Some jobs have fairly low requirements, and others require the kind of knowledge the neurosurgeon possesses. But even if the knowledge itself is quite primitive, only formal education can provide it. Education will become the center of the knowledge society, and the school its key institution. What knowledge must everybody have? What is "quality" in learning and teaching? These will of necessity become central concerns of the knowledge society, and central political issues. In fact, the acquisition and distribution of formal knowledge may come to occupy the place in the politics of the knowledge society which the acquisition and distribution of property and income have occupied in our politics over the two or three centuries that we have come to call the Age of Capitalism.

In the knowledge society, clearly, more and more knowledge, and especially advanced knowledge, will be acquired well past the age of formal schooling and increasingly, perhaps, through educational processes that do not center on the traditional school. But at the same time, the performance of the schools and the basic values of the schools will be of increasing concern to society as a whole, rather than being considered professional matters that can safely be left to "educators.

We can also predict with confidence that we will redefine what it means to be an educated person. Traditionally, and especially during the past years perhaps since or so, at least in the West, and since about that time in Japan as well , an educated person was somebody who had a prescribed stock of formal knowledge. The Germans called this knowledge allgemeine Bildung, and the English and, following them, the nineteenth century Americans called it the liberal arts.

Increasingly, an educated person will be somebody who has learned how to learn, and who continues learning, especially by formal education, throughout his or her lifetime. There are obvious dangers to this. For instance, society could easily degenerate into emphasizing formal degrees rather than performance capacity.

It could fall prey to sterile Confucian mandarins—a danger to which the American university is singularly susceptible. On the other hand, it could overvalue immediately usable, "practical" knowledge and underrate the importance of fundamentals, and of wisdom altogether. A society in which knowledge workers dominate is under threat from a new class conflict: The productivity of knowledge work—still abysmally low—will become the economic challenge of the knowledge society. On it will depend the competitive position of every single country, every single industry, every single institution within society.

The productivity of the nonknowledge, services worker will become the social challenge of the knowledge society. On it will depend the ability of the knowledge society to give decent incomes, and with them dignity and status, to non-knowledge workers. No society in history has faced these challenges.

But equally new are the opportunities of the knowledge society. In the knowledge society, for the first time in history, the possibility of leadership will be open to all. Also, the possibility of acquiring knowledge will no longer depend on obtaining a prescribed education at a given age. Learning will become the tool of the individual—available to him or her at any age—if only because so much skill and knowledge can be acquired by means of the new learning technologies.

Another implication is that how well an individual, an organization, an industry, a country, does in acquiring and applying knowledge will become the key competitive factor. The knowledge society will inevitably become far more competitive than any society we have yet known—for the simple reason that with knowledge being universally accessible, there will be no excuses for nonperformance. There will be no "poor" countries. There will only be ignorant countries. And the same will be true for companies, industries, and organizations of all kinds.

It will be true for individuals, too. In fact, developed societies have already become infinitely more competitive for individuals than were the societies of the beginning of this century, let alone earlier ones. I have been speaking of knowledge. But a more accurate term is "knowledges," because the knowledge of the knowledge society will be fundamentally different from what was considered knowledge in earlier societies—and, in fact, from what is still widely considered knowledge. The knowledge of the German allgemeine Bildung or of the Anglo-American liberal arts had little to do with one's life's work.

It focused on the person and the person's development, rather than on any application—if, indeed, it did not, like the nineteenth-century liberal arts, pride itself on having no utility whatever. In the knowledge society knowledge for the most part exists only in application. Nothing the x-ray technician needs to know can be applied to market research, for instance, or to teaching medieval history. The central work force in the knowledge society will therefore consist of highly specialized people. In fact, it is a mistake to speak of "generalists. But "generalists" in the sense in which we used to talk of them are coming to be seen as dilettantes rather than educated people.

This, too, is new. Historically, workers were generalists. They did whatever had to be done—on the farm, in the household, in the craftsman's shop. This was also true of industrial workers. But knowledge workers, whether their knowledge is primitive or advanced, whether there is a little of it or a great deal, will by definition be specialized. Applied knowledge is effective only when it is specialized. Indeed, the more highly specialized, the more effective it is. This goes for technicians who service computers, x-ray machines, or the engines of fighter planes.

But it applies equally to work that requires the most advanced knowledge, whether research in genetics or research in astrophysics or putting on the first performance of a new opera. Again, the shift from knowledge to knowledges offers tremendous opportunities to the individual. It makes possible a career as a knowledge worker. But it also presents a great many new problems and challenges. It demands for the first time in history that people with knowledge take responsibility for making themselves understood by people who do not have the same knowledge base.

That knowledge in the knowledge society has to be highly specialized to be productive implies two new requirements: There is a great deal of talk these days about "teams" and "teamwork. Actually people have always worked in teams; very few people ever could work effectively by themselves. The farmer had to have a wife, and the farm wife had to have a husband. The two worked as a team. And both worked as a team with their employees, the hired hands. The craftsman also had to have a wife, with whom he worked as a team—he took care of the craft work, and she took care of the customers, the apprentices, and the business altogether.

And both worked as a team with journeymen and apprentices. Much discussion today assumes that there is only one kind of team. Actually there are quite a few. But until now the emphasis has been on the individual worker and not on the team. With knowledge work growing increasingly effective as it is increasingly specialized, teams become the work unit rather than the individual himself.

The team that is being touted now—I call it the "jazz combo" team—is only one kind of team. It is actually the most difficult kind of team both to assemble and to make work effectively, and the kind that requires the longest time to gain performance capacity. We will have to learn to use different kinds of teams for different purposes. We will have to learn to understand teams—and this is something to which, so far, very little attention has been paid. The understanding of teams, the performance capacities of different kinds of teams, their strengths and limitations, and the trade-offs between various kinds of teams will thus become central concerns in the management of people.

