I have a dream about woman pouring into all professions a new quality, I want a different world, not the same world born of man's need of power which is the origin of war and injustice. We have to create a new woman. LUl I IH- -. There is a quantity of work both from matri- archal prehistoric civilizations and by wom- en architects today which shows a prefer- ence for round or oval shapes.

Model of Maltese temple, B. Claude Hausermann-Costy, plan of con- crete-shell house. Margot Marx Offenbach , plan for socialized medical care facility. Margrit Kennedy, an architect and planner practicing in Berlin, is currently researching ecology, energy, and women's projects for the International Building Exhibi- tion in Berlin. Wekerle 'omen have special housing needs which currently are not being met by the open hous- ing market or by social pro- grams aimed at assisting disadvantaged groups.

They are, instead, being met by women themselves. This lack of concern was demonstrated at a recent self-help housing conference held in Berkeley. While discussion focused on the special needs of Hispanics, Blacks, farmworkers, rural residents, and center city dwellers, no one mentioned women as a prime tar- get for these housing programs. She reported that, in her experience, women face considerable dis- crimination in availing themselves of housing rehabilitation programs. Single mothers are frequently ruled ineligible for low-interest subsidized mortgage loans on the grounds that child support and AFDC are not "predictable" income.

Customers Also Bought Items By

Wherever "sweat equity" the person's own labor makes up for a low down payment, wom- en responsible for childcare may be ex- cluded on the grounds that they have little time left to renovate a building. Women's participation in self-help housing was not deemed a priority by conference participants. This is especially disturbing given that they represented a small but innovative housing movement, which celebrates individual initiative and collective solutions rather than reliance on mass housing developments and public housing.

In many areas of the country, re- habilitation of abandoned or deteriorated dwellings is becoming almost the only alternative for providing low- and moder- ate-priced housing. New units are too expensive and rents have escalated in re- sponse to rent control or its threat and the scarcity of apartments caused by con- version to cooperative or condominium ownership. Families headed by women experience the greatest difficulties in this housing market. By March , they numbered 7. Families headed by women are more likely than husband-wife families to have children under the age of 18, and one out of three lives below the poverty level, although more than half of the women work full- or part-time outside the home.

According to a recent HUD study, fami- lies headed by women are less well housed than the general population; they live in older housing, which is less well main- tained than the national average, and they are more likely to rent than own. They are also more likely to live in center city neighborhoods. The likelihood of living in inadequate housing increases if women are Black, Hispanic, or heads of large families. Besides having less money to support their families, these women are overtly discriminated against by land- lords.

Adequate housing costs a woman head of household a very much larger proportion of her income than it costs the average American. Women have started to take matters into their own hands. A recent develop- ment has been the emergence of several self-help housing projects directed exclu- sively at the housing needs of women heads of families. These projects, de- scribed below, have certain innovative features that are not generally part of other self-help efforts: In responding specifically to the needs of women heads of families, the concept goes beyond shel- ter and incorporates necessary supports such as counseling, skills training, and provisions for childcare.

Grass Roots Women's Program: A door-to- door survey of more than a thousand low- income households identified problems with existing services. Housing was one of the top priorities mentioned in the survey. The city is low density, mostly single family houses.

In going door-to-door, we found that wom- en are isolated, and often speak no Eng- lish; they are afraid to go out of the house. The concerns expressed included lack of available low- income housing in the community, rapid- ly escalating rents, and the fact that single women with dependent children often cannot find suitable housing and are sub- ject to rent gouging. The women wanted particularly to learn basic repair, main- tenance, and renovation skills. They felt that rehabilitation of existing deteriorated or abandoned houses was the only way for them to ever own a home.

Surveys made by CSD confirmed the severe problems identified in the work- shop. Of the 19 projects funded by the state's self-help housing program, this was the only one dealing exclusively with the housing needs of women. Key elements of the WISH proposal included information workshops on exist- ing government housing programs and available financing, classes in basic home repair skills, and plans to involve women in community development. The project had to be considerably scaled down due to delays in funding by the state funds were obtained in March , almost a year after program approval , changes in the housing market, and changes in the priorities of the sponsoring agency.

