Catalog Record: The history of Virginia, in four parts | Hathi Trust Digital Library

So strong was the desire of riches, and so eager the pursuit of a rich trade, that all concern for the lives of their fellow-christians, kindred, neighbors and countrymen, weighed nothing in the comparison, though an enquiry might have been easily made when they were so near them. The merchants of London, Bristol, Exeter, and Plymouth soon perceived what great gains might be made of a trade this way, if it were well managed and colonies could be rightly settled, which was sufficiently evinced by the great profits some ships had made, which had not met with ill accidents.

Encouraged by this prospect, they joined together in a petition to King James the First, showing forth that it would be too much for any single person to attempt the settling of colonies, and to carry on so considerable a trade; they therefore prayed his majesty to incorporate them, and enable them to raise a joint stock for that purpose, and ton countenance their undertaking. His majesty did accordingly grant their petition, and by letters patents, bearing date the 10th of April, , did in one patent incorporate them into two distinct colonies, to make two separate companies, viz: And that they should extend their bounds from the said first seat of their plantation and habitation fifty English miles along the seacoast each way, and include all the lands within an hundred miles directly over against the same seacoast, and also back into the main land one hundred miles from the seacoast; and that no other should be permitted or suffered to plant or inhabit behind or on the back of them towards the main land, without the express license of the council of that colony, thereunto in writing first had and obtained.

And for the second colony, Thomas Hanham, Rawleigh Gilbert, William Parker, and George Popham, esquires, of the town of Plymouth, and all others who should be joined to them of that colony, with liberty to begin their first plantation and seat at any place upon the coast of Virginia where they should think fit, between the degrees of thirty-eight and forty five of northern latitude, with the like liberties and bounds as the first colony; provided they did not seat within an hundred miles of them.

By virtue of this patent, Capt. John Smith was sent by the London company, in December, , on his voyage with three small ships, and a commission was given to him, and to several other gentlemen, to establish a colony, and to govern by a president, to be chosen annually, and council, who should be invested with sufficient authorities and powers. And now all things seemed to promise a plantation in good earnest. Providence seemed likewise very favorable to them, for though they designed only for that part of Virginia where the hundred and fifteen were left, and where there is no security of harbor, yet after a tedious voyage of passing the old way again, between the Caribbee islands and the main, he, with two of his vessels, luckily fell in with Virginia itself, that part of the continent now so called, anchoring in the mouth of the bay of Chesapeake; and the first place they landed upon was the southern cape of that bay; this they named Cape.

Henry, and the northern Cape Charles, in honor of the king's two eldest sons; and the first great river they searched, whose Indian name was Powhatan, they called James river, after the king's own name. Before they would make any settlement here, they made a full search of James river, and then by an unanimous consent pitched upon a peninsula about fifty miles up the river, which, besides the goodness of the soil, was esteemed as most fit, and capable to be made a place both of trade and security, two-thirds thereof being environed by the main river, which affords good anchorage all along, and the other third by a small narrow river, capable of receiving many vessels of an hundred ton, quite up as high as till it meets within thirty yards of the main river again, and where generally in spring tides it overflows into the main river, by which means the land they chose to pitch their town upon has obtained the name of an island.

In this back river ships and small vessels may ride lashed to one another, and moored ashore secure from all wind and weather whatsoever. The town, as well as the river, had the honor to be called by King James' name. The whole island thus enclosed contains about two thousand acres of high land, and several thousands of very good and firm marsh, and is an extraordinary good pasture as any in that country.

By means of the narrow passage, this place was of great security to them from the Indian enemy; and if they had then known of the biting of the worm in the salts, they would have valued this place upon that account also, as being free from that mischief. They were no sooner settled in all this happiness and security, but they fell into jars and dissensions among themselves, by a greedy grasping at the Indian treasure, envying and overreaching on another in that trade. After five weeks stay before this town, the ships returned home again, leaving one hundred and eight men settled in the form of government before spoken of.

The Indians were the same there as in all other places, at first very fair and friendly, though afterwards they gave great proofs of their deceitfulness. However, by the help of the Indian provisions, the English chiefly subsisted till the return of the ships the next year, when two vessels were sent thither full freighted with men and provisions for supply of the plantation, one of which only arrived directly, and the other being beat off to the Caribbee islands, did not arrive till the former was sailed again for England.

In the interval of these ships returning from England, the English had a very advantageous trade with the Indians, and might have made much greater gains of it, and managed it both to the greater satisfaction of the Indians, and the greater ease and security of themselves, if they had been under any rule, or subject to any method in trade, and not left at liberty to outvie or outbid one another, by which they not only cut short their own profit, but created jealousies and disturbances among the Indians, by letting one have a better bargain than another; for they being unaccustomed to barter, such of them as had been hardest dealt by in their commodities, thought themselves cheated and abused; and so conceived a grudge against the English in general, making it a national quarrel; and this seems to be the original cause of most of their subsequent misfortunes by the Indians.

What also gave a greater interruption to this trade, was an object that drew all their eyes and thoughts aside, even from taking the necessary care for their preservation, and for the support of their lives, which was this: They found in a neck of land, on the back of Jamestown island, a fresh stream of water springing out of a small bank, which washed down with it a yellow sort of dust isinglass, which being cleansed aby the fresh streaming of the water, lay shining in the bottom of that limpid element, and stirred up in them an unseasonable and inordinate desire after riches; for they taking all to be gold that glittered, run into the utmost distraction,.