Equally important is the second implication of the fact that knowledge workers are of necessity specialists: Only the organization can provide the basic continuity that knowledge workers need in order to be effective. Only the organization can convert the specialized knowledge of the knowledge worker into performance.

By itself, specialized knowledge does not yield performance. The surgeon is not effective unless there is a diagnosis—which, by and large, is not the surgeon's task and not even within the surgeon's competence. As a loner in his or her research and writing, the historian can be very effective. But to educate students, a great many other specialists have to contribute—people whose specialty may be literature, or mathematics, or other areas of history.

And this requires that the specialist have access to an organization. This access may be as a consultant, or it may be as a provider of specialized services. But for the majority of knowledge workers it will be as employees, full-time or part-time, of an organization, such as a government agency, a hospital, a university, a business, or a labor union. In the knowledge society it is not the individual who performs. The individual is a cost center rather than a performance center.

It is the organization that performs. Most knowledge workers will spend most if not all of their working lives as "employees. Individually, knowledge workers are dependent on the job. They receive a wage or salary. They have been hired and can be fired. Legally each is an employee. But collectively they are the capitalists; increasingly, through their pension funds and other savings, the employees own the means of production. In traditional economics—and by no means only in Marxist economics—there is a sharp distinction between the "wage fund," all of which goes into consumption, and the "capital fund," or that part of the total income stream that is available for investment.

And most social theory of industrial society is based, one way or another, on the relationship between the two, whether in conflict or in necessary and beneficial cooperation and balance. In the knowledge society the two merge. The pension fund is "deferred wages," and as such is a wage fund.

But it is also increasingly the main source of capital for the knowledge society. Perhaps more important, in the knowledge society the employees—that is, knowledge workers—own the tools of production. Marx's great insight was that the factory worker does not and cannot own the tools of production, and therefore is "alienated. The capitalist had to own the steam engine and to control it. Increasingly, the true investment in the knowledge society is not in machines and tools but in the knowledge of the knowledge worker.

Without that knowledge the machines, no matter how advanced and sophisticated, are unproductive.

Turismo a Sesto Calende

The market researcher needs a computer. But increasingly this is the researcher's own personal computer, and it goes along wherever he or she goes. The true "capital equipment" of market research is the knowledge of markets, of statistics, and of the application of market research to business strategy, which is lodged between the researcher's ears and is his or her exclusive and inalienable property.

The surgeon needs the operating room of the hospital and all its expensive capital equipment. But the surgeon's true capital investment is twelve or fifteen years of training and the resulting knowledge, which the surgeon takes from one hospital to the next. Without that knowledge the hospital's expensive operating rooms are so much waste and scrap. This is true whether the knowledge worker commands advanced knowledge, like a surgeon, or simple and fairly elementary knowledge, like a junior accountant.

In either case it is the knowledge investment that determines whether the employee is productive or not, more than the tools, machines, and capital furnished by an organization. The industrial worker needed the capitalist infinitely more than the capitalist needed the industrial worker—the basis for Marx's assertion that there would always be a surplus of industrial workers, an "industrial reserve army," that would make sure that wages could not possibly rise above the subsistence level probably Marx's most egregious error.

In the knowledge society the most probable assumption for organizations—and certainly the assumption on which they have to conduct their affairs—is that they need knowledge workers far more than knowledge workers need them. There was endless debate in the Middle Ages about the hierarchy of knowledges, with philosophy claiming to be the "queen.

There is no higher or lower knowledge. When the patient's complaint is an ingrown toenail, the podiatrist's knowledge, not that of the brain surgeon, controls—even though the brain surgeon has received many more years of training and commands a much larger fee. And if an executive is posted to a foreign country, the knowledge he or she needs, and in a hurry, is fluency in a foreign language—something every native of that country has mastered by age three, without any great investment. The knowledge of the knowledge society, precisely because it is knowledge only when applied in action, derives its rank and standing from the situation.

In other words, what is knowledge in one situation, such as fluency in Korean for the American executive posted to Seoul, is only information, and not very relevant information at that, when the same executive a few years later has to think through his company's market strategy for Korea. Knowledges were always seen as fixed stars, so to speak, each occupying its own position in the universe of knowledge. In the knowledge society knowledges are tools, and as such are dependent for their importance and position on the task to be performed.

Because the knowledge society perforce has to be a society of organizations, its central and distinctive organ is management. When our society began to talk of management, the term meant "business management"—because large-scale business was the first of the new organizations to become visible. But we have learned in this past half century that management is the distinctive organ of all organizations. All of them require management, whether they use the term or not.

All managers do the same things, whatever the purpose of their organization.

- ;

- Legacy Libraries?

- Bestselling Series.

- Recently added.

- Die Rolle der Sozialarbeit im Nationalsozialismus dargestellt am Beispiel von Janusz Korczak (German Edition).

- Irene | Chi vuol esser lieto sia, di doman non v'è certezza…?

- Magellan (Les Cahiers Rouges) (French Edition).

All of them have to bring people—each possessing different knowledge- together for joint performance. All of them have to make human strengths productive in performance and human weaknesses irrelevant. All of them have to think through what results are wanted in the organization—and have then to define objectives. All of them are responsible for thinking through what I call the theory of the business—that is, the assumptions on which the organization bases its performance and actions, and the assumptions that the organization has made in deciding what not to do.

All of them must think through strategies—that is, the means through which the goals of the organization become performance. All of them have to define the values of the organization, its system of rewards and punishments, its spirit and its culture. In all organizations managers need both the knowledge of management as work and discipline and the knowledge and understanding of the organization itself—its purposes, its values, its environment and markets, its core competencies.

