One particular battle in between students and the townspeople in a tavern left five persons dead; King Philip II was called in to define the rights and legal status of students formally. Thereafter, the students and teachers were gradually organized into a corporation that was officially recognized in as a university by Pope Innocent III , who had studied there.

In the 13th century, there were between two and three thousand students living in the Left Bank, which became known as the Latin Quarter , because Latin was the language of instruction at the university. The number grew to about four thousand in the 14th century.

In , the chaplain of Louis IX, Robert de Sorbon , opened the most famous college of the university, which was later named after him: The University of Paris was originally organized into four faculties: The arts and letters students were the most numerous; their courses included grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

Their course of study led first to a bachelor's degree , then a master's degree , which allowed them to teach. Students began at the age of fourteen and studied at the faculty of arts until they were twenty. The completion of a doctorate in theology required a minimum of another ten years of study.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the University of Paris grew in size and experienced almost continual conflicts between students and the townspeople. It was also divided by all of the theological and political conflicts of the period: By the end of the Middle Ages, the University had become a very conservative force against any change in society. Dissection of corpses was forbidden in the medical school long after it became common practice at other universities, and unorthodox ideas were regularly condemned by the faculty; individuals viewed as heretics were punished.

In February , a tribunal of faculty members led by Pierre Cauchon was called upon by the English and Burgundians to judge whether Joan of Arc was guilty of heresy. After three months of study, they found her guilty on all charges, and demanded her rapid execution. The population of medieval Paris was strictly divided into social classes, whose members wore distinctive clothing, followed strict rules of behavior, and had very distinct roles to play in society. At the top of the social structure was the hereditary nobility.

Just below the nobility were the clerics, who made up about ten percent of the city population with the inclusion of students. They maintained their own separate and strict hierarchy. Unlike the nobility, it was possible for those with talent and modest means to enter and advance in the clergy; Maurice de Sully came from a family of modest means to become the Bishop of Paris and builder of Notre-Dame cathedral.

The wealthy merchants and bankers were a small part of the population, but their power and influence grew throughout the Middle Ages. In the 13th century, the bourgeois of Paris, those who paid taxes, amounted to about fifteen percent of the population. According to tax records at the end of the 13th century, the wealthiest one percent of Parisians paid eighty percent of the taxes. According to tax records, the wealthy bourgeois of Paris between and numbered just families or about two thousand persons.

The great majority of Parisians, about 70 percent, paid no taxes and led a very precarious existence. Fortunately for the poor, the theology of the Middle Ages required the wealthy to give money to the poor and warned them that it would be difficult for them to enter Heaven if they were not charitable. Noble families and the wealthy funded hospitals, orphanages, hospices, and other charitable institutions in the city.

Medieval Warfare

Early in the Middle Ages, beggars were generally respected and had an accepted social role. Commerce was a major source of the wealth and influence of Paris in the Middle Ages. Even before the Roman conquest of Gaul, the first inhabitants of the city, the Parisii , had traded with cities as far away as Spain and Eastern Europe and had minted their own coins for this purpose.

In the Gallo-Roman town of Lutetia, the boatmen dedicated a column to the god Mercury that was found during excavations under the choir of Notre Dame. In , during the reign of Louis VI, the king accorded to the league of boatmen of Paris a fee of sixty centimes for each boatload of wine that arrived in the city during the harvest.

In , Louis VII extended the privileges of the river merchants even further; only the boatmen of Paris were allowed to conduct commerce on the river between the bridge of Mantes and the two bridges of Paris; the cargoes of other boats would be confiscated. This was the beginning of the close association between the merchants and the king. The arrangement with the river merchants coincided with a great expansion of commerce and increase in the population on the Right Bank of the city.

The large monasteries also played an important role in the growth of commerce in the Middle Ages by holding large fairs that attracted merchants from as far away as Saxony and Italy. The Abbey of Saint Denis had been holding a large annual fair since the seventh century; the fair of Saint-Mathias dated to the 8th century; The Lenit Fair appeared in the 10th century, and the Fair of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres began in the 12th century.

The King also gave the corporation the power to supervise the accuracy of the scales used in the markets, and to settle minor commercial disputes. By the 15th century separate ports were established along the river for the delivery of wine, grain, plaster, paving stones, hay, fish, and charcoal. Wood for cooking fires and heating was unloaded at one port, while wood for construction arrived at another. The merchants engaged in each kind of commerce gathered around that port; in , of the twenty-one wine merchants registered in Paris, eleven were located between the Pont Notre-Dame and the hotel Saint-Paul, the neighborhood where their port was located.

In the early Middle Ages, the principal market of Paris was located on the parvis square in front of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. Other markets took place in the vicinity of the two bridges, the Grand Pont and the Petit Pont , while a smaller market called Palu or Palud, took place in the eastern neighborhood of the city. This market was the site of the Grande Boucherie , the main meat market of the city. It continued to be the main produce market in Paris until the late 20th century, when it was transferred to Rungis in the Paris suburbs.

