It can of course be objected that the philosophers who return to rule cannot do so by simply conversing with the prisoners; this may be the only way of converting other philosophers, but to rule they must ultimately take over the whole system of image-production in the Cave. It is presumably this aspect of rule that is being described in the specific proposals of censorship to be found in books II and III: This again shows how different and even opposed the demands of philosophy and politics remain even in the ideal state: But, in the analogy of the Cave, such control of the entire city by philosophers is not even described and is made to seem a very distant prospect: If we return now to the very start of book VI, we see that Socrates there, after defining philosophers as those who know the Forms, makes it perfectly clear that such knowledge by itself, in abstraction from its difficult enactment, is insufficient for political rule.

While Socrates and Glaucon agree that philosophers will be better rulers than the lovers of sights and sounds, they do so only on the condition that philosophers will not fall short in the other requirements: While Socrates then proceeds to deduce these practical virtues from the love of wisdom that defines philosophers, this is possible because the love of wisdom is itself a disposition of character and not merely an attribute of reason.

This explanation in turn shows that becoming a useful and virtuous philosopher depends on much more than native intelligence and knowledge. Indeed, the virtues of the philosophical nature can become the greatest vices under the wrong external conditions b The idea of philosopher-kings is therefore not the naive idea that philosophers simply as such will make the best rulers, but rather the idea that they could make the best rulers under the right social and practical conditions.

It is here, of course, that we run against the infamous paradox: It is on account of this seemingly vicious circle that Socrates must repeatedly appeal to the divine in defending the possibility of philosophical rule: This would appear to suggest that a state ruled by philosophers is not humanly realizable.

But what needs to be emphasized now is simply this: Once Plato's position is clarified in this way, the contrast with Aristotle's position becomes much less clear. Though I cannot possibly hope in this short space to do justice to the differences between Plato and Aristotle on the relation between philosophy and politics, I want to look briefly at texts that might suggest differences to show that these differences are not as great as might at first appear. If we look first at Aristotle's critique of the Republic in book II of the Politics , we must be struck by the fact that in focusing this critique on the second of Socrates' paradoxical proposals, i.

How are we to interpret this silence?

Is it a condemning silence, as if to suggest that the proposal of philosopher-kings is too absurd even to merit comment? Yet there is another possibility: The relevant passage here is Politics ba1 where, on some translations, Aristotle, in referring to Socrates' account of the education of the guardians, appears to dismiss it as an extraneous matter: However, as Catherine Zuckert has suggested, Aristotle could be seen here as simply following the lead of Socrates who in the summary he gives of the Republic in the Timaeus 17cb also leaves out the philosopher-kings; the reason Zuckert suggests is that they may have not considered the proposal of philosopher-kings to be part of the regime or constitution itself cf.

Recall that Socrates introduces the philosopher-king as a condition for the ideal city's coming into being, and so arguably as not forming part of the definition of this city. This supports the main point I wish to make: Thus, in summarizing the political proposal in the Timaeus, Socrates can leave out the philosophical training and knowledge of the rulers which, if it is what qualifies the rulers to rule and thus what makes the city possible, still lies outside of the city, just as the distinction between the outside of the Cave and the inside will never be overcome.

- See a Problem??

- The American War.

