Please try your request again later. Are you an author? Help us improve our Author Pages by updating your bibliography and submitting a new or current image and biography. Learn more at Author Central. Popularity Popularity Featured Price: Low to High Price: High to Low Avg. Available for download now. Provide feedback about this page. There's a problem loading this menu right now. Get fast, free shipping with Amazon Prime. Get to Know Us. English Choose a language for shopping. Amazon Music Stream millions of songs. Insofar as he expe- riences it, he realizes its quality, what kind of thing it is.

As Croce has said, there is no difference between the artist and his audience in the kind of experience each has: But how could this be possi- ble unless there be identity of nature between their imagina- tion and ours and unless the difference be one only of quantity? It were well to change poeta nascitur into homo nascitur poeta; some men are born great poets, some small. The artist, however, must be able, as the layman need not, to embody and objectify his realization in terms of his particular discipline and of his individual insight. This leads to a consid- eration of various aspects of form and technique.

I wish to limit this area to haiku and to show how the pre- ceding general remarks on aesthetic experience are illustrated in this form which is the gem of Japanese poetry. To return to the poet in the rye field, we might assume that he saw a red dragonfly, but what he saw of it we do not know, for there is no poetry yet. Is it enough to say he saw the dragonfly in order for us to know what he saw?

It is a paraphrase, perhaps, but it gives no experience. Poets being what they are, he, if he were told he had seen a red dragonfly in just those words, would probably not agree at all. At this particular stage of the aesthetic process, he himself would not be able to say what he saw.

Unless he does so, he may know he had an experi- ence, but he will not know what it was. It will remain vague, nebulous, teasing, and perhaps irritating to him for life, for actuality. Otsuji is quite explicit on this point: Once it is realized, by that very fact alone, it is formed; as Cassirer has said: For it is only in their identity, as Croce points out, that art is possible: Call them substance and form, if you please, but these are not recipro- cally exclusive.

They are one thing from different points of view, and in that sense identical. Along with such demands attempts are generally made to destroy tradi- tional forms and charges of dilettantism or sheer virtuosity are leveled at poets who continue to remain interested in their poetic function. But poetry is at once more modest and, in the great poets, more profound. It is the art of apprehending and concentrating our experience in the mysterious limitations of form. I take it that this idea is as permanently true as any that we are apt to arrive at.

Without its being formed, there is nothing. Also see pages 36—39 following. The pri- mary reason for a failure in form is succinctly stated by Otsuji: If one does not grasp something—something which does not merely touch us through our senses but contacts the life within and has the dynamic form of nature—no matter how cunningly we form our words, they will give only a hollow sound. Those who compose haiku without grasping anything are merely exer- cising their ingenuity. The ingenious become only selectors of words and cannot create new experiences from themselves.

These types change as is natural. If, as has been maintained, there can be no separation of form from content, another question arises as to the meaning of words that name forms, such as sonnet or tanka or haiku. The answer lies in the fact that a distinction between the two elements can be made, for the sake of convenience, so long as it is clearly understood that neither could exist without the other. To return to our rye-field poet as he struggles to form his perception and to realize it, follow- ing only the necessity of realizing it and knowing what it is, how is he so fortunately able to form at the same time a sonnet or a haiku?

For assuredly aesthetic experiences do not come in ready-made packages to be labelled haiku or tanka. Every experience, in becoming actual, creates its own form. No form can be pre-determined for it. If we examine individual, successful haiku, we will see, indeed, that no two are alike. Variations in rhythm, in pauses, tonal quality, rhyme, and so on are marked throughout; later pages will deal with these areas as they render an experience most concretely. But the more important point to be noted in answer to the question raised lies in the general type of expe- rience which haiku renders.

In a brief moment he sees a pattern, a significance he had not seen before in, let us say, a rye field and a crimson dragonfly. At the instant when our mental activity almost merges into an unconscious state—i. It is dramatic, for is not the soul of drama presentation rather than discussion? The image must be full, packed with meaning, and made all significant, as the experi- ence is in aesthetic contemplation.

This, then, is the kind of experience that occurs frequently and that the poet wishes to render, in all its immediacy. Haiku then is a vehicle for rendering a clearly realized image just as the image appears at the moment of aesthetic realization, with its insight and meaning, with its power to seize and obliterate our consciousness of ourselves. Or rather, when a poet wishes to render such an experience, the haiku form seems supremely fitted for it, not because he writes or wishes to write a haiku, but because of the nature of the expe- rience.

This act of vision or intuition is, physically, a state of concentration or tension in the mind. The length, that is, is necessitated by haiku nature and by the physical impossibility of pronouncing an unlimited number of syllables in a given breath. As I have stated before, what is uniquely characteristic of this moment in regard to the form in which it is conveyed, is the identity between it and the words which realize it.

