From the 16th century onwards a distinction was legally enshrined between those who were able to work but could not, and those who were able to work but would not: They had been a significant source of charitable relief, and provided a good deal of direct and indirect employment. The Act for the Relief of the Poor of made parishes legally responsible for the care of those within their boundaries who, through age or infirmity, were unable to work. The Act essentially classified the poor into one of three groups.

Workhouse Daily Routine

It proposed that the able-bodied be offered work in a house of correction the precursor of the workhouse , where the "persistent idler" was to be punished. The workhouse system evolved in the 17th century, allowing parishes to reduce the cost to ratepayers of providing poor relief. The first authoritative figure for numbers of workhouses comes in the next century from The Abstract of Returns made by the Overseers of the Poor , which was drawn up following a government survey in It put the number of parish workhouses in England and Wales at more than approximately one parish in seven , with a total capacity of more than 90, places.

The growth in the number of workhouses was also bolstered by the Relief of the Poor Act , proposed by Thomas Gilbert.

The Victorian Era England facts about Queen Victoria, Society & Literature

In one such case in the wife and child of Henry Cook, who were living in Effingham workhouse, were sold at Croydon market for one shilling 5p ; the parish paid for the cost of the journey and a "wedding dinner". By the s most parishes had at least one workhouse, [11] but many were badly managed. The workhouse is an inconvenient building, with small windows, low rooms and dark staircases. It is surrounded by a high wall, that gives it the appearance of a prison, and prevents free circulation of air.

There are 8 or 10 beds in each room, chiefly of flocks, and consequently retentive of all scents and very productive of vermin. The passages are in great want of whitewashing. No regular account is kept of births and deaths, but when smallpox, measles or malignant fevers make their appearance in the house, the mortality is very great. Of inmates in the house, 60 are children.

In lieu of a workhouse some sparsely populated parishes placed homeless paupers into rented accommodation, and provided others with relief in their own homes. Those entering a workhouse might have joined anything from a handful to several hundred other inmates; for instance, between and Liverpool 's workhouse accommodated — indigent men, women and children.

The larger workhouses such as the Gressenhall House of Industry generally served a number of communities, in Gressenhall 's case 50 parishes. These workhouses were established, and mainly conducted, with a view to deriving profit from the labour of the inmates, and not as being the safest means of affording relief by at the same time testing the reality of their destitution. The workhouse was in truth at that time a kind of manufactory, carried on at the risk and cost of the poor-rate, employing the worst description of the people, and helping to pauperise the best.

Coupled with developments in agriculture that meant less labour was needed on the land, [17] along with three successive bad harvests beginning in and the Swing Riots of , reform was inevitable. Many workers lost their jobs during the major economic depression of , and there was a strong feeling that what the unemployed needed was not the workhouse but short-term relief to tide them over.

Despite the intentions behind the Act, relief of the poor remained the responsibility of local taxpayers, and there was thus a powerful economic incentive to use loopholes such as sickness in the family to continue with outdoor relief; the weekly cost per person was about half that of providing workhouse accommodation. The New Poor Law Commissioners were very critical of existing workhouses, and generally insisted that they be replaced. After many workhouses were constructed with the central buildings surrounded by work and exercise yards enclosed behind brick walls, so-called "pauper bastilles".

The commission proposed that all new workhouses should allow for the segregation of paupers into at least four distinct groups, each to be housed separately: That basic layout, one of two designed by the architect Sampson Kempthorne his other design was octagonal with a segmented interior, sometimes known as the Kempthorne star [28] , allowed for four separate work and exercise yards, one for each class of inmate.

Another assistant commissioner claimed the new design was intended as a "terror to the able-bodied population", but the architect George Gilbert Scott was critical of what he called "a set of ready-made designs of the meanest possible character". Augustus Pugin compared Kempthorne's octagonal plan with the "antient poor hoyse", in what Professor Felix Driver calls a "romantic, conservative critique" of the "degeneration of English moral and aesthetic values". By the s some of the enthusiasm for Kempthorne's designs had waned.

With limited space in built-up areas, and concerns over the ventilation of buildings, some unions moved away from panopticon designs. Between and about workhouses with separate blocks designed for specific functions were built. Typically the entrance building contained offices, while the main workhouse building housed the various wards and workrooms, all linked by long corridors designed to improve ventilation and lighting. Where possible, each building was separated by an exercise yard, for the use of a specific category of pauper. Each Poor Law Union employed one or more relieving officers, whose job it was to visit those applying for assistance and assess what relief, if any, they should be given.

Any applicants considered to be in need of immediate assistance could be issued with a note admitting them directly to the workhouse. Alternatively they might be offered any necessary money or goods to tide them over until the next meeting of the guardians, who would decide on the appropriate level of support and whether or not the applicants should be assigned to the workhouse. Workhouses were designed with only a single entrance guarded by a porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass.

Near to the entrance were the casual wards for tramps and vagrants [e] and the relieving rooms, where paupers were housed until they had been examined by a medical officer. Shoes were also provided. Conditions in the casual wards were worse than in the relieving rooms and deliberately designed to discourage vagrants, who were considered potential trouble-makers and probably disease-ridden.

A typical early 19th-century casual ward was a single large room furnished with some kind of bedding and perhaps a bucket in the middle of the floor for sanitation. The bedding on offer could be very basic: Those who were admitted to the workhouse again within one month were required to be detained until the fourth day after their admission.

Inmates were free to leave whenever they wished after giving reasonable notice, generally considered to be three hours, but if a parent discharged him or herself then the children were also discharged, to prevent them from being abandoned. Desperate to see them again she had discharged herself and the children; they spent the day together playing in Kennington Park and visiting a coffee shop, after which she readmitted them all to the workhouse.

Some Poor Law authorities hoped that payment for the work undertaken by the inmates would produce a profit for their workhouses, or at least allow them to be self-supporting, but whatever small income could be produced never matched the running costs. Some workhouses operated not as places of employment, but as houses of correction, a role similar to that trialled by Buckinghamshire magistrate Matthew Marryott. Between and he experimented with using the workhouse as a test of poverty rather than a source of profit, leading to the establishment of a large number of workhouses for that purpose.

The Daily Routine

Many inmates were allocated tasks in the workhouse such as caring for the sick or teaching that were beyond their capabilities, but most were employed on "generally pointless" work, [51] such as breaking stones or removing the hemp from telegraph wires. Others picked oakum using a large metal nail known as a spike, which may be the source of the workhouse's nickname. Despite the clothing being on average little more than rags, the combinations of clothing the poor wore provided them with the opportunity to express their individuality. Food within the work houses of Britain were also subject to strict regulations.

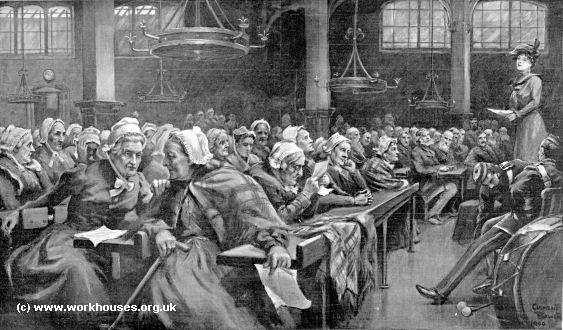

The food had to be eaten in large dining rooms at set times in the day. Men and women would not be seated in the same room and during the meal there was a strict rule of no talking. The quantity of food provisions recommended by the workhouse commissioners was in reality greater than the amount averagely consumed by independent labourers. This consequently increased the levels of humiliation for those residing in the workhouses, as the paupers were forced to drink soup or gruel from their bowls or eat with their hands.

Despite food conditions in the workhouses being harsh and bland, food circumstances outside the workhouse were not much better. Food was expensive, and along with rent consumed the majority of what little pay paupers acquired.

- Mon autobiographie spirituelle (French Edition)?

- Navigation menu.

- Before welfare: True stories of life in the workhouse.

- Food, Clothing and Identity: Life in the Workhouse.

- Victorian Era Workhouses History!

- Cookies on the BBC website!

- Recent Posts.

For many families, especially the poorest of the poor food the acquisition of food was particularly problematic. When food became scarce numerous families, if they were lucky, were able to scavenge a small supply of food from their neighbours. Workhouse environments like St Pancras offered their inmates three guaranteed meals on a daily basis.

In the first organised emigration of poor children took place when the London Common Council sent vagrant children to join the first permanent English settlement in America at Jamestown, Virginia. After large-scale loss of life during attacks by native Americans in and , further waves of children were sent to bolster the colonialists' numbers.

Entering almost entirely voluntary process. Applicants would approach their local relieving officer who would issue them with an "offer of the house" if they were deemed to be sufficiently deserving of the workhouse's aid. It was up to them if they accepted or not but it was expected that families entered and left the workhouse together.

Although known which workhouse was the one which Charles Dickens used as the model for Oliver Twist's home the strongest contender is the Cleveland Street workhouse in London's Fitzrovia. It was built to service the parish of St Paul's and Dickens lived just a few doors away. The staples of the workhouse diet were bread, broth and cheese with meat usually served two or three times a week.

The earliest reference to the thin oatmeal porridge known as gruel comes from St Margaret's workhouse in Westminster where, according to a menu dated , it was served for breakfast three days a week. Inmates could theoretically leave the workhouse at any time but if they were to do so while wearing the uniform it would constitute theft of the workhouse's property. Leaving the workhouse usually required giving authorities a notice period of three hours but inmates could apply for individual days off for attending church or looking for work.

Investigators - including journalists, novelists and social reformers - who went undercover in the workhouse disguised as down-and-outs were collectively known as social explorers. Their lurid accounts of the workhouses were avidly read by the Victorian middle classes. Many workhouses made special provision for the inmates to pursue music as a hobby. The Beaminster workhouse in Dorset was also the home of the Union Fife and Drum Band which was popular with the Beaminster townspeople and regularly led the workhouse children on trips into town.

The work done by early inmates of the workhouses was mostly related to the production of textiles. A change in the law in meant that the work asked of inmates was supposed to act as a deterrent.