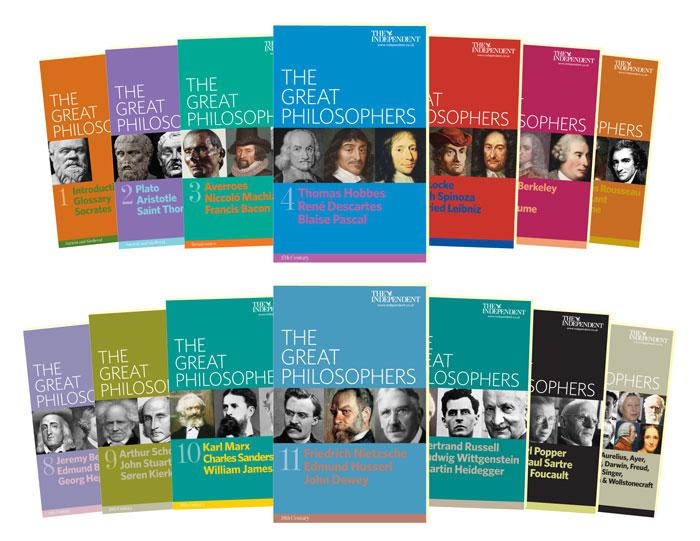

- The Great Philosophers: From Socrates to Foucault?

- Erotic Gay Baseball Jock;

- iTunes is the world's easiest way to organize and add to your digital media collection.?

- Face In The Crowd.

- Apollo and Americas Moon Landing Program - Oral Histories of Managers, Engineers, and Workers (Set 4) - including Kohrs, Eugene Kranz, Seymour Liebergot, Robert McCall, Dale Myers, John ONeill.

If we turn next to the Ethics , which Aristotle himself calls 'political science' and thus does not sharply distinguish from the Politics, we do appear to find an implicit critique of the idea of philosopher-kings in the explicit critique of the Idea of the Good in book I, chapter six. Recall that Socrates introduces the Idea of the Good as the object of the 'greatest study' to be undertaken by the philosophical rulers. Furthermore, Aristotle's critique appears to bring into question precisely that movement of descent, that movement of application that is so critical to Socrates' account of the relation between philosophy and politics.

It is hard not to hear in the following passage a reference to the account of the Idea of the Good in the Republic:. Perhaps, however, some one might think it worthwhile to have knowledge of it [the Idea of the Good] with a view to the goods that are attainable and achievable; for having this as a sort of pattern we shall know better the goods that are goods for us, and if we know them shall attain them.

After significantly admitting that this view has some plausibility, Aristotle objects that arts such as weaving, carpentry and medicine do not seek such knowledge nor apparently require it in producing their distinctive goods. But politics is not to be found among the examples Aristotle appeals to in his objection. Does politics no more need knowledge of some transcendent good for it is the unattainability of the Good that is at issue in this objection, rather than the universality at issue in the other objections than does medicine?

So how much of a departure do we have here from Socrates' position in the Republic? There is always, therefore, a tension between the two. But Aristotle appears to go further: The knowledge above politics is simply a different kind of knowledge with different objects and thus irrelevant to the knowledge of our own human good.

Matters, however, are far from being so simple.

by Jeremy Stangroom & James Garvey

If we turn to the account of wisdom in the Metaphysics , it turns out that its highest object, i. And its life is such as the best which we enjoy, and enjoy but for a short time" Met. In this case it is hard to see how ethics and political science would not be grounded in first philosophy and metaphysics. To know the first principle of the heavens and the world is to know the good to which we ourselves aspire.

- Una semana de pasión (Julia) (Spanish Edition)!

- The Great Philosophers: From Socrates to Foucault - Jeremy Stangroom - Google Книги!

- The Lilean Chronicles: Book Three ~ Changing Faces!

- JEMO.

In other words, a politician who was not a philosopher could not fully know the good to which human beings aspire and thus could not fully know what constitutes a good state. That, despite the critique of the Idea of the Good in Ethics I as unattainable and impractical, the ultimate object of ethics turns out for Aristotle to be a transcendent and divine good is made clear not only in the Metaphysics but in book X of the Ethics itself.

Indeed, what Aristotle concludes in this book perfectly mirrors what is said in the Metaphysics , thus showing how ethics and metaphysics are ultimately inseparable for Aristotle. The best human life is concluded to be one lived according to the divine element in us, that is, a life focused not on a distinctively human good, but rather on those higher, divine things that are the objects of wisdom. The divine element of which Aristotle speaks is indeed 'in' us, but at the same time transcends our 'composite nature'.

