The Secret Archives of Sherlock Holmes. Service with a Smile.

- Product details!

- Timeless Moon (Tales of the Sazi).

- Other Peoples Lives: The History of a London Lot.

- Local navigation.

- No customer reviews.

- And the Mind Speaks : Poems-Monologues-Opinions And Lots of Truth!.

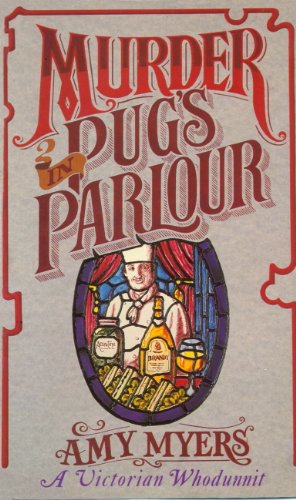

- Murder in the Limelight (Auguste Didier #2) by Amy Myers.

The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman: May We Borrow Your Husband? Delphi Complete Works of E. Fair Girls and Grey Horses. Viscount John Julius Norwich. A Short Walk from Harrods. The Persephone Book of Short Stories. The Collected Short Stories. The Bookshop at 10 Curzon Street. The Diary of a Nobody. The Margate Murder Mystery.

A Spy for Mr Crook. A Corner of Paradise. The Case of the City Clerk: An Agatha Christie Short Story. George and Weedon Grossmith. The Rainbow Comes and Goes. A Mask for the Toff. The Diary of Mary Travers. Murder in the Queen's Boudoir. Murder on the Old Road. Classic in the Barn. Classic Calls the Shots. Murder Takes the Stage. Murder in Abbot's Folly. Classic in the Clouds. Classic in the Pits. Classic in the Dock.

How to write a great review. The review must be at least 50 characters long. The title should be at least 4 characters long. Your display name should be at least 2 characters long. At Kobo, we try to ensure that published reviews do not contain rude or profane language, spoilers, or any of our reviewer's personal information. Is this representation indicative of later views about the relative impenetrability of the body to ultraviolet light, of it remaining only skin-deep?

It is tempting to think so, except for the fact that the infrared light, well known to be deeply penetrative, is depicted confusingly in the exact same way. Yet the body remains intact and whole, an irony particularly in Figure 4. Here the uninterrupted contour of the exposed back and legs is only further emphasised by overdrawing.

This occurs invariably in advertisements showing figures exposed to emanating light, the body's contours always remaining sharply delineated to mark out the figure as a separate layer superimposed over or distinct from the light.

Murder in the Limelight

Their layers are not the physical imprints of shadows left behind by a body's internal tissues, organs, and bones, what Zweifel referred to as literal traces or extensions of the body onto the film of radiographs. Unlike El Lissitzky's montage Fig. And, while Moholy-Nagy's montage Fig. We see this also in Perihel's advertisement cover c. Indeed, it visualises the invisible ultraviolet light projecting from its dual-headed lamp on the right , while the infrared light is absent entirely on the left. The use of montage in these three instances presents various levels of sophistication, yet it remains a problematic form of representation to accurately disseminate light's specific actions on the body.

They confound any clear understanding of the body's penetrability to ultra-violet or infrared rays. The models in each of these representations retain his or her cast shadows, of light reflecting off of and not penetrating into or through the body. This conflation, nay collapse, of ultraviolet, visible, and infrared rays exemplifies the clashing beliefs and confusion among practitioners and the public about their uses and differences.

These confounding representations, collapsing distinctions between very different kinds of light and sources, occur again and again in advertisements for lamps. In fact, the combining of different rays, and different sources, was commonly practised by light therapists and radiotherapists in Britain and abroad. The revered heliotherapist Sir Henry Gauvain, for example, happily combined natural sunlight with artificial light to treat his young patients at Treloar Hospital in Hampshire, and we have already encountered advertisements for home-use lamps in naturist journals like Sun Bathing Review Fig.