So far, one graduate of the program has started her own busi- ness doing minor home repairs for a fee. Wherever possible, WISH planned to use women instructors as role models. In real- ity they couldn't find women instructors with repair skills and experienced con- siderable difficulty hiring skilled trades- persons on a part-time basis. The program hoped to reach women and identified women heads of families as its primary target group. Vari- ous forms of outreach, such as notices in supermarkets and at community centers, were tried. Sylvia Rodriguez-Robles, Co- ordinator of the Grass Roots Women's Program, explains, "It took time to get women to come to class for something as nontraditional as fixing up their own homes.

In retrospect Rodriguez-Robles says, "When we started our energies were high, we were all geared up, but our priorities changed while waiting for funding a year later. Ac- cording to Rodriguez-Robles, it has taken considerable time and energy to launch a small, underfunded, short-term pilot proj- ect geared specifically toward meeting the housing needs of women while existing programs with more money and staff con- tinue to ignore women's needs.

She sug- gests that women's energies might be better spent in enforcing compliance so that programs with ongoing funding wili increase services to women. Community redevelopment, especially involving women in planning a neighbor- hood environment more conducive to their needs, has been a long-term objec- tive of the WISH program.

While brainstorming ideas for our housing repair program, we en- visioned a "redeveloped" neighborhood, with a strong sense of community support to the well-being of the family. This "re- developed" neighborhood would have a day-care center, a cooperative food mar- ket, public transit and social services at the neighborhood level. WISH has maintained community devel- opment as a priority. The City of San Bernadino has obtained funding from the Federal Neighborhood Housing Services Corporation for the revitalization of se- lected neighborhoods, and the Grass Roots Women's Program has been active- ly involved in the planning meetings, where they emphasize the need to include support services for families such as day- care and play centers for children.

The Building for Women Program for women ex-offenders operated by Project Green- hope in New York City has rehabilitated a house in East Harlem and gives women job training in repair skills. Un- der the terms of the loan, the women com- pleted all the interior demolition, site work, and finishing. The framing, roof, electrical, and mechanical systems were handled by professional contractors. In addition, the program has received funds to rehabilitate a city-owned store to be used for their office and shop space.

Building for Women has become a major community resource.

They are try- ing to obtain more funding to renovate other buildings on the block and create a climate which will encourage private re- habilitation. They have a contract to weatherize dwelling units for low-income tenants, home owners, and senior citizens. They teach carpentry, simple repairs, and furniture building to other women in East Harlem. This is a good example of a solution which serves several needs simultaneous- ly: They become reintegrated through their work on community buildings and classes for neighborhood women.

Instead of merely receiving assistance, they are in a position to offer a valuable service. Single Parent Housing Cooperative In the summer of , a group of nine single mothers formed to develop a single parent housing cooperative in Hayward, California. Rents in the city have doubled in the past few years, and heavy conver- sion of rental units to condominium hous- ing has made costs prohibitive for many single parents.

This project is now in the development stages: Funds from the HUD Com- munity Block Grant Program are paying for such pre-development expenses as site acquisition and architectural and staff fees. A large part of the effort to date has involved finding single parents who might be prospective residents, educating them in cooperative principles, and involving them in the initial planning process.

The developers spent three months publicizing the cooperative in places frequented by single parents— housing offices, welfare departments, day-care centers, and churches. This generated inquiries. Since late fall of , they have held community meetings every six to eight weeks with an average attendance of 35 to 50 single parents. Participants have discussed and ap- proved the guidelines for selection of resi- dents.

Architects Sandy Hirschen and Mui Ho of the Department of Architec- ture, University of California, Berkeley, are currently doing programming work with the staff and single parents. The plan is to develop a project which will house from 20 to 25 families and be supportive of their needs by incorporating childcare and a food cooperative.

Difficulties have been experienced in finding a suitable yet affordable site for the housing. Some Thoughts on Women's Self-Help Housing In the past, women's housing needs have not been a priority either of the housing industry or of government hous- ing programs. Nor has housing been an issue of the women's movement in the same league with health care or childcare.

None of the projects described here was started by professional feminists or even particularly supported by organized women's groups. The projects represent the grass roots initiatives of community women.