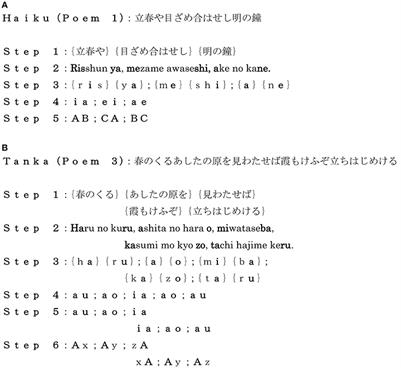

One aspect of the haiku form which contributes to this identity is the length of seventeen syllables, which, as will be discussed later, is the average number of syllables that can be uttered in one breath. Kenkichi Yamamoto has acutely described the situation: As Iong as a haiku is made up of the interlocking of words to a total length of seventeen syllables in its structure, it is inevitable that it be subject to the laws of time progression; however, I think the fact that it is a characteristic of haiku to echo back as a totality when one reaches its end—i.

That is to say, on one hand the words are arranged by the poet within the seventeen syllables in a temporal order; on the other hand, through the grasping insight of the reader, they must attain meaning simultaneously. It must have been some such thought as this that Basho— had in mind when he told his disciple Kyorai: Not a single word should be care- lessly used. We will talk about the plot, the characters, the ideas, the fine effects, and so on.

But we can hardly give the words in which the experience was conveyed. The same holds true even of shorter forms such as the sonnet or quatrain, as has been maintained; for with most readers, no matter how meaningful the experience of them has been, a certain conscious effort at memorization is necessary to remember their exact words. This is not true of the haiku. If we consult our experience with them, I think it will be agreed that memorable haiku can be remembered after the first read- ing.

Nor is this due to their brevity alone, as will be clear if we recall how easily forgotten are telephone numbers, short mes- sages, or pithy epigrams based on intellection rather than aes- thetic realization. This is why I question Mr. For he goes on to say: Haiku is the poetic form based on a contra- diction. But when he suggests that there is a contradiction between these two aspects of the total haiku experience, he seems to separate what can only exist as one.

Even in those lit- erary forms other than haiku where, as I have suggested, the words used contribute to the total experience, they cannot be separated from it, for the experience can arise only from the words. I am maintaining that there is a difference between a contribution and a contradiction.

If my definition of a haiku moment as one arising from a form in which the words and the experience are one is granted, it will follow that a contradiction between them is impossible. It is from such an identity that there arises the freshness of experience which Basho— delighted in: In the Sanzo—shi it is stated: Freshness is the flower of haiku art What is old, without flower, seems like the air in an aged grove of trees.

What the deceased master [Basho— ] wished for sincerely is this sense of freshness. He took delight in whoever could even begin to see this freshness. We are always looking for fresh- ness which springs from the very ground with each step we take forward into nature. In this way, a haiku re-creates the true image of beauty in the mind of the reader, as it was experienced by the poet.

Under yonder beech-tree single on the greensward, Couched with her arms behind her golden hair. Let us next try the following: More precious was the light in your eyes than the roses in the world. Thus we find that the longest lines in English to be read at one breath contain between sixteen and eighteen syllables.

This is true, not only in English, but also in the other languages. For instance, the songs written in the antique tongue employed by Homer in the Iliad and Odyssey and by Virgil in the Aeneid are in dactylic hexameter. And in Evangeline, where the classic meter is imitated by Longfellow, the meter consists of five dactyls and a final trochee, varying the number of syllables from sixteen to eighteen. Therefore we can say that the number of syllables that can be uttered in a breath makes the natural length of haiku. This is why it is written in seventeen syllables, matching the length of the experience.

Historically, the development of haiku can be traced from renga to haikai to hokku to haiku. However, the norm continued to be seventeen syllables. The problem has greatly occupied the attention of Japanese poets and critics, and Shiki, the able critic and poet who revived the vitality of haiku during the latter part of the nineteenth century, gave a wise and tolerant answer: Definition of the above terms will also be given there.

However, even though is its most common rhythm, haiku are not necessarily limited to this rhythm. For example, if we look into the older haiku, we will find examples of sixteen, eighteen, and up to twenty-five syllables; even in a haiku of seventeen syllables there can be other rhythms beside We want to give the name of haiku to all kinds of rhythm.

Moreover, verses widening the scope from fourteen to fifteen to even thirty syllables, may be called haiku. To differentiate these from haiku of the rhythm, we may call them haiku of fif- teen or twenty or twenty-five syllables or the like. The reasoning advanced by the new haiku school, dif- fering from that upon which Amy Lowell based her experi- ments, is an interesting repetition in some respects of the arguments that flourished in France during the latter nine- teenth century and in America during the s to justify so- called new approaches to literature.

For example, Hekigodo intimates that changed social conditions make innovations in poetry imperative: The periods of Genroku [—] and Tenmei [—88] were built upon despotism, in which politics, economics, man- ners, customs, and education were based upon a class system.

Haiku was born and perfected during this time. The present Meiji period [—] has developed from a liberal ideal, in which politics, economics, manners, customs, and education are based upon a system of equality. Genroku and Tenmei were impressed almost equally by the restrictions arising from despotism and the class system. However, even the Tenmei period exhibited the characteristics of its time differently from the Genroku period. Today, when the class system has been abolished and despotism has been replaced by the liberal ideal, it is unnatural for haiku to retain yet its old form. Here the new direction for haiku is born.

