigh this against the advantages of a revival, we have a right to weigh the advantages of a revival against this; and to call upon you to decide for yourselves which preponderates?

Is the salvation of one hundred immortal souls supposing that number to be converted a light matter, when put into the scale against the premature and awful death of a single individual; or to suppose the very worst of the case—his cutting short his space for repentance, and rushing unprepared into the presence of his Judge?

It is further, objected against revivals, that they occasion a sort of religious dissipation; leading men to neglect their worldly concerns for too many religious exercises; exercises too, protracted, not unfrequently, to an unseasonable hour. No doubt it is possible for men to devote themselves more to social religious services than is best for their spiritual interests; because a constant attendance on these services would interfere with the more private means of grace, which all must admit are of primary importance.

But who are the persons by whom this objection is most frequently urged, and who seem to feel the weight of it most strongly?

Or are they not rather those who rarely, if ever, retire to commune with God, and who engage in the business of life from mere selfish considerations;—who, in short, are thorough going worldlings? If a multitude of religious meetings are to be censured on the ground of their interference with other duties, I submit it to you whether this censure comes with a better grace from him who performs these duties, or from him who neglects them?

I submit it to you, whether the man who is conscious of living in the entire neglect of religion, ought to be very lavish in his censures upon those who are yielding their thoughts to it in any way, or to any extent?

Would it not be more consistent at least for him to take care of the beam, before he troubles himself about the mote? Far be it from me to deny that the evil which this objection contemplates does sometimes exist;— that men, and especially women, do neglect private and domestic duties for the sake of mingling continually in social religious exercises: For I ask who are the persons who have ordinarily the best regulated families, who are most faithful to their children, most faithful in their closets, most faithful and conscientious in their relative duties, and even in their worldly engagements?

If I may be permitted to answer, I should say unhesitatingly, they are generally the very persons, who love the social prayer meeting, and the meeting for Christian instruction and exhortation; those in short who are often referred to by the enemies of revivals, as exemplifying the evil which this objection contemplates. God requires us to do every duty, whether secular or religious, in its right place; and this the Christian is bound to keep in view in all his conduct.

But there is too much reason to fear that the spirit which ordinarily objects against many religious exercises, is a spirit, which, if the whole truth were known, it would appear, had little complacency in any. But it is alleged that, during revivals, religious meetings are not only multiplied to an improper extent, but are protracted to an unseasonable hour.

That instances of this kind exist admits not of question; and it is equally certain that the case here contemplated is an evil which every sober, judicious Christian must discourage. We do not believe that in an enlightened community, it is an evil of very frequent occurrence; but wherever it exists, it is to be reprobated as an abuse, and not to be regarded as any part of a genuine revival; or as any thing for which a true revival is responsible.

But here again, it may be worth while to inquire how far many of the individuals who offer this objection are consistent with themselves. They can be present at a political cabal, or at a convivial meeting, which lasts the whole night, and these occasions may be of very frequent occurrence, and yet it may never occur to them that they are keeping unseasonable hours. Or their children may return at the dawn of day, from a scene of vain amusement, in which they have brought on an entire prostration both of mind and body, and unfitted themselves for any useful exertion during the day; and yet all this is not only connived at as excusable, but smiled upon as commendable.

I do not say that it is right to keep up a religious meeting during the hours that Providence has allotted to repose: I believe fully that in ordinary cases it is wrong; but sure I am that I could not hold up my head to say this, if I were accustomed to look with indulgence on those other scenes of the night of which I have spoken.

It is best to spend the night as God designed it should be spent, in refreshing our faculties by sleep; but if any other way is to be chosen, judge ye whether they are wisest, who deprive themselves of repose in an idle round of diversion, or they who subject themselves to the same sacrifice in exercises of devotion and piety. It is objected against revivals that they often introduce discord into families, and disturb the general peace of society.

It must be conceded that rash and intemperate measures have sometimes been adopted in connection with revivals, or at least what have passed under the name of revivals, which have been deservedly the subject of censure, and which were adapted, by stirring up the worst passions of the heart, to introduce a spirit of fierce contention and discord. But I must be permitted to say that, whatever evil such measures may bring in their train, is not to be charged upon genuine revivals of religion. The revivals for which we plead are characterized, not by a spirit of rash and unhallowed attack on the part of their friends, which might be supposed to have come up from the world below, but by that wisdom which cometh down from above; which is pure, peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated.