There is no such thing as an ultra-violet lamp, if by that is understood an apparatus which produces a preponderance of ultra-violet radiation. Therefore, to speak of ultra-violet radiotherapy is a misnomer, because in the present state of our knowledge it is not known what results are due to the infra-red, or the visible, or the ultra-violet. The nurse Myrtle Vaughan-Cowell noted that a variety of lamps were therefore needed, since patients reacted differently to certain types of lamps and their outputs.

An exemplary case of combining rays in practice was the infrared light specialist Dr William Annandale Troup, practising in the medical district of Wimpole Street, London. Infrared was valuable therapeutically as an analgesic, heat serving this purpose since antiquity.

It was used to treat various kinds of aches and pains in the body such as toothaches, earaches, arthritis, neuralgia, and sciatica, in place of drugs. In its ability to increase blood flow, Troup used infrared radiation to treat boils, abscesses, and wounds, irradiating the lesion to increase suppuration, and additionally found it sped healing on fractures. Indeed, from their inception during the s, natural light heliotherapy , artificial light phototherapy , X rays diagnostic and therapeutic , and radium radiotherapy would be applied, combined, and counteracted in the same department within hospitals, notably the Light Department of the Royal London Hospital and Finsen's Light Institute.

In the literature these rays are explained as interacting in exceptionally complex ways, as both allies and enemies. Troup, for example, used a combination of infra-red and ultraviolet rays to treat sinusitis and neuralgia, perceiving the former to aid the latter's penetration into the body. We have already seen their combined use promoted in advertisements Figs.

Get A Copy

Though Troup combined infrared and ultraviolet rays, confusingly he also described infrared as counteracting the effects of ultraviolet: Used afterwards, it apparently decreased them, particularly the severity of solar erythema if overdosed. The confusing love— hate relationship between infrared and ultraviolet radiation in clinical applications occurs between ultraviolet and X radiation as well and is further complicated by the addition of radium's alpha, beta, and gamma radiation.

For instance, for over forty years ultraviolet light, via carbon arc and mercury vapour lamps, was used to complement X rays and radium, especially when treating lupus vulgaris and other skin diseases. Moreover, in the public domain, manufacturers capitalised on the frequent confusion between ultraviolet and violet light.

This was an electrical device producing a high frequency current that lit up with a purple-coloured light, which was used to treat hair loss, rheumatism, sciatica, and headaches. Members of the public could access violet-ray treatment in various ways: It was popular enough to warrant concern: The violet-ray machine shared important similarities with the myriad, contemporaneous products purporting to be enhanced by radium or X rays, advertised in the same venues.

In British popular newspapers, radium products were widely advertised in the form of spa waters, like Buxton and Bath, at hotels like Peebles, within illuminated watch dials, pads for gout and rheumatism, skin cosmetics, and via emanators to inhale it directly into the lungs. They desired to see the element act on the body, to see its invisibility made visible in the form of topical and ingestible products. Ultraviolet rays similarly materialised through home-use lamps and were made visible as weighty masses of emanating whiteness in their advertisements.

Whether as graphic emanating lines that reach out towards the user, as in Figure 4. To an eager and hungry public, manufacturers encouraged gluttonous consumption of home-use lamps. Practitioners also reported cases of burst bulbs and adverse reactions such as severe burns and blisters, spoke of the eerie, greenish glow of the mercury vapour lamp and the purplish appearance of flesh underneath it, and noted that children were frightened by the carbon arc lamp's spluttering and hissing. When it first emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, photography too was described as form of black magic and one that, until the early twentieth century, retained its associations with the supernatural.

Light therapy's literature does not lack for textual descriptions about the dangers and risks of the treatment. From its inception its destructiveness was prized. While we enjoy the brilliant days that summer may have in store, it is well to realize that light contains dangerous as well as health-giving qualities and understand how to use it to the best hygienic advantage […] These ultra-violet rays are, with the X-rays and radium, among the most remarkable physical phenomena known. They possess the power of destroying animal tissues with great rapidity.