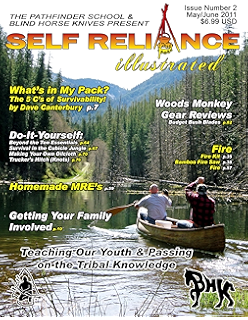

Self Reliance Illustrated Issue #1 by Dave Canterbury

Perhaps because low-income women heads of families are being so hard pressed in today's housing market, they have decided to help themselves, as no one else seems to care. In taking action, they have become much more demanding and visible. They are insisting that hous- ing programs and government agencies respond more directly to their needs. In HERESIES 15 fact, all of the women's self-help housing projects are affiliated either with govern- ment agencies or with other nonprofit community groups.

- Ways not to kill classroom creativity.

- FREE Digital Copy of Self Reliance Illustrated – JUST ASK!!

- .

- ;

Much as these organi- zations have ignored women's housing needs in the past, such coalitions help single mothers to overcome the consider- able obstacles relating to information, funding, and technical and organizational skills. Women, however, have learned the lesson of public housing and prefer to re- tain control and demand only the neces- sary resources to help themselves.

Women have much to gain by partici- pating in housing rehabilitation and self- help housing programs. They can acquire decent, safe, affordable housing which they control. They can be directly in- volved in the design of the unit and can include provisions for collective facilities and shared services; they can gain job experience and a sense of confidence in their own skills. The projects described here are impor- tant because they provide models of how women can use self-help to house them- selves and their children.

But each case also shows the obstacles that women face and the hard work that is required to get a women's self-help project off the ground. Women have the right to equal access to self-help and housing rehabilitation pro- grams — most of which are paid for by public funds. They must demand that existing laws like the Equal Credit Oppor- tunity Act , which bars sex discrim- ination in housing and in the receipt of benefits from Community Development- assisted programs, be effectively enforced.

Women must demand that self-help housing programs meet their needs. For instance, childcare should be included as a regular cost of any program. And finally, women must lobby for alternative home and neighborhood designs which will free them from total responsibility for their own family and from isolation in the home. Otherwise, self-help housing will only replicate patriarchal patterns, and the possibilities for real control by women over their housing environment will be lost. The addresses of the programs described are: Photograph by Gun Anderson.

Used by permission of Gun Anderson. We discovered several other projects in which women have begun to take an active role in the planning of housing and communities. In contrast to Wekerle's examples, three of the following efforts illustrate projects where architects themselves have taken the initiative in order to share their skills and knowledge in creating environments which are more sensi- tive to women.

Unique to all these projects, both those described by Wekerle and the ones that follow, is the premise that problems of housing and community are closely linked to all aspects of one's life — employment, transportation, day-care, and services. Whether the attempt to integrate these various facets of living is exclusively female is speculation at this point.

It ,s clear, however, that the women involved in these projects have all made a com- mitment to structuring an environment that is much more than the simple, safe dwelling unit. Women's Design Collective Susan Francis ithin the past several years in Great Britain women in the design and building fields have come together to discuss the design and production of buildings, as well as their personal experiences working in a predominantly male discipline.

The group that has formed as a result of these discussions maintains close and informal ties with the New Architecture Movement NAM , a na- tional network of radical architects and building users. Among other projects, NAM produces a bi-monthly magazine called Slate an issue of which was devot- ed to feminism and architecture last year. Initially our group of women held a series of open meetings to discuss sexism in the building press, to develop a critique of both the theoretical and practical work of particular women, to share our experi- ences of isolation and oppression at work and at home, and to promote dialogue on broader feminist issues.

In collaboration with several feminist anthropologists we organized a conference on "Women and Space," which brought together from all over Britain women from a wide range of related disciplines. Several groups with particular objectives emerged from the conference, including a team of women who are making a film. Another group is attempting to develop a feminist critique of buildings and space which recognizes the importance of the social and political context of both the organization of pro- duction and the design process itself.

Still another group, with a more prac- tical bias, has been working together as a feminist design collective. Consisting of about 20 women who are training or working as architects, this collective has undertaken various projects on a part- time basis. The projects have included renovating five terrace houses in South London into a refuge for battered women and their families, developing alternative proposals for a health care center endors- ing a report produced by several commu-. This last project was initiated with the specific intention of pro- viding opportunities for women who, for various reasons such as having children, find it difficult to register for government training courses.