For all the discord and mischief that result from measures designed to awaken opposition and provoke the bad passions, they only are to be held responsible by whom those measures are devised or adopted. We hesitate not to say that there is no communion between the spirit that dictates them, and the spirit of true revivals. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that there are instances, in which a revival of religion conducted in a prudent and scriptural manner, awakens bitter hostility, and sometimes occasions, for the time, much domestic unhappiness.

There are cases in which the enmity of the heart is so deep and bitter, that a bare knowledge of the fact that sinners around are beginning to inquire, will draw forth a torrent of reproach and railing; and there are cases too in which the fact that an individual in a family becomes professedly pious, will throw that family into a violent commotion, and waken up against the individual bitter prejudices, and possibly be instrumental of exiling a child, or a wife, or a sister, from the affections of those most dear to them.

But you surely will not make religion, or a revival of religion, responsible for cases of this kind. Did not the benevolent Jesus himself say that he came not to send peace on the earth but a sword;—meaning by it this very thing—that in prosecuting the object of his mission into the world, he should necessarily provoke the enmity of the human heart, and thus that enmity would act itself out in the persecution of himself and his followers?

The Saviour, by his perfect innocence, his divine holiness, his uncompromising faithfulness, provoked the Jews to imbrue their hands in his blood; but who ever supposed that the responsibility of their murderous act rested upon him? In like manner, ministers and Christians, by laboring for the promotion of a revival of religion, may be the occasion of fierce opposition to the cause of truth and holiness; but if they labor only in the manner which God has prescribed, they are in no way accountable for that opposition.

It will always be right for individuals to secure the salvation of their own souls, let it involve whatever domestic inconvenience, or whatever worldly sacrifice it may. Where such opposition is excited, the opposers of religion may set it to the account of revivals; but God the righteous Judge will take care that it is charged where it fairly belongs. It is objected, again, to revivals that the supposed conversions that occur in them are usually too sudden to be genuine; and that the excitement which prevails at such a time, must be a fruitful source of self-deception.

That revivals are often perverted to minister to self-deception cannot be questioned; and this is always to be expected, when there is much of human machinery introduced. Men often suppose themselves converted, and actually pass as converts, merely from some impulse of the imagination, when they have not even been the subjects of true conviction.

But notwithstanding this abuse, who will say that the Bible does not warrant us to expect sudden conversions? What say you of the three thousand who were converted on the day of pentecost? Shall I be told that there was a miraculous agency concerned in producing that wonderful result? I answer there was indeed a miracle wrought in connection with that occasion; but there was no greater miracle in the actual conversion of those sinners than there is in the conversion of any other sinners; for conversion is in all cases the same work; and accomplished by the same agency—viz, the special agency of the Holy Spirit.

This instance then is entirely to our purpose; and proves at least the possibility that a conversion may be sound, though it be sudden. Nor is there any thing in the nature of the case that should lead us to a different conclusion. For what is conversion? It is a turning from sin to holiness. The truth of God is presented before the mind, and this truth is cordially and practically believed; it is received into the understanding, and through that reaches the heart and life.

Suppose the truth to be held up before the mind already awake to its importance, and in a sense prepared for its reception, what hinders but that it should be received immediately? But this would be all that is intended by a sudden conversion. Indeed we all admit that the act of conversion, whenever it takes place, is sudden; and why may not the preparation for it, in many instances, be so also?

Finney - What a Revival of Religion Is

Where is the absurdity of supposing that a sinner may, within a very short period, be brought practically to believe both the truth that awakens the conscience, and that which converts the soul;—in other words may pass from a state of absolute carelessness to reconciliation with God? The evidence of conversion must indeed be gradual, and must develope itself in a subsequent course of exercises and acts; so that it were rash to pronounce any individual in such circumstances a true convert; but not only the act of conversion but the immediate preparation for it, may be sudden; and we may reasonably hope, in any given case of apparent conversion, that the change is genuine.

I may add that the general spirit of the Bible is, by no means, unfavorable to sudden conversions. The Bible calls upon men to repent; to believe; to turn to the Lord now; it does not direct them to put themselves on a course of preparation for doing this at some future time; but it allows no delay; it proclaims that now is the accepted time, now the day of salvation. When men are converted suddenly, is there any thing more than an immediate compliance with these divine requisitions which are scattered throughout the Bible? But what is the testimony of facts on this subject?

It were in vain to deny that some who seem to be converted during the most genuine revivals fall away; and it were equally vain to deny that some who profess to have become reconciled to God, when there is no revival, fall away. But that any considerable proportion of the professed subjects of well regulated revivals apostatize, especially after having made a public profession, is a position which I am persuaded cannot be sustained. I know there are individual exceptions from this remark; exceptions which have occurred under peculiar circumstances; but if I mistake not, those ministers who have had the most experience on this subject, will testify that a very large proportion of those whom they have known professedly beginning the Christian life during a revival, have held on their way stronger and stronger.