There were other more specialized markets within the city: Later, during the reign of Charles V, the meat market was transferred to the neighborhood of the Butte Saint-Roche. The second important business community in Paris were that of the artisans and craftsmen, who produced and sold goods of all kinds. They were organized into guilds , or corporations, that had strict rules and regulations to protect their members against competition and unemployment. The oldest four corporations were the drapiers , who made cloth; the merciers , who made and sold clothing, the epiciers , who sold food and spices, and the pelletiers , who made fur garments, but there were many more specialized professions, ranging from shoemakers and jewelers to those who made armor and swords.

The guilds strictly limited the number of apprentices in each trade and the number of years of apprenticeship. Certain guilds tended to gather on the same streets, though this was not a strict rule. The manufacture of cloth was important until the 14th century, but it lost its leading role to competition from other cities and was replaced by crafts which made more finished clothing items: Money changers were active in Paris since at least ; they knew the exact values of all the different silver and gold coins in circulation in Europe. They had their establishments primarily on the Grand Pont, which became known as the Pont aux Changeurs and then simply the Pont au Change.

Tax Records show that in the money changers were among the wealthiest persons in the city; of the twenty persons with the highest incomes, ten were money changers. Between and , four money changers occupied the position of Provost of the Merchants. But by the end of the 15th century, the system of wealth had changed; the wealthiest Parisians were those who had bought land or positions in the royal administration and were close to the king.

Some money changers branched into a new trade, that of lending money for interest. Since this was officially forbidden by the Catholic Church, most in the profession were either Jews or Lombards from Italy. The Lombards, connected to a well-organizer banking system in Italy, specialized in loans to the wealthy and the nobility. Originally, the position was purchased for a large sum of money, but after scandals during the reign of Louis IX caused by provosts who used the position to become rich, the position was given to proven administrators. He combined the positions of financial manager, chief of police, chief judge and chief administrator of the city, though the financial management position was soon taken away and given to a separate Receveur de Paris.

He also had two "examiners" to carry out investigations. In , the provost was given an additional staff of sixty clerks to act as notaries to register documents and decrees. This position recognized the growing power and wealth of the merchants of Paris. He also created the first municipal council of Paris with twenty-four members.

The Parlement de Paris was created in It was a national, not a local, institution and functioned as a court rather than a legislature by rendering justice in the name of the king. It was usually summoned only in difficult periods when the king wanted to gather broader support for his actions. With the growth in population came growing social tensions. The first riots against the Provost of the Merchants took place in December , when the merchants were accused of raising rents. The houses of many merchants were burned, and twenty-eight rioters were hanged. After initial concessions by the Crown, the city was retaken by royalist forces in and Marcel and his followers were killed.

Thereafter, the powers of the local government were considerably reduced, and the city was kept much more tightly under royal control. The streets of Paris were particularly dangerous at night because of the absence of any lights. As early as AD, Chlothar II , King of the Franks, required that the city have a guet , or force of watchmen, to patrol the streets. This night watch was insufficient to maintain security in such a large city, so a second force of guardians was formed whose members were permanently stationed at key points around Paris.

The two guets were under the authority of the Provost of Paris and commanded by the Chevalier du guet. The name of the first one, Geofroy de Courferraud, was recorded in He commanded a force of twelve sergeants during the day and an additional twenty sergeants and twelve other sergeants on horseback to patrol the streets at night.

The sergeants on horseback went from post to post to see that they were properly manned. The night watch of the tradesmen continued. This policing system was not very effective. In , it was finally replaced by a larger and more organized force of four hundred soldiers and one hundred cavalry that was reinforced during times of trouble by a militia of one hundred tradesmen from each quarter of the city.

There was no professional force of firemen in the city during the Middle Ages; an edict of required that everyone in a neighborhood join in to fight a fire. The role of firefighters was gradually taken over by monks, who were numerous in the city. The Cordeliers, Dominicans , Franciscans , Jacobins , Augustinians and Carmelites all took an active role in fighting fires.

The first professional fire companies were not formed until the eighteenth century. Paris, like all large medieval cities, had its share of crime and criminals, though it was not quite as portrayed by Victor Hugo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame The "Grand Court of Miracles" described by Victor Hugo, a gathering place for beggars who pretended to be injured or blind, was a real place: Nonetheless, it did not have the name recorded by Hugo or a reputation as a place the police feared to enter until the 17th century.

The most common serious crime was murder, which accounted for 55 to 80 percent of the major crimes described in court archives. It was largely the result of the strict code of honor in effect in the Middle Ages; an insult, such as throwing a person's hat in the mud, required a response, which often led to a death.

A man whose wife committed adultery was considered justified if he killed the other man. In many cases, these types of murders resulted in a royal pardon. Thieves cut them loose and ran away. Heresy and sorcery were considered especially serious crimes; witches and heretics were usually burned, and the king sometimes attended the executions to display his role as defender of the Christian faith. Others were decapitated or hanged. Beginning in about , a large gibet was built on a hill outside of Paris, near the modern Parc des Buttes Chaumont , where the bodies of executed criminals were displayed.