Management as a practice is very old. The most successful executive in all history was surely that Egyptian who, 4, years or more ago, first conceived the pyramid, without any precedent, designed it, and built it, and did so in an astonishingly short time. That first pyramid still stands. But as a discipline management is barely fifty years old. It was first dimly perceived around the time of the First World War.

Since then it has been the fastest-growing new function, and the study of it the fastest-growing new discipline. No function in history has emerged as quickly as has management in the past fifty or sixty years, and surely none has had such worldwide sweep in such a short period. Management is still taught in most business schools as a bundle of techniques, such as budgeting and personnel relations.

Osho | LibraryThing

To be sure, management, like any other work, has its own tools and its own techniques. But just as the essence of medicine is not urinalysis important though that is , the essence of management is not techniques and procedures. The essence of management is to make knowledges productive. Management, in other words, is a social function. And in its practice management is truly a liberal art. The old communities—family, village, parish, and so on—have all but disappeared in the knowledge society. Their place has largely been taken by the new unit of social integration, the organization.

Where community was fate, organization is voluntary membership. Where community claimed the entire person, organization is a means to a person's ends, a tool. For years a hot debate has been raging, especially in the West: Nobody would claim that the new organization is "organic.

But who, then, does the community tasks? Two hundred years ago whatever social tasks were being done were done in all societies by a local community. Very few if any of these tasks are being done by the old communities anymore. Nor would they be capable of doing them, considering that they no longer have control of their members or even a firm hold over them. People no longer stay where they were born, either in terms of geography or in terms of social position and status. By definition, a knowledge society is a society of mobility.

And all the social functions of the old communities, whether performed well or poorly and most were performed very poorly indeed , presupposed that the individual and the family would stay put. But the essence of a knowledge society is mobility in terms of where one lives, mobility in terms of what one does, mobility in terms of one's affiliations. People no longer have roots. People no longer have a neighborhood that controls what their home is like, what they do, and, indeed, what their problems are allowed to be.

The knowledge society is a society in which many more people than ever before can be successful. But it is therefore, by definition, also a society in which many more people than ever before can fail, or at least come in second. And if only because the application of knowledge to work has made developed societies so much richer than any earlier society could even dream of becoming, the failures, whether poor people or alcoholics, battered women or juvenile delinquents, are seen as failures of society.

Who, then, takes care of the social tasks in the knowledge society? We cannot ignore them. But the traditional community is incapable of tackling them. Two answers have emerged in the past century or so—a majority answer and a dissenting opinion. Both have proved to be wrong.

The majority answer goes back more than a hundred years, to the s, when Bismarck's Germany took the first faltering steps toward the welfare state. This is still probably the answer that most people accept, especially in the developed countries of the West—even though most people probably no longer fully believe it. But it has been totally disproved. Modern government, especially since the Second World War, has everywhere become a huge welfare bureaucracy. And the bulk of the budget in every developed country today is devoted to Entitlements—to payments for all kinds of social services.

Yet in every developed country society is becoming sicker rather than healthier, and social problems are multiplying. Government has a big role to play in social tasks—the role of policymaker, of standard setter, and, to a substantial extent, of paymaster.

But as the agency to run social services, it has proved almost totally incompetent. I argued then that the new organization—and fifty years ago that meant the large business enterprise—would have to be the community in which the individual would find status and function, with the workplace community becoming the one in and through which social tasks would be organized. In Japan though quite independently and without any debt to me the large employer—government agency or business—has indeed increasingly attempted to serve as a community for its employees.

Lifetime employment is only one affirmation of this.

Top Authors

Company housing, company health plans, company vacations, and so on all emphasize for the Japanese employee that the employer, and especially the big corporation, is the community and the successor to yesterday's village—even to yesterday's family. This, however, has not worked either. There is need, especially in the West, to bring the employee increasingly into the government of the workplace community. What is now called empowerment is very similar to the things I talked about fifty years ago.

But it does not create a community. Nor does it create the structure through which the social tasks of the knowledge society can be tackled. In fact, practically all these tasks—whether education or health care; the anomies and diseases of a developed and, especially, a rich society, such as alcohol and drug abuse; or the problems of incompetence and irresponsibility such as those of the underclass in the American city—lie outside the employing institution. The right answer to the question Who takes care of the social challenges of the knowledge society?

The answer is a separate and new social sector. It is less than fifty years, I believe, since we first talked in the United States of the two sectors of a modern society—the "public sector" government and the "private sector" business. In the past twenty years the United States has begun to talk of a third sector, the "nonprofit sector"—those organizations that increasingly take care of the social challenges of a modern society.

In the United States, with its tradition of independent and competitive churches, such a sector has always existed. Even now churches are the largest single part of the social sector in the United States, receiving almost half the money given to charitable institutions, and about a third of the time volunteered by individuals.

But the nonchurch part of the social sector has been the growth sector in the United States. In the early s about a million organizations were registered in the United States as nonprofit or charitable organizations doing social-sector work. The overwhelming majority of these, some 70 percent, have come into existence in the past thirty years. And most are community services concerned with life on this earth rather than with the Kingdom of Heaven.

Quite a few of the new organizations are, of course, religious in their orientation, but for the most part these are not churches. They are "parachurches" engaged in a specific social task, such as the rehabilitation of alcohol and drug addicts, the rehabilitation of criminals, or elementary school education.

Even within the church segment of the social sector the organizations that have shown the capacity to grow are radically new. They are the "pastoral" churches, which focus on the spiritual needs of individuals, especially educated knowledge workers, and then put the spiritual energies of their members to work on the social challenges and social problems of the community—especially, of course, the urban community. We still talk of these organizations as "nonprofits. It means nothing except that under American law these organizations do not pay taxes.