It has even been remarked by a minister who has probably been more conversant with genuine revivals than any other of the age, that his experience has justified the remark, that there is a smaller proportion of apostacies among the professed subjects of revivals than among those who make a profession when there is no unusual attention to religion.

After all, we are willing to admit that the excitement attending a revival may be the means of self-deception. But we maintain that this is not, at least to any great extent, a necessary evil, and that it may ordinarily be prevented by suitable watchfulness and caution on the part of those who are active in conducting the work.

But with these qualifications, whether in a minister or in private Christians and with the diligent and faithful discharge of duty, we believe that little more is to be apprehended in respect to self-deception during a revival, than might reasonably be in ordinary circumstances. It is objected that revivals are followed by seasons of corresponding declension; and that, therefore, nothing is gained, on the whole, to the cause of religion. This remark must of course be limited in its application to those who were before Christians;— for it surely cannot mean that those who are really converted during a revival, lose the principle of religion from their hearts, after it has passed away.

Suppose then it be admitted that Christians, on the whole, gain no advantage from revivals, on account of the reaction that takes place in their experience; still there is the gain of a great number of genuine conversions; and this is clear gain from the world. Is it not immense gain to the church, immense gain to the Saviour, that a multitude of souls should yield up their rebellion, and become the subjects of renewing grace?

And if this is an effect of revivals and who can deny it? But it is not true that revivals are of no advantage to Christians. It is confidently believed, if you could hear the experience of those who have labored in them most faithfully and most successfully, you would learn that these were the seasons in which they made their brightest and largest attainments in religion. And these seasons they have not failed subsequently to connect with special praise and thanksgiving to God. That there are cases in which Christians, during a revival, have had so much to do with the hearts of others, that they have neglected their own; and that there is danger, from the very constitution of the human mind, that an enlivened and elevated state of Christian affections will be followed by spiritual languor and listlessness, I admit; but I maintain that these are not necessary evils; and that the Christian, by suitable watchfulness and effort, may avoid them.

It is not in human nature always to be in a state of strong excitement; but it is possible for any Christian to maintain habitually that spirit of deep and earnest piety, which a revival is so well fitted to awaken and cherish. The last objection against revivals which I shall notice is, that they cherish the spirit of sectarism, and furnish opportunities and inducements to different denominations to make proselytes.

I own, Brethren, with grief and shame for our common imperfections, that the evil contemplated in this objection frequently does occur; and though, for a time, different sects may seem to co-operate with each other for the advancement of the common cause, yet they are exceedingly apt, sooner or later, to direct their efforts mainly to the promotion of their own particular cause; and sometimes it must be confessed the greater has seemed to be almost forgotten in the less. Wherever this state of things exists, it is certainly fraught with evil; and the only remedy to be found for it is an increased degree of intelligence, piety, and charity, in the church.

But here again, let me remind you that, let this evil be as great as it may, the most that you can say of its connexion with revivals is, that they are the innocent occasion of it—not the faulty cause. Suppose an individual, or any number of individuals, were to take occasion from the fact that we are assembled here for religious worship, to come in, in violation of the laws of the land, and by boisterous and menacing conduct, to disturb our public service; and suppose they should find themselves forthwith within the walls of a jail ;—the fact of our being here engaged in the worship of God might be the occasion of the evil which they had brought upon themselves; but surely no man in the possession of his reason would dream that it was the responsible cause.

In like manner, a revival may furnish an opportunity, and suggest an inducement, to different religious sects to bring as many into their particular communion as they can; and they may sometimes do this in the exercise of an unhallowed party spirit; but the evil is to be charged, not upon the revival, but upon the imperfections of Christians and ministers, which have taken occasion from this state of things, thus to come into exercise. The revival is from above: But the fallacy of this objection may best be seen by a comparison of the evil complained of, with the good that is achieved.

You and I are Presbyterians: As Presbyterians we have a right, and it is our duty to take special heed to the interests of our own church; but much as we may venerate her order or her institutions, who among us is there that does not regard Christian as a much more hallowed name? In other words, where is the man who would not consider it comparatively a light matter whether an individual should join our particular communion or some other, provided he gave evidence of being a real disciple of Christ?