For, by their negligence, they were reduced to an exceeding scarcity of provisions, and that little they had was lost by the burning of their town, while all hands were employed upon this imaginary golden treasure; so that they were forced to live for some time upon the wild fruits of the earth, and upon crabs, muscles, and such like, not having a day's provision before-hand; as some of the laziest Indians, who have no pleasure in exercise, and wont be at the pains to fish and hunt: And, indeed, not so well as they neither; for by this careless neglecting of their defense against the Indians, many of them were destroyed by that cruel people, and the rest durst not venture abroad, but were forced to be content with what fell just into their mouths.

In this condition they were, when the first ship of the two before mentioned came to their assistance, but their golden dreams overcame all difficulties; they spoke not, nor thought of anything but gold, and that was all the lading that most of them were willing to take care for; accordingly they put into this ship all the yellow dirt they had gathered, and what skins and furs they had trucked for, and filling her up with cedar, sent her away. After she was gone, the other ship arrived, which they stowed likewise with this supposed gold dust, designing never to be poor again; filling her up with cedar and clap-board.

Those two ships being thus dispatched, they made several discoveries in the James river and up Chesapeake bay, by the undertaking and management of Captain John Smith; and the year was the first year in which they gathered Indian corn of their own planting. While these discoveries were making by Captain Smith, matters run again into confusion in Jamestown, and several. Thus the English continued to give themselves as much perplexity by their own distraction as the Indians did by their watchfulness and resentments.

Anno , John Laydon and Anna Burrows were married together, the first Christian marriage in that part of the world; and the year following the plantation was increased to near five hundred men. This year Jamestown sent out people, and made two other settlements; one at Nansemond in James river, above thirty miles below Jamestown, and the other at Powhatan, six miles below the falls of James river, which last was bought of Powhatan for a certain quantity of copper, each settlement consisting of about a hundred and twenty men.

Some small time after another was made at Kiquotan by the mouth of James river. In the meanwhile the treasurer, council and company of Virginia adventurers in London, not finding that return and profit from the adventurers they expected, and rightly judging that this disappointment, as well as the idle quarrels in the colony, proceeded from a mismanage of government, petitioned his majesty, and got a new patent with leave to appoint a governor.

Download This eBook

Upon this new grant they sent out nine ships, and plentiful supplies of men and provisions, and made three joint commissioners or governors in equal power, viz: They agreed to go all together in one ship. This ship, on board of which the three governors had embarked, being separated from the rest, was put to great distress in a severe storm; and after three days and nights constant bailing and pumping, was at last cast ashore at Bermudas, and there staved, but by good providence the company was preserved. Notwithstanding this shipwreck, and extremity they were put to, yet could not this common misfortune make them agree.

The best of it was, they found plenty of provisions in that island, and no Indians to annoy them. But still they quarreled amongst themselves, and none more than the two Knights; who made their parties, built each of them a cedar vessel, one called the Patience, the other the Deliverance, and used what they gathered of.

While these things were acting in Bermuda, Capt. Smith being very much burnt by the accidental firing of some gun-powder, as he was upon a discovery in his boat, was forced for his cure sake, and the benefit of a surgeon, to take his passage for England, in a ship that was then upon the point of sailing. And yet, for all this, they continued their disorders, wasting their old provisions, and neglecting to gather others; so that they who remained alive, were all near famished, having brought themselves to that pass, that they durst not stir from their own doors to gather the fruits of the earth, or the crabs and muscles from the water-side: They continued in these scanty circumstances, till they were at last reduced to such extremity, as to eat the.

Thus, a few months indiscreet management brought such an infamy upon the country, that to this day it cannot be wiped away. And the sicknesses occasioned by this bad diet, or rather want of diet, are unjustly remembered to the disadvantage of the country, as a fault in the climate; which was only the foolishness and indiscretion of those who assumed the power of governing. I call it assumed, because the new commission mentioned, by which they pretended to be of the council, was not in all this time arrived, but remained in Bermuda with the new governors.

Here, I cannot but admire the care, labor, courage and understanding, that Capt. John Smith showed in the time of his administration; who not only founded, but also preserved all these settlements in good order, while he was amongst them; and, without him, they had certainly all been destroyed, either by famine, or the enemy long before; though the country naturally afforded subsistence enough, even without any other labor than that of gathering and preserving its spontaneous provisions.

For the first three years that Capt. Smith was with them, they never had in that whole time, above six months English provisions. But as soon as he had left them to themselves, all went to ruin; for the Indians had no longer any fear for themselves, or friendship for the English.

And six months after this gentleman's departure, the men that he had left were reduced to threescore; and they, too, must of necessity, have starved, if their relief had been delayed a week longer at sea. In the mean time, the three governors put to sea from Burmuda, in their two small vessels, with their company, to the number of one hundred and fifty, and in fourteen days, viz.: Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Summers, and Captain Newport, the governors, were very compassionate of their condition, and called a council, wherein they informed them, that they had but sixteen days provision aboard; and therefore desired to know their opinion, whether they would venture to sea under such a scarcity; or, if they resolved to continue in the settlement, and take their fortunes, they would stay likewise, and share the provisions among them; but desired that their determination might be speedy.

They soon came to the conclusion of returning for England; but because their provisions were short, they resolved to go by the banks of Newfoundland, in hopes of meeting with some of the fishermen, this being now the season, and dividing themselves among their ships, for the greater certainty of provision, and for their better accommodation. According to this resolution, they all went aboard, and fell down to Hog Island, the 9th of June, at night, and the next morning to Mulberry Island Point, which is eighteen miles below Jamestown, and thirty above the mouth of the river; and there they spied a long boat, which the Lord Delawarr who was just arrived with three ships, had sent before him up the river sounding the channel.