The design collective produced drawings and written informa- tion for the conversion of a factory unit into a skills center. The building work was done by women tradespersons, with a variety of skills, who came together for first time from different parts of Britain. Some of these women are now teaching in the skills center and others have formed a women's building cooperative and are continuing to work together in the Lon- don area. The skills center project was funded jointly by the central and local governments. Whether funds for similar projects will be available in the future is in doubt, given the extensive cutbacks in public expenditure and the negative atti- tude toward women's engagement in pro- duction.

Despite the bleak economic outlook, some of us feel optimistic and very excited about working together. Within the de- sign collective different interests and con- cerns have been expressed; we expect these Panel designed by NAM Feminist Group, exhibited at the Beauborg, Paris. Some women hope to work closely with the building cooperative to break down traditional barriers between professionals and manual workers.

Other women hope to do applied research to develop a feminist approach to the design of space. Still others wish to concentrate on acquiring management and design skills in a more conventional manner. We hope to maintain links with the broader discussion group as a means of becoming more aware of the specific ways in which women are oppressed by patriarchal de- sign and use of space and as a means of fighting collectively for changes.

Towards a Femi- nist Critique of Building Design. Colombo's 1 arly in El Club del Barrio, St. This effort symbolizes the strug- gles of a Hispanic Community— primarily women — to survive and make a better life for themselves and their families. It illus- trates the process through which women, who might not identify themselves as fem- inists, can begin to gain some control over their lives.

Their conscious motive is to create a better life for their children, sug- gesting a certain female tenacity in the face of caring for and sheltering one's chil- dren. This is a morality play that has not ended; good has not overcome evil and the meek have not inherited the earth — as yet.

However, we do have players, a set- ting, and a classic conflict. The players are the Puerto Rican residents of a Newark neighborhood, the sisters of St. Columba's Church and School, the officials of the city of Newark, a large commercial devel- opment group, and the legions of gentrifi- cation waiting in the wings. I Lincoln Park area of Newark, N. Magnificent 19th-century townhouses and landmark churches rim the park. A half-block away is St. Church, a lovely Beaux Arts structure tucked into a tiny, triangular plot.

Across the street is the school which serves as a center for the community. Yet, as in other cities, this neighborhood has its abandoned, scorched buildings; it lacks a healthy economic Christine Lindquist base. In it was declared a redevelop- ment area, which brought the promise of future federal monies as well as possible gentrification or large-scale commercial development.

At this point the Neighbor- hood Club members decided to take mat- ters into their own hands. The conflict really begins in , when a development group started to re- habilitate nearby buildings for Sections and 8 occupancy federal programs which assist private sector development in target areas. Neighborhood residents were concerned by the poor quality of this work and by the fact that the buildings contained fewer apartments after rehabili- tation.

A group of concerned neighbor- hood women began to meet with Sister Deborah Humphries, who had just come to St. Columba's as a school social work- er. At first they discussed their children, The abandoned townhouse purchased by El Club del Barrio. Photo by Gail Price. They decided to take action and organize into two clubs: Madres en Accion and Madres Unidas.

Покупки по категориям

Initially the women taught each other such skills as cooking, guitar playing, and sewing in these self-help groups, which soon grew to include high school equivalency classes and numerous services related to employ- ment, food stamps, welfare, counseling, and translation. It became clear to them that the key problem was the housing crisis. The com- mercial development group was produc- ing appallingly poor housing and violating the rights of relocated tenants. Some ten- ants were given day eviction notices although the law requires 90 days. Other tenants were relocated three times while their buildings were rehabilitated, and not all tenants were able to return to their buildings because there were fewer rental units.

Those who could return to their "rehabilitated" buildings found such con- ditions as water running down walls, floors separating from partitions, un- dulating floors and stairwells, and tile floors in basement apartments which wore away to reveal earth underneath. During a discussion of his firm's work at the New Jersey School of Architecture, a representative of the developers main- tained that the neighborhood women's claims were greatly exaggerated; the buildings were old— what did those people expect anyway?

City Hall did not officially respond to the club's complaints. What help did come was meager. The Newark Housing and Re- development Corporation then completed a set of as-built drawings for the club to begin its work. The club has elected a board of direc- tors to oversee the project.

A modified sweat equity plan will be used in which the families will provide the unskilled labor, while carpenters, electricians, and plumbers will be paid. Finally, the six families have been selected and are now learning about the various complexities of self-help housing. We can be fairly certain that St. Columba's Neighborhood Club will suc- ceed in this housing venture, but one can only wonder how long people, especially women and children, are going to con- tinue to be pawns in various struggles for power. This story is an example of the dif- ficulty of putting feminist theory into practice.

We believe that we must seize control over our own shelters as builders, designers, and consumers. This project, as described, is only the difficult beginning of that process for these women. As one of the women said at the onset of the project, "It really is survival more than anything else. Aitcheson, and Joan Forrester Sprague Single, widowed, and divorced women represent roughly a quarter of this coun- try's population, and their numbers are increasing.

Yet housing opportunities are generally based on traditional assump- tions that not only lead to a denial of equal opportunity but also do not recog- nize new functional needs. Restrictive practices affecting the lives of many wom- en have served to minimize their self- respect, hindered their access to credit, impeded their gaining and retaining jobs, and, thereby, have also reduced their housing opportunities. Many women face the burdens of poverty.

Statistics show that on a national basis, most women who are heads of households live below pover- ty level. For six years before founding the nonprofit organization, the three of us had collaborated as architects and plan- ners. Through paid and volunteer proj- ects, private practice, and the founding and coordination with many other archi- tects and planners of the Women's School of Planning and Architecture, we dis- covered that we shared a concern for the way many issues affect women.

More- over, we shared an interest in becoming advocates to improve women's long-term housing and economic stability through the establishment of a nonprofit develop- ment corporation. Detailed planning for the corporation began in the fall of Funding was first sought from the U. As a result, in addition to continuing our architectural and planning practices, we prepared a comprehensive proposal for funding and submitted it to the Community Services Administration in January The Economic Develop- ment Administration was contacted short- ly thereafter.

Funding was granted by both agencies in October The Women's Development Corpora- tion's first program is located in Provi- dence, Rhode Island, more specifically in Elmwood — a multi-ethnic neighborhood in which more than half of the residents are single, widowed, or divorced women. The area currently has the state's highest percentage of families receiving welfare payments. The program includes plan- ning with neighborhood women who are single and heads-of-household for cooper- atively owned housing; it also provides means for women to gain housing-related skills and jobs, for example, in building construction and maintenance as well as housing management.

The self-selected core housing planning group four His- panic and eight Black women has met weekly in an intensive capacity-building program with the aim of assuming leader- ship roles within a larger housing planning group including others in the community. The majority of these women are in their twenties, with from one to eight children. This pro- gram is geared toward individual entre- preneurs and self-help groups at various stages of development, from pre-business to small business expansion planning. One self-help group receiving technical assistance from the program is the South East Asian Cooperative, a cottage handi- craft enterprise selling the works of over 50 Hmong women, recent immigrants to Elmwood from the mountains of Laos.

Another project entails revitalization of a commercial building for new businesses. The plan is to provide neighborhood- based jobs along with necessary support services such as day-care, building main- tenance, housing management, and food services on a subscription or cooperative basis , as well as workshop and office space for various enterprises and organi- zations. The broad aim of the Women's Devel- opment Corporation is to offer low- income women in a particular neighbor- hood of Providence a chance for stable housing within a support system network that encourages independence and self- sufficiency.

This is necessary for many women in both urban and rural areas around the country. The move from pov- erty and welfare status to having good housing and work opportunities is obvi- ously not an overnight or simple process, but the ability of many women at poverty level to balance scanty resources and raise their children shows tenacity, initiative, and imaginative budgeting — qualities that can become the basis for more productive lives in response to a new environmental network offering positive opportunities.

She also works with the Women's Development Project in Brooklyn. Susan Aitcheson, an architectural designer, coordinated several sessions of the Women's School of Planning and Architecture. Program participants learning about rtglazing windows in the building maintenance program. Providence buildings like this are being con- sidered for substantial rehabilitation. The interview was sandwiched between meet- ings with the tenants' group in the Newark public housing rent strike and with appli- cants for the design center's training pro- gram.

How did the community design cen- ter movement begin? The community design center move- ment began in Design centers grew out of the politics of the '60s and all the problems of the cities. The community de- cided what they didn't want and what they wanted to restore.

However, they didn't know if what they were dreaming about could be made real.

Dave Canterbury

They needed someone to help make the dreams feasible. That's where design Centers came in. When we first talked about your work you said you weren't an architect, but your work is so clearly architectural.

- FREE Digital Copy of Self Reliance Illustrated – JUST ASK! –?