Now apply this remark to revivals. The evil complained of is, that different sects manifest an undue zeal to gather as many of the hopeful subjects of revivals as they can into their respective communions. Suppose it be so—and what is the result? Why that they are training up—not as we should say, perhaps, under the best form of church government, or possibly the most unexceptionable views of Christian doctrine—but still in the bosom of the church of God, under the dispensation of his word, and in the enjoyment of his ordinances, and in communion with his people—are training up to become members of that communion in which every other epithet will be merged in that of sons and daughters of the Lord Almighty.

Place then, on the one side, the fact that these individuals are to remain in their sins, supposing there is no revival of religion, and on the other, the fact that they are to be proselyted, if you please, to some other Christian sect, provided there is one; and then tell me whether the objection which I am considering does not dwindle to nothing. I would not deem it uncharitable to say that the man who could maintain this objection in this view, that is, the man who could feel more complacency in seeing his fellow men remain in his own denomination dead in trespasses and sins, than in seeing them join other denominations giving evidence of being the followers of the Lord Jesus, whatever other sect he may belong to, does not belong to the sect of true disciples.

Whatever may be his shibboleth, rely on it, he has not learned to talk in the dialect of heaven. I have presented this subject before you, my friends, at considerable length, not because I have considered myself as addressing a congregation hostile to revivals—for I bear you testimony that it is not so—but because most of the objections which have been noticed are more or less current in the community, and I have wished to guard you against the influence of these objections on the one hand, and to assist you to be always ready to give an answer to any one that asketh a reason of your views of this subject on the other.

And may your labors be characterized by such Christian prudence, and tenderness, and fidelity, that while you shall see a rich blessing resting upon them, they may have a tendency to silence the voice of opposition, and increase the number of those who shall co-operate with you in sustaining and advancing this glorious cause.

It is impossible to contemplate either the life or writings of the Apostle Paul, without perceiving that the ruling passion of his renewed nature was a desire to glorify God in the salvation of men. A charming illustration of his disinterestedness in the cause of his Master, occurs in the chapter which contains our text. He maintains, both from scripture and from general equity, the right which a minister of the gospel has to be supported by those among whom he labors; and then shows how he had waived that right in favor of the Corinthians, that the purpose of his ministry might be more effectually gained.

Nevertheless we have not used this power, but suffer all things, lest we should hinder the gospel of Christ: The text takes for granted that there may exist certain hindrances to the influence of the gospel. As every genuine revival of religion is effected through the instrumentality of the gospel, it will be no misapplication of the passage to consider it as suggesting some of the OBSTACLES which often exist in the way of a revival; and in this manner I purpose to consider it at the present time.

It is not to be concealed or denied that much has passed at various periods under the name of revivals, which a sound and intelligent piety could not fail to reprobate. There have been scenes in which the decorum due to christian worship has been entirely forgotten; in which the fervor of passion has been mistaken for the fervor of piety; in which the awful name of God has been invoked not only with irreverence but with disgusting familiarity; in which scores and even hundreds have mingled together in a revel of fanaticism.

Now unhappily there are those, and I doubt not good men too, who have formed their opinion of revivals from these most unfavorable specimens. These perhaps, and no others, may have fallen under their observation; and hence they conclude that whatever is reported to them under the name of a revival, partakes of the same general character with what they have witnessed; and hence too they look with suspicion on any rising religious excitement, lest it should run beyond bounds, and terminate in a scene of religious phrenzy.

There are others, I here speak particularly of ministers of the gospel—for their influence is of course most extensively felt on this subject who are led to look with distrust on revivals, merely from constitutional temperament, or from habits of education, or from the peculiar character of their own religious experience; and while they are hearty well wishers to the cause of Christ, they are perhaps too sensitive to the least appearance of animal feeling.

Besides, they not improbably have never witnessed a revival, and as the case may be, have been placed in circumstances least favorable to understanding its nature or appreciating its importance. What is true of one individual in this case, may be true of many; and if the person concerned be a minister of the gospel, or even a very efficient and influential layman, he may contribute in no small degree to form the opinion that prevails on this subject through a congregation, or even a more extensive community. Now you will readily perceive that such a state of things as I have here supposed, must constitute a serious obstacle to the introduction of a revival.

There are cases indeed in which God is pleased to glorify his sovereignty, by marvellously pouring down his Spirit for the awakening and conversion of sinners, where there is no special effort on the part of his people to obtain such a blessing; but it is the common order of his providence to lead them earnestly to desire, and diligently to seek, the blessing, before he bestows it. But if, instead of seeking these special effusions of divine grace, they have an unreasonable dread of the excitement by which such a scene may be attended; if the apprehension that God may be dishonored by irreverence and confusion, should lead them unintentionally to check the genuine aspirations of pious zeal, or even the workings of religious anxiety, there is certainly little reason to expect in such circumstances a revival of religion.