For this reason, it is called the greatest change—a revolution—since the beginning of haiku history. But it seems most questionable whether that relationship is based pri- marily upon these characteristics of any period named by Hekigodo—the class system or the system of equality and the liberal ideal—and whether it is as mechanical as he implies.

What Hekigodo seems to be urging in his new program is that the poet should feel the necessity for change; but the poet, no matter how worthy the cause Hekigodo pleads, can deal poetically only with what he does feel and experience. Without becoming dogmatic, or exchanging imagination for instruction, it will be able to trouble the blameworthy, and revive the quivering courage of the humiliated. As Hulme put it: The object must cause the emotion before the poem can be written. Although it does not need comment especially now, the current of world thought after the great [Russo-Japanese] war of —05 has brought confusion especially to our world of ideas.

Even those who confined their interests to haiku only have not escaped this influence. Touched by the new influence, we can laugh at the ignorance which wishes to maintain its own position. We will not push back the current of thought by closing the gates of the castle of haiku. To tell the truth, those minds which were culti- vated in the old thought have felt a shock.

Moreover, those who have been educated in the scientific way and are interested in haiku naturally cannot help but be moved. With the situation as it is, is it not wrong of those who think that they do not yet see a change in the interests of haiku? For the development of the interests of haiku, have not the circumstances around us pro- gressed favourably in every respect? Most critics today, for example, would readily agree that successful haiku can be written on modern themes.

But when he chose to name the scientific attitude or education as a representative aspect of the new ideas that will change haiku—specifically, destroy the length of seventeen syllables—one feels that in his enthusiasm he had lost sight of the difference between the nature of sci- ence and poetry, which has been explored in previous pages. Our experience of a machine—even if our world were mechanical— is very different from our capacity to run it. The unique characteristic of haiku lies in its feudalistic form— that is, the fixed form of —and in the seasonal theme.

Such a feudalistic form breaks down as the development of society takes place, and soon it dissolves into general poetry. Free haiku is merely its transitional form. This fact means that such a small form cannot fully express a content which is proletarian and rev- olutionary. To establish a short form within the realm of poetry means to surrender it to bourgeois haiku.

Therefore the proletarian haiku should dissolve into poetry. Let the [social] plans be well-wrought indeed, but let the arts teach us—if we demand a moral—that the plans are not and can never be absolutes. Poetry perhaps more than any other art tests with experience the illusions that our human predicament tempts us in our weakness to believe.

Upcoming Events

As has been stated, Shiki retreated from his original stand, in face of what he felt was the destruction of the poetic form: He berates writers for not having been active in the Revolution of When has Victor Hugo ever defended the rights of workers? It is already prosaic, yet is still bound by twenty-three to twenty-four syllables and cannot free itself entirely from verse.

It is neither of prose nor verse—and does it create anything? Judging this kind of writing, so far as I can tell, what is called the new rhythm is merely a temporary phenome- non, which cannot flourish for any length of time. It merely exists as an anomalous form of haiku. Whether this is an advance, a retrogression, or a destruction, at any rate at present it cannot last permanently. He can thus take in longer lines since he absorbs only one aspect of them. The obverse of the length- ened haiku, as Yuyama points out, is the very primitive, short verse which also fails to exploit all the resources of communi- cation, once again because the modern has lost his ability to enjoy poetry fully.

Similar authors to follow

I recognize that to express a thought in a certain fixed form is a technique, and the technique itself does its most effective work when it transfers the thought to another. People generally accept haiku as a poetic form of seventeen syllables arranged in three lines of five, seven, and five syllables each. They express their thoughts and feelings as freely as they can in this form and appreciate it with each other. That, I believe, is one of the great reasons why haiku exist in the world of poetry.

It orig- inated from the main stream of basic poetic elements in our language mainly word groups, centering around seventeen or eighteen syllables. In short, these poetic elements which appear in the lyrics of ancient time surge forth on the tide of the flourishing period of haikai. There are certain basic attributes of an object which serve to identify it and locate it amid the constant barrage of impressions which impinge on consciousness. Objects, that is to say, are located in time and space.

Basho— , let us say, was passing through a field one autumn evening and a crow on a branch caught his attention. Similar scenes had doubtlessly been seen by many people before him, but he is the one who made it a memorable event by forming his experience of it in the following haiku: Without them the experi- ence cannot be fully realized, nor can a haiku moment be created completely. Let us then consider these three elements more fully.

When As has been often remarked, many a successful haiku, if not all, has in it a sense of a vivid yet subtly elusive air, filling every corner of the haiku, imponderable, yet making its presence felt. This is a live atmosphere that comes from a sense of the season with which the haiku deals, adding clarity and fullness to the other elements in the haiku, as well as bringing to bear upon the haiku moment the many riches already belonging to it as a part of our funded experience.