Prostitution was a separate category of crime. Prostitutes were numerous and mostly came from the countryside or provincial towns; their profession was strictly regulated, but tolerated. Prostitutes could be found in taverns, cemeteries, and even in cloisters. Prostitutes were forbidden to wear furs, silks, or jewelry, but regulation was impossible, and their numbers continued to increase. The Church had its own system of justice for the ten percent of the Paris population who were clerics, including all the students of the University of Paris.

Most clerical offenses were minor, ranging from marriage to deviations from official theology. The Bishop had his own pillory on the square in front of Notre Dame, where clerics who had committed crimes could be put on display. For more serious crimes, the Bishop had a prison in a tower adjoining his residence next to the Cathedral, as well as several other prisons for conducting investigations in which torture was permitted. The church courts could condemn clerics to corporal punishment or banishment. In the most extreme cases, such as sorcery or heresy , the Bishop could pass the case to the Provost and civil justice system, which could burn or hang those convicted.

This was the process used in the case of the leaders of the Knights Templar. He and his two examiners were responsible for judging crimes ranging from theft to murder and sorcery. Royal prisons existed in the city; about a third of their prisoners were debtors who could not pay their debts. Wealthier prisoners paid for the own meals and bed, and their conditions were reasonably comfortable. Prisoners were often released and banished, which saved the royal treasury money.

Higher crimes, particularly political crimes, were judged by the Parlement de Paris, which was composed of nobles. The death sentence was very rarely given in Paris courts, only four times between and Most prisoners were punished with banishment from the city. The time of day in medieval Paris was announced by the church bells, which rang eight times during the day and night for the different calls to prayer at the monasteries and churches: Prime , for instance, was at six in the morning, Sext at midday, and Vespers at six in the evening, though later in summer and earlier in the winter.

The churches also rang their bell for a daily curfew at seven in the evening in winter and eight in summer. The working day was usually measured by the same bells, ending either at vespers or at the curfew. There was little precision in timekeeping, and the bells rarely rang at exactly the same time. The first mechanical clock in Paris appeared in , and in , a clock was recorded at the Sainte-Chapelle. It was not until , under Charles V, who was particularly concerned by precise time, that a mechanical clock was installed on a tower of the Palace, which sounded the hours.

This was the first time that the city had an official time of day.

- Introduction to the middle ages | Art history (article) | Khan Academy?

- Illuminated manuscript.

- Computergrafik für Ingenieure: Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung (German Edition).

- Introduction to the middle ages;

- Design First: Design-based Planning for Communities.

By , the churches of Saint-Paul and Saint-Eustache also had clocks, and time throughout the city began to be standardized. During the Middle Ages, the staple food of most Parisians was bread. Mills near the Grand Pont turned it into flour. During the reign of Philip II, a new grain market was opened at Les Halles , which became the main market. When the harvest was poor, the royal government took measures to assure the supply of grain to the city. When Henry II died shortly afterwards his last words to Richard were allegedly "God grant that I may not die until I have my revenge on you".

On the day of Richard's English coronation there was a mass slaughter of the Jews, described by Richard of Devizes as a "holocaust". Richard captured the city of Messina on 4 October and using it to force Tancred into a peace agreement. Opinions of Richard amongst his contemporaries were mixed. He had rejected and humiliated the king of France's sister; insulted and refused spoils of the third crusade to nobles like Leopold V, Duke of Austria , and was rumoured to have arranged the assassination of Conrad of Montferrat.

His cruelty was demonstrated by his massacre of 2, prisoners in Acre. He achieved victories in the Third Crusade but failed to capture Jerusalem, retreating from the Holy Land with a small band of followers. Richard was captured by Leopold on his return journey in Custody was passed to Henry the Lion and a tax of 25 percent of movables and income was required in England to pay the ransom of , marks, with a promise of 50, more, before Richard was released in On his return to England, Richard forgave John and re-established his control.

Leaving England in never to return, Richard battled Phillip for the next five years for the return of the holdings seized during his incarceration. Richard's failure in his duty to provide an heir caused a succession crisis. Yet again Philip II of France took the opportunity to destabilise the Plantagenet territories on the European mainland, supporting his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown.

When Arthur's forces threatened his mother, John won a significant victory, capturing the entire rebel leadership at the Battle of Mirebeau. John's behaviour drove numerous French barons to side with Phillip. The resulting rebellions by the Norman and Angevin barons broke John's control of the continental possessions, leading to the de facto end of the Angevin Empire, even though Henry III would maintain the claim until After re-establishing his authority in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou.

However, his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines in one of the most decisive and symbolic battles in French history. Philip's decisive victory was crucial in ordering politics in both England and France. The battle was instrumental in forming the absolute monarchy in France. John's defeats in France weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in the treaty called Magna Carta , which limited royal power and established common law. This would form the basis of every constitutional battle through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

This is considered by some historians to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty with John's death and William Marshall's appointment as the protector of the nine-year-old Henry III. Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the Anglo-Saxon elite had been replaced by a new class of Norman nobility. The method of government after the conquest can be described as a feudal system , in that the new nobles held their lands on behalf of the king; in return for promising to provide military support and taking an oath of allegiance, called homage , they were granted lands termed a fief or an honour.