I doubt not that a case precisely such as I have supposed has sometimes existed; and that an honest, but inexcusably ignorant conscience on the part of a minister or of a church, has prevailed to prevent a gracious visit from the Spirit of God. Another obstacle to a revival of religion is found in a spirit of worldliness among professed christians.

The evil to which I here refer assumes a great variety of forms, according to the ruling passion of each individual, and the circumstances in which he may be placed. There are some of the professed disciples of Christ, who seem to think of little else than the acquisition of wealth; who are not only actively engaged, as they have a right to be, to increase their worldly possessions, but who seem to allow all their affections to be engrossed by the pursuit; who are willing to rise up early, and sit up late, and eat the bread of carefulness, to become rich; and whose wealth, after it is acquired, serves only to gratify a spirit of avarice, or possibly a passion for splendor, but never ministers to the cause of charity.

There is another class of professors whose hearts are set upon worldly promotion; who seem to act as if the ultimate object were to reach some high post of honor; who often yield to a spirit of unhallowed rivalry, and sometimes employ means to accomplish their purposes which christian integrity scarcely knows how to sanction. And there is another class still, not less numerous than either of the preceding, who must be set down in a modified sense at least, as the lovers of pleasure: There are professors of religion among those who take the lead in fashionable life: All these different classes, if their conduct is a fair basis for an opinion, have the world, in some form or other, uppermost.

- Lectures on Revivals of Religion.

- Days Go By;

- re·viv·al·ism;

- Is Your Site an Online Obstacle Course?.

- Christian revival - Wikipedia.

They are quite absorbed with the things which are seen and are temporal. Their conversation is not in heaven. It breathes not the spirit of heaven. It does not relate to the enjoyments of heaven, or the means of reaching those enjoyments. The world take knowledge of them, not that they have been with Jesus, but that like themselves, they love to grovel amidst the things below. That the evil which I have here described existing in a church, must be a formidable obstacle to a revival of religion, none of us probably will doubt.

Let us see for a moment, how it is so. So long as it exists then, it must keep out that general spirituality and active devotedness to the cause of Christ in which a revival, as it respects Christians, especially consists; and of course must prevent all that good influence, which a revival in the church would be fitted to exert upon the world. But suppose there be in the church those who are actually revived, and who have a right estimate of their obligations to labor and pray for the special effusion of divine influences, how manifest is it that this spirit of worldliness must, to a great extent, paralyze their efforts?

How painfully discouraging to them must it be, to behold those who have pledged themselves to co-operate with them in the great cause, turning away to the world, and virtually giving their sanction to courses of conduct directly adapted to thwart their benevolent efforts! And how naturally will careless sinners, when they are pressed by the tender and earnest expostulations of the faithful to flee from the wrath to come, shelter themselves in the reflection that there is another class of professors who estimate this matter differently, and whose whole conduct proclaims that they consider all this talk about religion as unnecessary—not to say fanatical.

But while this spirit of worldliness mocks in a great degree the efforts of the faithful, it exerts a direct and most powerful influence upon those who are glad to find apologies to quiet themselves in sin. I know that it is a miserable fallacy that the inconsistent lives of professed christians constitute any just ground of reproach against the gospel; nevertheless, it is a fact of which no one can be ignorant, that there are multitudes who look at the gospel only as it is reflected in the character of its professors; and especially in their imperfections and backslidings.

These are all strangely looked at, as if religion were responsible for them; and whether it be a particular act of gross transgression, or a general course of devotedness to the world, it will be almost sure to be turned to account in support of the comfortable doctrine that religion does not make men the better, and therefore it is safe to let it alone altogether: None surely will question that whatever exerts such an influence as this on the careless and ungodly, must constitute a powerful barrier to a revival of religion.

What then do professing Christians virtually say to the Holy Spirit, when they lose sight of their obligations, and open their hearts and their arms to the objects and interests of the world? Do they thereby invite him to come, and be with them, and dwell with them, and to diffuse his convincing and converting influences all around? Or do they not rather proclaim their indifference, to say the least, to his gracious operations; and sometimes even virtually beseech him to depart out of their coasts? But it is the manner of our God to bestow his Spirit in unison with the desires and in answer to the prayers of his people—can we suppose then, that where the spirit of the world has taken the place of the spirit of prayer, and the enjoyments of the world are more thought of than the operations of the Holy Ghost—can we suppose, I say, that He who is jealous of his honor, will send down those gracious influences which are essential to a revival of religion?