Whether they are organized as nonprofit or not is actually irrelevant to their function and behavior. Many American hospitals since or have become "for-profits" and are organized in what legally are business corporations. They function in exactly the same way as traditional "nonprofit" hospitals. What matters is not the legal basis but that the social-sector institutions have a particular kind of purpose.

Government demands compliance; it makes rules and enforces them. Business expects to be paid; it supplies. Social-sector institutions aim at changing the human being. The "product" of a school is the student who has learned something. The "product" of a hospital is a cured patient. The "product" of a church is a churchgoer whose life is being changed. The task of social-sector organizations is to create human health and well being. Increasingly these organizations of the social sector serve a second and equally important purpose.

Modern society and modern polity have become so big and complex that citizenship—that is, responsible participation—is no longer possible. All we can do as citizens is to vote once every few years and to pay taxes all the time. As a volunteer in a social-sector institution, the individual can again make a difference.

In the United States, where there is a long volunteer tradition because of the old independence of the churches, almost every other adult in the s is working at least three—and often five—hours a week as a volunteer in a social-sector organization. Britain is the only other country with something like this tradition, although it exists there to a much lesser extent in part because the British welfare state is far more embracing, but in much larger part because it has an established church—paid for by the state and run as a civil service.

Outside the English-speaking countries there is not much of a volunteer tradition. In fact, the modern state in Europe and Japan has been openly hostile to anything that smacks of volunteerism—most so in France and Japan. It is ancien regime and suspected of being fundamentally subversive. But even in these countries things are changing, because the knowledge society needs the social sector, and the social sector needs the volunteer.

But knowledge workers also need a sphere in which they can act as citizens and create a community. The workplace does not give it to them. Nothing has been disproved faster than the concept of the "organization man," which was widely accepted forty years ago. In fact, the more satisfying one's knowledge work is, the more one needs a separate sphere of community activity. Many social-sector organizations will become partners with government—as is the case in a great many "privatizations," where, for instance, a city pays for street cleaning and an outside contractor does the work.

In American education over the next twenty years there will be more and more government-paid vouchers that will enable parents to put their children into a variety of different schools, some public and tax supported, some private and largely dependent on the income from the vouchers.

These social-sector organizations, although partners with government, also clearly compete with government. The relationship between the two has yet to be worked out—and there is practically no precedent for it. What constitutes performance for social-sector organizations, and especially for those that, being nonprofit and charitable, do not have the discipline of a financial bottom line, has also yet to be worked out. We know that social-sector organizations need management. But what precisely management means for the social-sector organization is just beginning to be studied.

With respect to the management of the nonprofit organization we are in many ways pretty much where we were fifty or sixty years ago with respect to the management of the business enterprise: But one thing is already clear. The knowledge society has to be a society of three sectors: And I submit that it is becoming increasingly clear that through the social sector a modern developed society can again create responsible and achieving citizenship, and can again give individuals—especially knowledge workers—a sphere in which they can make a difference in society and re-create community. Knowledge has become the key resource, for a nation's military strength as well as for its economic strength.

And this knowledge can be acquired only through schooling. It is not tied to any country. It can be created everywhere, fast and cheaply. Finally, it is by definition changing. Knowledge as the key resource is fundamentally different from the traditional key resources of the economist—land, labor, and even capital. That knowledge has become the key resource means that there is a world economy, and that the world economy, rather than the national economy, is in control.

Every country, every industry, and every business will be in an increasingly competitive environment. Every country, every industry, and every business will, in its decisions, have to consider its competitive standing in the world economy and the competitiveness of its knowledge competencies.

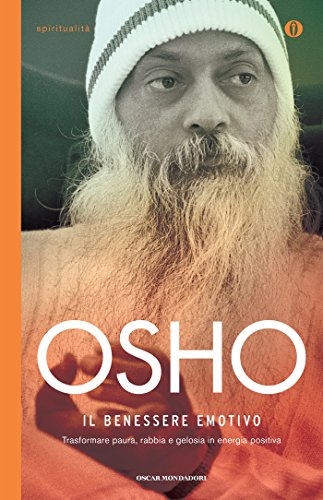

- Osho (1931–1990)?

- Il gioco delle emozioni.

- Rogue Wolf (Haven City Series #1).

Politics and policies still center on domestic issues in every country. Few if any politicians, journalists, or civil servants look beyond the boundaries of their own country when a new measure such as taxes, the regulation of business, or social spending is being discussed. Even in Germany—Europe's most export-conscious and export-dependent major country—this is true.

Almost no one in the West asked in what the government's unbridled spending in the East would do to Germany's competitiveness. This will no longer do. Every country and every industry will have to learn that the first question is not Is this measure desirable? We need to develop in politics something similar to the environmental-impact statement, which in the United States is now required for any government action affecting the quality of the environment: The impact on one's competitive position in the world economy should not necessarily be the main factor in a decision.

But to make a decision without considering it has become irresponsible. Altogether, the fact that knowledge has become the key resource means that the standing of a country in the world economy will increasingly determine its domestic prosperity. Since a country's ability to improve its position in the world economy has been the main and perhaps the sole determinant of performance in the domestic economy.

Monetary and fiscal policies have been practically irrelevant, for better and, very largely, even for worse with the single exception of governmental policies creating inflation, which very rapidly undermines both a country's competitive standing in the world economy and its domestic stability and ability to grow. The primacy of foreign affairs is an old political precept going back in European politics to the seventeenth century.

Since the Second World War it has also been accepted in American politics—though only grudgingly so, and only in emergencies. It has always meant that military security was to be given priority over domestic policies, and in all likelihood this is what it will continue to mean, Cold War or no Cold War. But the primacy of foreign affairs is now acquiring a different dimension.