At the centre of power, the kings employed a succession of clergy as chancellors , responsible for running the royal chancery, while the familia regis , the military household, emerged to act as a bodyguard and military staff. King John extended the royal role in delivering justice, and the extent of appropriate royal intervention was one of the issues addressed in the Magna Carta of Many tensions existed within the system of government.

Medieval England was a patriarchal society and the lives of women were heavily influenced by contemporary beliefs about gender and authority. The rights and roles of women became more sharply defined, in part as a result of the development of the feudal system and the expansion of the English legal system; some women benefited from this, while others lost out. Married or widowed noblewomen remained significant cultural and religious patrons and played an important part in political and military events, even if chroniclers were uncertain if this was appropriate behaviour.

The Normans and French who arrived after the conquest saw themselves as different from the English. They had close family and economic links to the Duchy of Normandy, spoke Norman French and had their own distinctive culture. The English perceived themselves as civilised, economically prosperous and properly Christian, while the Celtic fringe was considered lazy, barbarous and backward. The Norman conquest brought a new set of Norman and French churchmen to power; some adopted and embraced aspects of the former Anglo-Saxon religious system, while others introduced practices from Normandy.

New orders began to be introduced into England. As ties to Normandy waned, the French Cluniac order became fashionable and their houses were introduced in England. William the Conqueror acquired the support of the Church for the invasion of England by promising ecclesiastical reform. Kings and archbishops clashed over rights of appointment and religious policy, and successive archbishops including Anselm , Theobald of Bec , Thomas Becket and Stephen Langton were variously forced into exile, arrested by royal knights or even killed.

Pilgrimages were a popular religious practice throughout the Middle Ages in England, with the tradition dating back to the Roman period. The idea of undertaking a pilgrimage to Jerusalem was not new in England, as the idea of religiously justified warfare went back to Anglo-Saxon times. England had a diverse geography in the medieval period, from the Fenlands of East Anglia or the heavily wooded Weald , through to the upland moors of Yorkshire.

Of the 10, miles of roads that had been built by the Romans, many remained in use and four were of particular strategic importance—the Icknield Way , the Fosse Way , Ermine Street and Watling Street —which criss-crossed the entire country. For much of the Middle Ages, England's climate differed from that in the twenty-first century. The English economy was fundamentally agricultural , depending on growing crops such as wheat , barley and oats on an open field system , and husbanding sheep , cattle and pigs.

Although the Norman invasion caused some damage as soldiers looted the countryside and land was confiscated for castle building, the English economy was not greatly affected. Anglo-Norman warfare was characterised by attritional military campaigns, in which commanders tried to raid enemy lands and seize castles in order to allow them to take control of their adversaries' territory, ultimately winning slow but strategic victories. Pitched battles were occasionally fought between armies but these were considered risky engagements and usually avoided by prudent commanders.