Whether, therefore, we consider a worldly spirit among professed Christians, in its relation to themselves, to their fellow professors who are faithful, to the careless world, or to the Spirit of God, we cannot fail to perceive that it must stand greatly in the way of the blessing we are contemplating. The want of a proper sense of personal responsibility among professed Christians, constitutes another obstacle to a revival of religion.

WHAT A REVIVAL OF RELIGION IS

You all know how essential it is to the success of any worldly enterprize, that those who engage in it should feel personally responsible in respect to its results. Bring together a body of men for the accomplishment of any object, no matter how important, and there is always danger that personal obligation will be lost sight of; that each individual will find it far easier to do nothing, or even to do wrong, than if, instead of dividing the responsibility with many, he was obliged literally to bear his own burden.

And just in proportion as this spirit pervades any public body, it may reasonably be expected either that they will accomplish nothing, or nothing to any good purpose. Now let this same spirit pervade a church, or any community of professed Christians, and you can look for nothing better than a similar result. Let each professor regard his own personal responsibility as merged in the general responsibility of the church, and the certain consequence will be that the church as a body will accomplish nothing.

Each member may be ready to deplore the prevalence of irreligion and spiritual lethargy, and to acknowledge that something ought to be done in the way of reform; but if, at the same time, he cast his eye around upon his fellow professors, and reflect that there are many to share with him the responsibility of inaction, and that, as his individual exertions could effect but little, so his individual neglect would incur but a small proportion of the whole blame—if he reason in this way, I say, to what purpose will be all his acknowledgments and all his lamentations?

There must also be diligent, and persevering, and self-denied effort; but where are the persons who are ready for this, provided each one feels that he has no personal responsibility? Who will warn the wicked of his wicked way, and exhort him to turn and live? Who will stretch out his hand to reclaim the wandering Christian, or open his lips to stir up the sluggish one? Who, in short, will do anything that God requires to be done in order to the revival of his work, if the responsibility of the whole church is not regarded as the responsibility of the several individuals who compose it?

Wherever you see a church in which this mistaken view of obligation generally prevails, you may expect to see that church asleep; and sinners around asleep; and you need not look for the breaking up of that slumber, until Christians have come to be weighed down under a sense of personal obligation. Wherever you find professors of religion who have little or no sense of their own obligations apart from the general responsibility of the church, there you may look with confidence for that wretched inconsistency, that careless and unedifying deportment that is fitted to arm sinners with a plea against the claims of religion, which they are always sure to use to the best advantage.

And on the other hand, wherever you see professing Christians realizing that arduous duties devolve upon them as individuals, and that the indifference of others can be no apology for their own, there you will see a spirit of self-denial, and humility, and active devotedness to the service of Christ, which will be a most impressive exemplification of the excellence of the gospel, and which will be fitted at once to awaken sinners to a conviction of its importance, and to attract them to a compliance with its conditions.

In short, you will see precisely that kind of agency on the part of Christians which is most likely to lead to a revival, whether you consider it as hearing directly on the minds of sinners, or as securing the influence of the Spirit of God. The toleration of gross offences in the church, is another serious hindrance to a revival of religion. We cannot suppose that the Saviour expected that the visible church on earth would ever be entirely pure; or that there would not be in it those who were destitute of every scriptural qualification for its communion; or even those whose lives would be a constant contradiction of their profession, and a standing reproach upon his cause.

Hence Christians are exhorted to stir up one another by putting each other in remembrance; to reprove and admonish each other with fidelity as occasion may require; and in case of scandalous offences persisted in or not repented of, the church as a body is bound to cut off the offender from her communion. In performing this last and highest act of discipline, as well as in all the steps by which she is led to it, she acts, not according to any arbitrary rules of her own, but under the authority, and agreeably to the directions of her Head.

Now it is impossible to look at the state of many churches, without perceiving that there is a sad disregard to the directions of the Lord Jesus Christ, in respect to offending members. It sometimes happens that professors of religion are detected in grossly fraudulent transactions; that they grind the face of the widow and orphan; that they take upon their lips the language of cursing, and even profanely use the awful name of God; not to speak of what has been more common in other days—their reeling under the influence of the intoxicating draught—I say it sometimes happens that Christian professors exemplify some or other of these vices, and still retain a regular standing in the church, and perhaps never even hear the voice of reproof; especially if the individuals concerned happen to possess great worldly influence, and the church, as it respects temporal interests, is in some measure dependent upon them.

But rely on it, Brethren, this is an evil which is fitted to reach vitally the spiritual interests of the church; and wherever it exists, it will in all probability constitute an effectual obstacle to a revival of religion. For its influence will be felt, in the first place, by the church itself.

The fact that it can tolerate gross offences in its members, proves that its character for spirituality is already low; but the act of tolerating them must necessarily serve to depress it still more. It results from our very constitution and from the laws of habit, that to be conversant with open vice, especially where there is any temptation to apologize for it, is fitted to lessen our estimate of its odiousness, and to impair our sense of moral and Christian obligation.

If a church tolerates in its members scandalous sins, it must know as a body that it is in the wrong; nevertheless each individual will reconcile it to his own conscience as well as he can; and one way will be by endeavoring to find out extenuating circumstances, and possibly to lower a little the standard of Christian character.

Besides, the neglect of one duty always renders the neglect of others more easy; not merely from the fact that there is an intimate connection between many of the duties which devolve upon Christians, but because every known deviation from the path of rectitude has a tendency to lower the tone of religious sensibility, and to give strength to the general propensity to evil. Let the members of a church do wrong in the particular of which I am speaking, and it will make it more easy for them to do wrong in other particulars. A disregard to their covenant obligations in this respect, will render them less sensible of the solemnity and weight of their obligations generally: But the evil to which I refer is not less to be deprecated in its direct influence upon the world, than upon the church.

Christian revival

For here is presented a professing Christian, not only practising vices, which, it may be, would scarcely be tolerated in those who were professedly mere worldly men, but practising these vices, for aught that appears, under the sanction of the church. Wherever this flagrant inconsistency is exhibited, the scoffer looks on and laughs us to scorn. The decent man of the world concludes, that if the church can tolerate such gross evils, whatever other light she may diffuse around her, it cannot be the light of evangelical purity.

Need I say that there is every thing here to lead sinners to sleep on in carnal security to their dying day? But observe still farther, that this neglect to purify the church of scandalous offences, is an act of gross disobedience to her Head; to him who has purchased for her all good gifts; and whose prerogative it is to dispense the influences of the Spirit.

Suppose ye then that he will sanction a virtual contempt of his authority by pouring down the blessings of his grace?

revivalism

Suppose ye that, if a church set at naught the rules which he has prescribed, and not only suffer sin, but the grossest sin, in her members, to go unreproved, he will crown all this dishonor done to his word, all this inconsistency and flagrant covenant-breaking, with a revival of religion? No, Brethren, this is not the manner of Him who rules King in Zion. He never loses sight of the infallible directory, which he has given to his church; and if any portion of his church lose sight of it, it is at the peril of his displeasure.

Disobedience to his commandments may be expected always to incur his frown; and that frown will be manifested at least by withholding the influences of his grace. Another powerful hindrance to a revival of religion, is found in the absence of a spirit of brotherly love among the professed followers of Christ. Christianity never shines forth with more attractive loveliness, or addresses itself to the heart with more subduing energy, than when it is seen binding the disciples of Jesus together in the endearing bonds of a sanctified friendship.

The influence of such an example upon the careless, must be to lower their estimate of the importance of religion, and furnish them an excuse for neglecting to seek an interest in it. Oh how often has it been said by infidels and the enemies of godliness, to the reproach of the cause of Christ, that when Christians would leave off contending with each other, it would be time enough for them to think of embracing their religion! But the want of brotherly love operates to prevent a revival of religion, still farther, as it prevents that union of Christian energy, in connection with which God ordinarily dispenses his gracious influences.

It prevents a union of counsel. As the Saviour has committed his cause in a sense into the hands of his people, so he has left much as respects the advancement of it, to their discretion. And they are bound to consult together with reference to this end; and to bring their concentrated wisdom to its promotion. The same spirit will prevent a union in prayer. This is the grand means by which men prevail with God; and the prospect of their success is always much in proportion to the strength of their mutual Christian affection;—for this is a Christian grace; and if it is in lively exercise, other Christian graces which are more immediately brought into exercise in prayer, such as faith repentance and humility, will not be asleep: But on the other hand, if there be not this feeling of brotherly kindness among professed Christians, even if they come together to pray for the out-pouring of the Spirit, their prayers will at best be feeble and inefficient, and their thoughts will not improbably be wandering, and unchristian feelings towards each other kindling, at the very time they are professedly interceding for the salvation of sinners.