His lordship was made sole governor, and was accompanied by several gentlemen of condition. He caused all the men to return again to Jamestown; re-settled them with satisfaction, and staid with them till March following; and then being very sick, he returned for England, leaving about two hundred in the colony. On the 10th of May, , Sir Thomas Dale being then made governor, arrived with three ships, which brought supplies of men, cattle and hogs. He found them growing again into the like disorders as before, taking no care to plant corn, and wholly relying upon their store, which then had but three months provision in it.

In the beginning of September he settle a new town at Arrabattuck, about fifty miles above Jamestown, paling in the neck above two miles from the point, from one reach of the river to the other. And also run a palisado on the other side of the river, at Coxendale, to seccure their hogs.

Anno , two ships more arrived with supplies; and Capt. Argall, who commanded one of them, being sent in her to Patowmeck to buy corn, he there met with Pocahontas, the excellent daughter of Powhatan; and having prevailed with her to come aboard to a treat, he detained her prisoner, and carried her to Jamestown, designing to make peace with her father by her release; but on the contrary, that prince resented the affront very highly; and although he loved his daughter with all imaginable tenderness, yet he would not be brought to terms by that unhandsome treachery; till about two years after a marriage being proposed between Mr.

John Rolfe, an English gentleman, and this lady; which Powhatan taking to be a sincere token of friendship, he vouchsafed to consent to it, and to conclude a peace, though he would not come to the wedding. Pocahontas being thus married in the year , a firm peace was concluded with her father. Both the English and Indians thought themselves entirely secure and quiet. This bought in the Chickahominy Indians also, though not out of any kindness or respect to the English, but out of fear of being, by their assistance, brought under. Powhatan's absolute subjection, who used now and then to threaten and tyrannize over them.

Rolfe and his wife Pocahontas, who upon the marriage, was christened, and called Rebecca. George Yardly deputy governor during his absence, the country being then entirely at peace; and arrived at Plymouth the 12th of June. John Smith was at that time in England, and hearing of the arrival of Pocahontas at Portsmouth, used all the means he could to express his gratitude to her, as having formerly preserved his life by the hazard of her own; for, when by the command of her father, Capt.

Smith's head was upon the block to have his brains knocked out, she saved his head by laying hers close upon it. He was at that time suddenly to embark for New England, and fearing he should sail before she got to London, he made an humble petition to the Queen in her behalf, which I here choose to give you in his own words, because it will save me the story at large.

The love I bear my God, my king, and country, hath so often emboldened me in the worst of extreme dangers, that now honestly doth constrain me to presume thus far beyond myself, to present your majesty this short discourse. If ingratitude be a deadly poison to all honest virtues, I must be guilty of that crime, if I should omit any means to be thankful.

I being the first Christian this proud king and his grim attendants ever saw, and thus enthralled in their barbarous power; I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want, that was in the power of those my mortal foes to prevent, notwithstanding all their threats. After some six weeks fatting amongst those savage courtiers, at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine, and not only that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown, where I found about eight and thirty miserable, poor and sick creatures, to keep possession for all those large territories of Virginia.

Such was the weakness of this poor commonwealth, as had not the savages fed us, we directly had starved. And this relief, most gracious queen, was commonly brought us by this lady Pocahontas, notwithstanding all these passages, when unconstant fortune turned our peace to war, this tender virgin would still not spare to dare to visit us; and by her our jars have been oft appeased, and our wants still supplied. Were it the policy of her father thus to employ her, or the ordinance of God thus to make her his instrument, or her extrordinary affection to our nation, I know not: Jamestown, with her wild train, she as freely frequented as her father's habitation; and during the time of two or.

Since then, this business having been turned and varied by many accidents from what I left it, it is most certain, after a long and troublemsome war, since my departure, betwixt her father and our colony, all which time she was not heard of, about two years after she herself was taken prisoner, being so detained near two years longer, the colony by that means was relieved, peace concluded, and at last, rejecting her barbarous condition, she was married to an English gentleman, with whom at this present she is in England.

- Find a copy in the library;

- The Murder Quadrille.

- Chemistry: Notable Research and Discoveries (Frontiers of Science)!

The first Christin ever of that nation; the first Virginian ever spake English, or had a child in marriage by an Englishman--a matter surely, if my meaning be truly considered and well understood, worthy a prince's information. Thus, most gracious laby, I have related to your majesty, what at your best leisure, our approved histories will recount to you at large, as done in the time of your majesty's life; and however this might be presented you from a more worthy pen, it cannot from a more honest heart. As yet, I never begged anything of the State; and it is my want of ability, and her exceeding desert; your birth, means, and authority; her birth, virtue, want and simplicity, doth make me thus bold, humbly to beseech your majesty to take this knowledge of her, though it be from one so unworthy to be the reporter as myself; her husband's estate not being able to make her fit to attend your majesty.

The most and least I can do, is to tell you this, and the rather because of her being of so great a spirit, however her stature. If she should not be well received, seeing this kingdom may rightly have a kingdom by her means; her present love to us and Christianity, might turn to such scorn and fury, as to divert all this good to the. Where finding that so great a queen should do her more honor than she can imagine, for having been kind to her subjects and servants, 'twould so ravish her with content, as to endear her dearest blood, to effect that your majesty and all the king's honest subjects most earnestly desire.

This account was presented to her majesty, and graciously received. Smith sailed for New England, the Indian princess arrived at London, and her husband took lodgings for her at Branford, to be a little out of the smoke of the city, whither Capt. Smith, with some of his friends, went to see her and congratulate her arrival, letting her know the address he had made to the queen in her favor.