- Lina e Gina (Italian Edition).

- My Trials: Living Life with Sugar Diabetes.

- Self Reliance Illustrated Magazine.

- Advertise « The Self-Sufficient Gardener.

- Self Reliance Illustrated Issue #1.

How did you get started with the design center? In the New jersey Society of Archi- tects was looking for someone who could relate to the community and relate to them. I had been involved in community actions. I had lived in public housing and had been involved in improving housing conditions for the poor because 1 was one of the poor.

But they were very picky. They checked all my references and inter- viewed me several times — to make sure I could do the job. Were you aware of architecture as an op- pressive force? Being one of the poor, architecture was one of the last professions I knew anything about. I would never have thought that an architect was responsible. I know now that architects do have a re- sponsibility and that there was a compro- mise in values and sensitivities.

I do be- lieve that most social problems begin with the physical environment. There is a con- sciousness you get as a child from what you see on TV and in school books. You wake up and you look around and begin to have negative feelings about yourself. The people living there take out their frus- trations on the buildings, not really know- ing why. I think architects have sold out. What kind of architectural work would you like to do — your ideal kind of project? You have to understand that the clients create the projects here.

We do advocacy planning and design. The poor are not in the business of building. We do mostly rehabs and neighborhood preservation. We are seldom privileged to build from scratch. We do some parks, mostly 50' x ' lots where a building has burned down. The people in the neighborhood convince the city to tear down the building.

We try to do green spaces and innovative play spaces, like climbing areas and little houses for children. I think I believe in ownership. I'd like to renovate a neighborhood, building by building, block by block, and do all the planning so tenants could do sweat equity and end up with a cooperative situation. I would like to see a self-sufficient neigh- borhood. I would do anything I could to get rid of public housing as it is now— under a housing authority.

Design, density, management, maintenance all have to be considered. I would have a lot more acreage and green space. I would also make them more sturdy so people could have permanent homes. The poor are here because of the capitalistic system; they are not going to go away. They need to have more choices. I say down with the high-rise. Give us open spaces and stop piling people on top of one another. No ball playing, no pets, no noise, no frogs in your pockets— these places offer nothing that's normal for American kids.

Please tell me about the training program that you have for young people in archi- tectural drafting. It seems to me that al- though the products of architectural work are all around and influence everyone, you could live your whole life and never have to deal with an architect. It's as if they were invisible.

Especially if you are poor. This has been a dream of mine since Black kids in the cities were not Ellen White, Director of the Training Pro- gram, discussing work with a student. I thought that maybe cities would be better if more city youngsters were involved in design — but how could they aspire to something they knew noth- ing about?

They had no frame of reference for it. We had to create opportunities for them to learn. We get hard-core unem- ployed people who have no prior training; we teach architectural drafting, problem solving, office practices, codes, construc- tion. Therefore it is reasonable that I provide information on companies that offer products and services that help my listeners. The second reason I provide advertisement is to help pay for the costs of running this site and podcast.

That may not sound like a lot but to my wife, it is an expensive hobby. All advertisement is done as a personal endorsement. Currently I provide two types of advertisement. Paid advertisers also get mentions on the podcast. I also provide affiliate links which pay me per user purchase. I treat both the same. In addition, if you have a gardening product you would like me to try and review and are willing to send me a sample I will be glad to do so. I will provide at least a written review and mention it on the subsequent podcast.

I will also make every attempt to conduct a video review for products that warrant such things. Expect all reviews to be done with complete honesty — I work in QA during my day job — I will not sugar coat defects. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Josh rated it it was amazing Dec 19, Simon Campbell rated it it was ok Feb 21, Cheek rated it liked it Oct 02, David Kay rated it really liked it Jan 07, Vernon Hensley rated it liked it Jan 07, Allen Gilliard rated it liked it Sep 16, Andrew Lee Doyle rated it it was amazing Aug 10, Dustin Barney rated it really liked it Jan 28, William E Bradley rated it really liked it Dec 09, Robyn rated it really liked it May 29, Patrick rated it really liked it Feb 03, Dan rated it really liked it Aug 03, Macnicol rated it it was amazing Aug 06, Andrew Lee Doyle rated it really liked it Jan 29, Marie-Elaina B Larabee added it Dec 27, David Neal marked it as to-read Jan 03,