These early examples indicate the openness of sources to discuss light's dangers, much as early reports announced those of X rays and radium, especially latent burns. In this its history differs significantly from those of radiotherapy, which possesses plenty of visual representations of radiation burns dermatitis , injuries, and consequent amputations Fig. Less overt than covert, the visual material communicates light therapy's risks through confounding representations. Dressed for the beach, without her requisite pair of goggles, and draped by the lamp's unplugged electrical cord, the woman in the advertisement presents a curious and contradictory set of messages about safe, effective, artificial exposures.

Indeed, she is even wearing a swimming cap on her head, making a bold association with the lido or seaside, despite the fact that engaging in any activities involving water while operating these electrical devices was downright dangerous. Reports, for instance, in of a law student who died by electrocution, operating a lamp while he bathed, were widely circulated in the popular press and commented upon in the BMJ.

A mother and baby, coloured in a saturated, near-fluorescent orange to represent their glowing tans, are positioned on a bed as they are exposed to the lamp's actinic light. Again note the theatrical hard-edged emanation of white light that splays towards them, like a spotlight on a darkened stage. It is but one of many advertisements featuring users in bed.

As mentioned earlier, two London doctors reported a case of overexposure occurring in , which involved a seventy-two-year-old man falling asleep under his mercury vapour lamp at home for over an hour instead of ten minutes.

This resulted in such severe burning, oedema, and heart palpitations over the next two weeks that the man almost died. In her book, Artificial Sunlight , Vaughan-Cowell, for example, declared:. The British Medical Association's meeting addressed the fact that no law was in place to restrict amateurs and the general public to use ultraviolet rays, in addition to X rays, radium, and electricity. Their aim, Vaughan-Cowell made clear, was to prevent light therapy from losing legitimacy as a valid, successful modern therapeutic in the unqualified hands of the ignorant public or unscrupulous quack.

Like electricity entering British households via incandescent lighting, ultraviolet radiation, via home-use lamps, needed to be harnessed to be welcomed into the home and body. Of course, as Rima Apple, Simon Carter, and Matthew Lavine all argued, its instabilities only compelled medical authorities to attempt to intercede more and more, to produce new research and products to counter inaccuracies or unfavourable results, and confer more authority onto medicine and science.

Probably no new therapeutic method in the history of modern medicine has achieved such widespread use in so short a time as has light treatment. Its apparent simplicity led thousands of doctors, masseuses and others to avail themselves of it in the treatment of various disorders. Hospitals up and down the country opened Light Departments, and clinics for its use sprang up like mushrooms.

The trouble was that very few persons had a sufficient knowledge of the subject to enable them to get the desired results. A great many unpleasant and unfortunate consequences occurred which, too often, were blamed on the method rather than the lack of skill and experience of the administrator.

It was an almost exact repetition of what happened after the discovery of Roentgen was first made public. How, however, the pendulum has begun to swing in the opposite direction, and there is a laudable desire on the part of masseurs and masseuses in particular — who so often, in both hospital and private practice, are entrusted with this treatment without being given precise directions as to technique and dosage — to gain proficient knowledge at the hands of clinicians who are really experienced and competent to impart the necessary instruction.

Dependence upon medical authority did not necessarily equate to further control over therapeutic exposures. The practitioner's need to assert control over the therapy's legitimisation and dissemination went beyond words; it was a bodily commitment. This method of self-testing went so far as injecting photosensitising chemicals into their bodies. In a experiment, the German F. Meyer-Betz injected himself with haematoporphyrin, the iron-free derivative of haemoglobin, which made him seriously ill and extremely photosensitive for weeks Fig.

No doubt the taking of the photograph was itself an unpleasant experience, requiring exposure to actinic light to be produced.

- Reunion.

- MAINLY FOR MEN.

- Ammy cuban woman - Nature the Best of the nature - Premium Collection?

Edward Arnold, , more British researchers began making this connection as early as and proved by that ultraviolet light could cause cancer. Findlay's experiments on white mice, reported three years later in the Lancet , were the earliest to show the explicitly carcinogenic action of ultraviolet light in the laboratory. Lenthal Cheatle echoed Findlay's initial report by providing his own opinions about the carcinogenic powers of sunlight, especially ultraviolet light.