Till this lady arrived in England, she had all along been informed that Captain Smith was dead, because he had been diverted from that colony by making settlements in the second plantation, now called New England; for which reason, when she saw him, she seemed to think herself much affronted, for that they had dared to impose so gross an untruth upon her, and at first sight of him turned away. It cost him a great deal of entreaty, and some hours attendance, before she would do him the honor to speak to him; but at last she was reconciled, and talked freely to him.

She put him in mind of her former kindnesses, and then upbraided him for his forgetfulness of her, showing by her reproaches, that even a state of nature teacher to abhor ingratitude. She had in her retinue a Werowance, or great man of her own nation, whose name was Uttamaccomack. This man had orders from Powhatan, to count the people in England, and give him an account of their number. He desired him to count the stars in the sky, the leaves upon the trees, and the sand on the seashore, for so many people he said were in England.

Pocahontas had many honors done her by the queen upon account of Captain Smith's story; and being introduced by the Lady Delawarr, she was frequently admitted to wait on her majesty, and was publicly treated as a prince's daughter; she was carried to many plays, balls, and other public entertainments, and very respectfully received by all the ladies about the court.

Smith had given of her. In the meanwhile, she gained the good opinion of everybody so much, that the poor gentleman, her husband, had like to have been called to an account, for presuming to marry a princess royal without the king's consent; because it had been suggested that he had taken advantage of her, being a prisoner, and forced her to marry him. But upon a more perfect representation of the matter, his majesty was pleased at last to declare himself satisfied. But had their true condition here been known, that pother had been saved.

Everybody paid this young lady all imaginable respect; and it is supposed, she would have sufficiently acknowledged those favors, had she lived to return to her own country, by bringing the Indians to have a kinder disposition towards the English. But upon her return she was unfortunately taken ill at Gravesend, and died in a few days after, giving great testimony all the time she lay sick, of her being a very good Christian. She left issue one son, named Thomas Rolfe, whose posterity is at this.

Captain Yardly made but a very ill governor, he let the buildings and forts go to ruin; not regarding the security of the people against the Indians, neglecting the corn, and applying all hands to plant tobacco, which promised the most immediate gain. In this condition they were when Capt. Samuel Argall was sent thither governor, Anno , who found the number of people reduced to little more than four hundred, of which not above half were fit for labor.

In the meanwhile the Indians mixing among them, got experience daily in fire arms, and some of them were instructed therein by the English themselves, and employed to hunt and kill wild fowl for them. So great was their security upon this marriage; but governor Argall not liking those methods, regulated them on his arrival, and Capt. Yardly returned to England. Governor Argall made the colony flourish and increase wonderfully, and kept them in great plenty and quiet.

The next year, viz.: Anno , the Lord Delawarr was sent over again with two hundred men more for the settlement, with other necessaries suitable: By which means the government there still continued in the hands of Capt. Powhatan died in April the same year, leaving his second brother Itopatin in possession of his empire, prince far short of the parts of Oppechancanough, who by some was said to be his elder brother, and then king of Chickahomony; but he having debauched them from the allegiance of Powhatan, was disinherited by him.

This Oppechancanough was a cunning and brave prince, and soon grasped all the empire to himself. But at first they jointly renewed the peace with the English, upon the accession of Itopatin to the crown. Governor Argall flourishing thus under the blessings of peace and plenty, and having no occasion of fear or disturbance from the Indians, sought new occasions of encouraging the plantation. To that end, he intended a coasting voyage to the northward, to view the places where the English ships had so often laded; and if he missed them, to reach the fisheries on the banks of Newfoundland, and so settle a trade and correspondence either with the one or the other.

In accomplishing whereof, as he touched at Cape Cod, he was informed by the Indians, that some white people like him were come to inhabit to the northward of them, upon the coast of their neighboring nations. Argall not having heard of any English plantation that way, was jealous that it might be as it proved, the people of some other nation. And being very zealous for the honor and benefit of England, he resolved to make search according to the information he had received, and see who they were. Accordingly he found the settlement, and a ship riding before it. This belonged to some Frenchmen, who had fortified themselves upon a small mount on the north of New England.

His unexpected arrival so confounded the French, that they could make no preparation for resistance on board their ship; which Captain Argall drew so close to, that with his small arms he beat all the men from the deck, so that they could not use their guns, their ship having only a single deck. Among others, there were two Jesuits on board, one of which being more bold than wise, with all that disadvantage, endeavored to fire one of their cannon, and was shot dead for his pains.

Captain Argall having taken the ship, landed and went before the fort, summoning it to surrender. The garrison asked time to advise; but that being denied them, they stole privately away, and fled into the woods. Upon this, Captain Argall entered the fort, and lodged there that night; and the next day the French came to him, and surrendered themselves. It seems the king of France had. He used them very well, and suffered such as had a mind to return to France, to seek their passage among the ships of the fishery; but obliged them to desert this settlement.

And those that were willing to go to Virginia, he took with him. These people were under the conduct of two Jesuits, who upon taking a pique against their governor in Acadia, named Biencourt, had lately separated from a French settlement at Port Royal, lying in the bay, upon the south-west part of Acadia. As Governor Argall was about to return to Virginia, father Biard, the surviving Jesuit out of malice to Biencourt, told him of this French settlement at Port Royal, and offered to pilot him to it; which Governor Argall readily accepted of.

With the same ease, he took that settlement also; where the French had sowed and reaped, built barns, mills, and other conveniences, which Captain Argall did no damage to; but unsettled them, and obliged them to make a desertion from thence. He gave these the same leave he had done the others, to dispose of themselves; some whereof returned to France, and others went to settle up the river of Canada.

After this Governor Argall returned satisfied with the provision and plunder he had got in those two settlements. The report of these exploits soon reached England; and whether they were approved or no, being acted without particular direction, I have not learned; but certain it is, that in April following there arrived a small vessel, which did not stay for anything, but took on board Governor Argall, and returned for England.

Nathaniel Powel deputy; and soon after Capt. Yardly being knighted, was sent governor thither again.

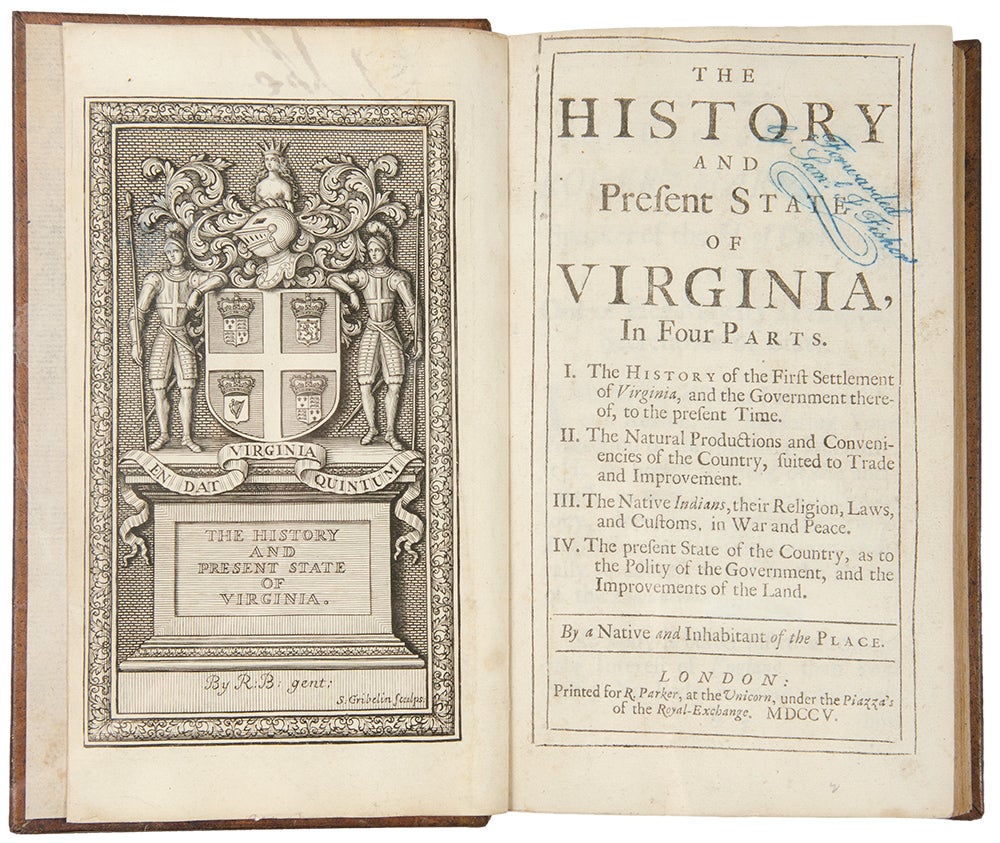

The History of Virginia, in Four Parts by Robert Beverley

Very great supplies of cattle and other provisions were sent there that year, and likewise or men. They resettled all their old plantations that had been deserted, made additions to the number of the council, and. These burgesses met the governor and council at Jamestown in May, , and sat in consultation in the same house with them, as the method of the Scots Parliament is, debating matters for the improvement and good government of the country. This was the first general assembly that was ever held there. I heartily wish though they did not unite their houses again, they would, however, unite their endeavors and affections for the good of the country.

In August following, a Dutch man-of-war landed twenty negroes for sale; which were the first of that kind that were carried into the country. This year they bounded the corporations, as they called them: But there does not remain among the records any on grant of these corporations. There is entered a testimony of Governor Argall, concerning the bounds of the corporation of James City, declaring his knowledge thereof; and this is one of the new transcribed books of record.

But there is not to be found on word of the charter or patent itself of this corporation. Then also, they apportioned and laid our lands in several allotments, viz.: The people knew their own property, and having the encouragement of working for their own advantage, many became very industrious, and began to vie one with another, in planting, building, and other improvements.

Two gentlemen went over as deputies to the company, for the management of their lands, and those of the college. All thoughts of danger from the Indians were laid aside. Several great gifts were made to the church and college, and for the bringing up young Indians at school. Forms were made, and rules appointed. And all there then began think themselves the happiest people in the world.

Thus Virginia continued to flourish and increase, great supplies continually arriving, and new settlements being made all over the country. A salt work was set up at Cape Charles, on the Eastern Shore; and an iron work at Falling Creek, in James river, where they made proof of good iron ore, and brought the whole work so near a perfection, that they writ word to the company in London, that they did not doubt but to finish the work, and have plentiful provision of iron for them by the next Easter.

At that time the fame of the plenty and riches, in which the English lived there, was very great. And Sir George Yardly now had all the appearance of making amends for the errors of his former government. Nevertheless he let them run into the same sleepiness and security as before, neglecting all thoughts of a necessary defense, which laid the foundation of the following calamities. But the time of his government being near expired, Sir Francis Wyat, then a young man, had a commission to succeed him.

The people began to grow numerous, thirteen hundred settling there that year; which was the occasion of making so much tobacco, as to overstock the market. Wherefore his majesty, out of pity to the country, sent his commands, that they should not suffer their planters to make above one hundred pounds of tobacco per man; for the market was so low, that he could not afford to give them above three shillings the pound for it. He advised them rather to turn their spare time towards providing corn and stock, and towards the making of potash, or other manufacturers. It was October, , that Sir Francis Wyat arrived governor, and in November, Captain Newport arrived with fifty men, imported at his own charge, besides passengers; and made a plantation on Newport's News, naming it.

The governor made a review of all the settlements, and suffered new ones to be made, even as far as Potomac river. This ought to be observed of the Eastern Shore Indians, that they never gave the English any trouble, but courted and befriended them from first to last. Perhaps the English, by the time they came to settle those parts, had considered how to rectify their former mismanagement, and learned better methods of regulating their trade with the Indians, and of treating them more kindly than at first. Anno , inferior courts were first appointed by the general assembly, under the name of county courts, for trial of minute causes; the governor and council still remaining judges of the supreme court of the colony.

In the meantime, by the great increase of people, and the long quiet they had enjoyed among the Indians, since the marriage of Pocahontas, and the accession of Oppechancanough to the imperial crown, all men were lulled into a fatal security, and became everywhere familiar with the Indians, eating, drinking, and sleeping amongst them; by which means they became perfectly acquainted with all our English strength, and the use of our arms--knowing at all times, when and where to rind our people; whether at home, or in the woods; in bodies, or dispersed; in condition of defense, or indefensible.

This exposing of their weakness gave them occasion to think more contemptibly of them, than otherwise, perhaps, they would have done; for which reason they became more peevish, and more hardy to attempt anything against them. Thus upon the loss of one of their leading men, a war captain, as they call him, who was likewise supposed to be justly killed, Oppechancanough took affront, and in revenge laid the plot of a general massacre of the English, to be executed on he 22d of March, , a little before noon, at a time when our men were all at work abroad in their plantations, dispersed and unarmed.

This hellish contrivance was to take effect upon all the. The Indians had been made so familiar with the English, as to borrow their boats and canoes to cross the river in, when they went to consult with their neighboring Indians upon this execrable conspiracy. And to color their design the better, they brought presents of deer, turkeys, fish and fruits to the English the evening before. The very morning of the massacre, they came freely and unarmed among them, eating with them, and behaving themselves with the same freedom and friendship as formerly, till the very minute they were to put their plot in execution.

Then they fell to work all at once everywhere, knocking the English unawares on the head, some with their hatchets, which they call tomahawks, others with the hoes and axes of the English themselves, shooting at those who escaped the reach of their hands; sparing neither age nor sex, but destroying man, woman, and child, according to their cruel way of leaving none behind to bear resentment.

But whatever was not done by surprise that day, was left undone, and many that made early resistance escaped. By the account taken of the Christians murdered that morning, they were found to be three hundred and forty-seven, most of them falling by their own instruments, and working tools.

The massacre had been much more general, had not this plot been providentially discovered to the English some hours before the execution. Two Indians that used to be employed by the English to hunt for them, happened to lie together, the night before the massacre, in an Englishmen's house, where one of them was employed. The Indian that was the guest fell to persuading the other to rise and kill his master, telling him, that he would do the same by his own the next day.

Whereupon he discovered the whole plot that was designed to be executed on the morrow. But the other, instead of entering into the plot, and murdering his master, got. The master hereupon arose, secured his own house, and before day got to Jamestown, which, together with such plantations as could receive notice time enough, were saved by this meas; the rest, as they happened to be watchful in their defense, also escaped; but such as were surprised, were massacred. Captain Croshaw in his vessel at Potomac, had notice also given him by a young Indian, by which means he came off untouched.

The occasion upon which Oppechancanough took affront was this. The war captain mentioned before to have been killed, was called Nemattanow. He was an active Indian, a great warrior, and in much esteem among them; so much, that they believed him to be invulnerable, and immortal, because he had been in very many conflicts, and escaped untouched from them all. He was also a very cunning fellow, and took great pride in preserving and increasing this their superstition concerning him, affecting everything that was odd and prodigious, to work upon their admiration.

For which purpose he would often dress himself up with feathers after a fantastic manner, and by much use of that ornament, obtained among the English the nickname of Jack of the feather. This Nemattanow coming to a private settlement of one Morgan, who had several toys which he had a mind to, persuaded him to go to Pamunky to dispose of them. At last Morgan yielded to his persuasion; but was no more heard of; and it is believed, that Nemattanow killed him by the way, and took away his treasure. For within a few days this Nemattanow returned to the same house with Morgan's cap upon his head; where he found two sturdy boys, who asked for their master.

He very frankly told them he was dead. But they, knowing the cap again, suspected. As he was dying, he earnestly pressed the boys to promise him two things. First, that they would not tell how he was killed; and, secondly, that they would bury him among the English. So great was the pride of this vain heathen, that he had no other thoughts at his death, but the ambition of being esteemed after he was dead, as he had endeavored to make them believe of him while he was alive, viz. He imagined, that being buried among the English perhaps might conceal his death from his own nation, who might think him translated to some happier country.

Thus he pleased himself to the last gasp with the boys' promises to carry on the delusion. This was reckoned all the provocation given to that haughty and revengeful man Oppechancanough, to act this bloody tragedy, and to take indefatigable pains to engage in so horrid villainy all the kings and nations bordering upon the English settlements, on the western shore of Chesapeake.

This gave the English a fair pretense of endeavoring the total extirpation of the Indians, but more especially of Oppechancanough and his nation. Accordingly, they set themselves about it, making use of the Roman maxim, faith is not to be kept with heretics to obtain their ends. For, after some months fruitless pursuit of them, who could too dexterously hide themselves in the woods, the English pretended articles of peace, giving them all manner of fair words and promises of oblivion.

They designed thereby as their own letters now on record, and their own actions thereupon prove to draw the Indians back, and entice them to plant their corn on their habitations nearest adjoining to the English, and then to cut it up, when the summer. And the English did so far accomplish their ends, as to bring the Indians to plant their corn at their usual habitations, whereby they gained an opportunity of repaying them some part of the debt in their own coin, for they fell suddenly upon them, cut to pieces such of them as could not make their escape, and afterwards totally destroyed their corn.

Another effect of the massacre of the English, was the reducing all their settlements again to six or seven in number, for their better defense.

Find a copy online

Besides, it was such a disheartening to some good projects, then just advancing, that to this day they have never been put in execution, namely, the glasshouses in Jamestown, and the iron work at Falling Creek, which has been already mentioned. The massacre fell so hard upon this last place, that no soul was saved but a boy and a girl, who with great difficulty hid themselves. The superintendent of this iron work had also discovered a vein of lead ore, which he kept private, and made use of it to furnish all the neighbors with bullets and shot.

But he being cut off with the rest, and the secret not having been communicated, this lead mine could never after be found, till Colonel Byrd, some few years ago, prevailed with an Indian, under pretense of hunting, to give him a sign by dropping his tomahawk at the place, he not daring publicly to discover it, for fear of being murdered. The sign was accordingly given, and the company at that time found several pieces of good lead ore upon the surface of the ground, and marked the trees thereabouts.

I know not by what witchcraft it happens, but no mortal to this day could ever find that place again, though it be upon part of the Colonel's own possessions. And so it rests, till time and thicker settlements discover it. Thus, the company of adventurers having, by those frequent acts of mismanagement, met with vast losses and misfortunes, many grew sick of it and parted with their.

But the chief design of all parties concerned, was to fetch away the treasure from thence, aiming more at sudden gain, than to form any regular colony, or establish a settlement in such a manner as to make it a lasting happiness to the country. Several gentlemen went over upon their particular stocks, separate from that of the company, with their won servants and goods, each designing to obtain land from the government, as Captain Newport had done, or at least to obtain patents, according to the regulations for granting lands to adventurers.

Others sought their grants of the company in London, and obtained authorities and jurisdictions, as well as land, distinct from the authority of the government, which was the foundation of great disorder, and the occasion of their following misfortunes. Among others, one Captain Martin, having made very considerable preparations toward settlement, obtained a suitable grant of land, and was made of the council there.

But he, grasping still at more, hankered after dominion, as well as possession, and caused so many differences, that at last he put all things into distraction, insomuch that the Indians, still seeking revenge, took advantage of these dissensions, and fell foul again on the English, gratifying their vengeance with new bloodshed.

The fatal consequences of the company's maladministration cried so loud, that king Charles the first, coming to the crown of England, had a tender concern for the poor people that had been betrayed thither and lost. Upon which consideration he dissolved the company in the year , reducing the county and government into this own immediate direction, appointing the governor and council himself, and ordering all patents and processes to issue in his own name, reserving to himself a quit-rent of two shillings for every hundred acres of land, and so pro rata.

The country being thus taken into the king's hands, his majesty was please to establish the constitution to be by a governor, council and assembly, and to confirm the former methods and jurisdictions of the several courts, as they had been appointed in the year , and placed the last resort in the assembly. He likewise confirmed the rules and orders made by the first assembly for apportioning the land, and granting patents to particular adventurers.

This was a constitution according to their hearts desire, and things seemed now to go on in a happy course for encouragement of the colony. People flocked over thither apace; every one took up land by patent to his liking; and, not minding anything but to be masters of great tracts of land, they planted themselves separately on their several plantations. Nor did they fear the Indians, but kept them at a greater distance than formerly. And they for their part, seeing the English so sensibly increase in number, were glad to keep their distance and be peaceable.

This liberty of taking up land, and the ambition each man had of being lord of a vast, though unimproved territory, together with the advantage of the many rivers, which afford a commodious road for shipping at every man's door, has made the country fall into such an unhappy settlement and course of trade, that to this day they have not any one place of cohabitation among them, that may reasonably bear the name of a town.

The constitution being thus firmly established, and continuing its course regularly for some time, people began to lay aside all fears of any future misfortunes. Several gentlemen of condition went over with their whole families-- some for bettering their estates--others for religion, and other reasons best known to themselves.

Among those, the noble Caecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore, a Roman Catholic, thought, for the more quite exercise of his religion, to retire, with his family, into that new world. For this purpose he went to Virginia, to try how he liked the place. But the people there looked upon him with an evil eye on account of his religion, for which alone he sought this retreat, and by their ill treatment discouraged him from settling in that country.

Upon that provocation, his lordship resolved upon a farther adventure. And finding land enough up he bay of Chesapeake, which was likewise blessed with many brave rivers, and as yet altogether uninhabited by the English, he began to think of making a new plantation of his own. And for his more certain direction in obtaining a grant of it, he undertook a journey northward, to discover the land up the bay, and observe what might most conveniently square with his intent.

