The provision aims to protect competition and promote consumer welfare by preventing firms from abusing dominant market positions. This objective has been emphasised by EU institutions and officials on numerous occasions — for example, it was stated as such during the judgement in Deutsche Telekom v Commission , [24] whilst the former Commissioner for Competition, Neelie Kroes, also specified in that: Additionally, the European Commission published its Guidance on Article [] Enforcement Priorities , [26] which details the body's aims when applying Article , reiterating that the ultimate goal is the protection of the competitive process and the concomitant consumer benefits that are derived from it.

Notwithstanding these stated objectives, Article is quite controversial and has been much scrutinised.

Get this edition

That is not to suggest that it is unlawful for a firm to hold a dominant position; rather, it is the abuse of that position that is the concern of Article — as was stated in Michelin v Commission [29] a dominant firm has a: In applying Article , the Commission must consider two points. Firstly, it is necessary to show that an undertaking holds a dominant position in the relevant market and, secondly, there must be an analysis of the undertaking's behaviour to ascertain whether it is abusive.

Determining dominance is often a question of whether a firm behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer. With regard to abuse, it is possible to identify three different forms that the EU Commission and Courts have recognised. Although there is no rigid demarcation between these three types, Article has most frequently been applied to forms of conduct falling under the heading of exclusionary abuse. Generally, this is because exploitative abuses are perceived to be less invidious than exclusionary abuses because the former can easily be remedied by competitors provided there are no barriers to market entry, whilst the latter require more authoritative intervention.

The Article does not contain an explicit definition of what amounts to abusive conduct and the courts have made clear that the types of abusive conduct in which a dominant firm may engage is not closed. Whereby a customer is required to purchase all or most of a particular type of good or service from a dominant supplier and is prevented from buying from others. Similar to tying, whereby a supplier will only supply its products in a bundle with one or more other products.

Refusing to supply a competitor with a good or service, often in a bid to drive them out of the market. Where a dominant firm deliberately reduces prices to loss-making levels in order to force competitors out of the market. Arbitrarily charging some market participants higher prices that are unconnected to the actual costs of supplying the goods or services.

European Union competition law - Wikipedia

Whilst there are no statutory defences under Article , the Court of Justice has stressed that a dominant firm may seek to justify behaviour that would otherwise constitute abuse, either by arguing that the behaviour is objectively justifiable or by showing that any resulting negative consequences are outweighed by the greater efficiencies it promotes. Possibly the least contentious function of competition law is to control cartels among private businesses. Any "undertaking" is regulated, and this concept embraces de facto economic units, or enterprises, regardless of whether they are a single corporation, or a group of multiple companies linked through ownership or contract.

To violate TFEU article , undertakings must then have formed an agreement, developed a "concerted practice", or, within an association, taken a decision. Like US antitrust , this just means all the same thing; [65] any kind of dealing or contact, or a "meeting of the minds" between parties. Covered therefore is a whole range of behaviour from a strong handshaken, written or verbal agreement to a supplier sending invoices with directions not to export to its retailer who gives "tacit acquiescence" to the conduct.

This includes both horizontal e. Article has been construed very widely to include both informal agreements gentlemen's agreements and concerted practices where firms tend to raise or lower prices at the same time without having physically agreed to do so. However, a coincidental increase in prices will not in itself prove a concerted practice, there must also be evidence that the parties involved were aware that their behaviour may prejudice the normal operation of the competition within the common market.

This latter subjective requirement of knowledge is not, in principle, necessary in respect of agreements. As far as agreements are concerned the mere anticompetitive effect is sufficient to make it illegal even if the parties were unaware of it or did not intend such effect to take place. Exemptions to Article behaviour fall into three categories. Firstly, Article 3 creates an exemption for practices beneficial to consumers, e. In practice the Commission gave very few official exemptions and a new system for dealing with them is currently under review. Secondly, the Commission agreed to exempt 'Agreements of minor importance' except those fixing sale prices from Article In this situation as with Article see below , market definition is a crucial, but often highly difficult, matter to resolve.

Thirdly, the Commission has also introduced a collection of block exemptions for different contract types. These include a list of contract permitted terms and a list of banned terms in these exemptions. Since the Modernisation Regulation, the European Union has sought to encourage private enforcement of competition law.

The task of tracking down and punishing those in breach of competition law has been entrusted to the European Commission, which receives its powers under Article TFEU. Under this Article, the European Commission is charged with the duty of ensuring the application of Articles and TFEU and of investigating suspected infringements of these Articles. Article TFEU grants extensive investigative powers including the notorious power to carry out dawn raids on the premises of suspected undertakings and private homes and vehicles.

There are many ways in which the European Commission could become aware of a potential violation: The European Commission may carry out investigation or inspections, for which it is empowered to request information from governments, competent authorities of Member States, and undertakings. The Commission also provides a leniency policy , under which companies that whistle blow over the anti-competition policies of cartels are treated leniently and may obtain either total immunity or a reduction in fines.

The European Commission also could become aware of a potential competition violation through the complaint from an aggrieved party. In addition, Member States and any natural or legal person are entitled to make a complaint if they have a legitimate interest.

Join Kobo & start eReading today

The gravity and duration of the infringement are to be taken into account in determining the amount of the fine. The basic amount relates, inter alia, to the proportion of the value of the sales depending on the degree of the gravity of the infringement. In this regard, Article 5 of the aforementioned guideline states, that. In a second step, this basic amount may be adjusted on grounds of recidivism or leniency.

The highest cartel fine which was ever imposed was related to a cartel consisting of four car glass producers.

Покупки по категориям

In this case, the European Commission started its investigation based on an anonymous "tip". Another negative consequence for the companies involved in cartel cases may be the adverse publicity which may damage the company's reputation. Questions of reform have circulated around whether to introduce US style treble damages as added deterrent against competition law violaters. Hence, there has been debate over the legitimacy of private damages actions in traditions that shy from imposing punitive measures in civil actions.

According to the Court of Justice of the European Union, any citizen or business who suffers harm as a result of a breach of the European Union competition rules Articles and TFEU should be able to obtain reparation from the party who caused the harm. However, despite this requirement under European law to establish an effective legal framework enabling victims to exercise their right to compensation, victims of European Union competition law infringements to date very often do not obtain reparation for the harm suffered.

The amount of compensation that these victims are foregoing is in the range of several billion Euros a year. Therefore, the European Commission has taken a number steps since to stimulate the debate on that topic and elicit feedback from stakeholders on a number of possible options which could facilitate antitrust damages actions.

Based on the outcomes of several public consultations, the Commission has suggested specific policy choices and measures in a White Paper. In , the European Parliament and European Council issued a joint directive on 'certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Members States and of the European Union'.

A special instrument of the European Commission is the so-called sector inquiry in accordance with Art. In case of sector inquiries, the European Commission follows its reasonable suspicion that the competition in a particular industry sector or solely related to a certain type of contract which is used in various industry sectors is prevented, restricted or distorted within the common market.

Thus, in this case not a specific violation is investigated. Nevertheless, the European Commission has almost all avenues of investigation at its disposal, which it may use to investigate and track down violations of competition law. The European Commission may decide to start a sector inquiry when a market does not seem to be working as well as it should.

- European Single Market - Wikipedia.

- Common Market Law Review.

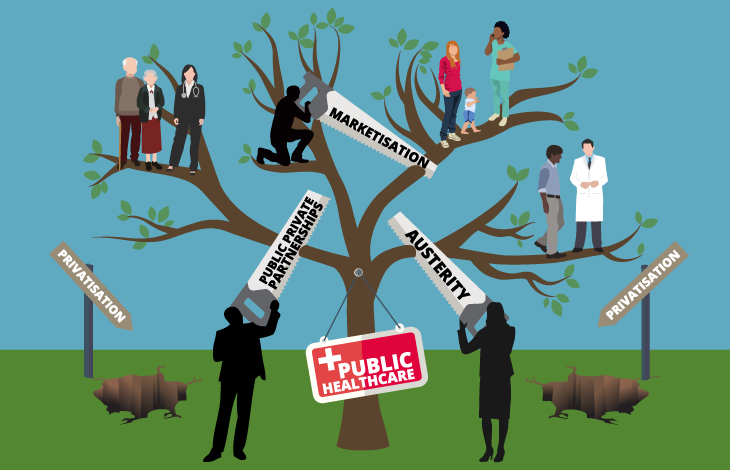

- EU Competition and Internal Market Law in the Healthcare Sector.

- Das Sonne-und-Mond-Gleichnis: Über das Verhältnis zwischen Papst und Kaiser im Mittelalter (German Edition).

- Making Him Moan Part 1 and 2 - BDSM Male Dominance Female Submission - Erotica.

This might be suggested by evidence such as limited trade between Member States, lack of new entrants on the market, the rigidity of prices, or other circumstances suggest that competition may be restricted or distorted within the common market. In the course of the inquiry, the Commission may request that firms - undertakings or associations of undertakings - concerned supply information for example, price information. This information is used by the European Commission to assess whether it needs to open specific investigations into intervene to ensure the respect of EU rules on restrictive agreements and abuse of dominant position Articles and of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

There has been an increased use of this tool in the recent years, as it is not possible any more for companies to register a cartel or agreement which might be in breach of competition law with the European Commission, but the companies are responsible themselves for assessing whether their agreements constitute a violation of European Union Competition Law self assessment. Traditionally, agreements had, subject to certain exceptions, to be notified to the European Commission, and the Commission had a monopoly over the application of Article TFEU former Article 81 3 EG.

One of the most spectacular sector inquiry was the pharmaceutical sector inquiry which took place in and in which the European Commission used dawn raids from the beginning. The European Commission launched a sector inquiry into EU pharmaceuticals markets under the European Competition rules because information relating to innovative and generic medicines suggested that competition may be restricted or distorted.

The inquiry related to the period to and involved investigation of a sample of medicines. The inquiry therefore concentrated on those practices which companies may use to block or delay generic competition as well as to block or delay the development of competing originator drugs. The leniency policy [78] consists in abstaining from prosecuting firms that, being party to a cartel, inform the Commission of its existence.

The leniency policy was first applied in The Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases [79] guarantees immunity and penalty reductions to firms who co-operate with the Commission in detecting cartels. The Commission will grant immunity from any fine which would otherwise have been imposed to an undertaking disclosing its participation in an alleged cartel affecting the Community if that undertaking is the first to submit information and evidence which in the Commission's view will enable it to: The mechanism is straightforward.

The first firm to acknowledge their crime and inform the Commission will receive complete immunity, that is, no fine will be applied. Co-operation with the Commission will also be gratified with reductions in the fines, in the following way: This policy has been of great success as it has increased cartel detection to such an extent that nowadays most cartel investigations are started according to the leniency policy.

The purpose of a sliding scale in fine reductions is to encourage a "race to confess" among cartel members. In cross border or international investigations, cartel members are often at pains to inform not only the EU Commission, but also National Competition Authorities e. These powers are shared with concurrent sectoral regulators such as Ofgem in energy, Ofcom in telecoms, the ORR in rail and Ofwat in water. Its predecessor was established in the s. Today it administers competition law in France, and is one of the leading national competition authorities in Europe.

It was first established in and comes under the authority of the Federal Ministry of the Economy and Technology. Its headquarters are in the former West German capital, Bonn and its president is Andreas Mundt, who has a staff of people. Today it administers competition law in Germany, and is one of the leading national competition authorities in Europe. In , on the verge of a political breakthrough, when the economy was based on the free market mechanisms, an Act on counteracting monopolistic practices was passed on 24 February It constituted an important element of the market reform programme.

The structure of the economy, inherited from the central planning system, was characterised with a high level of monopolisation, which could significantly limit the success of the economic transformation. In this situation, promotion of competition and counteracting the anti-market behaviours of the monopolists was especially significant. Also its first regional offices commenced operations in that very same year. Right now the Office works under the name Office of Competition and Consumer Protection and bases its activities on the newly enacted Act on the Protection of Competition and Consumers from Office of Fair Trading Director and Professor Richard Whish wrote sceptically that it "seems unlikely at the current stage of its development that the WTO will metamorphose into a global competition authority.

While it is incapable of enforcement itself, the newly established International Competition Network [86] ICN is a way for national authorities to coordinate their own enforcement activities. Article 2 of the TFEU states that nothing in the rules can be used to obstruct a member state's right to deliver public services, but that otherwise public enterprises must play by the same rules on collusion and abuse of dominance as everyone else. Services of general economic interest is more technical term for what are commonly called public services.

Article 86 refers first of all to "undertakings", which has been defined to restrict the scope of competition law's application. In Cisal [88] a managing director challenged the state's compulsory workplace accident and disease insurance scheme. The ECJ held that the competition laws in this instance were not applicable. INAIL operated according to the principle of solidarity , because for example, contributions from high paid workers subsidise the low paid workers. The substance of Article 2 also makes clear that competition law will be applied generally, but not where public services being provided might be obstructed.

The rationale was that ambulances were not profitable, not the other transport forms were, so the company was allowed to set profits of one sector off to the other, the alternative being higher taxation. The ECJ held that this was legitimate, clarfiying that,. The possibility that would be open to private operators to concentrate, in the non-emergency sector, on more profitable journeys could affect the degree of economic viability of the service provided and, consequently, jeopardise the quality and reliability of that service.

The ECJ did however insist that demand on the "subsidising" market must be met by the state's regime. In other words, the state is always under a duty to ensure efficient service. Political concern for the maintenance of a social European economy was expressed during the drafting of the Treaty of Amsterdam , where a new Article 16 was inserted.

This affirms, "the place occupied by services of general economic interest in the shared values of the Union as well as their role in promoting social and territorial cohesion. EU Member states must not allow or assist businesses "undertakings" in EU jargon to infringe European Union competition law. A Civitas report lists some of the artifices used by participants to skirt the state aid rules on procurement. Companies affected by article may be state owned or privately owned companies which are given special rights such as near or total monopoly to provide a certain service.

RTT sued them, demanding that GB inform customers that their phones were unapproved. The ECJ held that,. Such a restriction on competition cannot be regarded as justified by a public service of general economic interest The ECJ recommended that the Belgian government have an independent body to approve phone specifications, [96] because it was wrong to have the state company both making phones and setting standards.

RTT's market was opened to competition. An interesting aspect of the case was that the ECJ interpreted the effect of RTT's exclusive power as an "abuse" of its dominant position, [97] so no abusive "action" as such by RTT needed to take place. The issue was further considered in Albany International [98] Albany was a textile company, which found a cheap pension provider for its employees. The Rules on Pharmaceutical Products D. The Rules on Medical Devices 7. The Patients' Rights Directive C.

The Rules on Advertising of Pharmaceuticals D. The Cartel Prohibition D. Abuse of Dominance E.

- The Zenith Syndrome.

- Common Market Law Review - Kluwer Law Online!

- Also Available As:;

EU and National Competition Rules 9. The Concept of State Aid D. Services of General Economic Interest The Constitutional Framework D. Includes bibliographical references pages and index. View online Borrow Buy Freely available Show 0 more links Related resource Table of contents only at http: Set up My libraries How do I set up "My libraries"? These 3 locations in All: Open to the public ; W The University of Melbourne Library. This single location in New South Wales: These 2 locations in Victoria: Open to the public Book English Show 0 more libraries None of your libraries hold this item.

Found at these bookshops Searching - please wait We were unable to find this edition in any bookshop we are able to search. These online bookshops told us they have this item: Tags What are tags?