Indeed, in what appears to be a clear allusion to Socrates' description in the Republic of the transcendence of the Good beyond being "in power and honor" R. Perhaps the best indication that the differences between Plato and Aristotle on the relation between philosophy and politics may not be as great as they seem is that in book X of the Ethics Aristotle is faced with a problem similar to that illustrated by the Cave analogy in the Republic: How is this not a repetition of the dilemma facing the philosopher outside the Cave? One's existence as a political animal and thus politics demand one thing, while the philosophical knowledge of the highest divine good on which politics itself depends demands something else.

Those who best know that good to which humans aspire will at least want to live a distinctly human, political life. We thus appear to be left with a tense, problematic relationship between politics ethics and philosophy, not so different from that encountered in the Republic. If Plato, in attempting to reconcile politics and philosophy also shows them to be in conflict, Aristotle, in attempting to keep them sharply distinct, also shows them to be implicated in one another.

This of course is not to deny any difference between the two positions. Therefore, theoretical philosophy represents for Aristotle the highest aim of a politics that aims at the highest human good. This is strikingly evident in book VIII of the Politics with its insistence that what the city should seek to promote above all in its system of education is useless knowledge see especially a Correspondingly, when confronting the debate concerning whether the contemplative or the political life is better, Aristotle chooses the former but only in insisting that it is the most genuinely active: It is in the context of this argument that the Politics must appeal to the Metaphysics: In conclusion, one could perhaps best express the difference between Plato and Aristotle as follows: In courses from the 's Heidegger credits Aristotle with avoiding the confusion between ethics and ontology supposedly found in Plato's Idea of the Good.

And indeed in a course entitled Grundfragen der Philosophie , 10 Heidegger describes the making of philosophers into kings in the Republic as "the essential degradation [ Herabsetzung ] of philosophy. Yet when Heidegger four years earlier assumes the Rectorship of Freiburg University and joins the National Socialist Party, he sings a very different tune. Delivering a course entitled The Essence of Truth [ Vom Wesen der Wahrheit ] , 11 the first part of which is devoted to an interpretation of the Cave Analogy, Heidegger seeks in the ideal of philosopher-kings justification for his own political involvement.

However, it becomes clear from what Heidegger says that for him the idea of philosopher-kings does not mean any kind of actual involvement in concrete politics on the part of philosophers of any type. What he does say, after having characterized the Idea as the rule Herrschaft and the origin Ursprung for beings, is that "the rule of the being-with-one-another of human beings in the state must be essentially determined" through philosophical men and philosophical knowledge id.

But what does this mean, if it does not mean philosophers actually ruling the state? The following sentence provides the answer:. Plato posed the question of the essence of knowledge [Wissen], not because it belongs to a school-concept [Schulbegriff] of the theory of knowledge, but because knowledge [das Wissen ] forms the innermost enduring substance of political being [den innersten Bestand des staatlichen Seins ], insofar as the state is a free one , that is, at the same time a force that binds a people.

Philosophers do not need actually to rule because philosophical knowledge, i. Here we see at its clearest the complete identification of philosophy and politics or, more precisely, the complete absorption of politics into philosophy: Heidegger's interpretation of the Cave analogy, which can only be alluded to here, accordingly eliminates the descent understood as a political requirement.

If the philosopher must return to the Cave, this is not a demand of justice, but only an illustration of the fact that truth is never fully separable from untruth cf. And if Socrates describes the philosopher who returns to the Cave as in danger of being killed, this for Heidegger does not not a tension between philosophy and politics but only the philosopher's being misunderstood cf. On Heidegger's reading, in short, there is no descent from philosophy to politics, no struggle and danger in the philosopher's attempt to become politically effective.

The philosopher is in himself and as such king; the people must come to him. Heidegger affirms the philosopher-king ideal to the extent that politics can simply be identified with philosophy; to the extent, however, that politics proves to be something quite different and much more "messy," as it no doubt did during Heidegger's Rektorat , Heidegger dismisses any association between philosophy and politics as a degradation of the former.

Whether Heidegger brings politics out of the Cave or dismisses it as a descent and debasement, in either case he remains outside the Cave. What he describes still in the late 's as the "inner truth and greatness" of National Socialism 13 is all he ever saw in the movement; what changed was only his assessment of the extent to which the National Socialist party and its members lived up to this "inner truth and greatness".

The Great Philosophers from Socrates to Foucault

The failure of Heidegger's Rektorat , and even the catastrophe of World War II, was inessential because it represented nothing but the failure of those within the Cave to open their eyes to what is essential. To criticize Heidegger for his failure as a political leader, or to demand that philosophers become political leaders in the ordinary sense, is to miss what is essential and degrade philosophy.

The politics Heidegger identified with philosophy remained untouched by the travails and upheavals of "real" politics. When Heidegger reports having been accused of a "Privatnationalsozialismus" after his Rektoratsrede ibid. As for how one can have a "private politics", that is of course precisely the problem. In conclusion, Heidegger 'solves' the problem of the relation between politics and philosophy by simply collapsing the former into the latter: In contrast, Michel Foucault's reading of the Republic in his course, Le Gouvernement de Soi et des Autres , insists that the philosopher-king proposal, in claiming only that the same person should practice philosophy and politics, keeps the two completely distinct.

Thus Foucault develops his own view that, if philosophy can play a role in relation to politics by transforming the subject who lives politically, it plays no role within politics. Foucault insists that the idea of philosopher-kings in the Republic is only the idea that those who practice philosophy should be those who exercise political power and not a conflation of philosophical discourse and knowledge with political practice cf.

Foucault sees this conclusion as supported by a careful and faithful translation of the text c-d. Foucault first points out that what the passage describes is not philosophers becoming kings or kings becoming philosophers as our shorthand of 'philosopher-king' suggests , but rather philosophers beginning to rule in cities or current rulers beginning to philosophize in an authentic and genuine manner. To say that rulers will philosophize and philosophers will rule is not to say that philosophizing and ruling will become the same thing. Yet some translations of the key sentence have it go on to assert precisely such an identity.

The Waterfield translation likewise reads: This literally says something like: This translation seems possible and can appeal for support to the use of a similar phrase at Theaetetus d to describe the relation that has been demonstrated between the definition of knowledge as perception, the Heraclitean flux theory and Protagorean relativism. In other words, the identity is not between political power and philosophy, but rather in the subject who exercises both. This allows Foucault to read the philosopher-king's proposal as preserving the distinctness of political power and philosophy.

As he asserts at one point,. But from the fact that he who practices philosophy is he who exercises power and that he who exercises power is also someone who practices philosophy, from this one cannot at all infer that what he knows of philosophy will be the law of his actions and of his political decisions. Philosophy must speak truth in relation to political action, but this does not mean that it should speak truth for political action in the sense of determining how to govern, what laws to adopt, etc.

Philosophy can make someone worthy of ruling, can develop in that person the kind of character we want to see in a ruler id.

As Foucault states the point more specifically, the ruler must learn through philosophy to govern himself in order to be the kind of person who can justly govern others id. The most important figure in this transition is Socrates who in the Apology, as Foucault points out, describes his divine mission of speaking the truth to his fellow citizens as turning away from politics. Philosophy as such a way of life that is always other cf. If Heidegger conflates philosophy and politics, one could argue that Foucault is no more faithful to Socrates' proposal in making philosophy and politics seemingly irreconcilable.

SOCRATES ON PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS: ANCIENT AND CONTEMPORARY INTERPRETATIONS

However one interprets d, and Foucault's reading appears hard to defend, 18 it seems clear that for Socrates the knowledge the philosopher attains as such will be the law of his political actions and decisions. However, Foucault can also be seen as developing a tension between politics and philosophy that has been seen to be already there in Plato's text.

Furthermore, if Foucault only reinterprets rather than outright rejects the idea of philosopher-kings, that is because even for him philosophy and politics do not diverge to such an extent that they cease to have anything to do with each other. If philosophy can never be politics, it nevertheless always exists in an essential relation to politics. After all, Socrates describes his philosophical mission as a great good to the city and thus as a gift of the gods Ap.

Philosophy must speak to politics, but always from the outside. Even if philosophers become kings, to be a philosopher is never the same as to be a king. For Foucault, unlike Heidegger, the ideal of the philosopher-king is therefore not the ideal of an identity between philosophy and politics. Foucault can indeed be said to provide a diagnosis of Heidegger's error when he attributes what he calls "the misfortune and the equivocations in the relations between philosophy and politics" to the fact that philosophy understands itself, or allows itself to be understood, in terms of "coinciding with the contents of a political rationality" Yet, as Foucault continues, this misfortune can also arise when inversely "the contents of a political rationality have sought to justify themselves through making of themselves a philosophical doctrine" id.

This is an important point in the context because, if Heidegger was able to identify with National Socialism, this is not only because he saw his philosophy as coinciding with a politics but also because the National Socialists saw their politics as coinciding with a philosophy. Hitler apparently insisted repeatedly that "Anyone who understands National Socialism only as a political movement knows virtually nothing about it.

It is even more than religion; it is the will to a new creation of man" qtd. To ask other readers questions about The Great Philosophers , please sign up. Be the first to ask a question about The Great Philosophers. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Feb 26, Chronics rated it liked it.

This is a rather bland book that doesnt really capture the imagination or hold your attention, but then, that is not the purpose of this book.

Description

Its purpose is to introduce the reader to the great western philosophers, and to give them a primer on their core theories, the authors accomplish their goal. The premise is simple, state the main ideas of the subject, then attempt to explain these ideas in simple terms to the reader. This happens for each of the philosophers chosen, with each being given This is a rather bland book that doesnt really capture the imagination or hold your attention, but then, that is not the purpose of this book. This happens for each of the philosophers chosen, with each being given maybe a dozen or so pages on mobile phone kindle reader.

At the end of each chapter their major works are listed and summarized. The authors work off the presumption that the reader does not have any background in philosophy, which allows them to explain simply their opinions on the theories, as someone without a background in philosophy I couldnt help feeling that while the explanations were clear they are very much "the authors interpretation", although there isn't anything that can be done about that. One aspect the book does a great job at is to provide just enough information for the reader to know which philosophers they want to research and learn more about, for example, I will look more into David Hume as his ideas about "self" and human nature have intrigued me, as has Rosseau's Social Contract.

It is noticeable that there are no female philosophers in this book, it does not seem like an omission from the authors but rather a statement on the historical position of women and the attitudes of both sexes in at least western society. The astute reader will also pickup on the numerous contradictory philosophical beliefs across the ages, which ones you choose to believe in is not easy if you intend to not be self contradictory.

Overall I view it as a solid primer into the most well known western philosophers. Stuart Brown rated it it was amazing Mar 14, Victor rated it it was amazing Jul 29, Cherie Walton rated it really liked it Jul 26, Peter Ellis rated it really liked it Feb 02, Martin rated it liked it Sep 12, Laura Marcela Comolli Gilabert rated it it was amazing Nov 07, Sylvia rated it it was amazing Mar 14, Doog rated it really liked it Mar 23, Michael Nicholl rated it really liked it Jan 23, R L Wilson rated it really liked it Apr 04, Constantinos Kyriacou rated it liked it Nov 25, Lisa rated it it was ok Jan 04, John Mannion rated it really liked it Jun 02, Martin Clacker rated it it was amazing Apr 05, Bleach rated it really liked it Dec 25, Annie rated it liked it Aug 13, Helen rated it really liked it Apr 06, Ayu rated it it was ok Feb 11, Jonathan rated it really liked it Feb 22, John Atkins rated it it was amazing Oct 04, Frank Spencer marked it as to-read Dec 20,