And the same spirit is equally inconsistent with a union of Christian effort; for if they cannot take counsel together, if they cannot pray together, they surely cannot act together. Most unquestionably not on you, but on those who accused you. There is nothing in the obligation of good will which Christians owe to each other, to set aside the paramount obligation which they owe to their Master, to take his word as the rule of their practice. Whatever you conscientiously believe to be unscriptural, you are bound to decline at any hazard; and if you do it kindly, no matter how firmly and the charge of being wanting in brotherly love is preferred against you, you have a right to repel it as an unchristian accusation.

If, in such a case, evil result from the want of concentrated action, and the measures adopted are really unscriptural, the responsibility rests upon those who, by the adoption of such measures, however honestly they may do it compel you to stand aloof from them. You may indeed, in other ways, give evidence of not possessing the right spirit towards them; and it becomes you to take heed that you do not give such evidence; but the mere fact of refusing your co-operation certainly does not constitute it.

And it would be well if they should inquire whether they are not at as great a distance from you as you are from them; and whether their departure from you does not indicate as great a want of brotherly love as is indicated by the fact of your refusing to follow them? But it may be asked whether a spirit of brotherly love may not exist between Christians whose views on points not fundamental may differ?

I answer, yes undoubtedly; it may and ought to exist among all who trust in a common Saviour. We may exercise this spirit even towards those whom we regard as holding errors, either of faith or practice, provided we can discover in them the faintest outline of the image of Christ.

They may adopt opinions in which we cannot harmonize, and measures in which we cannot co-operate, and the consequence of this may be a loss of good influence to the cause of Christ, and perhaps positive evil resulting from disunion in effort; nevertheless we may still recognize them as Christians, and love them as Christians, and cordially co-operate with them, wherever our views and theirs may be in harmony.

The right spirit among Christians would lead them to make as little of their points of difference, and as much of their common ground, as they can; and where they must separate, to do it with kindness and good will, not with bitterness and railing. I must not dismiss this article without saying that the Spirit of God who is active in awakening and renewing sinners, is the Spirit of peace; he dwells not in scenes of contention; and we cannot reasonably expect his presence or agency, where Christians, instead of being fellow workers together unto the kingdom of God, are alienated from each other, and sell themselves to the service of a party.

In accordance with this sentiment, it has often been found in actual experience that the Spirit of God has fled before the spirit of strife; and a revival of religion which promised a glorious result, has been suddenly arrested by some unimportant circumstance, which the imperfections of good men have magnified, till they have made it an occasion of controversy. The last hindrance to a revival which.

I shall notice, is an erroneous or defective exhibition of Christian truth. As it is through the instrumentality of the truth that God performs his work upon the hearts of men, it is fair to conclude that just in proportion as any part of it is kept back, or is dispensed in a different manner from that which he has prescribed, it will fail of its legitimate effect. In the exercise of their own judgment on this subject, they may come to the conclusion that particular parts of divine truth are of little importance; and that even some of the peculiar doctrines of the gospel may well enough be lightly passed over; but this is an insult to the author of the Bible which they have good reason to expect he will punish by sending them a barren ministry.

There is a way of preaching certain doctrines out of their proper connection, which is exceedingly unfriendly to revivals of religion. It is natural for them to find excuses for remaining in a state of sinful security as long as they can; and so long as they are furnished with such excuses as these, and by the ministers of the gospel, there is not the least ground for expecting that their consciences will be disturbed.

Let the naked sword of the Spirit be brought home to the consciences of men, and the effect of it must and will be felt, and the anxious inquiry will be heard, and sinners, in all probability, will be renewed. But let the wire-drawn theories of metaphysicians be substituted in place of the simple truth; or even let the genuine doctrines of the gospel be customarily exhibited in connection with the refined speculations of human philosophy; and though I dare not say that God in his sovereignty may not bless the truth which is actually preached, yet I may say with confidence that but little effect can be reasonably expected from such a dispensation of the word.

And the reasons are obvious; for God has promised to bless nothing but his own truth; and the refinements of philosophy are to the mass of hearers quite unintelligible. I may add that a want of directness in the manner of preaching the gospel, may prevent it from taking effect on the consciences and hearts of men. It is only when men are made to feel that the gospel comes home to their individual case, that they are themselves the sinners whom it describes, and that they need the blessings which it offers,—it is only then, I say, that they hear it to any important purpose.

Suppose that its doctrines, instead of being exhibited in their practical bearings, and enforced by strong appeals to the conscience, are discussed merely as abstract propositions, and with no direct application, the consequence will be that, though the great truths of the Bible may be presented before the mind, yet they will rarely, if ever, sink into the heart.