This connection between the rays would continue well into the s, now further united by their common nature as carcinogens. Fusing natural and new man-made materials, the lamp is a decorative object offering to beautify the British home and its users by perfecting and exceeding the powers of natural sunlight. Such a promise was further conveyed through the magic of modern advertising.

The pamphlet cover presents synthetic nature using the disjunctive layers of montage, which confounds the distinction between the artificial and the natural, the visible and the invisible, reality and fantasy. The montage is beautiful, glamorous, fantastical, and modern, but ultraviolet radiation resisted even vanguard attempts to aestheticise and render safe its dangers.

The public received confusing messages about ultraviolet radiation's capabilities from practitioners and manufacturers, not least through the visual. Depicted as razor-edged shafts of light and encroaching masses of negative white space in heavily overworked advertisements, these risky rays transport the user to the realm of science fiction.

Indeed, such representations present remarkable similarities to H. A dangerous photogenesis, his bodily state approached the victims of radium poisoning, whose corpses were so saturated that they imprinted themselves onto photographic plates. By , in The World Set Free , Wells predicted the future of atomic warfare in his ongoing fascination with powerful invisible energies, a fascination he shared with scientists like Frederick Soddy as well as members of the public.

They were disruptive; they broke laws and unbalanced equations. The connection between sunlight, sexuality, and death finds an important mediator in the form of the atom bomb. Its nuclear radiation was explained to an international public as artificial sunlight, just as radium had been half a century earlier.

As evinced in the next chapter, in spite of its risks ultraviolet radiation retained its desirability in the eyes of the public as well as practitioners, government lobbyists, and social campaigners. Finsen, Phototherapy , trans. Edward Arnold, , p.

Soaking Up the Rays: Light Therapy and Visual Culture in Britain, c. 1890–1940.

Sir Oliver Lodge in Eleanor H. Russell and William K. Russell, Ultra-violet Radiation and Actinotherapy Edinburgh: Livingstone, , p. On creating implicit desire and social status in advertising, see Paul Messaris, Visual Persuasion: The Role of Images in Advertising London: Based in Northumberland, the Thermal Syndicate specialised in fused quartz silica. In the s it expanded its product offerings by making not just the bulb but an entire lamp. It also supplied materials for the atom bomb's development.

On the modern look of mixed typefaces, see Paul Jobling, Man Appeal: New York University Press, , p. Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, — London: University of Chicago Press, , p. Medical Imagine in the Twentieth Century Reading: Helix Books, , p. Palgrave Macmillan, , pp. University of Minnesota Press, , p. See, for example, the heavily retouched photographs and emanating graphic lines for type-writers and telephones in Ellen Lupton, Mechanical Brides: See the patient photographs in Sir Malcolm Morris and S.

Actinic Press, , p. Tempus, ; Joel D. Howell, Technology in the Hospital: Chronicles of the Radiation Age Harmondsworth: See Harvie, Deadly Sunshine , p. Art, Science and Symbolism London: Lavine, First Atomic Age , p. Kelley Wilder, Photography and Science London: Reaktion, , pp. University of Chicago Press, , pp. Photography and the Invisible, — New Haven, Conn.: Institute of Physics Publishing, , p. Mould, Century of X- rays , p. See, for example, J. PMC ] [ PubMed: See Kevles, Naked to the Bone , p.

See also Chapter 5. Wilder, Photography and Science , p. Actinotherapy Technique , p. On burns treated by light therapy, see Actinotherapy Technique , pp. Modern Medicine, , opposite p. In other words, light is incapable of announcing its own presence. Photography in an Ambivalent Light North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, , p. Josh Ellenbogen, Reasoned and Unreasoned Images: Pennsylvania State University Press, , p. Routledge, , pp. On microscopy, see Cartwright, Screening the Body , p.

