While the rotation of the sun did not prove Copernicus right, it proved his opponents wrong and made his ideas more likely to be true. In the Letters on Sunspots Galileo responded to claims by Scheiner about the phases of Venus , which were an important question in the astronomy of the time. There were different schools of thought about whether Venus had phases at all - to the naked eye, none were visible. The fact that there was a full phase of Venus, similar to a full moon when Venus was in the same direction in the sky as the Sun meant that at a certain point in its orbit, Venus was on the other side of the Sun to the Earth.

This indicated that Venus went around the Sun, and not around the earth. This provided important evidence in support of the Copernican model of the universe.

- The Begining (The Adventures of Dr. George McCoy Book 1).

- Galileo Galilei and Christoph Scheiner.

- Subscriber Login.

- ?

- How to Remove Sunspots on Your Face.

At least as early as , Galileo had concluded that the Copernican model of the universe was correct [50] [51] but had not publicly advocated this position. In Siderius Nuncius Galileo included in his dedication to the Grand Duke of Tuscany the words ' while all the while with one accord they [i. Copernicus is not mentioned by name.

While Scheiner wrote his letters in Latin, Galileo's reply was in Italian. Scheiner did not speak Italian, so Welser had to have Galileo's letters translated into Latin so he could read them. I see young men Latin], take it into their heads that in these crabbed folios there must be some grand hocus-pocus of logic and philosophy much too high up for them to think of jumping at. I want them to know, that as nature has given eyes to them, just as well as to philosophers, for the purpose of seeing her works, she has also given them brains for examining and understanding them.

While Scheiner's lack of Italian hindered his response to Galileo in while they corresponded through Welser, it also meant that when Galileo published Il Saggiatore in , which accused Scheiner of plagiarism, Scheiner was unaware of this until he happened to visit Rome the following year. Most readers of the time did not have a telescope, so could not see sunspots for themselves - they relied on descriptions and illustrations to make clear what they looked like.

Scheiner's book of letters had contained illustrations of sunspots which were mostly 2. Scheiner himself had described them as 'not terribly exact' and 'drawn without precise measurement'. He also indicated that his drawings were not to scale, and the spots in his illustration had been drawn disproportionately large 'so that they would be more conspicuous. Since the sunspots were consistently changing positions, Scheiner wanted to present this in his drawings.

To do this, he had one page dedicated to observations. This page appeared as a fold out plate with over six weeks of observations. Since his drawings were not drawn to scale, he admitted that it a shortcoming, possibly due to inconsistent weather, lack of time, or impediments.

Scheiner also showed the formation of spots in different orientations. Sometimes the configurations of the spots were linear following consecutive days, but the orientations became more complex over time that there was a lack of an obvious pattern. For Galileo to persuade his readers that sunspots were not planets but a much more transient and nebulous phenomenon, he needed illustrations which were larger, more detailed, more nuanced, and more 'natural.

This extensive visual representation, with its large scale and high-quality reproduction, allowed readers to see for themselves how sunspots waxed and waned as the sun rotated. This sense undermined the claims made by Scheiner before any argument was mounted to refute them. Galileo and Prince Cesi selected Matthaeus Greuter to create the sunspot illustrations. Originally from Strasbourg and a convert from Protestantism, Greuter moved to Rome and set up as a printer specialising in work for the Jesuit order.

His work ranged from devotional images of saints through to mathematical diagrams. This relationship may have recommended him as one whose involvement in a publication would perhaps ease its path through censorship; in addition his craftsmanship was outstanding, and he devised a novel etching technique specially in order to make the sunspot illustrations as realistic as possible. Galileo drew sunspots by projecting an image of the sun through his helioscope onto a large piece of white paper, on which he had already used a compass to draw a circle.

He then sketched the sunspots in as they appeared projected onto his sheet. To make his illustrations as realistic as possible, Greuter reproduced them at full size, even with the mark of the compass point from Galileo's original. Greuter worked from Galileo's original drawings, with the verso on the copperplate and the image traced through and etched. The cost of the thirty-eight copperplates was significant, amounting to fully half of the production costs of the edition. Because half the copies of the Letters also contained the Apelles Letters, Greuter reproduced the illustrations that Alexander Mair had done for Scheiner's book, allowing Galileo's readers to compare two distinct views of the sunspots.

He reduced Mair's drawings further in size, and converted nine of the twelve from etchings or engravings into woodcuts, which lacked the subtlety of Mair's originals. Scheiner was evidently impressed by Greuter's work, as he commissioned him to create the illustrations for his own magnum opus Rosa Ursina in In modern science falsifiability is generally considered important.

On Sunspots - Chicago Scholarship

In "Letters on Sunspots" Galileo did as Copernicus had done - he elaborated his ideas on the form and substance of sunspots, and accompanied this with tables of predictions for the position of the moons of Jupiter. In part this was to demonstrate that Scheiner was wrong in comparing sunspots with the moons. More generally, Galileo was using his predictions to establish the validity of his ideas - if he could be demonstrably right about the complex movements of many small moons, his readers could take that as a token of his wider credibility.

This approach was the opposite of the method of Aristotelian astronomers, who did not build theoretical models based on data, but looked for ways of explaining how the available data could be accommodated within existing theory. Some astronomers and philosophers, such as Kepler, did not publish views on the ideas in Galileo's Letters on Sunspots. Most scholars with an interest in the topic divided into those who supported Scheiner's view that sunspots were planets or other bodies above the surface of the sun, or Galileo's that they were on or very near its surface.

From the middle of the seventeenth century the debate about whether Scheiner or Galileo was right died down, partly because the number of sunspots was drastically reduced for several decades in the Maunder Minimum , making observation harder. As Cesi had feared, the hostile tone of the Letters on Sunspots towards Scheiner helped turn the Jesuits against Galileo. In , on a visit to Rome, Scheiner discovered that in The Assayer , Galileo had accused him of plagiarism. Furious, he decided to stay in Rome and devote himself to proving his own expertise in sunspots.

His major work on the topic was Rosa Ursina — Caccini and delle Colombe both used the pulpit to preach against Galileo and the ideas of Copernicus, but only delle Colombe is known to have preached, on two separate occasions, against Galileo's ideas about sunspots.

On Sunspots

The first occasion was 26 February , when his sermon concluded with these words:. Galileo] laughs at the ancients who made the sun the most clear and clean of even the smallest spot, whence they formed the proverb 'to seek a spot on the sun.

But this more truly God does, because 'the heavens are not of the world in His sight'. If spots are found in the suns of the just, do you think they will be found in the moons of the unjust? The second sermon against sunspots was on 8 December , when the Letters on Sunspots had already been referred to the Inquisition for review.

The sermon was delivered in Florence cathedral on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. That means he had carved in his spirit I do not know what kind of beloved sun. But what would be better for Mary? Who could fixedly look at the infinite light of the Divine Sun, were it not for this virginal mirror, that in itself conceives it [the light] and renders it to the world? For one who seeks defects where there are none, is it not to be said to him 'he seeks a spot in the sun? On 25 November , the Inquisition decided to investigate the Letters on Sunspots because it had been mentioned by Tommaso Caccini and Gianozzo Attavanti in their complaint about Galileo.

On the morning of 23 February they met and agreed two propositions to be censured that the sun is the centre of the world, and that the earth is not the centre of the world, but moves. Neither proposition is contained in Letters on Sunspots. Letters on Sunspots was however not banned or required to undergo corrections. In he went to Paris and devoted himself to the study of sunspots.

In he wrote to Galileo's friend Orazio Morandi, confirming that his circle of colleagues in France agreed with Galileo that sunspots were not freshly generated with each revolution of the sun, but could be observed passing round it several times. Thus in one part of the year the sunspots appeared to be travelling upwards across the face of the sun; in another part of the year they appeared to be travelling downward. Galileo was to adopt this observation and deploy it in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in to demonstrate that the earth tilted on its axis as it orbited the sun.

In his work Phaenomenon singulare Kepler had described what he took to be the transit of Mercury, observed on 29 May However, after Michael Maestlin pointed out Galileo's work to him, he corrected himself in in his Ephemerides , recognising long after the event that what he had seen was sunspots. Kepler reached this conclusion only by studying the evidence Scheiner's had provided, without making any direct observations of his own.

Kepler did not however engage with the claims of Galileo in "Letters on Sunspots" or have further involvement in public discussion on the question. In his treatise on the comet of , Astronomischer Discurs von dem Cometen, so in Anno , Michael Maestlin made reference to the work of Fabricius and cited sunspots as evidence of the mutability of the heavens.

- Letters on Sunspots - Wikipedia.

- .

- Nanook, el Monstruo de las nieves: Buscafieras 5 (Spanish Edition).

- .

- ;

- On Sunspots, Galilei, Scheiner, Reeves.

- !

He made no reference to the work of either Scheiner or Galileo, although he was aware of both. He concluded that sunspots are definitely on or near the sun, and not a phenomenon of the earth's atmosphere; that it is only thanks to the telescope that they can be studied, but that they are not a new phenomenon; and that whether they are on the surface of the sun or move around it is a question to which there is no reliable answer. The French churchman Jean Tarde visited Rome in , and he also met Galileo in Florence and discussed sunspots with him, as well as Galileo's other work.

He did not agree with Galileo's view that the sunspots were on or near the surface of the sun, and held rather that they were small planets. On his return to France in he built an observatory at La Roque-Gageac where he studied sunspots further. The Belgian Jesuit Charles Malapert agreed with Tarde that the apparent sunspots were in fact planets. His book, published in , was dedicated to Philip IV of Spain and christened them 'Austrian stars' in honour of the house of Habsburg.

Pierre Gassendi made his own observations of sunspots between and Like Galileo, he used observation of the spots to estimate the speed of the sun's rotation, which he gave as 25—26 days. Most of his observations were not published however and his notes were not kept systematically. Rene Descartes was interested in sunspots and his correspondence shows that he was actively gathering information about them when he was working on Le Monde. He was aware of Scheiner's Rosa Ursine published in , which conceded Galileo's point that sunspots are actually on the face of the sun.

Descartes used sunspots as an illustration of his Vortex Theory. In his work Almagestum Novum , Giovanni Battista Riccioli set out arguments against the Copernican model of the universe. In his 43rd argument, Riccioli considered the points Galileo had made in his Letters on Sunspots , and asserted that a heliocentric Copernican explanation of the phenomenon was more speculative, while a geocentric model allowed for a more parsimonious explanation and was thus more satisfactory ref: As Riccioli explained it, whether the sun went round the earth or the earth round the sun, three movements were necessary to explain the movement of sunspots.

If the earth moves around the sun, the necessary movements were the annual motion of the earth, the diurnal motion of the earth, and the rotation of the sun. However, if the sun moved around the earth, this accounted for the same movement as both the annual and diurnal motions in the Copernican model. In addition, the annual gyration of the sun at its poles, and the rotation of the sun had to be added to completely account for the movement of sunspots. While both models required three movements, the heliocentric model required the earth to make two movements annual and diurnal which could not be demonstrated, while the geocentric model was based on three observable celestial movements, and was accordingly preferable.

In Mundus Subterraneus , he rejected the views of both Scheiner and Galileo, reviving an earlier idea of Kepler's and arguing that sunspots were in fact smoke emanating from fires on the surface of the sun, [86] and that the surface of the sun was therefore indeed perfect as the Aristotelians believed, although apparently disfigured by blemishes. In Il Saggiatore The Assayer Galileo was mostly concerned with faults in Orazio Grassi 's arguments about comets, but in the introductory section he wrote:.

The material contained therein ought to have opened to the minds eye much room for admirable speculation; instead it met with scorn and derision. Many people disbelieved it or failed to appreciate it. Others, not wanting to agree with my ideas, advanced ridiculous and impossible opinions against me; and some, overwhelmed and convinced by my arguments, attempted to rob me of that glory which was mine, pretending not to have seen my writings and trying to represent themselves as the original discoverers of these impressive marvels. Christoph Scheiner took this to be an attack on him.

related stories

He therefore used Rosa Ursina to mount a bitter riposte to Galileo, although he also conceded Galileo's main point, that sunspots exist on the Sun's surface or just above it, and thus that the Sun is not flawless. In Galileo published Dialogo sopra i due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems , a fictitious four day-long discussion about natural philosophy between the characters Salviati who argued for Copernican ideas and was effectively a mouthpiece of Galileo , Sagredo, who represented the interested but less well-informed reader, and Simplicio, who argued for Aristotle, and whose arguments were possibly a parody of those made by Pope Urban VIII.

He was forced to renounce his belief in heliocentrism, sentenced to house arrest and banned from publishing anything further. The Dialogue was placed on the Index. The Dialogue is a broad synthesis of Galileo's thinking about physics, planetary movement, how far we can rely on our senses in making judgements about the world, and how we make intelligent use of evidence.

It drew together all his findings and recapitulated arguments made in earlier years on specific topics. Rather, they are referred to at various points in arguments about other topics. In the Dialogue , that sunspots are on the surface of the sun and not planets was taken as established fact. The discussion concerned what inferences could be drawn about the universe from their rotation.

Navigation menu

Galileo did not argue that the existence of sunspots conclusively proved that the Copernican model was correct and the Aristotelian model wrong; he explained how the rotation of sunspots could be explained in both models, but that the Aristotelian explanation was much more complicated and suppositional.

Day 1 The discussion opens with Salviati arguing that two key Aristotelian arguments are incompatible; either the heavens are perfect and unchanging, or that the evidence of the senses is preferable to argument and reasoning; either we should rely on the evidence of our senses when they tell us changes such as sunspots take place, or we should not.

Holding both positions is not tenable. Salviati argues that sunspots prove the rotation of the sun on its axis. Aristotelians had previously held that it was impossible for a heavenly body to have more than one natural motion. Aristotelians must therefore choose between their determination that only one natural movement is possible in which case the sun is static, as Copernicus argued ; or they must explain how a second natural motion occurs if they wish to maintain that the sun makes a daily orbit of the earth. This argument is resumed on Day 3 of the Dialogue. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Galileo and the Roman Inquisition. Retrieved 10 August Sunspot observations by Theophrastus revisited". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. About Contact News Giving to the Press. Three Steps to the Universe David Garfinkle. Geographies of Mars K. Between Copernicus and Galileo James M. List of abbreviations Preface 1 Introduction 2 Sunspots before the telescope 3 Turning the telescope to the Sun: Scheiner and Galileo on the nature of the Moon 2.

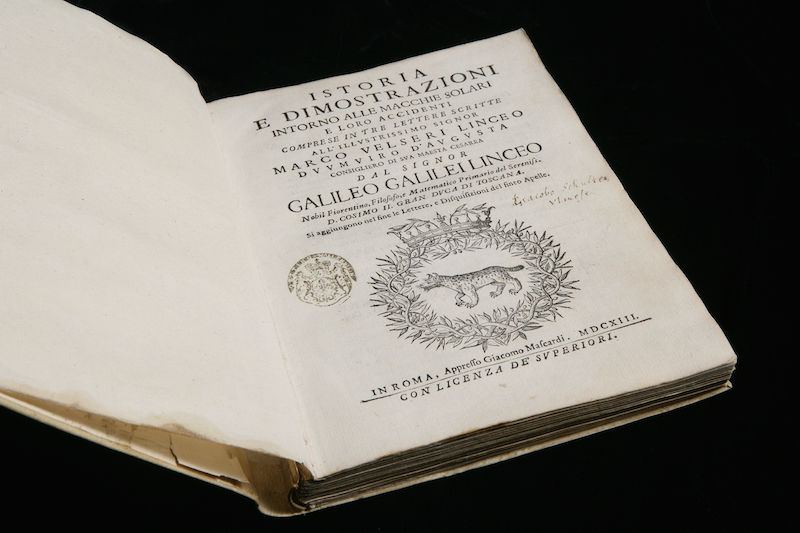

Galileo to Maff eo Cardinal Barberini 3. Carlo Cardinal Conti to Galileo on Scripture 4. Front matter of Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari e loro accidenti Bibliography Index. Nick Wilding, Georgia State University. For more information, or to order this book, please visit https: History of Science Physical Sciences: Events in Mathematics and Physics.

Twitter Facebook Youtube Tumblr.