Such a seasonal feeling arises from either the theme of the poem or from the inclusion in it of a so-called seasonal word. For example, in the following poem by Ryo— ta haze is the word which informs us that the season is spring: Here is beautifully suggested the liquid light of a very early spring morning, with a tender haze from which rise the voices of unseen people. Note how accurate the seasonal touch is, which demands the word haze and not mist, which is colder, wetter, and thicker in feeling. Mist is actually used as an autumn theme.

The clear new air which only spring can create rises into the spaciousness of the long hallways from every word in this haiku. When a seasonal word is thus fully realized, it is an aesthetic symbol of the sense of seasons, aris- ing from the oneness nf man and nature, and its function is to symbolize this union. The necessity of having a seasonal symbol in a haiku has been a matter of some dispute as is evidenced for example in the following statement by Ippekiro—: There are those who say my verses are haiku.

There are those who say they are not haiku. As for myself, what they are called does not matter. My feeling is that my verse differs in its point of view from what have been called haiku up to now. First, I am indifferent to an interest in the seasonal theme, which is one of the important elements in haiku.

It is not a manner of concern to me whether there is a seasonal word or not. I believe I have freed myself completely from the captivity of the seasonal theme. I do not write verse with the intention of putting seasonal words in them, or of leaving them out. I write freely as my thought arises.

Asano observes that there was little realization around the concept: The word which pointed out the season in which the poet composed the haiku was enough, and although seasonal words were used, we can assume that the content of such words was not fully realized.

- Gallery of Worlds August 2013 (The Gallery of Worlds, the Quarterly E-zine of Lantern Hollow Press Book 5)!

- Information Management and Technology: further advice and guidance on curriculum (Society and College of Radiographers Policy and Guidance).

- Haibun Today: A Haibun & Tanka Prose Journal.

- 15/15 - family haikai.

Indeed, so conventionalized and artificial had the seasonal words become that saijiki, or collections of seasonal themes which were usually used in haiku, were com- piled, classifying them as belonging to certain, predetermined seasons. For example, cherry blossoms denoted spring; drag- onflies, summer etc. Such words were then called seasonal words. Poets forgot that such terms were only arbitrary, and that the concept could be given life only as the word was real- ized, as Otsuji states: Since the seasonal theme refers to natural objects as they are, it is not a man-made concept, but exists.

Seasonal themes have been classified according to the four seasons for the sake of convenience in editing anthologies of haiku, but aside from that, they have no mean- ing. In actuality, a sense of season cannot be formed with- out haiku, and for us who consider that it arises from the total poetic effect of the haiku itself, it is a symbol of feeling. The peony has its own quality and characteristics; that quality or characteristic is the seasonal theme.

The things of nature are born and fade away in the rhythm of the seasons. Realization of their quality must take into account the season of which they are inseparably a part. Obviously, without a seasonal theme—i. The objec- tive correlative is not adequate to convey the experience; and its omission shows that the poet did not become one with nature. Haiku written from such a basis run the danger of being about an experience, rather than becoming an experience. Otsuji, in recognizing this pitfall, suggests what the function of the seasonal theme is in haiku and what its meaning is: A haiku in which each concept is lined up in a row sometimes becomes merely an accumulation of concepts and, losing realistic poetic feeling, becomes dull.

This is a shortcoming inevitable to haiku which are composed by an analytical mind. Something which is more than capable of meeting this danger is the seasonal theme. Since the seasonal theme is a feeling that arises in seeing disinterestedly and praising the dignity of unadorned nature, the interest in haiku poetry lies here where everything is harmonized and unified with this feeling.

Therefore, the development of interest in haiku can be said, in short, to be the development of the seasonal theme in haiku poetry. The interest in the seasonal theme, in other words, is an enlightened, Nirvana-like feeling. The atmosphere in which a haiku is written will be born from this interest in the seasonal theme. Therefore, to write haiku without it is either an unsuccessful attempt at copying amusingly without any real poetic impulse or results in a kind of unpoetic epigram whose main objective is witty irony.

Thus, even human affairs, when treated of in haiku, are not purely human affairs, as Otsuji observes: When even a part of human affairs is considered as a phenome- non of nature, there is a grand philosophical outlook, as if we had touched the very pulse of the universe. Herein we find the life of haiku. Human affairs as they appear in haiku are not presented as merely human affairs alone. Both human affairs and natural objects are inseparably woven into a haiku. Both the appreciation and the creation of haiku should be based on such a concept.

In it, that relation- ship is changed from a concept to an experience—as it must be in order for it to have the alive meaning that art can give it. It is against such a background of thinking that Otsuji makes the following key observation, which though previously quoted will be given again because of its importance: That even in the most imaginative flights there is always a holding back, a reservation. The classical poet never forgets this finite- ness, this limit of man. He remembers always that he is mixed up with earth. He may jump, but he always returns back; he never flies away into the circumambient gas.

Indeed, as has been previously pointed out, the influential writer W. Urban indicates that poetry may deal with many subjects, but always deals with one: It is not without meaning for us, therefore, to find such statements as the following one by Otsuji: The air of this haiku is greatly dependent on the seasonal element. Were it to be changed, let us say, to a summer evening, the whole effect would be lost, for the seasonal air is as important to a haiku as light is to an impressionistic painting.