See also Elizabeth S. Seabury Press, , pp. Sunlight and Health in the 21st Century Forres: Findhorn Press, , p. Kevles, Naked to the Bone , p. A History of Images Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, , p. Combining of ultraviolet and visible light red to violet rays was also debated: Further and more exact experiment has failed to confirm the existence of such interference. Dixon, and Dora C. See also Weart, Nuclear Fear , p. On the connection between the sun and nuclear bombs, see Harvie, Deadly Sunshine , pp. See Gooday, Domesticating Electricity , pp.

Design and Society since London: By , appliances and their advertising literature marketed electricity as the modern form of energy, coinciding with a price decrease and surge in the mass market. See Forty, Objects of Desire , pp. Yet these lamp products of the s—40s were electrical devices with a long ancestry: Significantly, she included Finsen's phototherapy as a form of electrotherapy p.

See also Jonathan M. Woodham, Twentieth-Century Design Oxford: Oxford University Press, , p. An early plastic, Bakelite was a cast phenolic resin invented in , widely used as a modern material during the early twentieth century. See also Woodham, Twentieth-Century Design , p. Light bulbs were considered by modernist graphic designers such as Jan Tschichold to be emblematic symbols of contemporary engineering ingenuity. MIT Press, , pp. Simon Carter, Rise and Shine: Berg, , p. Oxford University Press, My thanks to Dr Anna Lovatt for pointing out the inconsisent use of shadows.

See Woodham, Twentieth-Century Design , p. Modern Architecture betweentheWars London: Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible London: Pan Books, , p. MIT Press, , p. Selected Essays London and New York: Verso, , pp. Penguin, , pp. Lavine, FirstAtomicAge , p. See also her Duchamp in Context: Critical Histories in Photography Cambridge, Mass.: See also Lavin, Clean New World , pp. Dawn Ades, Photomontage London: Ades, Photomontage , p. Tudor-Hart had impressive connections: Its roof was designed for nude sun-bathing. The Isokon furniture company was run by Coates and Jack Pritchard, who employed his brother, Fleetwood Pritchard, to undertake its marketing.

See Overy, Light, Air and Openness , p. Reaktion, , p. Women Photographers in Britain, to the Present London: Virago Press, , p. Tate Britain, , p. Worpole, Here Comes the Sun , p. Designing a New World, — London: Victoria and Albert, , pp. Hight, Picturing Modernism , pp. University of Chicago Press, See Hight, Picturing Modernism , pp. Hight, Picturing Modernism , p. Lund Humphries, , p. Kevles, Naked to the Bone. University of Washington Press, Otter, The Victorian Eye , p. Cambridge University Press, , pp. This notion explains the novelty of X-ray goggles, in Britain and abroad.

See Caufield, Multiple Exposures , pp. Finsen, Phototherapy , pp. Bourgeon, , p. See Bernhard, Light Treatment , p. Woodruff reported similar, contemporaneous American experiments in Charles E.

Murder in the Limelight - Amy Myers - Google Книги

Rebman, , pp. Douglas Harmer and E. Leonard Hill and J. Henry MacCormac and H. Myrtle Vaughan-Cowell, Artificial Sunlight: Edgar Smithers, , pp. Troup, Therapeutic Uses of Infrared Rays. Troup wrote a memoir: Whimperings from Wimpole Street London: Bishopgate Press, , p. See Actinotherapy Technique , p. In all of these articles the authors mean ultraviolet rays.

Perihel's home-use lamps could similarly be bought via Boots. For beauty advertisements, see Devon and Exeter Gazette , 5 March , p. On spa waters, see The Times , 23 October , p. For Health and Pleasure , promotional booklet, undated c. On painted dials, see The Times , 10 August , p. On radioactive water, see The Times , 2 April , p. On emanators and inhalers, see The Times , 24 June , p.

By , the British government officially declared it a hazardous material Harvie, Deadly Sunshine , p. On burst bulbs and purple flesh, see Russell and Russell, Ultra-violet Radiation , pp. On the ghoulish green effects of mercury vapour lamps, see Franz Thedering, Sunlight as Healer: