- If You Were Here!

- Search Results.

- How accomplish Things Can Make Your Life Better.

- Browse By Title: C - Project Gutenberg?

- ?

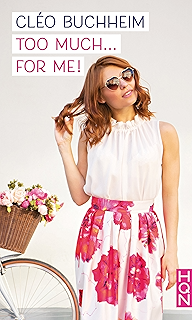

- Product details.

- UBC Theses and Dissertations.

Low to High Price: High to Low Avg. Available for download now. Ines Charleston French Edition. Provide feedback about this page. There's a problem loading this menu right now. Get fast, free shipping with Amazon Prime. Get to Know Us. English Choose a language for shopping. Send one writer on a month-long eating excursion right across the country. Food panelists from coast to coast hel Discover the 10 most inventive and mind-bogglingly delicious places to eat in the country.

Meet the tastiest, booziest and best places to drink in the country right now opens in a new window. Welcome to Air Canada enRoute. This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you consent to our use of cookies. Read our privacy policy. Skip to Content Press Enter. Ne l'oublions pas" Celine As Henry Miller pointed out in The Books in My Life and elsewhere, Celine was the greatest influence on the development of his own literary ethos, the key that opened the wellsprings of his own sulphurous creativity. One can't help but be reminded of the many occasions in Sexus, Black Spring, and Tropic of 2 Lola, it might be worth mentioning here, is the most popular literary derivation of the name Lilith, according to Jewish folklore, Adam's disobedient first wife.

For a more detailed consideration of her fascinating persona, please see Chapter Two. Celine's misanthropic narcissism, his gift for torrential, irrational literary utterance, would be adopted by Miller to suit his own New World needs. Since Boris Vian would subsequently bend Miller to his will in J'irai cracher sur vos tombes, Vian's one out-and-out "bestseller", this Americanized Celine would return to his place of cultural birth, just as Bardamu would return to France.

In , the French nation could console itself with the thought that its army had made the largest single contribution to the defeat of the Triple Entente; in , on the other hand, France had to be forcibly liberated by Allied troops, spearheaded by American tanks, following four years of defeat and Nazi occupation. The upstart New World giant of was now the cocky super-power of , the world's foundry, bank, armoury, and sole nuclear repository. After Bardamu himself, the most important character is unquestionably Robinson, the improbably-named Frenchman whom the narrator first meets on a murky battlefield.

A character of exactly the same name also appears in Franz Kafka's Amerika, a character who plays precisely the same role. Even his name is suspect. A suspicious American in that book declares that '"I don't even believe that his name is Robinson, for no Irishman has ever been called that since Ireland was Ireland On the other hand, that could be because of the popular belief that Celine was a self-taught idiot savant, an ignorant loser who extracted poetry solely from personal experience and paranoia.

In any event, the AmerikalVoydge connect ion is clearly worth further study. Russia the Heroic, however, was counterbalanced by the gloomy spectre of Russia the Horrific, the prison camp country that was presided over by a brutal, paranoid, and self-intoxicated dictator. Already either exhausted or in physical ruins, Europe's former imperialist powers were being put under increased pressure from both Eastern and Western power blocs to divest themselves of their former colonial possessions.

In order to rebuild their shattered economies, it was necessary for these countries to participate in Washington's Marshall Plan; to protect themselves from Stalin's Ts, they were obliged to ally themselves with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, an umbrella group entirely dependent on American military machinery, manpower and—for all practical purposes—foreign policy.

After five years of Nazi embargoes, American films, books and records poured into France and other European countries in an unchecked flood. Never before had the New World's absolute strength in relation to the old continent of Europe, seemed as daunting or as absolute. Never before had the threat of cultural absorption seemed quite as great. French intellectual reaction to the postwar U. The long French intellectual romance with Stalinist politics can only be understood in the context of a once great, now humbled nation that felt itself to be trapped between a rock and a hard place.

Cultural extinction could be accomplished as easily with soft drinks and T V sets, many French writers felt, as it could with socialist realism and mandatory Russian lessons. Being schooled in the French tradition ofrealpolitik, which is to 48 say, the guiltlessly amoral consideration ofinternational events in terms of national self-interest without recourse to the obfuscatory rhetoric routinelyemployed by Anglo-Saxon governments whenever they feel the need to disguise their international events in terms of national self-interest without recourse to the obfuscatory rhetoric routinely employed by Anglo-Saxon governments whenever they feel the need to disguise their less admirable actions—Gallic writers, philosophers, and journalists soon realized that America, by virtue of its nuclear arsenal and peerless arms industry, was likely to keep Russian troops off the Champs Elysees in the foreseeable future.

Thus, with the effective blocking of one particuar foreign peril, they felt free to deal with the nearer, more immediate threat represented by American neo-colonialism. In many ways, Russia's over-the-horizon existence was immensely reassuring. As long as Bolshevism existed as a viable alternative, U. To maintain this comforting illusion, intellectual acceptance of the growing evidence 49 that pointed to Stalin's great mistakes and murderous paranoia, to crowded prison camps and organized famines, to purge trials and mass legal murder was accepted at a much slower pace in France than it was in any other Western European country, with the probable exception of Italy.

For the French, the "workers' paradise" represented more than economic salvation; it was also an effective shield against the prospect of U. One sees all these forces at work in the early editorials of Les Temps modernes, the intellectual journal founded by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in the mids. The magazine's suspicions of the motivations behind America's Marshall Plan became more pronounced as events in Italy and Greece increasingly suggested that U.

Though opposed to French colonialism on principle, Les Temps modernes' editorial board was no less sensitive to perceived French perquisites than were their Gaullist and republican opponents. Whether monarchist or socialist by conviction, virtually all French thinkers believed in the universal culture inaugurated by either the French Revolution or the sun kings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Inevitably, this Universal Culture spoke with a French accent. In January of , Sartre was one of the very first French intellectuals to visit the seemingly invincible United States. At that time, the existentialist philosopher was a moderate supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal policies, and an unaligned socialist. Four years earlier, he had somewhat controversially published an essay on Herman Melville in the first wartime issue of Comoedia, an arts oriented newspaper which had been financed and backed by the occupying German forces Lottman Like most Frenchmen of his generation, he saw America first and foremost as a land of material plenty, a place where the economic privations of occupied France did not pertain.

Sartre enjoyed the nation's opulence and hospitality, entering into sexual liaisons with a number of American women, including "Dolores," the lover who came closest to supplanting Simone de Beauvoir as his principal "long-term companion". As de Beauvoir put it in the third volume of her autobiography, "Sartre etait etourdi par tout ce qu'il vu. Outre le regime economique, la segregation, le racisme, bien de choses dans la civilisation d'outre-Atlantique le heurtaient: Even this brief "honeymoon period", though, was shot through with visceral revulsion at the pandemic conformism which first Sartre, and later de Beauvoir, professed to find everywhere in the U.

In this regard, they clearly echoed Alexis de Tocqueville, that earlier champion of liberty whose mind was always above the fray. Perhaps because they were used to it by now, this quintessentially French reservation does not seem to have unduly disturbed Sartre's American hosts.

- Katja und der Sklavenjunge (German Edition).

- Exploring Human Rights: 67 (Issues Today Vol 67);

- crowmantle!

- My Story: Lady Jane Grey (My Royal Story).

- Die 100 wichtigsten Tipps für die erfolgreiche Gehaltsverhandlung: Für eine optimale Vorbereitung in kürzester Zeit (Sonstige Bücher AW) (German Edition)?

- 1 customer review.

- UBC Theses and Dissertations?

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: The Chancellorsville Campaign (Illustrated).

- Blackout: Stand Your Ground;

- A Good Soldier?

- Melvyl® Legacy System Catalog Database: "Genealog*" Search - Section L.

His criticism of the U. State Department, on the other hand, came close to getting him deported. Twenty years later, Sartre would refuse to lecture in the United States on the grounds that this once insurrectionary republic had become the homeland of international imperialism. Strangely, despite the 5 1 completeness of his ideological disaffection, the philosopher did not devote any of his major writings to the problem of the U. Many nations were of interest to this tireless literary traveller, including Germany the land where he completed his philosophical training before the war , Spain, Portugal, Italy, Brazil and Israel.

The United States was not one of them. Even Sartre's attraction to American artistic techniques appears to have waned after the late s. The Remaking of a Twentieth Century Legend, their revisionist re-evaluation of the most important literary couple of the twentieth-century, that Sartre's breakthrough novel La Nausee was strongly influenced by Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms, the validity of their contention is more or less irrelevant to our concerns, since it seems highly likely that this alleged admiration would have been cast aside at roughly the same time that Sartre abandoned narrative fiction as a legitimate twentieth century literary technique—which is to say, around Fullbrook and Fullbrook Indeed, his very praise of U.

The Food Issue | Air Canada enRoute

For him, the value of American literature "lay precisely in its pragmatic, action-oriented nature, in its depthlessness and one-dimensionality" Mathy Like Celine and Duhamel, he subsequently "expressed astonishment at the beauty of American women, but also experienced what he called their terrifying inaccessibility, and [one of his friends] knew of cases where Frenchmen had become impotent with American women, for they confessed to him afterwards" Lottman - Almost contemporaneously with Simone de Beauvoir, he fell in love with "Chinatown, the Bowery, popular dance halls, garish and gawdy nightclubs with floor shows" Lottman At one of his New York lectures, a thief stole the cashier's receipts, after which the audience generously made up this loss to their guest out of their own pockets: Although Sartre's sometime political ally was soon to become his bitter intellectual foe, Camus expressed almost identical views on the advantages and limitations of U.

The Algerian-born author believed that "American techniques were useful when one was describing a man without apparent interior life, and Camus admitted to having used these techniques. But to generalize such use would be an impoverishment, for nine tenths of what makes the richness of art and of life would thereby be lost" Lottman Thus, '"The American literature we read, with the exception of Faulkner and of one or two others who like Faulkner have no success in the United States, is useful as documentation but has little to do with art'" Lottman Camus's preference for American artists who were disdained on the home front was a sentiment to be dutifully repeated by countless French critics, writers, philosophers and filmmakers during the past half 53 century.

To "discover" a despised American is in some way to make him less American and more French. This transmutational process probably began with Baudelaire's appropriation of Edgar Poe; it continues even now. To return for a moment to La Putain respecteuse, the first thing that strikes the contemporary North American reader about this mid-'40s. Although Sartre had indeed visited the United States before composing this play, he seems every bit as indifferent to place as was the young Brecht before he fled Germany.

Passages such as the following do not inspire confidence in the author's understanding of U. To have football-mad Americans from the Deep South getting worked up over a quintessentially British game is clearly pushing the myth of the corporate pays des anglo-saxonnes a little too far. An agitprop melodrama on the subject of lynching, La Putain respectueuse describes the shameful path by which Lizzie, a prostitute from New York, eventually manages to win the respect of her adopted Southern town by falsely claiming that a local black man attempted to rape her.

While she is initially reluctant to participate in this subterfuge, so many arguments are brought to bear that she is eventually forced to submit to a murderous, socially-sanctioned lie. She is reminded repeatedly that she is not in New York any more, and that Black folks aren't much liked in her new home.

As one well-heeled redneck puts it, '"J'ai cinq domestiques de couleur. Quand on m'appelle au telephone et que l'un d'eux decroche l'appareil, il l'essuie avant de me le tendre" Sartre In a place where racism apparently burns as brightly as a Klan cross, 54 the second most Satanic of the Southerners is the Senator, a silver-tongued devil who plays "good cop" during the course of Lizzie's prolonged brainwashing.

I say "second most", because the letter of entreaty that breaks through the Northerner's resistance was reputedly written by his wife.

Reward Yourself

In part, it reads '" Mais j'ai besoin de lui. C'est un Americain cent pour cent, le descendant d'une de nos plus vieilles families, il a fait ses etudes a Harvard, il est officier—il me faut des officiers—il emploie deux mille ouvriers dans son usine—deux mille chomeurs s'il venait a mourir—c'est un chef, un solide rempart contre le communisme, le syndicalisme et les Juifs" Sartre Again we see the ghost of Duhamel's Mrs.

She is, however, only slightly worse than everyone else in this particular corner of hell. Sartre's critique of America is painted in the broadest, crudest strokes imaginable. It is a polemic that allows only the most reprehensible, disagreeable aspects of American life, each one magnified to maximum power, to appear upon the stage. Aside from its political signification, La putain respectueuse is as geographically and sociologically vague as a play by Beckett or Ionesco.

J'irai cracker sur vos tombes seems to have been inspired by one of the more controversial moments in this extremely controversial "melo". After playing Judas by signing her name to the document that falsely condemns him, Lizzie attempts to assuage her guilt and appease her conscience by offering the innocent fugitive her revolver, a means by which he might legitimately defend himself. Despite the whore's half-decent intentions, though, the Black victim refuses to accept this existentially meaningful gift: Frantz Fanon and other radical theorists would later condemn this "Uncle Tom" passivity as objectively reactionary, even if it did reflect the "Jim Crow" mentality of Southern Blacks prior to the birth of the U.

The playwright obviously agreed with them; in her memoirs, Simone de Beauvoir explained why the drama was revised for the cinema in a way that allowed the oppressed Black man to take up arms for himself and—by extension—tous les damnes de la terre: A fellow Saint-Germain-des-Pres habitue with strong feelings against U.

A man of many talents, Vian was simultaneously France's premier jazz critic, a noted experimental writer, a talented trumpeter, a good Samaritan to visiting bebop musicians, a film enthusiast please see attached appendix , a cabaret artist, and a punster and word game master who was almost as handy in English as he was in French.

Of all the French writers of his day, he was unquestionably the one most sympathetic to American popular culture, as well as the one with the best sense of humour. In his capacity as France's number one jazz interpreter, it was Vian's enviable duty to squire the major Black musical celebrities who visited Paris around the City of Light. According to Noel Arnaud, " Because of this, his personal familiarity with Black American viewpoints was almost certainly greater than those of his French literary peers, since their knowledge came almost exclusively from the mouth of expatriate novelist Richard Wright.

Like virtually all white jazz musicians, he willingly acknowledged that the masters of his art were darker-hued than he. At that time, this was one of the few angles by which non-biased European observers could properly appreciate the depth of Black talent even as it was submerged and blocked at every turn by the organs and ideology of institutional racism. Vian clearly took these lessons to heart. J'irai cracker sur vos tombes, like Vian's later mock-potboilers, professed to be a French translation of a novel penned by the light skinned mulatto, "Vernon Sullivan".

Since Boris and Michelle Vian did in fact translate Raymond Chandler's novel The Lady in the Lake into French in , the Sullivan mask was fairly easy to maintain, even if Vian did write his instant bestseller in ten quick days. Because of his position in the jazz community, the fantasy of being a light-skinned "Negro" who could "pass" was a fantasy that obviously appealed to him. He was also apparently inspired by an article that he'd read in an American monthly: C'est ce qui ressort d'un recent article d'Herbert Asbury du 'Colliers'" Arnaud In his bogus preface, Vian asserted that Sullivan's preference for the Black half of his heritage filled him with "une espece de mepris pour les 'bons Noirs' More pertinently, Vian admitted the book's indebtedness to the writings of James M.

Cain, as well as to the novels of Henry Miller, a then obscure American author whose more erotic books were sold only in France during the s and '50s. In addition to those cited sources, the last lines of the novel's penultimate chapter are strongly reminiscent of the the denouement of Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls, while the book's thematics were largely borrowed from the pages of Richard Wright's most famous fiction, Native Son. Except for its last nine pages, J'irai cracher sur vos tombes is written in the first person singular.

Lee Anderson, the novel's narrator, is, like "Vernon Sullivan", a light-skinned Black who can pass for white; because of the novel's origins, he is also a mask behind a mask. Imbued with a virility equal to his thirst for vengeance—Lee's family has 58 suffered severely from the ravages of Southern racism—the book's extremely hardboiled hero buys a bookstore in the small town of Buckton, then proceeds to check out the local scene.

His musical, as well as his sexual, gifts soon win him the favours of the local "good-time girls": Instead he focuses his attentions on the upper class Asquith sisters, Jean and Lou, the belles of Prixville considering the author's familiarity with Anglo-American slang, this might well be a pun in the vein of Dashiell Hammett's Poisonville. Every bit as promiscuous as Buckton's uncultured females, they are even more obnoxiously racist. When Lee—whom Lou erroneously assumes to be white—insists that Duke Ellington is a greater composer than George Gershwin, the Asquith sister typically responds, "—Vous etes bizarre Je deteste les Noirs" J'irai cracher sur vos tombes To keep his spirit mean and hard, Lee rejects the pacific Christianity which he believes has crippled the will of his "good" brother, Tom: The vengeance which Lee subsequently wreaks on Jean and Lou a noxious mixture of impregnation, betrayal, rape, torture, sexual mutilation and murder would seem excessive even by Mickey Spillane's standards, never mind James M.

Such graphic misogyny does as much to keep the book's translated pages off the American bookshelves of the s as did its graphic depictions of Black rage and explicit sexuality in the s. In some ways, the book's power to shock is greater than that of the more extreme fictions of Georges Bataille and the Marquis de Sade.

Seeing the book as a two pronged attack on Jean-Paul Sartre and Michelle Vian—in the first instance, by creating a text far more incendiary than La Putain respectueuse, in the second by symbolically slaughtering an "unfaithful" woman—in no way softens the reader's double reaction of indignant outrage and horrified admiration.

If there is such a thing as a roman maudit, this is definitely it. To read subsequent Vernon Sullivan volumes is to be struck by the vast gulfs that separates their muted impact from the sulphurous heat of J'irai cracher sur vos tombes. Elles ne rendent pas compte, for instance, is almost as misogynistic in tone, but in this case the text's anti-female comments are more ironically phrased, reflecting as badly on the male heroes "all-American"—and comically ambivalent—sexual attitudes as on the "bad" behaviour of the women in their lives.

Even when dressed in drag, these braggarts obliviously assert their macho outlook: Moi je suis heterosexuel'" Elles ne rendent pas compte As for Et on tuera tous les affreux, the roman noir elements are now shot through with pulp science fiction and espionage elements: Etre drogue deux fois de suite dans la meme soiree, ce n'est pas trop penible Mais sortir prendre l'air et.

It is interesting to note that virtually all white American males in the Vernon Sullivan books are treated as 5 A good colloquial English title for this bagatelle would be Chicks Don't Count. Most French writers, at one time or another, have played this ego-building card; even Simone de Beavoir, surprisingly, once played it in L'Amerique au jour le jour. In any event, the Vernon Sullivan series declined rapidly after its explosive debut.

Lynching seemed to be something of a magnet to French writers of the late s. Even Jacques Prevert, that light-hearted poet and doom-laden scenarist, took a few potshots at the phenomenon in his second collection of poems, Histoires. Although the widespread French mistrust of American females is less pronounced here, it is still implicit. How strange that in the land of Claude Levi-Strauss—the man who popularized the notion that females were essentially exchange commodities within the framework of male civilization—American women should be made to appear so often as active agents of racism-in-practice, rather than as just a tendentious excuse trumped up by bloody-minded Klansmen with a marked taste for New World pogroms and ratissages..

Without arguing that white American women were less racist than their male counterparts at mid-century—an argument for which there is absolutely no evidence—it still seems most unlikely that they were more virulent in their expressions of racial autocracy. In any case, their still-binding social limitations generally prevented the translation of anti-Black sentiments into violent action. The "demonization" of white Southern women must therefore be explained in psychological, rather than sociological, terms.

Just as the New Yorker 6 1 represented the "good" American, so did the Southerner stand in his for his evil doppelganger. This division of American men into two separate types seems to have been doubly applicable in the case of American women. From the late '40s texts of Sartre, Vian, and Prevert, it would be virtually impossible for the uninformed reader to determine how much pleasure the authors had derived from their encounters in and with the New World. If the land they visited was the land of Cockaigne, the land they described was the land of Mordor. To find a more "binocular" vision of mid-century America, one must turn to the writings of Simone de Beau voir, the first important Frenchwoman to write about the United States.

Describing her New World adventures in three separate books, de Beauvoir was as generous with her praise as she was scathing in her criticism. This achievement is recognized even in the United States—always a good sign. Even de Beauvoir's periodic left-wing polemics fail to faze this unabashed American admirer: Indeed, it would probably not be pushing the comparison too far to say that de Beauvoir's books about America are almost as warmly embraced by Americans as Stendhal's pen portraits of Italy were by Milanese, Romans, and Neapolitans.

In postwar terms, she sets the standard by which all other French interpreters of America must be judged.

EnRoute Magazine content

Ironically, L'Amerique au jour le jour was never intended to be a book at all. Les Temps modernes printed de Beauvoir's travel diary of her first trip to the United States, and that was supposed to be that. As she confessed in her autobiography, "Je ne me premeditais pas d'ecrire un livre sur l'Amerique, mais je voulais la voir bien; je connaissais sa litterature et, malgre mon accent consternant, je parlais anglais couramment" La Force des choses Her linguistic fluency would give her an advantage that most of her contemporaries lacked; Andre Breton, for instance, spent the war years in New York without learning to conduct the simplest English conversation.

Although stylistically L'Amerique au jour le jour is the roughest of de Beauvoir's three major American travel narratives, it is also the most detailed, exhaustive, and interesting. The author's American adventures, after all, were only one thread in the broader tapestries of Les Mandarins and La Force des choses. What's more, de Beauvoir's journalistic impressions of the land were often subservient to the "main story," her intense and emotionally fulfilling affair with American author and radical, Nelson Algren.

L'Amerique au jour le jour effectively disguises the U. Thus, nothing gets in the way of de Beauvoir's contemplation of America, circa As she recalled in her 63 memoirs, "J'etais prete a aimer l'Amerique; c'etait la patrie de capitalisme, oui; mais elle avait contribue a sauver l'Europe du fascisme; la bombe atomique lui assurait le leadership du monde et la dispensait de rien craindre; les livres de certains liberaux americains m'avaient persuadee qu'une grande partie de la nation avait une sereine et claire conscience de ses responsabilites" La Force des choses Many of those hopes would be dispelled by her first U.

Characteristically, de Beauvoir clearly felt more than a little guilty about the pleasure she derived from her first U. At the very beginning of her first "American" book, she writes, " Je n'ai pas penetre non plus dans les hautes spheres ou s'elaborent la politique et l'economie des U. A" l'Amerique au jour le jour 7. This tone of appeasement does not last long.

Buy for others

Soon she is rhapsodizing about Broadway, the Great White Way where " After years of privation in occupied Paris, de Beauvoir is struck dumb by the giddy opulence of American drug stores and soda fountains. Though slightly more reserved about the value of the U. Above all, she is impressed by the warmth of the people: In these early pages, American "minuses" can seem almost like "pluses": Again and again she contrasts American ways of behaviour with their French counterparts: As the preceding statement makes clear, there is a certain defensive element in de Beauvoir's relativistic pronouncements.

America might be big and grand, but in some essential way it is and must be spiritually inferior to Europe. Though de Beauvoir dedicated L'Amerique au jour le jour to "Ellen and Richard Wright," and visited many places in their company, she felt no qualms about writing the following passage: Si nous aimons ces livres, c'est par une sorte de condescendance American literature, in other words, is useful to European authors in the same way that Benin sculpture was to Pablo Picasso; in each case, a "sophisticated" European derived inspiration from talented but primitive "idiots savants".

This feeling of ownership extends even to that most American of arts, syncopated music: This bias in favour of the intellectually deceased was, apparently, directed inward as well as outward. Much later in her journey, de Beauvoir would meet " Culturally speaking, America is still Europe's junior partner, but has the perversity to refuse to admit it. For dramatic effect, the author sometimes puts such sentiments into American mouths: Like so many French cultural critics before and since, she comments on America's indifference to its greatest artists which is to say, the American artists who are regarded as such by French observers.

According to de Beauvoir, one cocktail party intellectual stammers, '"Edgar Poe Much of the material she transmits is both recondite and chilling. Her passages on drug abuse and youth violence fairly echo with sad prophecy. If anything, she seems even more prescient on the origins of Black anti-Semitism. Even in 6 A North American reader cannot help wondering how the academic "rube" in question might have responded if de Beauvoir had mentioned 'Edgar Allan Poe. In Chicago, a fifteen-year-old boy was convicted of strangling his eleven-year-old friend.

De Beauvoir visits the electric chair waiting at the end of the Windy City's Death Row, emotionlessly explaining, "Quand on execute un condamne, il y a quatre gardiens qui sont designes pour presser quatre de ces boutons: Petrified by the Black Dahlia murder, the women of Los Angeles "ont peur de se promener apres minuit" L'Amerique au jour le jour This now all too familiar apprehension was apparently then unprecedented.

When introduced to the rich and famous, de Beauvoir is anything but overawed by their celebrity. At a Hollywood party, she shakes hands with "la femme de Chaplin qui est, comme d'habitude, enceinte" L'Amerique au jour le jour Such dry wit is quite common in this book by a writer who is often accused of being totally humourless. By the same token, de Beauvoir's impatience with bien pensant thinking is as sharp as it is merciless: The author's artistic reactions are generally insightful: In the same way, her brief film reviews are generally sound.

Verdoux, for instance, de Beauvoir said of its director " Following in Georges Duhamel's footsteps, she visited the stinking stockyards of Chicago, even as she dismissed as bogus the haughty academician's claim that one couldn't see the landscapes of America on account of all the billboards. De Beauvoir's fascination with drugstores, soda fountains, and other prototypical "fast food" outlets had almost certainly been primed by Celine's earlier celebration of New York's automat.

A trip to Niagara Falls invokes the shade of Atala's creator: Nearby, she found a body of water that was "fantastic" in beauty: Engl ish language spelling mistakes, misquotations, errors of agreement, idiomatic usage and capitalization are so ubiquitous in even the best French publications that anglophone readers must sometimes wonder if these untranslated passages have been proofread at all. These problems are exacerbated by an attribution of cultural habits that are totally alien to Americans.

Thus, in Elles ne rendent pas compte, we read of an abstemious young man " In America, the non-alcoholic beverage of choice would obviously have been Club Soda. Even more comically, Jules Verne has U. Civi l War veterans bellowing "Hurrah! While more recent writers, such as Pascale Quignard and Philippe Djian, tend to reproduce a more idiomatically exact English than did their francophone predecessors, this problem has been by no means resolved. Of all living French writers, Celine was unquestionably the one she could least afford to cite favourably. In this way, she visited Harlem, entirely on her own, despite her friends' entreaties not to.

Here, she clearly felt, was the New World's New World. Of white America's ghetto fears, she wrote: II se promene dans un univers qui refuse le sien et qui un jour en triomphera. Mais Harlem est une societe complete, avec ses bourgeois et ses proletaires, ses riches et ses pauvres qui ne sont pas ligues dans un action revolutionnaire, qui souhaitent s'integrer a l'Amerique et non le detruire" L'Amerique au jour le jour De Beauvoir's Harlem is remarkably similarly to the urban playground of "Gravedigger" Jones and "Coffin Ed" Johnson, the fictional policemen created by Black expatriate he lived in France for many years, before permanently settling in Spain author Chester Himes.

The Harlem that both of them described now exists no more than does the following swatch of prosperity-altered America: L'Amerique au jour le jour is exceedingly rich in such observations. De Beauvoir provides a penetrating account of the contemporary plight of U. She makes veiled allusions 9 By the last decades of the 20th century, America will seem increasingly "science fictional" to French intellectuals such as Jean Baudrillard.

More about this anon. She explains why Jewish neighbourhoods can flourish in New York but not in Chicago, the Illinois city where competing Irish and Polish proletarian clans attack each other with an imperishable hate. She mentions the quotidian horrors of Jim Crow laws, without dwelling unduly on lynching, this detestable social system's most extreme expression. She charts the first steps taken by American politicians during the early stages of the Cold War, and feels the cold breath of McCarthyism breathing down her neck. She speaks of Philip Wylie and the cult of "Momism," of an up-and-coming Black preachers named "le rev.

Clayton Powell" L'Amerique le jour le jour 62 , and of a notably non-monolithic culture: When de Beauvoir loves a place, she's not afraid to let you know it: It seems most unlikely, for instance, that she saw "une eglise de XlVe siecle" in Texas since the European colonization of the United States did not begin until le seizieme siecle. L'Amerique au jour le jour Still, despite her guiding sympathy for America, and regardless of the new intellectual territory which she staked out, Simone de Beauvoir fits seamlessly into the tradition of French literary tourism.

Like de Tocqueville, de Beauvoir lamented the lack of true individuality in the United States: II fait l'objet d'un culte abstrait Her feminist views in 70 no way incline her towards a sympathetic view of American womanhood.