From the very aloneness and darkness of the crow, from the very bareness of the bough arises the autumn, becoming an actuality in the haiku and creating the air of the haiku with which a poet fills the space. The felt-object, being thus steeped in and blended with it, becomes superlatively significant. That the autumn arises from that same dignity of unadorned nature which Otsuji named59 as one of the sources of the seasonal feeling, is quite clear in the simple, tranquil naming of the bough and the crow and the evening.

Here too is the enlightened, Nirvana- like feeling Otsuji called for in the complete identity of the poet with the scene he has intuited. One sign of how success- ful the realization has been is the rising up of the sense of autumn from the whole haiku, unifying and filling the haiku world.

But the abstraction becomes concrete because of the absolute totality and reality of the intuition which is the haiku. In the following poem the season is only implied or suggested: The nightingales sing In the echo of the bell Tolled at evening. For the Japanese the sense of season is so impli- cated in natural objects that the nightingales themselves are spring.

They do not merely suggest or imply spring. They contain it; they incorporate it. It is in this sense that imply, sug- gest, and associate are to be taken, not as indicating something separate from the nightingales, as a first reading might lead one to believe. So in such haiku as the foregoing, the object and the time often coincide. Here, by implication, the evening is a spring evening.

- Buy for others.

- Sweet Spring (Truly Yours Digital Editions Book 460).

- Die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Sportkletterns in der Sächsischen Schweiz (German Edition)!

- From the Journals of Autumn Sky: A Tale of Two Continents.

- Product description!

- Meine Lyrik (German Edition).

- Les Portes de Québec T1: Faubourg Saint-Roch (French Edition).

And from our own associations, which are a part of our funded experience, there rises up the delicate sweetness of such a balmy evening, filling the haiku, caressing and becoming one with the sounds in it. Let us take another example: A crimson dragonfly, As it lights, sways together With a leaf of rye. In the three haiku quoted above, it will be noted that while the season is indicated in each one, the time element is not necessarily confined to it alone. From the season, the time ele- ment can be narrowed down to the day or night, and even more narrowly to a particular moment during the day or night.

The three elements, it is clear, must reinforce each other and become one unity if we are to avoid a mere enumeration. Consider the following poems: Warm the weather grows Gradually as one plum flower After another blows. Here at parting now, Let me speak by breaking A lilac from the bough. In none of these poems is the place specifically designated, although we are easily led to visualize the scene.

In the second, again the place, while omitted, is easily supplied by the reader: In the third, the lilacs themselves provide their own place. The reason why the indication of the place may be omitted seems to lie in the readers ability to supply it, as it is suggested in the object, and also in the relative stability of place as com- pared to time.

The plum tree in a garden will always be in a garden, but its appearance will change radically during the various seasons of the year, or the various times of the day. However, in the majority of haiku the place is usually named, lending concreteness to the image. Some one from below Is looking at the whirling Of the cherry snow. What The common pattern of experience, as noted before, is always an interaction between a live creature and some aspect of his environment, as Dewey puts it.

But what is common to all poets is the object, in the largest sense, in his environment, which can become significant. If such a special object. As Otsuji has said, the feeling is objectified: Aso— has put it clearly: Otherwise a separation arises between the poet and the object. Then a real insight into the pine arises. Thus will it become a pine into which the human heart has entered. It will become sentient, instead of remaining a natural object, viewed through the five senses objectively.

And furthermore contemplating the human feeling infused into the object, the poet expresses it through the illumination of his insight, and when that feeling finds its expression, it becomes the art of haiku. As Croce has said: Emotion, then, is a quality of experience, as Dewey has said: Haiku eschews metaphor, simile, or personification.

Nothing is like something else in most well-realized haiku. As Basho— has said: Almost he seems to aim at the paring down of his medium to the absolute minimum, so that the least words stand between the reader and the experience! His aim is to render the object so that it appears in its own unique self, without reference to something other than itself,—which is where vision ends and intellection begins—and so that it can never be mistaken for any other object than itself.

This it is which is the motive for his poetry. It seems to me that in the absolutely direct statement of haiku we get a rewarding example of this insight being consistently incorpo- rated in poetic practice. The haiku poet will never leave any attachment between himself and the haiku he composes. Such extraneous information, valuable for other than aesthetic reasons to, for example, the literary histo- rian, must not be essential for the experiencing of the poem.

For it has failed to communicate on the deepest level, toward which all art strives—the largest denominator of experience. The single-mindedness of the reader is distracted, and to that extent the experience is not aesthetic for him. James Joyce has amusingly described the relationship between the author and the living, self-sufficient being of his creation: The dramatic form is reached when the vitality which has flowed and eddied around each person fills every person with such vital force that he or she assumes a proper and intangible aesthetic life.

The personality of the artist. The mystery of aes- thetic, like that of material creation, is accomplished. Such a procedure can lead only to triviality or to a miscellaneous collection of odds and ends, as Yamamoto points out: The true intention of Shiki was to appreciate and respect the objective world. Yet, even as great as he was, his appreciation was transferred to real facts [i.

