So Roger Payne is right: But is their musical culture going downhill? These work for scientists and musicians because many of the sounds made by animals have a distinct form and structure, but not the usual tones and rhythms of human music, which are the only sounds musical notation can translate into images. A flat horizontal line in a sonogram means a steady clear pitch, a vertical line means a clap or a rhythmic hit, and a busy, beautiful image of many layers and patterns means a sound with complex overtones and a noisy character — just the kind of thing that eludes easy description.

But even these sonograms can look daunting to the uninitiated. I asked the digital designer and data visualizer Michael Deal to try his hand at simplifying these instantly generated images, colour-coding them in order to reveal the alien but organised structure of humpback whale song. Already in Roger Payne and Scott McVay realised the song had a hierarchical structure, but since their initial publication of this fact, no one has really tried to improve upon their visualisation using the dynamic and interactive techniques now available to us.

Such complex animal songs are actually quite rare in nature, but at such levels of beauty, there are strange parallels. Speed up a humpback whale song and it sounds surprisingly like the song of a thrush nightingale, with a similar balance between rhythms, jumps and long clear tones. In neither case can we accurately explain why such a song needed to evolve so extensively. But aesthetically, there are definite parallels. Does such a parallel mean anything? Perhaps there are basic principles at the root of what different species understand to be beautiful.

Evolution, as Charles Darwin knew well, is much more than survival of the fittest, but it also includes survival of the beautiful, through sexual selection, which is supposed to explain why whale songs are so long and moving, even though we have yet to see a female whale show any reaction to it. Though humpback whale song did not evolve for humans to appreciate, it may be no accident that we are its best audience.

The beautiful has evolved in the same world we have evolved, and this may be one reason we are always drawn to nature. But what does it take to record the best whale songs? One must have time a lot of it to go out on the water, drop your hydrophone deep down, get ready to listen, and to wait. Film crews rarely have the time to get the best, and scientists often have too much to do and not enough days in the field. Some of the best recordings have been made by Paul Knapp , who spends winter and spring in the Caribbean, camping on a beach in Tortola and quietly taking visitors out to listen to humpback whales.

I went slowly and with respect to the spot I always go to listen at the mouth of the bay. I think he was used to me by then and used to the sound of my engine. The whole moment made sense.

But I keep coming back — waiting, listening. People all over the world are taking whale songs apart in the laboratory, but only Paul goes out every day just to listen. He has no desire to get too close to the whales he is hearing. Those whales sound pretty stressed out to me. No one who hears these darkly beautiful tones for themselves can easily forget them. Far fewer scientists are now studying humpback whale song than in the heyday of its popularity in the s. The beauty of the song helped galvanise worldwide support for a global moratorium on whale hunting passed by the International Whaling Commission in , but since then the population of humpback whales has rebound to a fairly healthy level.

More by gimletmedia

A researcher working in the spirit of Payne and McVay, Adam appreciates the beauty of the song and has worked for years in the muddy waters off Madagascar to make the best possible recordings. When not working on whales he is also researches the indigenous music of this island nation, and he is not afraid to tackle some of the toughest problems in humpback song research, such as: It turns out that no one really knows.

No humpback has survived in captivity long enough for anyone to examine the process closely. But Olivier and his team have just published the first attempt at a model of the song production process that might explain how the whales do it.

,445,291,400,400,arial,12,4,0,0,5_SCLZZZZZZZ_.jpg)

Crucially, no air leaves the whale while he sings. This might make the humpback whale the greatest circular breather the Earth has ever known. He also believes that he might be able to solve the mystery of how whales can change their songs so rapidly, all together, across a single vast ocean over a rapid period of time. They move and sing much farther and faster than anyone previously thought. The selection of songs on our Important Records compilation will come from many places.

Playing with Whales

Glen Edney, formerly a whale watching tour operator in Tonga, contributed one beautiful hour long song. Paul Knapp, my favourite recordist, declined to let us use his song, which I personally still consider the best, although you can get it from his web page. I offer my own recording made unusually in Hawaii in very shallow, muddy water, just after a storm, when one lone male was singing close to the shore in Kihei. These conditions explain why there is very little background noise on this recording, and what little there was I took out.

Underwater can be a noisy place, especially from the perspective of a hydrophone, which can pick up the ubiquitious crackling noise of snapping shrimp, the thrum of boat engines up to ten kilometers away, and the rubbing of cables and anchors against the boat itself. In fact, most underwater whale recordings feature many whales, and they sound like overlapping insect choruses more than clear solos.

But noise reduction software is pretty advanced today, and can almost automatically remove continuous frequencies that get in the way of what we want to hear. And of course, given that these songs can go on for hours, how do you decide how much to release? I would like to offer up many hours of a single performance, to encourage a human audience to get into whale time, to slow down, to try to take the whole song in at an extended scale beyond the usual senses of our own species.

In concerts when I play along with whale song, I usually do it for only five to ten minutes, but I want to do it for at least 30 minutes, maybe a whole hour, to really change the way audiences sense what more-than-human music can be. Some of these sounds strain the limits of human aesthetic sense.

Booming lows too deep to relax with, leaping suddenly to high screams, constitute vast contrasts in our emotional perceptions. A few years ago humpback brains were found to contain a kind of cell called a spindle neuron that previously was only known to appear in the brains of higher order primates, those animals thought to be able to experience complex emotions. This means that whales can be counted as members of a small club, of which we and chimpanzees are both members. It is most likely in these deep and complex songs that the whales let loose the widest range their feelings can contain.

Once I remember my friends in Hawaii — many of them devotees of a dream of getting back to nature that sometimes includes living off of fruit and nuts and sleeping naked in a hammock for weeks in a valley in Kauai — were shocked that I believed one could mess around aesthetically with something as great and pure and sacred as humpback whale song by playing and performing with it.