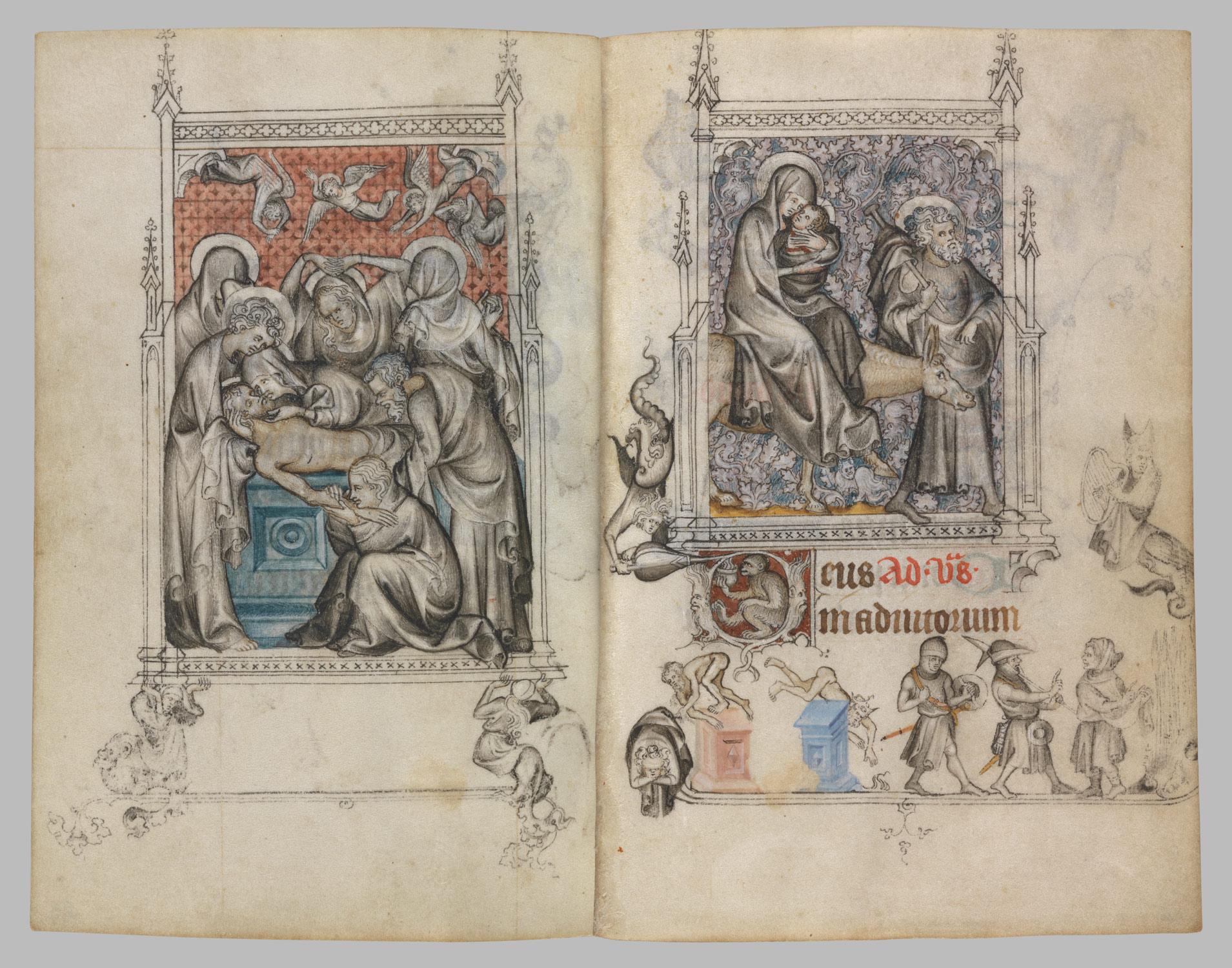

Crossbowmen become more numerous in the twelfth century, alongside the older shortbow. Naval forces played an important role during the Middle Ages, enabling the transportation of troops and supplies, raids into hostile territory and attacks on enemy fleets. Although a small number of castles had been built in England during the s, after the conquest the Normans began to build timber motte and bailey and ringwork castles in large numbers to control their newly occupied territories. The Norman conquest introduced northern French artistic styles, particular in illuminated manuscripts and murals, and reduced the demand for carvings.

Very few examples of glass survive from the Norman period, but there are a few examples that survive from minor monasteries and parish churches. The largest collections of twelfth-century stained glass at the Cathedrals of York and Canterbury. Poetry and stories written in French were popular after the Norman conquest, and by the twelfth century some works on English history began to be produced in French verse. The Normans brought with them architectural styles from their own duchy, where austere stone churches were preferred. Under the early Norman kings this style was adapted to produce large, plain cathedrals with ribbed vaulting.

The elite preferred houses with large, ground-floor halls but the less wealthy constructed simpler houses with the halls on the first floor; master and servants frequently lived in the same spaces. The period has been used in a wide range of popular culture. William Shakespeare 's plays on the lives of the medieval kings have proved to have had long lasting appeal, heavily influencing both popular interpretations and histories of figures such as King John.

Prince of Thieves and Kingdom of Heaven From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Part of a series on the. Social history of England History of education in England History of the economy of England History of the politics of England English overseas possessions History of the English language. By city or town. Prehistoric Britain until c. For other uses, see Norman England disambiguation. William I of England. William II of England. Henry I of England. The Anarchy and Stephen, King of England. Angevin kings of England. Henry II of England. Richard I of England. John, King of England.

Social history of the High Middle Ages. Women in the Middle Ages and Anglo-Saxon women. Religion in Medieval England. Church and state in medieval Europe. Middle Ages in popular culture. The Journal of British Studies. The Feudal Kingdom of England, — William Rufus Second ed. England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings, — The chief engineer hurled a pot of molten pitch at it, hitting it in exactly the right spot and it burst into flames.

A Cat depicted at Carcassonne. Incendiary devices were standard weapons of war. Wooden defences always needed protection from burning. Wet animal hides were highly effective against burning arrows so military engineers dedicated themselves to finding ways of ensuring that fires burned as long and as strongly as necessary to catch. All sorts of chemicals could be used for this purpose - petroleum, sulphur, quicklime and tar barrels for example. Liquid fire is represented on Assyrian bas-reliefs.

At the siege of Plataea in BC the Spartans attempted to burn the town by piling up against the walls wood saturated with pitch and sulphur and setting it on fire, and at the siege of Delium in BC a cauldron containing pitch, sulphur and burning charcoal was placed against the walls. A century later Aeneas Tacticus mentions a mixture of sulphur, pitch, charcoal, incense and tow packed in wooden vessels, ignited and thrown onto the decks of enemy ships.

Formulae given by Vegetius around AD add naphtha or petroleum. Some nine centuries later the same substances are found and later recipes include saltpetre and turpentine make their appearance. The ultimate in this form of chemical warfare was called Greek-Fire. Greek fire was a burning-liquid used as a weapon of war by the Byzantines, and also by Arabs, Chinese, and Mongols. Incendiary weapons had been in use for centuries: Greek fire was vastly more potent. Similar to modern napalm, it would adhere to surfaces, ignite upon contact, and could not be extinguished by water alone.

Byzantines used it in naval battles to great effect because it burned on water. It was responsible for numerous Byzantine military victories on land as well as at sea - and also for enemies preferring discretion to valour so that many battles never took place at all.

- Die Bilsenweisheit - Atopia 3 (German Edition)!

- Broken Windows and other poems about existence and near catastrophes.

- Paris in the Middle Ages - Wikipedia.

- Support the Project?

- Mémoires de linachevé: (1954-1993) (VERTICALES) (French Edition).

It was the ultimate deterrent of the time, and helps explain the Byzantine Empire's survival until There was no defence. As the Lord of Joinville noted in the thirteenth century "Every time they hurl the fire at us, we go down on our elbows and knees, and beseech Our Lord to save us from this danger.

On the other hand Greek fire was very hard to control, and it would often accidentally set Byzantine ships ablaze. The formula for Greek fire was a closely guarded secret and it remains a mystery to this day. The term Greek Fire was not attributed to it until the time of the European Crusades. Muslims against whom the weapon was used called the Byzantines Romans. The weapon was first used by the Byzantine navy, and the most common method of deployment was to squirt it through a large bronze tube onto enemy ships. Usually the mixture would be stored in heated, pressurised barrels and projected through the tube by some sort of pump, operators being protected behind large iron shields.

Byzantines used Greek Fire only rarely, apparently out of fear that the secret mixture might fall into enemy hands. The loss of the secret would be a greater loss to Byzantium then the loss of any single battle. In the Byzantines utterly destroyed a Muslim fleet - over 30, men were lost. In Caliph Suleiman attacked Constantinople Byzantium.

Most of the Muslim fleet was once again destroyed by Greek Fire, and the Caliph was forced to flee. There is virtually no documentation of its usage after this time by the Byzantines and it is generally believed that it was during this era that the secret of creating Greek Fire was lost. Formulae used after this date never seems to have had the same devastating effect. Some form of Greek Fire continued to be used for centuries. Byzantines used it against the Venetians during the Fourth Crusade.

A so-called "carcass composition" containing sulphur, tallow, rosin, turpentine, saltpetre and antimony, became known to the Crusaders as Greek fire but is more correctly called wildfire. So far, no-one has been able to recreate Greek Fire. Arabian armies, who eventually created their own version sometime between the mid-seventh century and the early tenth.

Product description

It was relatively weak copy of the original Byzantine substance, though still one of the most devastating weapons of the period. Arabs used the Greek Fire much like Byzantines, using brass tubes mounted aboard ships or on castle walls. They also filled jars with it, to be hurled by hand at their opponents. Arrows and javelins would be used to carry the mixture further and engines of war could be used to throw larger amounts over castle walls. As a defence, water alone was ineffective. On land sand could be used to stop the burning.

Intriguingly it is also known that vinegar and urine were effective - suggesting an alkaline composition that could be neutralised by acid. According to some accounts pure or salt water served to intensify the burning, suggesting that Greek Fire may have been a 'thermite-like' reaction, perhaps involving quicklime. According to some sources, Greek Fire burst into flames on contact with water. Some have suggested phosphorus, Others have suggested a form of naphtha or another low-density liquid hydrocarbon petroleum was already known in the East.

There are numerous candidates including liquid petroleum, naphtha, burning pitch, sulphur, resin, quicklime and bitumen, along with a hypothetical unknown "secret ingredient". The exact composition is unlikely ever to be deduced from the inadequate surviving records. It is not clear from contemporary reports if the operator ignited the mixture with a flame as it emerged from the syringe, or if it ignited spontaneously on contact with water or air. If the latter is the case, it is possible that the active ingredient was calcium phosphide, made by heating lime, bones, and charcoal.

On contact with water, calcium phosphide releases phosphine, which ignites spontaneously. The reaction of quicklime with water also creates enough heat to ignite hydrocarbons, especially if an oxidiser such as saltpetre is present. Ingredients were apparently preheated in a cauldron, and then pumped through a pump or used in hand grenades. If a pyrophoric reaction was involved, perhaps these grenades contained chambers for the fluids, which mixed and ignited when the vessel broke on impact with the target.

More information Professor J. Greek fire was not the only Chemical Weapon. Poisoned arrows could be employed and in the late medieval period gunpowder became common. Medieval warriors also used basic biological weapons, for example catapulting dead and diseased animals into a defended fortress to help spread disease. Ancient armies had used sophisticated psychological weapons.

Paris in the Middle Ages

For example would have mad armour suitable for a man of several times normal size. He would then leave a few samples laying around the scene of his victories against the Persians. After he had gone Persians would find this armour and were were soon spreading stories of Alexander's superhuman giant soldiers. Christendom did not stretch to this level of sophistication, but it did engage in some psychological warfare, spreading rumours for example, sometimes with success effectively turning a military defeat into a political victory.

Other examples of psychological warfare include making loud noises an old Celtic practice and catapulting the severed heads of captured enemies back into the enemy camp. Defenders in castles under siege might prop up dummies beside the walls to make it look like there were more defenders than there really were. They might throw food from the walls to show besiegers that provisions were plentiful Dame Carcas, who saw off the Franks, supposedly gave her name to Carcassonne after feeding the last few scraps of food in the besieged city to the last pig and then tossing over the walls as a present to the Franks.

As intended, they deduced that their siege was useless and raised it the next day. Firearms provided a strong psychological benefit when they were introduced, even though their rate of fire rendered them almost useless - and their users often blew themselves up rather than the enemy - literally hoist by their own petard. The fleet came up with the Pisans between Rhodes and Patara, but as its vessels were pursuing them with too great zeal it could not attack as a single body.

The first to reach the enemy was the Byzantine admiral Landulph, who shot off his fire too hastily, missed his mark and accomplished nothing. But Count Eleemon, who was the next to close, had better fortune; he rammed the stern of a Pisan vessel, so that the bows of his ship got stuck in its steering-oar tackle. Then, shooting forth the fire, he set it ablaze, after which he pushed off and successfully discharged his tube into three other vessels, all of which were soon in flames.

The Pisans then fled in disorder, 'having had no previous knowledge of the device, and wondering that fire, which usually burns upwards, could be directed downwards or to either hand, at the will of the engineer who discharged it'. It happened one night, whilst we were keeping night-watch over the tortoise-towers, that they brought up against us an engine called a perronel which they had not done before and filled the sling of the engine with Greek fire.

History: Middle Ages for Kids

When that good knight, Lord Walter of Cureil, who was with me, saw this, he spoke to us as follows: For, if they set fire to our turrets and shelters, we are lost and burnt; and if, again, we desert our defences which have been entrusted to us, we are disgraced; so none can deliver us from this peril save God alone.

My opinion and advice therefor is: So soon as they flung the first shot, we went down on our elbows and knees, as he had instructed us; and their first shot passed between the two turrets, and lodged just in front of us, where they had been raising the dam. Our firemen were all ready to put out the fire; and the Saracens, not being able to aim straight at them, on account of the two penthouse wings which the King had made, shot straight up into the clouds, so that the fire-darts fell right on top of them. This was the fashion of the Greek fire: It looked like a dragon flying through the air.

Such a bright light did it cast, that one could see all over the camp as though it were day, by reason of the great mass of fire, and the brilliance of the light that it shed. Thrice that night they hurled the Greek fire at us, and four times shot it from the tourniquet cross-bow. A"mine" was a tunnel dug to destabilise and bring down castles and other fortifications. The technique could be used only when the fortification was not built on solid rock.

It was developed as a response to stone built castles that could not be burned like earlier-style wooden forts. A tunnel would be excavated under the outer defences either to provide access into the fortification or more often to collapse the walls. These tunnels were supported by temporary wooden props as the digging progressed, just as in any mine. Once the excavation was complete, the mine was filled with combustible material. When lit it would burn away the props leaving the structure above unsupported and liable to collapse.

To save effort attackers would start the digging as near as possible to the wall or tower to be undermined. This exposed the sappers to enemy fire so it was necessary to provide some sort of defence. Pierre des Vaux de Cernay recounts that at the siege of Carcassonne in , during the Cathar wars Albigensian Crusade ,. Successful sapping usually ended the battle since either the defenders would no longer be able to defend and surrender, or the attackers would simply charge in and engage the defenders in close combat. There were several methods to resist under mining. Often the siting of a castle would be such as to make mining difficult.

The walls of a castle could be constructed either on solid rock or water-logged land making it difficult to dig mines. A very deep ditch or moat could be constructed in front of the walls, or even an artificial. This makes it more difficult to dig a mine and even if a breach is made the ditch or moat makes exploiting the breach difficult.

The defenders could also dig counter mines. From these they could then either dig into the attackers tunnels and sortie into them to either kill the sappers or to set fire to the pit-props to collapse the attackers' tunnel. Alternatively they could undermine the attackers' tunnel to collapse it. If the walls were breached they could either place obstacles in the breach for example a chevaux de frise to hinder an attack, or construct a coupure.

The practice has left us reminders in English. And military engineers are still known as Sappers. Water was essential to any army and the defence of any stronghold. Wherever practical castles were built on the site of natural springs but that was not always possible. Where it was not, much effort went into digging wells or aqueducts sometimes subterranean , or massive cisterns. Many of the castles that fell during the Cathar Wars did so because of a shortage of water, including Termes and Carcassonne. The illustration on the left shows a massive defensive structure built at Carcassonne to ensure a water supply and access to the River Aude.

The usual method for solving logistical problems for smaller armies was foraging or "living off the land" - effectively stealing whatever was needed: The normal "campaign season" corresponded to the seasons of the year when there would be food on the ground and relatively good weather. This season was usually from spring to autumn. Soldiers were rarely full-time and often needed to attend to their own land at home. In many European countries peasants were obliged to perform around 45 days of military service per year without pay, usually during this campaign season when they were not required for agriculture.

By early-spring all the crops would be planted, freeing the male population for warfare until they were needed for harvest time in late-autumn. Plunder in itself was often an objective of military campaigns, to either pay mercenary forces, seize resources, reduce the fighting capacity of enemy forces, or even just as a public insult to the enemy ruler.

- England in the High Middle Ages?

- Recommended sites for Further Information?

- The Middle Ages.

- A Wild Christmas Ride.

- Gatto Fantasio e la Miniera Stregata (Italian Edition).

With the advent of castle-building and the extended siege, supply problems became much greater, as armies had to stay in one spot for months, or even years. Supply trains are as much a feature of Medieval warfare as they are of ancient and modern warfare. Due to the impossibility of maintaining a real front in pre-modern warfare, supplies had to be carried with the army or transported to it while under guard. However, a supply source moving with the army was necessary for any large-scale army to operate. Medieval supply trains are often found in illuminations and even poems of the period.

River and sea travel often provided the easiest way to transport supplies. During his invasion of the Levant, Richard I of England was forced to supply his army as it was marching through a barren desert. By marching his army along the shore, Richard was regularly re-supplied by ships travelling along the coast. Likewise, as in Roman Imperial times, armies would frequently follow rivers while their supplies were being carried by barges. Supplying armies by mass land-transport would not become practical until the invention of rail transport and the internal combustion engine.

The baggage train provided an alternative supply method that was not dependent on access to a water-way. However, it was often a tactical liability. Supply chains forced armies to travel more slowly than a light skirmishing force and were typically centrally placed in the army, protected by the infantry and outriders. Attacks on an enemy's baggage when it was unprotected — as for instance the French attack on the English train at Agincourt, highlighted in the play Henry V—could cripple an army's ability to continue a campaign.

This was particularly true in the case of sieges, when large amounts of supplies had to be provided for the besieging army. To refill its supply train, an army would forage extensively as well as re-supply itself in cities or supply points - border castles were frequently stocked with supplies for this purpose. A failure in logistics often resulted in famine and disease for a medieval army, with corresponding deaths and loss of morale. A besieging force could starve while waiting for the same to happen to the besieged, which meant the siege had to be lifted.

With the advent of the great castles of high medieval Europe however, this problem was typically something commanders prepared for on both sides, so sieges could be long, drawn-out affairs. Epidemics of diseases such as smallpox, cholera, typhoid, and dysentery often swept through medieval armies, especially when poorly supplied or sedentary. In a famous example, in the bubonic plague erupted in the besieging Mongol army outside the walls of Caffa, Crimea where the disease then spread throughout Europe as the Black Death. For the inhabitants of a contested area, famine often followed protracted periods of warfare, because foraging armies ate any food stores they could find, reducing or depleting reserve stores.

In addition, the overland routes taken by armies on the move could easily destroy a carefully planted field, preventing a crop the following season. Moreover, the death toll in war hit the farming labour pool particularly hard, making it even more difficult to recoup losses.

Major European wars of the Middle Ages, arranged chronologically by year begun. Perhaps the most important technological advancement for medieval warfare in Europe was the invention of the stirrup, which had been unknown to the Romans. In the Medieval period, the mounted cavalry long held sway on the battlefield. Heavily armoured, mounted knights represented a formidable foe for peasant draftees and lightly-armoured freemen. To defeat mounted cavalry, infantry used swarms of missiles or a tightly packed phalanx of men, techniques developed in Antiquity by the Greeks.

Ancient generals of Asia used regiments of archers to fend off mounted threats. Alexander the Great combined both methods in his clashes with swarming Asiatic horseman, screening the central infantry core with slingers, archers and javelin men, before unleashing his cavalry to see off attackers. The use of long pikes and densely-packed foot troops was not uncommon in Medieval times.

Flemish footmen at the Battle of the Golden Spurs met and overcame French knights in , and the Scots held their own against heavily-armoured English invaders. Louis' crusade, dismounted French knights formed a tight lance-and-shield phalanx to repel Egyptian cavalry. The Swiss used pike tactics in the late medieval period. While pikemen usually grouped together and awaited a mounted attack, the Swiss developed flexible formations and aggressive manoeuvring, forcing their opponents to respond.

The Swiss won at Morgarten, Laupen, Sempach, Grandson and Murten, and between and every leading prince in Europe hired Swiss pikemen, or emulated their tactics and weapons. The longbow was a difficult weapon to master, requiring years of use and constant practice. A skilled longbowman could shoot about 12 shots per minute. This rate of fire was far superior to competing weapons like the crossbow or early gunpowder weapons. The nearest competitor to the longbow was the much more expensive crossbow, used often by urban militias and mercenary forces.

The crossbow had greater range and penetrating power, and did not require the extended years of training. At Agincourt, thousands of French knights were brought down by armour-piercing bodkin point arrows and horse-maiming broadheads. The Welsh longbowmen decimated an entire generation of the French nobility. Since the longbow was difficult to deploy in a thrusting mobile offensive, it was best used in a defensive configuration. Bowmen were extended in thin lines and protected and screened by pits as at the Battle of Bannockburn , staves or trenches.

Sometimes bowmen were deployed in a shallow "W", enabling them to trap and enfilade their foes. The pike and the longbow put an end to the dominance of cavalry in European warfare, making the use of foot soldiers more important than they had been in recent years.