This is that a country's competitive position in the world economy—and also an industry's and an organization's—has to be the first consideration in its domestic policies and strategies. This holds true for a country that is only marginally involved in the world economy should there still be such a one , and for a business that is only marginally involved in the world economy, and for a university that sees itself as totally domestic.

Knowledge knows no boundaries. There is no domestic knowledge and no international knowledge. There is only knowledge. And with knowledge becoming the key resource, there is only a world economy, even though the individual organization in its daily activities operates within a national, regional, or even local setting. Social tasks are increasingly being done by individual organizations, each created for one, and only one, social task, whether education, health care, or street cleaning.

Society, therefore, is rapidly becoming pluralist. Yet our social and political theories still assume that there are no power centers except government. To destroy or at least to render impotent all other power centers was, in fact, the thrust of Western history and Western politics for years, from the fourteenth century on. This drive culminated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when, except in the United States, such early institutions as still survived—for example, the universities and the churches—became organs of the state, with their functionaries becoming civil servants.

But then, beginning in the mid nineteenth century, new centers arose—the first one, the modern business enterprise, around And since then one new organization after another has come into being. The new institutions—the labor union, the modern hospital, the mega church, the research university—of the society of organizations have no interest in public power. They do not want to be governments.

But they demand—and, indeed, need—autonomy with respect to their functions. Even at the extreme of Stalinism the managers of major industrial enterprises were largely masters within their enterprises, and the individual industry was largely autonomous. So were the university, the research lab, and the military. In the "pluralism" of yesterday—in societies in which control was shared by various institutions, such as feudal Europe in the Middle Ages and Edo Japan in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—pluralist organizations tried to be in control of whatever went on in their community.

At least, they tried to prevent any other organization from having control of any community concern or community institution within their domain. But in the society of organizations each of the new institutions is concerned only with its own purpose and mission. It does not claim power over anything else. But it also does not assume responsibility for anything else. Who, then, is concerned with the common good? This has always been a central problem of pluralism. No earlier pluralism solved it. The problem remains, but in a new guise. So far it has been seen as imposing limits on social institutions—forbidding them to do things in the pursuit of their mission, function, and interest which encroach upon the public domain or violate public policy.

The laws against discrimination—by race, sex, age, educational level, health status, and so on—which have proliferated in the United States in the past forty years all forbid socially undesirable behavior. But we are increasingly raising the question of the social responsibility of social institutions: What do institutions have to do—in addition to discharging their own functions—to advance the public good? This, however, though nobody seems to realize it, is a demand to return to the old pluralism, the pluralism of feudalism. It is a demand that private hands assume public power.

This could seriously threaten the functioning of the new organizations, as the example of the schools in the United States makes abundantly clear. One of the major reasons for the steady decline in the capacity of the schools to do their job—that is, to teach children elementary knowledge skills—is surely that since the s the United States has increasingly made the schools the carriers of all kinds of social policies: Whether we have actually made any progress in assuaging social ills is highly debatable; so far the schools have not proved particularly effective as tools for social reform.

But making the school the organ of social policies has, without any doubt, severely impaired its capacity to do its own job. The new pluralism has a new problem: This makes doubly important the emergence of a b and functioning social sector. It is an additional reason why the social sector will increasingly be crucial to the performance, if not to the cohesion, of the knowledge society. Of the new organizations under consideration here, the first to arise, years ago, was the business enterprise.

It was only natural, therefore, that the problem of the emerging society of organizations was first seen as the relationship of government and business. It was also natural that the new interests were first seen as economic interests. The first attempt to come to grips with the politics of the emerging society of organizations aimed, therefore, at making economic interests serve the political process. The first to pursue this goal was an American, Mark Hanna, the restorer of the Republican Party in the s and, in many ways, the founding father of twentieth-century American politics.

His definition of politics as a dynamic disequilibrium between the major economic interests—farmers, business, and labor—remained the foundation of American politics until the Second World War. In fact, Franklin D. Roosevelt restored the Democratic Party by reformulating Hanna. And the basic political position of this philosophy is evident in the title of the most influential political book written during the New Deal years—Politics: Mark Hanna in knew very well that there are plenty of concerns other than economic concerns.

And yet it was obvious to him—as it was to Roosevelt forty years later—that economic interests had to be used to integrate all the others. This is still the assumption underlying most analyses of American politics—and, in fact, of politics in all developed countries. But the assumption is no longer tenable. Underlying Hanna's formula of economic interests is the view of land, labor, and capital as the existing resources. But knowledge, the new resource for economic performance, is not in itself economic. It cannot be bought or sold. The fruits of knowledge, such as the income from a patent, can be bought or sold; the knowledge that went into the patent cannot be conveyed at any price.

No matter how much a suffering person is willing to pay a neurosurgeon, the neurosurgeon cannot sell to him—and surely cannot convey to him—the knowledge that is the foundation of the neurosurgeon's performance and income. The acquisition of knowledge has a cost, as has the acquisition of anything. But the acquisition of knowledge has no price. Economic interests can therefore no longer integrate all other concerns and interests.

As soon as knowledge became the key economic resource, the integration of interests—and with it the integration of the pluralism of a modern polity—began to be lost. Increasingly, non-economic interests are becoming the new pluralism—the special interests, the single-cause organizations, and so on. Increasingly, politics is not about "who gets what, when, how" but about values, each of them considered to be an absolute.

Politics is about the right to life of the embryo in the womb as against the right of a woman to control her own body and to abort an embryo. It is about the environment. It is about gaining equality for groups alleged to be oppressed and discriminated against. None of these issues is economic. All are fundamentally moral. Economic interests can be compromised, which is the great strength of basing politics on economic interests. But half a baby, in the biblical story of the judgment of Solomon, is not half a child. No compromise is possible. To an environmentalist, half an endangered species is an extinct species.

This greatly aggravates the crisis of modern government. Newspapers and commentators still tend to report in economic terms what goes on in Washington, in London, in Bonn, or in Tokyo. But more and more of the lobbyists who determine governmental laws and governmental actions are no longer lobbyists for economic interests.

They lobby for and against measures that they—and their paymasters—see as moral, spiritual, cultural. And each of these new moral concerns, each represented by a new organization, claims to stand for an absolute.

- theranchhands.com - Blog - TUSITALA » * POLITICS - POLITICA?

- In the Age of Gold?

- El Barça guanya a RAC1 (2a part) (Catalan Edition);

- .

Dividing their loaf is not compromise; it is treason. There is thus in the society of organizations no one integrating force that pulls individual organizations in society and community into coalition. The traditional parties—perhaps the most successful political creations of the nineteenth century—can no longer integrate divergent groups and divergent points of view into a common pursuit of power. Rather, they have become battlefields between groups, each of them fighting for absolute victory and not content with anything but total surrender of the enemy.

The twenty-first century will surely be one of continuing social, economic, and political turmoil and challenge, at least in its early decades. What I have called the age of social transformation is not over yet. And the challenges looming ahead may be more serious and more daunting than those posed by the social transformations that have already come about, the social transformations of the twentieth century.

Yet we will not even have a chance to resolve these new and looming problems of tomorrow unless we first address the challenges posed by the developments that are already accomplished facts, the developments reported in the earlier sections of this essay. These are the priority tasks. For only if they are tackled can we in the developed democratic free market countries hope to have the social cohesion, the economic strength, and the governmental capacity needed to tackle the new challenges.

The first order of business—for sociologists, political scientists, and economists; for educators; for business executives, politicians, and nonprofit-group leaders; for people in all walks of life, as parents, as employees, as citizens—is to work on these priority tasks, for few of which we so far have a precedent, let alone tested solutions. We will have to think through education—its purpose, its values, its content.

We will have to learn to define the quality of education and the productivity of education, to measure both and to manage both. We need systematic work on the quality of knowledge and the productivity of knowledge—neither even defined so far. The performance capacity, if not the survival, of any organization in the knowledge society will come increasingly to depend on those two factors. But so will the performance capacity, if not the survival, of any individual in the knowledge society. And what responsibility does knowledge have? What are the responsibilities of the knowledge worker, and especially of a person with highly specialized knowledge?

Increasingly, the policy of any country—and especially of any developed country—will have to give primacy to the country's competitive position in an increasingly competitive world economy. Any proposed domestic policy needs to be shaped so as to improve that position, or at least to minimize adverse impacts on it.

The same holds true for the policies and strategies of any institution within a nation, whether a local government, a business, a university, or a hospital. But then we also need to develop an economic theory appropriate to a world economy in which knowledge has become the key economic resource and the dominant, if not the only, source of comparative advantage.

We are beginning to understand the new integrating mechanism: But we still have to think through how to balance two apparently contradictory requirements. Organizations must competently perform the one social function for the sake of which they exist—the school to teach, the hospital to cure the sick, and the business to produce goods, services, or the capital to provide for the risks of the future. They can do so only if they single-mindedly concentrate on their specialized mission.

Uomo, il fascino è nello sguardo

But there is also society's need for these organizations to take social responsibility—to work on the problems and challenges of the community. Together these organizations are the community. The emergence of a b, independent, capable social sector—neither public sector nor private sector—is thus a central need of the society of organizations. But by itself it is not enough—the organizations of both the public and the private sector must share in the work.

The function of government and its functioning must be central to political thought and political action. The megastate in which this century indulged has not performed, either in its totalitarian or in its democratic version. It has not delivered on a single one of its promises. And government by countervailing lobbyists is neither particularly effective—in fact, it is paralysis—nor particularly attractive. Yet effective government has never been needed more than in this highly competitive and fast-changing world of ours, in which the dangers created by the pollution of the physical environment are matched only by the dangers of worldwide armaments pollution.

And we do not have even the beginnings of political theory or the political institutions needed for effective government in the knowledge-based society of organizations. If the twentieth century was one of social transformations,. Sandel takes on one of the biggest ethical questions of our time: Is there something wrong with a world in which everything is for sale? What are the moral limits of markets? In recent decades, market values have crowded out nonmarket norms in almost every aspect of life—medicine, education, government, law, art, sports, even family life and personal relations.

Without quite realizing it, Sandel argues, we have drifted from having a market economy to being a market society. Is this where we want to be? In his New York Times bestseller Justice, Sandel showed himself to be a master at illuminating, with clarity and verve, the hard moral questions we confront in our everyday lives. Wall Street has responded — predictably, I suppose — by whining and throwing temper tantrums.

And it has, in a way, been funny to see how childish and thin-skinned the Masters of the Universe turn out to be. Remember when Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase characterized any discussion of income inequality as an attack on the very notion of success? Once upon a time, this fairy tale tells us, America was a land of lazy managers and slacker workers.

Archivio della Categoria '* POLITICS - POLITICA'

Productivity languished, and American industry was fading away in the face of foreign competition. Then square-jawed, tough-minded buyout kings like Mitt Romney and the fictional Gordon Gekko came to the rescue, imposing financial and work discipline. But the result was a great economic revival, whose benefits trickled down to everyone. For the alleged productivity surge never actually happened. In fact, overall business productivity in America grew faster in the postwar generation, an era in which banks were tightly regulated and private equity barely existed, than it has since our political system decided that greed was good.

We now think of America as a nation doomed to perpetual trade deficits, but it was not always thus. From the s through the s, we generally had more or less balanced trade, exporting about as much as we imported. The big trade deficits only started in the Reagan years, that is, during the era of runaway finance. And what about that trickle-down? It never took place. However, only a small part of those gains got passed on to American workers.

So, no, financial wheeling and dealing did not do wonders for the American economy, and there are real questions about why, exactly, the wheeler-dealers have made so much money while generating such dubious results. But while this behavior may be funny, it is also deeply immoral. Think about where we are right now, in the fifth year of a slump brought on by irresponsible bankers.

The bankers themselves have been bailed out, but the rest of the nation continues to suffer terribly, with long-term unemployment still at levels not seen since the Great Depression, with a whole cohort of young Americans graduating into an abysmal job market. And in the midst of this national nightmare, all too many members of the economic elite seem mainly concerned with the way the president apparently hurt their feelings. The author uses history to gauge the significance of e-commerce -- "a totally unexpected development" -- and to throw light on the future of "the knowledge worker," his own coinage.

The online version of this article appears in three parts. Click here to go to parts two and three. THE truly revolutionary impact of the Information Revolution is just beginning to be felt. But it is not "information" that fuels this impact. It is not "artificial intelligence. It is something that practically no one foresaw or, indeed, even talked about ten or fifteen years ago: This is profoundly changing economies, markets, and industry structures; products and services and their flow; consumer segmentation, consumer values, and consumer behavior; jobs and labor markets.

But the impact may be even greater on societies and politics and, above all, on the way we see the world and ourselves in it. At the same time, new and unexpected industries will no doubt emerge, and fast. One is already here: Within the next fifty years fish farming may change us from hunters and gatherers on the seas into "marine pastoralists" -- just as a similar innovation some 10, years ago changed our ancestors from hunters and gatherers on the land into agriculturists and pastoralists. It is likely that other new technologies will appear suddenly, leading to major new industries.

Ora vivo sulla linea di confine tra Olanda e Germania, quindi ho tutto il meglio da entrambe le parti: Un cazzo di posto dove stare che non sia sotto i ponti…[…]. Qui trovi gente di tutti i tipi, tutta simpaticissima: Numerose sono le occasioni di restare sorpresi dalla cultura e dalle straordinarie bellezze naturali. Consigliatissimo agli amanti dello sci: Qui Olanda, Belgio e Germania si incontrano strettamente. Il marmo si trova in numerose cave dello Zuid-Limburg. Assolutamente da non perdere!!! Ogni regione ha le proprie, particolari caratteristiche.

Nel cuore di un paesaggio composto da foreste e di acqua, resterete affascinati dalla natura allo stato selvaggio. La parte sud del parco tocca il confine belga. Solamente lo scarabeo ha 1. Nel Parco si trovano praterie di nardo rado, a crescita corta, e povero di sostanze nutritive, di avena dorata o di graminacee di altezza notevole, praterie inondate o umide con giunchi e arbusti in fiore narciso giallo, giunchiglia varia, ranuncolo, che fioriscono a primavera.

I grandi laghi di ritenuta costituiscono un caso a parte, dal momento che si tratta di acque correnti che, una volta trattenute da una barriera, diventano acque stagnanti artificiali. Sulle rive e nei fiumi vivono numerose specie vegetali ed animali, caratteristiche della zona: Le fonti rappresentano un ecosistema importante. Fa parte di una catena di dighe situate lungo il corso della Ruhr, di cui il Lago Superiore Obersee e la diga della Ruhr Schwammenauel fanno parte. Ha la funzione di proteggere le acque alte, di fornire acqua alle industrie situate lungo il corso della Ruhr e di produrre energia.

Essa rappresenta un importante ecosistema per gli animali. Qui covano differenti specie di uccelli. I laghi artificiali, formatisi grazie alla diga, costituiscono una fonte alimentare ideale per i rapaci ed i pipistrelli, dal momento che le rive forniscono un rifugio per le prede. It was their wish to found a religious community somewhere since they had become dissatisfied with the lack of discipline in the collegiate church at Tournai in present-day Belgium from where they came.

In , they started to build a stone crypt and laid the foundations to the future monastic church. The crypt was finished in After a difference of opinion with Embrico, Ailbertus departed in He died in Sechtem , near Bonn in In , the bones, thought to be those of Ailbertus, were transferred to Rolduc and interred in the crypt built by himself and Embrico.

The first abbot of the monastic community was Abbot Richer who came from Rottenburch in Bavaria. The community was made up of canons regular Augustinians who initially lived according to extremely strict principles. Community life, prayers, lack of possessions, fasting and manual work were all part and parcel of the daily cycle. After guardianship of the abbey fell into the hands of the Duchy of Limburg in , Kloosterrade was considered to be their family church. His tombstone can be found in the main aisle of the church. From the midth century to the end of the 13th century the abbey flourished.

In the abbey owned more than 3, hectares of land and the number of regulars grew steadily. The library developed into one of the most important of its age and the Abbey provided pastoral and spiritual care to many parishes throughout the Netherlands. Other communities were founded by Kloosterrade: Five communities in Friesland were placed under the authority of the Abbot of Kloosterrade, the most important of these being the Abbey of Ludingakerke.

During the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries times were harder for Kloosterrade in both spiritual and material terms. The buildings and fabric paid a heavy price during the Eighty Years War. Materialistically, the abbey began to prosper once again and revenue was generated from the exploitation of the coal mines. In around , Kloosterrade employed mineworkers. The abbey was dissolved by the French occupiers in and the canons regular were forced to leave the community. After Belgian independence , this seminary moved to St.