Coast of Peru was taken from the logbook of the Nantucket whaleship, Bengal, Its title calls to mind the original Moby-Dick, Mocha Dick, a rogue albino whale that roamed South American waters and was said to be impossible to capture. Disinterred, these raw songs reek of an industry predicated on plunder and death. They could be stuck on the other side of the world, shipwrecked, eaten by cannibals. I was trying to get some fairly brutal-sounding musical background, rather than use the straight traditional sound.

- Whale Song.

- Third Time Lucky (The Coxwells Book 1).

- Lost Chords and Christian Soldiers.

- The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order;

- The U-Boat War In the Atlantic - Volume III: 1943-1945 (The Third Reich From Original Sources).

So we just went with electric guitar, concertina and drum kit. The idea was to create a fairly fluid feel around the music. These songs were the soundtrack to the first global industry.

Whaleships bore men of every nation around the world. Portuguese and Azorean sailors brought the lilting sadness of the fado traditional ; Scottish and Irish whalers contributed a Celtic legacy. American ships often carried freed African slaves; British crews included Aboriginal Australians and Maori. A modern ethnomusicologist would find traces of their cultures in these songs, too.

In many ways, this was the first multicultural art, produced by a bringing together of peoples in the colonial explosion of the industrial revolution. Out of hardship and, yes, courage came their songs — a potent, plangent legacy that we are still discovering, as the Kings of the South Seas so lustily declare. The self-titled album is released on 17 November.

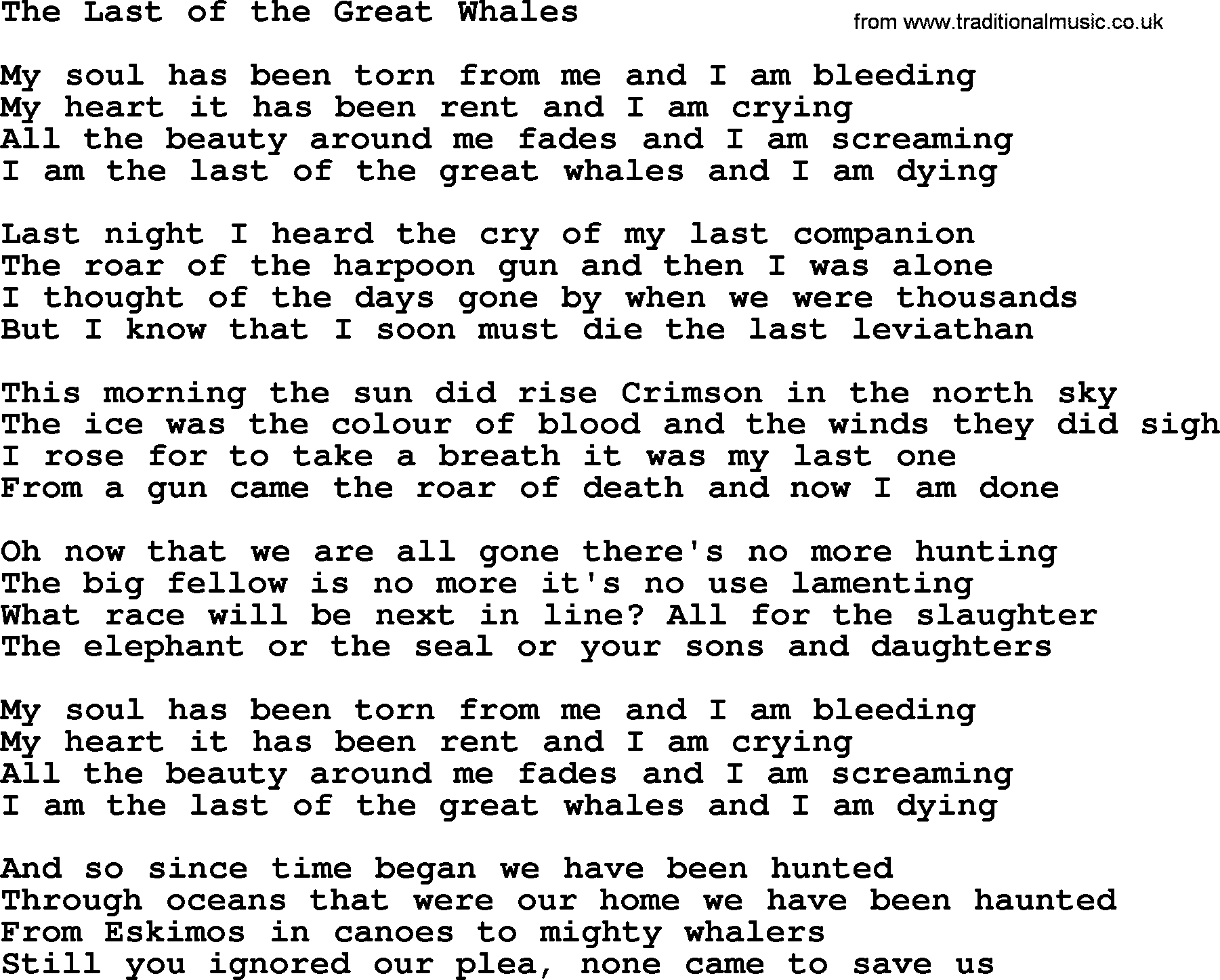

Some pop songs about whales. | Thousand Mile Song

This article contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our journalism is independent and is in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. The links are powered by Skimlinks. By clicking on an affiliate link, you accept that Skimlinks cookies will be set.

Whaling Marine life Whales History features.

Order by newest oldest recommendations. Show 25 25 50 All. Threads collapsed expanded unthreaded. Loading comments… Trouble loading?