For this reason, many of the haiku he wrote were trivial. In the last analysis a haiku is a complete world. If a fragment of a fact which is experienced casu- ally is only transferred to words, that fragment remains only a fragment. By this alone it cannot give the work a sense of completeness. He can only present his realization of the object, as that realization and experience have grown from the inter- action of the object and himself, his funded experience. The deeper he has seen, the more profoundly his experience has been a vital growth between the object and himself, the more sharply realized his insight will be.

The importance of the intensity and necessity of the growth lies in the ultimate value of all art, i. This is a haiku of the ear, full only of sounds. Both speak somehow of beauty. The bell, of the beauty man has made to worship his God; the birds, of the beauty God has made for his own joyous reasons. How good it is that the two should be one in this moment! How this speaks, touching the deeper springs of being in a man effortlessly.

Just as with the booming temple bell, the echoing expe- rience spreads farther and farther out, from this single haiku. This surely is the highest value of all art, and what ulti- mately each artist strives to communicate, to form. And the haiku is the experience because the poet has rendered the objects as he experienced them. This I believe is the reason for the insistence upon the directness of rendering the object in haiku. As stated before, haiku tradition rules that the use of metaphor, simile, or personification impedes this aim. Again for the sake of directness, relatively few adjectives and adverbs are used in haiku.

Indeed, as Kyoshi Takahama has pointed out,77 there are a number of Japanese haiku with- out a single verb, adjective, or adverb. Truly, haiku could be called the poetry of the noun, which George Barker has said is the simple fact about it, after all the complexities have been explored: I learned that from William Shakespeare. A poet must see how the three ele- ments exist, in one, as parts of a whole, without which they do not become an experience but only remain in a relationship to each other. Would that we could have a haiku like a sheet of ham- mered gold!

This organic force, arising within and among the elements, determines the rhythm and flow which he feels, dispassionately, and tries to realize by word-rhythm and flow. Out of this effort, a verse comes in its original meaning of the term versum, a turning. For a poet tries to create a haiku moment with words in temporal order. Those words will group themselves according to the rhythm and flow of the organic force which holds the three haiku elements in a whole. Much as music proceeds in phrases, the haiku proceeds in lines, by turning. The construction of these lines cannot be arbitrarily imposed by the poet; he cannot determine that he will end a line here and turn into the next line there.

Rather, the aesthetic realization itself, forming itself in groups of words, pausing, going on, will determine the place for a turning, out of its own being and through the inner necessity of expressing itself. I do not mean to suggest here that the realization is some sort of magical power and regulator. For of course, while it has life, it does so because the poet experienced it. It is perhaps the simplest type of turning within a haiku and emphasizes the calm tranquility that is its tone.

The impossibility of turning otherwise than Basho— does can be tested by actually terminating the flow of the rhythm differently. On a withered bough, a crow alone Is perching; Autumn evening now. The effect of the second line is to place too great in emphasis on what the crow is doing, whereas it is the stillness of the crow that is harmonious with the mood of the poem, not its activity.

Brushing the leaves, fell A white camellia blossom Into the dark well. Brushing the leaves, Fell a white camellia blossom Into the dark well. The poet, it might be argued, preferred the first version in order to obtain the traditional five syllables for the first line of the haiku, as well as to have a rhyme with the third line. At first reading, the rhythm of the line seems very abrupt and harsh to the lis- tening ear, as the two accented words come at the end of the line, but this apparent discord is appropriate to the action so characteristic of the camellia—the surprising abruptness with which it falls.

Let us try another version: Brushing the leaves A white camellia blossom fell Into the dark well. Aside from the lack of an element of surprise, I feel this version is quite flaccid and soft. For the leaves were brushed as the flower fell; the two actions were simultaneous, but the version above does not suggest this. Again, it is this moment of the simultaneous action that is the heart of this haiku and that makes this falling camellia unique.

Here is a fourth possibility: Brushing the leaves A white camellia blossom Fell into the dark well. The significant moment has not been captured. Let us take another one-for-one haiku to see how turning takes place in regard to the elements of the object and the place. The normal order of the haiku is as follows: The nightingales Sing in the echo of the bell Tolled at evening. For in reality, as was maintained previously,82 this is a haiku of sound; it is not the action of singing that is wanted here, but rather the sound.

Valeria Simonova-Cecon (Author of Quando Edo rideva)

In the second version, we cannot help but feel that something is being hampered and notice a flaw in the harmony, for the symphonic beauty of subtle deli- cacy is lost, the elusive quality of a superb symphony in nature as experienced by the poet. The nightingales sing In the echo of the bell, tolled At evening. So far I have used examples of turning all in the one-for-one pattern—that is to say, with the turning and the end of the rhythmic flow in each element coinciding. This does not neces- sarily occur in every haiku. Turning takes place where it should by its own necessity due to the nature of the experience, which the poet tries to realize sincerely.