His lordship finding all things in this discovery according to his wish, returned to England. And because the Virginia settlements at that time reached no farther that the south side of Potomac river, his lordship got a grant of the propriety of Maryland, bounding it to the south by Potomac river, on the western shore; and by an east line from Point Lookout, on the eastern shore; but died himself before he could embark for the promised land.

Maryland had the honor to receive its name from queen Mary, royal consort to king Charles the first. The old Lord Baltimore being thus taken off, and leaving his designs unfinished, his son and heir, in the year , obtained a confirmation of the patent to himself, and went over in person to plant his new colony. By this unhappy accident, a country which nature had so well contrived for one, became two separate governments. This produced a most unhappy inconvenience to both; for, these two being the only countries under the dominion of England that plant tobacco in any quantity, the ill consequences to both is, that when one colony goes about to prohibit the trash, or mend the staple of that commodity, to help the market, then the other, to take advantage of that market, pours into England all they can make, both good and bad, with out distinction.

This is very injurious to the other colony, which had voluntarily suffered so great a diminution in the quantity, to mend the quality; and this is notoriously manifested from that incomparable Virginia law, appointing sworn agents to examine their tobacco. Neither was this all the mischief that happened to Virginia upon this grant; for the example of it had dreadful consequences, and was in the end one of the occasions of another massacre by the Indians, For this precedent of my Lord Baltimore's grant, which entrenched upon the charters and bounds of Virginia, was hint enough for other courtiers, who never intended a settlement as my lord did to find out something of the same kind to make money of.

This was the occasion of several very large defalcations from Virginia with in a few years afterwards, which was forwarded and assisted by the contrivance of the Governor, Sir John Harvey, insomuch that not only the land itself, quit-rents and all, but the authorities and jurisdictions that belonged to that colony were given away--nay, sometimes in those grants he included the very settlements that had been before made.

As this gentleman was irregular in this, so he was very unjust and arbitrary in his other methods of government. He exacted with rigor the fines and penalties, which the unwary assemblies of those times had given chiefly to himself, and was so haughty and furious to the council, and the best gentlemen of the country, that his tyranny grew at last insupportable; so that in the year , the. This news being brought to king Charles the first, his majesty was very much displeased; and, without hearing anything, caused him to return governor again. But by the next shipping he was graciously pleased to change him, and so made amends for this man's maladministration, by sending the good and just Sir William Berkeley to succeed him.

While these things were transacting, there was so general a dissatisfaction, occasioned by the oppressions of Sir John Harvey, and the difficulties in getting him out, that the whole colony was in confusion. The subtle Indians, who took all advantages, resented the encroachments upon them by his grants. They saw the English uneasy and disunited among themselves, and by the direction of Oppechancanough, their king, laid the ground work of another massacre, wherein, by surprise, they cut off near five hundred Christians more.

But this execution did not take so general effect as formerly, because the Indians were not so frequently suffered to come among the inner habitations of the English; and, therefore, the massacre fell severest on the south side of James river, and on the heads of the other rivers, but chiefly of York river, where this Oppechancanough kept the seat of his government.

Oppechancanough was a man of large stature, noble presence, and extraordinary parts. Though he had no advantage of literature, that being nowhere to be found among the American Indians yet he was perfectly skilled in the art of governing his rude countrymen. He caused all the Indians far and near to dread his name, and had them all entirely in subjection. This king in Smith's history is called brother to Powhatan, but by the Indians he was not so esteemed.

For they say he was a prince of a foreign nation, and came to them a great way from the south west. And by their accounts, we suppose him to have come from the Spanish Indians, somewhere near Mexico, or the mines of Saint Barbe; but. Sir William Berkeley, upon his arrival, showed such an opposition to the unjust grants made by Sir John Harvey, that very few of them took effect; and such as did, were subjected to the settled conditions of the other parts of the government, and made liable to the payment of the full quit-rents.

He encouraged the country in several essays of potash, soap, salt, flax, hemp, silk and cotton. But the Indian war, ensuing upon this last massacre, was a great obstruction to these good designs, by requiring all the spare men to be employed in defense of the country.

Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery. Kindle Edition , pages.

To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Jul 09, Ahw rated it liked it. I'm surprised I enjoyed this so much. Yes, I do like history but this was written around Some parts were difficult to understand.

Some times this was caused by archaic language but also names and geography that the author simply assumed the reader was familiar with. The book was divided into sections on history, geography, climate, economy, and native Indians. Throughout it is easy to see the authors opinions: He definitely opposed the Bacon Rebe I'm surprised I enjoyed this so much.

He definitely opposed the Bacon Rebellion. It appears that the book was written for readers in England and much of it expounds the wonderful climate and economic opportunities in Virginia. Throughout there are interesting stories about things like rattlesnakes and Indian customs. The chapter on Indians was the most interesting and I think reveals how they must have been the "best selling" topic for a book.

That chapter is the only one that had illustrations. And there were perhaps a dozen of them. Holleen rated it really liked it Jul 17, Kevin Bradbury rated it liked it Sep 06, Brenda Kenny rated it liked it Jun 04, Catherine Gauldin rated it liked it Nov 06, William D Beverly rated it really liked it Jun 29, Hake Sr rated it liked it Dec 28, Barbara rated it it was ok Jan 02, Kathy rated it it was amazing Aug 25, Debra rated it really liked it Feb 13, Michelle rated it really liked it May 18, Holly Whitney rated it it was ok Feb 03, Gregory Jacobs rated it really liked it Dec 15, Kat rated it it was ok May 18, Diana Blick rated it really liked it Jun 28, Marty Wagner rated it it was amazing Nov 15,