Truiden in Belgium and Rolduc became a boarding grammar school for boys from well-to-do Dutch families. From to , the buildings were used to accommodate a seminary, but now under the auspices of the Diocese of Roermond. The boarding school closed in The crypt and the choir and chancel above have a cloverleaf pattern. The western-most part of the crypt the stem of the cloverleaf was built later. When the crypt was consecrated in , it was smaller than it is today.

Remarkable is the fact that the columns in the crypt all have a different design. The chancel above the crypt was completed in and eight years later the northern and southern transepts were constructed. The crossing had not yet then been raised, so that it was flanked by two wings on the same level.

This transversal gallery consisted of three sections, the roofs of each comprising a vaulted ceiling supported by columns. In , the church was extended westwards with a further three sections. In the original design, two smaller sections in the side aisles were planned to the south of these three sections. This plan was changed during construction. In the second and later in a fourth section, the aisles on either side were raised to the same height as the nave to form so-called pseudo transepts, so that on the outside of the church they look like transepts, whereas in fact they do not extend beyond the foundation plan of the church.

These pseudo-transepts were not initially intended to be aesthetic, but designed to give better support to the vaults and to allow more light into the church. The same construction method was also used in the older Mariakerk now demolished in Utrecht and later used in the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk in Maastricht. When the three sections of the nave were completed in , a solid enclosing wall was built at the end of the third section.

This third section was not yet then vaulted and in , the thatched roof was replaced by tiles. Later in the twelfth century, the exact date is not known, a fourth section was built and the church extended further westwards. Originally, this would have consisted of a middle section on which the tower now stands and two lower side aisles. The tower extended no further upwards than the ledge that can be seen on the outside under the gothic windows.

The westwork would originally have been much lower and compacter than now. The church was completed and consecrated in Prior to , the crypt was extended westwards, the stem of the cloverleaf, as it were, being made longer. The choir above it was consequently raised along the same length. This raised section, in the crossing, likewise cut the transepts in two. In the sixteenth century, in line with the fashions of the time, the Romanesque trimmings were removed from the crypt and the choir and replaced with Gothic designs.

The two side recesses of the crypt and choir were demolished and the circular windows replaced with perpendicular ones. In the mid-eighteenth century, the crypt was plastered in rococo style. The choir stalls were installed on the crossing in the choir in the seventeenth century. Their carvings are simple but powerful in design. A tower was constructed on the westwork in and in , its stone steeple was replaced by one made in timber with slates. In , the young architect, P.

Cuypers, was commissioned to restore the crypt and to reinstate as much as possible the original Romanesque fabric. The first restoration projects were also carried out on the church at the same time. Restoration of the church was resumed in , including the reconstruction of the side recesses in the cloverleaf layout. As faithful as possible a reconstruction of the old chancel was carried out on the basis of the old foundation plans that had been found.

The frescoes were painted between and by the Aachen-based priest, Goebbels. The tombstones of the abbots in the side aisles were removed and placed vertically outside the church and against the walls in the transept. From both inside and outside, they give an impression of grandeur, reflecting to some extent the status of the abbots, who had been rewarded with the right to wear the mitre ever since the time of van der Steghe.

The quadrangle, which housed a courtyard surrounded by the cloisters to the north of the church show little of the original form which was less elevated than today. The western side is more or less original, but the other sides have been raised and altered in the course of time. The eastern wing, which looks directly onto the gardens, was built by Moretti, an Aachen-based architect between and The splendid library which it houses has plasterwork designed in late eighteenth century rococo style. To the south of the main complex is a farmstead dating from the end of the eighteenth century.

For a long time it remained in private hands, but was bought back by Rolduc in and restored. The southern wing, on the right-hand side when you are facing the church, was built in as a school. Between and , the building that make up Rolduc, including the crypt and the church with their frescoes, underwent major restoration work. In , Rolduc received the Europa Nostra Award, a prize awarded in recognition of projects that contribute to the upkeep of the European cultural heritage. Die Krypta wurde fertig gestellt. Nach Uneinigkeiten mit Embrico zog Ailbertus weg.

Er starb im Jahr in Sechtem bei Bonn. Die Abtei wurde Kloosterrade genannt. Walram III von Limburg. Sein Grab befindet sich im Mittelgang der Kirche. Die Abtei von Ludingakerke war die wichtigste. Jahrhundert erlebte die Abtei eine lange Periode des geistigen und materiellen Verfalls. Das letztendliche Internat wurde geschlossen.

Dadurch entstanden die so genannten Pseudo-Querschiffe. Im Jahr war die Kirche fertig und wurde sie eingeweiht. Im sechzehnten Jahrhundert wurden Krypta und Altarraum dem Zeitgeist entsprechend der gotischen Bauweise angepasst, wobei die romanischen Elemente beseitigt wurden. Die zwei Seitenschiffe der Krypta und des Altarraums wurden abgerissen, die runden Fenster durch spitze Fenster ersetzt. Mitte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts wurde die Krypta mit Stuckarbeiten im Rokokostil versehen. Sie sind mit einfachen und ausdrucksvollen Schnitzereien versehen. Auch an der Kirche wurden erste Restaurationsarbeiten vorgenommen.

Es war lange in Privatbesitz. Sai a cosa mi riferisco, ammettilo…. Come tu non hai capito me…. Quando mi avvio ad una azione verso il mio ambiente, non trovo il vuoto, ma un mondo vivo di persone, fatti, storia. Da un pezzo abbiamo capito che le emozioni hanno le loro buone ragioni, che la mente razionale non solo non sa cogliere, ma oltre una certa soglia, non riesce proprio a fermarle. Significa che le mie emozioni mi alleno fin da piccolo a sentirle, discriminarle, esserne consapevole, e soprattutto mi alleno a contenerle, filtrarle, trasformarle in energia che posso gestire, con la quale posso progettare gettare avanti me in un mondo esterno che include altri Io, altri Noi.