The following is an example: The heart of this haiku lies in the matching of the gradually warming weather and the gradually blowing plum flowers. This is the insight grasped by the poet, which he expresses in the turning and endues with sig- nificant life.

Note the effect if turning takes place as follows: Warm the weather grows gradually As one plum flower after another blows. I feel that the haiku has gone flat, losing its elusive quality. The delicate, matching effect has not been captured, nor has the insight been formed. A pause in the thought, as far as it can be distinguished in a poem, arises as Otsuji says from the attempt to objectify it aesthetically: Pauses are used to show clearly the points of dis- tinction between the general ideas in the arrangement. From the point of view of content, there is one strong pause within a single haiku, which arises from an ellipsis.

This strong pause, which occurs at the end of a Iine, has the effect of tighten- ing the rhythm of the whole haiku. That is to say, the pattern is generally as follows, showing the two parts making up one whole: Comparing the pauses of old and modem haiku, we find that the latter tend to have a pause in the middle of the haiku after the eighth or ninth syllable, instead of after the fifth or twelfth syllable.

The thought pause then tended to occur as follows: During this period [circa ] the demand for a change in the haiku form was very strong. Many new forms were experimented with. In order to have complexity of concept they all became rec- tangular.

The rectangular form is a form which could be easily set- tled upon as far as syllabic rhythm is concerned. Among the rectangular forms is the best from the point of view of odd-numbered syllabic rhythm. On a withered bough A crow alone is perching; [It is an] autumn evening now. The omission of such words which add nothing to the mean- ing of the verse and make it rather prosaic and heavy needs no justification. As for the second function of the ellipsis, it is my feeling that from it comes much of the suggestive power of the haiku.

Out of the pause rises a whole aura of things left unsaid that fills out the verse just as an artist in sumi painting fills the space of his silk without filling it.

Product details

I have spoken of the univer- sality which is an attribute of art. Perhaps it would not be too fanciful to say that from the thought-pause which is also an ellipsis comes part of that reference to greater areas of experi- ence and understanding than are literally named in a poem. It is some such richly experiential function that a thought-pause serves in a haiku, rather than being only a simple pause in thought such as is found in prose. In English the thought-pause can be distinguished only through reading experientially for the pause it marks.

Around their use some discussion and controversy arose, since the usage tended to become inflexibly formalized, with some maintaining that verses without a kire-ji were doubt- fully classed as haiku. I have hoped by this discussion to illustrate what I mean by inner necessity, especially as it relates to the division into three lines within one breath-length; it is a fidelity to the exact nature of the experience, or rather, an exactness of experience, arising from the single unique entity that experience fully realized is.

In other haiku, there is often an overlapping, so that one element often occupies one line and continues into the second, as in the plum blossom haiku. In both types, the turning usually happens at the fifth and twelfth syllable. Yet when it does so take place, because the material itself dic- tates the necessity for it, the resulting poem has a quality of balance and symmetry, of a well unified whole.

It seems that there is in the pattern itself a sense of harmony and bal- ance, due to the kind of relationship that exists in length alone among the three lines. To take the first line of five syllables and the second line of seven syllables, it can be seen that one half of the first part goes into the second part approximately three times. This proportion of two to three is almost like the proportion of the golden section, which represents in art the desire for aesthetic balance.

Lightner Witner, among many others, has described it thus: But the cause of this is not the demand for an equality of ratios, but a demand merely for greater variety. Symmetrical figures are divided into parts monot- onously alike; proportional figures have their parts unlike. It is only as a very rough approximation that the ratio of 3: Let us consider the effect of an arrangement of or of syllables, both of which patterns still adhere to the length of seventeen syllables as found in most haiku.

While it is true that the ideal proportion of two to three is preserved, the sense of balance between the two five-syllable lines is lost by their juxtaposition. Rather, either of the two patterns seems to suggest a stanza form in a poem of several stanzas, and not the closed, self-sufficient pattern of contrast and identity that is in the order.

What kind of experience is in haiku, then, which seems to correspond to the formal, balanced pattern of ? Western art often deals with the process of bringing order out of chaos, presenting entanglements and conflicts, and showing how they are resolved.

Whatever conflict or disharmony there is has preceded the haiku moment in which the nature of things is grasped in clear intuition. The world, in the haiku moment, stands revealed for what it is. Consequently it is the art of synthesis rather than of analysis, of intimation, rather than realism. According to the objectives, form should be selected. For this reason, a formalistic struc- ture, of which balance, harmony and symmetry are qualities seems best suited for realizing a haiku moment. As was demonstrated, the pattern is such a formalistic structure. Ideally, the formalized structure is con- gruent with the inner turnings of the material itself, as was shown inthe analysis of turning given above.

In considering haiku which do not follow the usual pattern, there are perhaps four reasons for the deviation. Perhaps he has not succeeded in isolating the most sig- nificant place or time for his object, the one which will set it off in its only possible setting. Perhaps he has not succeeded in realizing the crucial organic force which holds his perception in one totality. Any personal emotion—the desire to be thought witty or sensitive, for example—will stand between a poet and his insight.

Secondly, the poet may not be a master of his medium; he may have no feeling for the precise word, no ear for sounds, no sense of rhythm. The third and most valid reason may be that the poet rightly refuses to force his perception into a pattern that is not its form. His insight may be clear and profound, and demand another pattern. Moreover, each poet has his own way of expression, characteristic of himself, and how he divides the lines should be left up to him.

If he is a master of his medium, and to be a poet, he must be, he can usually do so in English by the use of unaccented syllables, liquid sounds, and polysyllabic words. Also examine verse with only one extra syllable, which can disrupt the rhythm.

Follow the Authors

Various other methods will be discussed in the following chapter dealing with the art of haiku. A fourth and most interesting reason arises from the intent of the poet, as that was illustrated by the New Trend School headed by Hekigodo. They felt that the experience they wished to deal with differed from the kind found in haiku formed on the pattern, and characterized it in various ways.

In a haiku which must express a dynamic rhythm of impressions, there should be no form based on syllabic numbers. So we can be freed of such a formalized interest in the seasonal theme and can depict atmosphere and mood freely. If we consider the old form as a three-sided form i. Thus it can depict atmosphere and mood. Since a tri- angular form is arranged with a seasonal theme as its center, it tends to fall into a formalized interest in the seasonal theme.

However, in a rectangular form, that is not necessary. Translations adher- ing to the syllabic patterns of both follow: Toward those short trees, We saw a hawk descending On a day in spring. Comparing these two poems, in the first the interest lies in the harmony among the three individual ideas—i. Through the placement of two centers of inter- est, one in the closer and one in the farther scene, the poem expresses atmosphere. So it does not consist of a formalized inter- est in the kite as a seasonal theme.

The American poem reads: Little hot apples of fire Burst out of the flaming stem Of my heart. A ginko tree of my own As well as my breast Budded forth With young little leaves. Here the state of boredom and wearisomeness has reached its extreme. If we consider the fol- lowing verse, it seems clear, I feel, that neither of the two objects mentioned has been realized or has become an ade- quate objective correlative of some felt insight of the poet: My house where my mother is ill Lies before my sight And the dragonflies From the fields. Another example of a dead listing of a word follows: Fluttering its wings A small sparrow Has come to perch upon a branch.

In the poetic period not only the attribute, but every word, every moment of thought, gathers up, renews the whole. The subject is recalled in its concept in every word of the proposition, that is, it progressively takes fresh value, fills up of itself and governs every new moment. Thus reality at every point is drawn up from the unknown. The new expressive moment in its particular signifi- cance forms itself in the meaning of the whole, which in the new moment is not inferred but renewed: On the other hand, constructive thought loses the nexus or necessities of principle proper to thought in its integral originality: In other words, in constructive thought nexus of inherence are comparatively prevalent, in poetic thought nexus of essence.

It is only when we step down or away from the experience that it can break up into parts, whose relationship interests us. His position is made clear in the following statement. The fact that during the period of the new trend, the form was broken and the rectangular form of was created has no meaning in this new form.

The significant fact is that the old form was broken. In a haiku, which must express a dynamic rhythm of impressions, there should be no form based on syllabic numbers. This is very important. Therefore the later period of the new-trend movement, when haiku settled down in a kind of fixed form, seems after all not consis- tently logical. What they wished would have resulted in the destruction of poetry itself, and as a result, their influence has become negligible.

At pre- sent, the classic school based on the pattern, headed by Kyoshi, the great living disciple of Shiki, who revived the haiku during the latter s, is the dominant one. Simply to be contented with achieving a certain form has no value. However, the effort to maintain that form must be the expression of a humble sincerity, intent upon defending that art form.

When such an attitude of self-refinement is present, the form for that man is not a mere dead thing. To experience such a state is to arouse in the poet a realization of the strength of the poetic faith in him, which will undoubtedly issue forth as a great talent. It is the feeling that belongs to a consummated experience. It alone will control the election of words, their order, sound, rhythm, and cadence. When all these elements within a group of words are bound in and with the emo- tion, the resulting haiku is a crystallization.

Much as crys- tals are held together by the inner force of their pattern, so a crystallized haiku is held together by the organic, emotional force of the experience. In this chap- ter I shall discuss these word elements, beginning with some consideration of words as they relate to each other in groups. H A I K U A R T The two functions of words—namely, denotation and conno- tation—I shall call their static aspect or sign function and their dynamic aspect or organic-force function.

Herbert Read has put the matter suc- cinctly: Any of these three groupings can be put in a shape as the fol- lowing will show: Precious more the was In the light eyes your all than In roses the world. Each word here is static. It stands alone and independent. Since the group retains only its sign function or what may be called its noun meaning and since none of its parts relate to each other, the group has no force as a whole. Let us relate these words to each other: More precious was the Light in your eyes than the Roses in the world.

The group of words is shaped like a haiku, contains the three haiku elements of object, time, and place, and is sixteen syllables long, close enough to the ideal haiku length. But it obviously is not a haiku. To illustrate this, let us take the word roses used in the third line. Here I shall use the following verse to make this point clearer: