In vocal music, the instrumental accompaniment functions as a support for the poetry of the melody. French music, however, followed another trajectory; it bears another project. It falls under an alliance between the significant verb and the imaging sound. It is built upon a token of reciprocity between the rhetoric and the visual. Ferry argues that this doctrine of imitation, typical of the French Baroque, places the artists, in the broad definition of the word, in a position opposite to the one they will have in the following century, in the Romantic era: And if the principle of taste is reason, it is also very clear that genuine genius does not invent but rather discovers […].

For instance, the typical movements of the French suite such as the allemande, courante, etc. The tradition of the French suite and its dances sustained works for harpsichord well into the eighteenth century, the widespread knowledge of court dancing serving as a reference point for an educated audience. Couperin still wrote some dance movements, but introduced character pieces. He explained the nature of these works in the preface to his first book: I always had a subject while composing all these pieces: However, as among these titles some seem to favour myself, it would be advisable to point out that the pieces that bear them are like portraits that have sometimes been said to be quite evocative under my fingers, and that most of these flattering titles are given to the obliging originals that I wanted to represent, rather than to the copies I drew from them.

The nature, source, subjects, and type of imitation changed, but the concept itself still remained. This different type of imitation also demonstrates changes in the mentality of the time. In the early eighteenth century, when Couperin started publishing his harpsichord works, the days of court dancing the seventeenth century had known were past. The need for this type of music was slowly fading away as new values were being introduced into the minds of the Parisian nobility and higher classes, a movement that seems to have been reflected even in the evolution of keyboard forms.

Any art of imitation having its own particular hieroglyph, I wish that some educated and delicate mind would take it upon himself to compare them. But to gather the common charms of poetry, of painting, and of music, to show their analogies, to explain how a poet, a painter, and a musician deliver the same image, to grasp the fleeting emblems of their expression, to consider if there is not some similitude among these emblems, etc.

Do not fail either to include at the beginning of this work a chapter about what is this beautiful nature belle nature ; because I know of people who agree with me, that without one of these things your treatise remains without foundation, and that without the other, it lacks application. Teach them, sir, once and for all how each art imitates nature in one corresponding object; and show them that it is false that, as they claim, all nature is beautiful, and that the only ugly nature is the one that is not in its proper place.

He introduced an interesting concept that has intrigued scholars ever since. Many hypotheses have been proposed as to what this concept might have meant for Diderot. What emerges as a possible meaning is both startling and brilliant. Henry Le Gras, He seemed to have reached the point where traditional ideas on imitation and nature failed to explain why pure, instrumental music had such an effect on his soul, even if devoid of visual or poetic referents.

Painting shows the object itself, poetry describes it, music barely induces an idea. Music only has resources in the intervals and duration of sounds; and what analogy is there between this kind of sketch, and the spring, the darkness, the solitude, etc. How is it then that out of the three forms of art that imitate nature, the one of which the expression is the most arbitrary and the least precise is the one that speaks most strongly to the soul? Could it be that, in portraying objects less precisely, it leaves more room for our imagination; or that needing jolts to be moved, music is more able than painting and poetry to cause in us this tumultuous effect?

She adds that, in fact, he most probably did not have any influence on post-Revolutionary music, nor did Rousseau. This pure music did not relate directly to the concept of the imitation of the beautiful belle nature that was the basis of the French aesthetic of the time. How is it that this music, which has no objective meaning, is yet so attractive and pleasing to the soul and ear? Despite the fact that Diderot did not state it explicitly, it is evident in his writings that the understanding of musical expressivity in the mid-eighteenth century was changing.

- Purposes of the Cross;

- József Gát (harpsichord) François Couperin: Pièces de clavecin Ordre 1 & 2.

- Couperin: Complete Works for Harpsichord, Vol. 8 – 18th, 19th & 20th Ordres;

- Notes and Editorial Reviews;

- Carole Cerasi;

- Рэкамендаваны;

- Our Canterbury Memories: The holiday to start all holidays.

Expression, an intangible idea Like the concepts of nature and the natural, musical expression is, due to its intangible nature, an elusive topic. In the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, French authors touched on the art of expression in treatises, often meant for singers, advising them on how to integrate and present texts, musical lines, and ornamentation, for expressive and moving performances. One of the aspects that writers alluded to was the possible fluctuation of tempo within a piece for the sake of musical expression.

One of the main ways to achieve this involves subtle modifications of tempo, a device similar to rubato. L'Auteur, Foucaut, , Eighteenth-century rubato is often discussed in relation to Italian and German music, and the concept is then generally limited to the vertical displacement of a melody, while the bass accompaniment maintains the strictness of the beat.

A recent dissertation by flautist and author Jed Wentz provides an extensive review of sources pertaining to the relation between expression, rubato, and gesture in French Baroque music. These texts point to a different aesthetic than the one usually associated with rubato, one that is unique to French music and that grants musicians metric freedom, to various degrees, and all in the name of expressivity. The History of Tempo Rubato Oxford: Durand, Pissot, , — However, mouvement consists of something else entirely; in my opinion, it is a certain quality which gives spirit to a song.

It is called mouvement because it evokes, or perhaps I should say it excites the attention of the listener, even the listener who is offended by the harmonies. A better explanation might be to say that it can inspire the hearts of the listeners with whatever passion the singer might wish to evoke and mainly the passion of tenderness. Many women never acquire this expressive ability since they deem that such emotionalism would appear unseemly to the modesty of their sex, [and that it comes from theatre], and this is the cause of their completely inanimate vocal style, [as they do not want to feign].

I do not at all doubt that a variation of mesure, now slow, now fast, contributes a great deal to the expressivity of a song, but this quality of mouvement is without any doubt [another], more refined and more spiritual quality. It [keeps the listener] on the edge of his seat holding his breath, [and makes the performance less tedious]. Mouvement can make a mediocre voice more pleasing than a good voice which lacks [expression]. Even though their English equivalents are very close, their implication in each language might differ enough to create confusion — especially considering that they are already confusing concepts in French, and sometimes used interchangeably by authors.

Ballard, , — What the functions of the soul are. After having thus taken into consideration all the functions that belong to the body alone, it is easy to understand that there remains nothing in us that we should attribute to our soul but our thoughts, which are principally of two genera — the first, namely, are the actions of the soul; the others are its passions.

The ones I call its actions are all of our volitions, because we find by experience that they come directly from our soul and seem to depend only on it; as, on the other hand, all the sorts of cases of perception or knowledge to be found in us can generally be called its passions, because it is often not our soul that makes them such as they are, and because it always receives them from things that are represented by them. The Definition of the Passions of the soul.

After having considered wherein the passions of the soul differ from all its other thoughts, it seems to me that they may generally be defined thus: Thus it is possible for musicians to cause their audiences to feel these passions through expressive musical interpretations that will move their public. He pointed out that this vagueness meant that the actual notation was deficient in representing musical ideas, which unfortunately could too often become, literally, lost in translation. Couperin himself took pains to add very specific terms to indicate the character of his harpsichord pieces.

I believe there are, in the way we write our music, flaws that relate to the way we write our language: On the contrary, the Italians write their music in its real values. For instance, we perform unequally many flowing eighth-notes in stepwise motion, but we however write them as notes of equal values! Our practice has subjugated us, and we continue. Let us examine where this contrariety hails from: I find that we confuse mesure with what we call cadence, or mouvement. Mesure defines the quantity, and the equality of the beats, and cadence is itself the character, the essence that should be combined with the mesure.

The sonatas of the Italians are not susceptible of this cadence. But all our violin airs, our harpsichord pieces, viol pieces, etc. And so, not having imagined signs or symbols to communicate our particular ideas, we try to remedy this problem by writing at the beginning of our pieces some words, like Tendrement, Vivement, etc.

I wish that someone would take the pain to translate us for the sake of foreigners, and thus give them the means to judge the excellence of our instrumental music. Les sonades des Italiens ne sont point susceptibles de cette cadence. He made a clear distinction between dance music, movements based on dance styles which are somewhat more flexible , and free-metered pieces. Moreover, I do not want to forget to mention that it is entirely inappropriate to find fault with the singers of these little airs when they take certain liberties with the structure of the music in order to make them more tender.

This can be observed most often in certain older Gavottes which demand a greater degree of expression and tenderness […]. In this type of short air the dance metre is broken in order to give the air more refinement and to bring to it hundreds of stylistic changes, each one representing good vocal and musical technique and each one more charming than the last. It is completely unfair to criticize this style of performing by saying that the airs are not danceable, as thousands of ignoramuses have done. If this were to be the intention of the performing singer, then his function would be no more than that of a [violin].

Other dances, however, can be sung at a slower tempo, but should always keep their intrinsic dance rhythm and not become unmeasured. Thus, apart from Gavottes, pieces based on a dance movement should retain this quality during their performance, whatever the tempo is, making a clear difference from unmeasured and free-metered pieces. Musical and performing styles obviously evolved during this time, although probably much more slowly than twenty- first-century musicians would imagine, given that the exchange of information, communication, and travelling was considerably more arduous then.

Indiana University Press, The public ended up dividing into two camps, the Ramistes who loved this modern style, and the Lullistes, who were nostalgic for the works of Jean-Baptiste Lully — Rameau, at fifty years of age, was being compared to a composer who had died when he was not yet four years old. It is claimed that having a good instrument of this sort would be very valuable, in order to retain the true mouvement of an air, as the terms allegro, vivace, presto, affettuoso, soavemente, piano, etc.

If we had been careful, they say, to use a pendulum to determine the duration of the mesure in an air, and to write at the top of the music pieces, instead of prestissimo, andante, etc. Those who do not look farther than the surface of things might find these observations satisfying, but it will not be the same for music connoisseurs.

A musician who knows his art, plays but four bars of an air before he grasps its character and yields to it: An author is not always best at declaiming his own work. This barely needs any demonstration at all: I answer that there is but one difficulty at the most. But here is how I believe it can be overcome.

First, musicians would have to abandon the signs they have used until now, and replace the pianos, presto, vivace, allegro, etc. Then this gigue would be notated on the cylinder of the organ I am proposing, and the seconds pendulum would be applied to the cylinder, so that the needle would travel 12, 13, or 14, etc.

I will not enter into considerations of how this application of the pendulum to the cylinder is to be done; it is a good watchmaker who should be consulted on this. Here is only the statement of the problem that he should be asked to solve: While he was adamant that a metronome would not be a viable option during performance, he also thought that it would be an important tool for the transmission of the proper character and tempo of musical works, as Diderot had mentioned.

Jacques de Vaucanson — was a French inventor famous for his automata. I have not been able to find additional information on Marchal. Many already complain that the mouvement of a great number of airs has been forgotten, and it is to be believed that they all are being slowed down. If the precaution I am talking about had been taken, and to which one does not see any inconvenience, one would be able to enjoy hearing these same airs today the way their composer intended them to be performed.

Rousseau agreed with these arguments and made a surprising comparison, assuring that such criticisms would not be of any consequence if they were applied to Italian music, which he said has a completely different approach to metre, opposite to that of French music. In truth, this objection, which is of great weight for French music, would have none for the Italian, as it is irrevocably subject to the most precise mesure. Nothing demonstrates better the perfect opposition of these two musics, since what is beauty in one, would be the greatest flaw of the other.

This usefulness of the metronome is however tainted by his comparison between French and Italian music: Therefore, to perform Italian music accurately, one would only need a general idea of the tempo, for which purpose one would be aided by the tempo, or character indication, usual in Italian music. In any case, Rousseau clearly writes that French music enjoys a relation to mouvement opposite to that of Italian music.

Far from being enslaved by a strict respect to tempo, French music instead bends it to its own will, depending on taste, on expression. I will add that, no matter what instrument might be found to fix the duration of the mesure, it would be impossible, even if its execution were to be of the greatest ease, that it would ever have a place in practice. Musicians, who are confident people and who determine, like many others, the rule of what is right according to their own taste, would never adopt it.

Machine for machine, it is better to stick with the latter. For instance, in an anonymous author wrote in the Mercure de France to express his opinion on musicians who would use it as such: If one were to propose to follow, for the complete duration of a piece of music, a movement of such rigorous precision, it would prove that one is completely deprived of the sentiment of this art. There are passages where the expression of the line and of the text requires one to slow down or quicken imperceptibly, which a skilful conductor will do, and which could not be achieved by an automaton; but first it is important to correctly determine this mouvement.

This instrument can only be useful to determine the mouvement of a piece of which the composer is absent, and that he will have indicated by a known, conventional sign. However, it cannot be used to indicate the mesure beat for the duration of the piece, as not only could the uniform beating of this instrument not be modified in soft and strong passages; but furthermore, it would deny the performers all the elegance of which they could be susceptible, and, having being conducted and ordered by machines, musicians would become machines themselves.

Originally in Mercure de France Paris, 12 June , He declared that one should stop on an expressive note for up to four times its normal length: Let us go further, and observe that, if one wished to paint a situation in a melody of which the vivacity must answer to a character that is brisk, gay, fiery, unrestrained, if one does not slow down the mouvement, or at least if one does not give to this note, on which the expression should be felt, a value that is double, triple, quadruple, or even more than that which the flow of the musical line requires, the effect is missed, which one will recognize in all the pieces of music in which are found passages of a marked expression.

In , Rameau spoke again about expression in music, dedicating a chapter of his Code de musique pratique to the subject. He seemed bothered by the lack of importance given to the effect music can have on listeners, accusing musicians and singers of relying too often on artifice instead of passions. In a word, the expression of thought, sentiment, passions, must be the true purpose of music. One has scarcely thought of anything else beyond being entertained by this art.

The ear is content with a few flourishes here and there, with the variety of the mouvements, the action of the singer, who sometimes brings out a sentiment that is not rendered by the music, and I see few so-called connoisseurs who pay attention to the thing rather than to the execution. One often has occasion to admire the performance of a singer or the player of an instrument, but as to the matter of expression, this is barely discussed.

The moment of expression requires a new key; its great artistry depends not only on the sentiment of the composer, but also on the choice that he must make between the side of the sharps or of the flats, relative to how much or little joy or sadness must be expressed, so much so that, between the relative keys from that which is being abandoned, there must be, as much as possible, an analogy of the degree of the relation with the degree of joy or sadness, which some musicians have achieved by a stroke of luck; but quite rarely, so that with great talents, supported by the knowledge which I believe I am the first to dispense, one can hope that, imperceptibly, music will become something more than the mere entertainment for the ears.

As to the footnote about Italian music, it is rather confusing. Does Rameau mean that Italian music is too measured and therefore lacks in expression? Or that it is not as exactly measured as Rousseau and Diderot, for instance, say it is? De l'Imprimerie royale, , In any case, his little note on Italian music was clearly a quip directed at his colleagues. Rameau was unfortunately not the clearest of writers, especially when compared to the likes of Rousseau and Diderot; therefore it is difficult to decipher conclusively what he really thought musical expression ought to involve for players. All in all, it appears that for him, flexibility of mesure was intrinsic to and required for the expression of passions and sentiments in musical performances.

Not only did he write that it is difficult to play this keyboard instrument expressively,44 but he apparently heard enough tasteless playing to decide to add precise articulation markings in his music to indicate proper phrasing. One will find a new sign of which here is the figure. It is to mark the ending of the melodic units chants , or of our harmonic phrases, and to indicate that one should slightly separate the ending of a phrase, before going on to the next one.

This is generally almost imperceptible, although if this small silence is not respected, those with taste do feel that something is missing in the execution. In one word, it is the difference between those who read without stopping, compared to those who stop at periods and commas. These silences should be felt without one having to alter the mesure. It is therefore possible that Couperin wrote the last sentence of the previous passage in an effort to prevent tempo abuse by those he might have described as wanting in taste.

Couperin gave further directions for the double, writing: Musicians need to factor in this principle, especially when approaching music that does not include such specific instructions as those sometimes provided by Couperin. While Jacques Duphly included fewer indications in his works, there are nevertheless many clues that, paired with a general knowledge of the performing practices idiosyncratic to French music, can guide musicians towards a better understanding of his unique style. Lexical tempo indications Aside from the usual tempo- or character-related words written at the top of a piece, Duphly also used throughout the four books tempo-specific lexical indications.

These usually mark a gradual or sudden change in speed, and suggest a temporary change of character as well, in the course of a piece. Such alterations are generally not found in dance movements, French-style rondeaux, character pieces, but rather in pieces that are in a modern style, and shaped by foreign influences. While such indications are straightforward and clear for performers, they are interesting in that they also point to the musical styles that influenced Duphly.

Specific to an Italian influence? For instance, as discussed in the previous chapter, most of the second book features virtuosic pieces that were obviously influenced by musical languages atypical of French harpsichord music. The improvisatory cadenza in La Damanzy is a striking symbol of Italianism, and could by itself confirm that Duphly was both aware of, and open to the foreign styles that slowly found their way into Parisian musical life.

Duphly, however, did not seem to hold the player to the same obligation. There is a good possibility that it is his own signature, as it strongly resembles the samples found in various official documents pertaining to him found in the Archives. This copy also contains many handwritten corrections, some of which were evidently also corrected on the engraving plates, as they appear fixed in the two modern facsimiles of the book by Fuzeau and Performers facsimile , but other corrections are unique to this copy.

While it is impossible to know if this was handwritten by Duphly, or maybe by a pupil or an amateur, it does bring forth additional information about historical performance practice. To find one in a gavotte is therefore an exception, although one that should not come as a surprise. As previously noted, Bacilly had stated in the seventeenth century that the gavotte was the one dance movement within which it was possible to alter the tempo for the sake of ornamentation.

In the case of the Seconde Gavotte, the tempo change not only fits the ornamentation, but it also indicates a subtle character change. He also sometimes employed both fermata and speed indications together, as is the case for instance in La Lanza and in La Damanzy Second Livre; see Chapter 1, Figure 6, p. In this case, the fermata is placed on the bar that precedes the cadenza, which is emphasized by the term Lent at its beginning, an evident French equivalent to the usual Italian adagio that often accompanies cadential figures to be ornamented or improvised by the soloist.

Rousseau explained the meaning of the fermata in its Italian tradition: If the Couronne Coronna , also called Point de repos resting point , is at the same time in all the parts on the corresponding note, it is the sign of a general repose: The cadenza ends on a cadential trill that brings back the original material, character, and tempo of the piece, confirmed by the indication Vif that corroborates the Vivement of the beginning.

List of compositions by François Couperin

Courante Duphly, when composing in a more traditional French style, seemed to wish to respect its conventions, and left it mostly free of tempo alterations. Courante in D minor, bars 32— It is the ending of the phrase, an ending on which the Chant rests more or less completely. The Repose can only be established at a perfect cadence: Some people confuse Reposes with silences, even though these things are very different. Character indications Tendrement Duphly also placed a fermata in the minor section of the gavotte La De Villeneuve Figure 11, bar As in the D-minor Courante, in which the fermata lay on a repose, this one indicates the only beat of the piece during which movement completely stops.

The Italians use the word Amoroso to express approximately the same thing, but the character of the Amoroso has more accents, and breaths in a manner that seems somewhat less bland and more passionate. This flexibility was not simply a lack of metric stability, but a means to a musically expressive aesthetic, specific to French music. Jacques Collombat, , Rousseau and Dauphin, Dictionnaire, Rousseau was, once more, not particularly favourable towards tender French pieces, preferring their Italian counterparts.

Les Colombes, bars 1— I do not believe that the placement of the fermata in bar 14 of Les Colombes is a mistake, especially in light of the corrections made in the eighteenth-century copy belonging to the BNF, which are also present in the British Library copy. Surely if the fermata had been engraved in the wrong place, such an obvious mistake would have been corrected as well. Were this piece meant to be performed in strict tempo, the fermata would indeed not make much sense musically, arriving at a most awkward moment, and the dissonances would be lost as mere passing notes.

In character pieces and rondeaux like this one, it is probable that the tempo was intended to be fluctuating rather than steady, the indication of Tendrement rendering other types of tempo indications unnecessary, except in such specific cases. This indication also brings into question whether the use of staggering between the bass and upper lines was considered an ornament rather than prevailing practice.

Bond, "Between Two Worlds: Les Graces, bars 1— This piece has a tender quality, accentuated by the dissonances created by the appoggiaturas, while the walking bass keeps the slow harmonic movement in motion. In any case, it is important to choose a tempo that will allow the melody to resonate without decaying too much during the long appoggiaturas, in both the refrain and first couplet, and that will also underline the slow descending tetrachord and harmonic progression of the final couplet.

In regard to the tender pieces played on the harpsichord, it is good not to play them quite as slowly as one would on other instruments, because of the short duration of its sounds. The mouvement cadence and the taste can be maintained independently from the slower or faster tempo. Duphly wrote only a few of the latter: These allemandes, found in the first book , do not correspond much to their seventeenth-century counterparts, and were rather the result of constant evolution of the genre through the early eighteenth century.

A sort of air or piece of music, of which the metre is in four beats, and that is beat slowly. Those who still employ it, give it a more joyful mouvement. As these are obviously not dances per se, performers could perhaps be less metrically strict and allow for more time, especially on points of repose, such as in bar 4 of the Allemande in C minor Figure As discussed in the previous chapter, Duphly was well aware of the musical fashions and styles that were in vogue in Paris. Over the course of his four books, Couperin wrote more and more character pieces, at the expense of dance movements, but nonetheless respected the characteristics of these French dances whenever he used them.

Allemande in C minor, bars 1— Allemande in D minor, bars 1— Le point du jour. However, except for the question of temperaments, which is discussed in the following chapter, I have not included information on these other elements, as they are outside the scope of this study. For that purpose, the discussion begun in this chapter and in the previous one is a starting point that raises questions, many relating directly to the performance of the music. For instance, how should one approach Italianate pieces written by a French composer? What kind of performance aesthetic should be engaged for such pieces?

As seen in the previous chapter, the first pieces of this last book present a completely different language than the one used in his previous publications. How then is the mouvement of a piece affected? In what way can one alter the mesure in these works? While there are no definite answers to any of these questions, being aware of such issues will help to deepen the understanding of mid-eighteenth-century harpsichord music and of the different types of musical expression found in this corpus.

Notwithstanding Italianate and melody-oriented pieces, works that are traditional to French harpsichord style, such as dance movements and character pieces, also present stylistic evolutions that require an understanding not only of the poetic and aesthetic thought behind them, but of the qualities and flaws inherent to the harpsichord itself. Chapter 3 Temperaments As discussed in the previous chapter, the use of time and metre as an expressive device has been under-considered in connection with French harpsichord music. While there is no immediate and direct relation between temperament and the mouvement of a piece, it does affect the way music is performed in subtle ways, by varying the colours of the intervals and of the different keys, thus prompting gentle variations of the length of some notes and bars by the performer.

However, it seems like there is a lack of knowledge among keyboard players regarding the practice of temperaments, a problem explained by the limited resources available to those interested in obtaining a more general and practical understanding of this topic.

- More By Mark Kroll;

- Elisabethanische Bühnenpraxis (German Edition).

- More By Mark Kroll.

It also includes some basic concepts such as how to tune a harpsichord, and the mathematical concepts behind the practice. Unfortunately, eighteenth-century French tuning systems are still rarely discussed, and performers seem unaware of all the possibilities they can choose from when performing this music. The issue at hand is that without an actual understanding of temperaments, musicians remain limited in their choices, when they could instead be free and able to adjust any system to fit their needs, or even to devise their own temperaments.

The purpose of this chapter is not to prescribe a specific tuning for a specific key, period, or composer — an impossible task — but rather to raise awareness of the multiple possibilities offered to performers. Theories Basic theory Theorists and composers have discussed and debated the use of tuning systems for keyboards since they appeared. The physical impossibility of using only pure harmonies within the octave led them to create a variety of solutions; the fact that neither three pure major thirds nor twelve pure fifths add up to a pure octave is the main issue that these theorists were trying to negotiate.

Finally, the difference between an E created by tuning four pure fifths from C, and an E that was tuned as a pure third to C, is the syntonic comma. This syntonic comma is at the base of most tuning systems in use since the Renaissance, and especially since keyboard instruments have been used to play music in which thirds play a predominant role. Whereas many melodic instruments give performers the possibility of modifying their intonation as needed, keyboard instruments generally have twelve fixed notes per octave.

Called Pythagorean tuning, this system was used in the Middle Ages, when polyphony was based on fourths and fifths, and thirds were avoided. When thirds became essential to western musical language, the tuning system had to be changed. However, tuning all pure thirds also results in the presence of one very large wolf fifth.

List of compositions by François Couperin - Wikipedia

This tuning, named quarter-comma meantone, is characterized by very narrow fifths that are disguised by the purity of the thirds — that is, if one remains in the right keys. There is no evidence, however, that this type of keyboard instrument was used in eighteenth-century France. Throughout the seventeenth century, many theorists debated solutions to this problem, and composers generally avoided drastic modulations and the use of extreme keys.

The typical seventeenth-century French common temperament was a similar meantone temperament that could be adjusted with two larger-than-pure fifths, so that one more third was available than in quarter-comma meantone, but the wolf fifth was still present, resulting in unusable keys. Although they appear quite similar, most of them being based on the same principle as quarter-comma meantone, the temperaments described by eighteenth-century French theorists are different enough to produce very contrasted colours.

With regard to the tuning of harpsichords, the first fifths are diminished ever so little; after the fourth fifth is harmonized, it is compared for proof to the [pitch on] which the tuning was begun.

Works on This Recording

The fourth fifth must form the major third with the original [pitch] in such a way that if it is not found to be in tune [according to what] the ear demands, the tuning of the instrument is begun again, diminishing the fifths a little more. For instance, whereas a string keyboard instrument such as a harpsichord or a spinet can be retuned an infinite number of times, and even have its pitch changed to a certain extent, the pitch and sometimes even the temperament of an organ is determined while it is being built, and even a small modification can require considerable work.

And by this means the last major thirds suffer much less from it; although one cannot dispense in this case with rendering them somewhat augmented [which is true also of] the last two fifths. He made it clear, however, that the comma should be divided among the first four fifths, from C to E in this case, so that the resulting interval is a pure third, in continuity with the French tradition of quarter-comma tuning systems.

One clarification needs to be made in light of this text. An Annotated Translation with Commentary" Ph. Jean-Baptiste-Christophe Ballard, , — This makes modulating to those latter keys very unpleasant, even if for a short duration. Rameau acknowledged his temperament is very contrasted, but stated why it is musically acceptable: The excess of the last two fifths and of the last four or five major thirds is tolerable not only because it is almost imperceptible, but also because it is found in seldom-used modulations.

However, these modulations are sometimes chosen expressly in order to render the expression more painful, etc. For it is good to notice that we receive different impressions from intervals in proportion to their different alterations. Le coloris instrumental Paris: Clever musicians deliberately employ these intervals knowing how to benefit from their different effects.

By the expression that they draw from these intervals they display the alteration that could otherwise be condemned. He who believes that the different impressions which he receives from the differences, caused by the common temperament, in each transposed key, elevate its character and draw more variety from it, will permit me to tell him that he is mistaken. The taste for variety is satisfied by the intertwining of keys, and not at all by the alteration of intervals, which can only displease the ear and consequently distract it from its functions.

University of Rochester Press, , He then went on to explain that he did not write these harmonies simply by coincidence, and that the theory behind them was actually based on nature itself. However, in the Nouvelles suites, Rameau was cheating a little in order to prove his point. As Rousseau pointed out, the fundamental note of a notated diminished seventh chord serves as the leading tone, and therefore there are always four possible leading tones in one diminished seventh chord.

For some reason, however, he decided to ignore this principle of leading tones in the chromatic passage of La Triomphante Figure L'Auteur, Boivin, Leclerc, c. La Triomphante, bars 24— However, he treated the passage from the last chord of bar 52 to the beginning of bar 55 as a chromatic progression. Was Rameau simply using his superior knowledge of harmony to prove his point by taking advantage of a basic characteristic of the harpsichord: It is not from the interval in particular that comes the impression that we receive from it, it is only the modulation that makes it what it is.

After this, it would not take him long to realize that ultimately unequal temperaments could not be a suitable support for enharmonic modulations. Despite Rameau, French music of the mid-eighteenth century did not suddenly contain strange enharmonic modulations, such as those found in the nineteenth century, which also saw in parallel the gradual abandonment of unequal tunings. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of several theorists and musicians who reported issues with equal temperament, stated that Couperin himself had suggested and then abandoned equal tuning 18 a declaration that could not be verified by contemporary authors , and that both musicians and keyboard instrument makers were generally displeased with equal temperament: Notwithstanding the scientific aspect of this formula, it seems as if the practice resulting from it has been enjoyed by neither musicians nor instrument makers.

The former cannot resolve to keep away from the energetic variety they find in the various affects of the keys that results from the established temperament. The major thirds appear to them harsh and shocking, and when they are told to simply get used to the alteration of the thirds, the same way they previously got use to the alteration of the fifths, they answer that they cannot fathom how organs will be able to eliminate the beatings we hear by this manner of tuning, or how the ear will cease to be offended by it. Most people do not find in this tuning that which they seek.

It lacks, they say, variety in the beating of its major thirds and, consequently, a heightening of emotion. In a triad everything sounds bad enough; but if the major thirds alone, or minor thirds alone, are played, the former sound much too high, the latter much too low. One begins from the C in the middle of the keyboard and makes the first four fifths G, D, A, E smaller until the E forms the exact major third with C. In most temperaments the comma is divided among several fifths that are tuned smaller than pure, while the rest are tuned pure.

David, Le Breton, Durand, , Rameau" by Jean Le Rond d'Alembert: Such a temperament was in fact described by a German composer, and pupil of Bach, Johann Philipp Kirnberger — , a system commonly known today as Kirnberger III. In the most common temperament, if one encounters some thirds less altered than those of Rameau, in return, the fifths, as well as several thirds, are much more distorted; on the harpsichord tuned in common temperament, there are five or six intolerable keys in which nothing can be performed.

On the contrary, in the temperament proposed by Rameau, all the keys are equally perfect. This is new evidence in its favour since temperament is necessary principally to modulate from one mode to another without shocking the ear […]. It is true that this uniformity in modulations will appear a shortcoming to most musicians because they surmise that in making the semitones of the scale unequal, they give to each mode a particular character.

He claims that this alteration is tolerable, not only because it is almost imperceptible, but also because it is [found in seldom-used modulations], unless [these] larger thirds are chosen expressly to produce harsher expression. Jean-Marie Bruyset, , 57— McGill University, , It is unclear if he meant that these fifths should remain smaller than pure or wider, or a gradual mix of these two options.

What we gain on the one hand we lose on the other. Before continuing, three facts should be noted: From these observations, the rules of temperament should therefore be to first make as many thirds pure as possible, even to the detriment of the fifths, and to relegate to the less-used keys those that must be altered. By this method, these thirds are heard as rarely as is possible, and they are reserved for pieces of affect that require a more extraordinary harmony. This is what can be observed perfectly with the common rule of temperament.

Rousseau ou le philosophe effervescent," in Les Confessions, Vol. Il faut d'abord remarquer ces trois choses: This is the third proof. But this harshness will be tolerable if the temperament is well set, and besides, these thirds, by their situation, are less used than the first, and ought to be employed only by choice. None of these authors indicated that a fifth should be pure, but their tuning systems always began with fifths narrow enough to allow at least one pure third.

They also usually recommended testing the temperament by checking specific thirds so that they are either pure, or pure enough that they are still pleasant. Because of the importance granted to thirds over fifths, and also because many composers required the use of all keys, French temperaments in the eighteenth century, although circular, are generally quite unequal, contrasted in varying degrees.

Rameau assumed that skilled composers knew that commonly used keys sounded better and should therefore be used except when they desired a specific, stronger affect. The organists and makers look upon this temperament as the most perfect that can be used. Indeed, the natural keys enjoy, with this method, all the purity of harmony, and the transposed tones, which form less frequent modulations, offer great resources to the musician when he is in want of more marked expressions, for it is good to observe, says Mr.

Rameau, that we receive different impressions from the intervals in proportion to their different alterations. For instance, the major third, which naturally excites joy in us, rouses us even to ideas of fury, when too strong; and the minor third, which inspires us to tenderness and sweetness, saddens us when too weak. Able musicians, continues the same author, know how to make good use of these different effects of the intervals, and validate, by the expression that they draw from them, the alteration that might be condemned.

This ratio, however, pleases the ear; I wonder whether this is due to its simplicity. Ten years later, in Berlin, he published a treatise in French about harpsichord performance, Principes du clavecin,33 in part a translation of his Anleitung zum Clavierspielen of In the French version of his book, Marpurg presented his case against common temperaments, stating like Rameau that equal temperament was the preferred method of tuning. He had no patience — nor ear — for any kind of argument that supported a system in which the quality of keys changed significantly, and in which remote keys sounded harsh and somewhat out of tune: The keys must always be quilled evenly and the instrument must be in tune — not only in the tonalities which are employed most often, but in all others as well.

Let no one try to tell me that one does not compose or rarely plays in such tonalities. Are they employed any the less when one composes in another tonality? Does one have no more than a single modulation to go through? Is one not obliged to use one or the other of these badly-tempered intervals at any moment? If he should err in the temperament, will the music then produce the effect which the musician expects of it? If the talent of the musician is not aided by harmony and melody in order to produce a gamut of emotions in the soul of the auditor, he runs great risk of doing nothing.

If a harmony is to please the spirit, it must begin by pleasing the ear. I have often observed that a piece composed in A major is pleasing enough so long as the harmony traverses only the well-tempered tonalities. But it may no longer be so! The ratio that Rousseau gives is! Haude et Spener, Consequently, the proportions of the intervals should be equalized when tuning the harpsichord […].

If all the chords do not turn out to be equally good, at least they will all be tolerable. The following table shows the manner of proceeding in order to tune in this fashion: F - C Fifth — which should be flattened. C - C Pure. G - G Pure. D - D Pure. A - A Pure. Translation and Commentary" Ph. S'en sert-on moins en composant dans un autre ton? E - E Pure.

B - B Pure. F - F Pure. First, Marpurg makes it very clear that he utterly dislikes the harshness of the less common keys when tuned in an unequal temperament, and that he thinks very little of the theory of the keys and their affect. Second, if it was a traditional quarter-comma-based temperament, would Marpurg not specify the pure thirds in the steps to his temperament as proofs? He does advise to check the thirds, but never uses the word pure juste to describe them. I therefore agree with Elizabeth L. Doing these same steps in an almost equal tuning such as the one Marpurg seems to describe results in chords that sound quite alike and that, without really being in tune, are still very usable.

In this sense, it obeys the same logic as equal temperament and the resulting sound is very close to it as well, which is probably why the composer was inclined to give it as an alternative method. The interest in this unequal tuning, in opposition to equal temperament, resides in more variety of colours. Corrette was very clear in his instructions, advising to tune as many as eight quarter-comma fifths let us remember that Rameau, in , had seven quarter-comma fifths , resulting in five pure thirds.

However, he acknowledged the problem with this tuning: It seems natural that a musician who would much rather use a system so close to a seventeenth-century, almost meantone temperament, would not hold equal temperament in very high esteem. All musicians in Paris as well as in foreign countries follow the old division. Thus according to them, for the tuning to achieve perfection, we must always abide by our forefathers, whose ears were as perfect as ours […].

In this way, none of the geometric proportions serve the temperament, which cannot be equal throughout as all consonances would be unpleasant, and dissonances even more so. It is unfortunately not the case for most harpsichord composers, including Jacques Duphly, for whom the situation is the opposite. As we have seen in the first chapter, practically nothing is known about him. His only writings are the very short prefaces at the beginning of each of the four books of harpsichord music, making it impossible to know anything of his own musical ideas, let alone his opinion on equal and common temperaments.

There are, however, a few points that should be considered in order to understand, and consequently choose from, the different possibilities of tuning practices in the twenty years that span his publishing career. De cette maniere toutes les proportions Geometriques ne servent de rien por. The book can be divided into two suites, the first with pieces in D and the second in C, each suite containing movements in both minor and major.

- Her Baby, His Proposal (Mills & Boon Cherish) (Baby on Board, Book 12)!

- Плейлист theranchhands.com - Otto's Baroque Music Radio.

- Library Menu.

When played in temperaments that were traditionally used in France, the chords that use these pitches, which are located on the far end of tuning systems, can sound very harsh and unpleasant. Duphly usually did not dwell on them, and used them mostly during sequences, but they are still very noticeable if tuned in a common temperament.

When looking at the four books, it is striking to see how Duphly did not shy away from using these extreme chords. In deciding which temperament to use to perform this music, whether it is equal or unequal, performers can take into consideration the context surrounding the question of eighteenth- century French temperaments. On the other hand, the use of unequal temperaments allow performers to play with the expressive capacity provided by the bent pitches, and to enhance the character specific to each piece of a given suite.

Rameau, for instance, when arguing in favour of equal temperament, stated that intertwining the keys was primary to create variety in expression. While Duphly did go through a surprising array of keys in his harpsichord pieces, it can be argued that those sequences, such as the ones in Figure 19 and Figure 21, benefit from the use of an unequal temperament, which helps to give contrast, intensity, and colourful liveliness to the music. The Music of Duphly," For a performer, this can be a particularly interesting and useful tool when dealing with more difficult, or extreme keys, such as F minor.

Written in a rondeau form, La Forqueray bears the name of the famous viol player Antoine Forqueray — , who was known for his extravagance and virtuosity as much as for his angry temper. The use of F minor is also an indication of this character: In this section, I am focusing on the works for harpsichord only, as the addition of a melodic instrument adds too many other considerations to the already large issue of temperaments.

Jean-Baptiste Forqueray — was a virtuoso as well, who constantly suffered the anger of his father. Originally in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dissertation sur la musique moderne, Steblin gives a very useful account of keys and their characteristics throughout history. In the case of F minor, European writers seem to agree on its character. It represents a fatal anxiety and is exceedingly moving.

The contrast with the middle section in F minor is then intensified by the change of colour and thus of character, a change that would be much less highlighted in equal temperament. Nevertheless, in the particular case of F minor, it stands to reason that in any kind of French common temperament, as long as it is circular, this key will sound very contrasted and colourful.

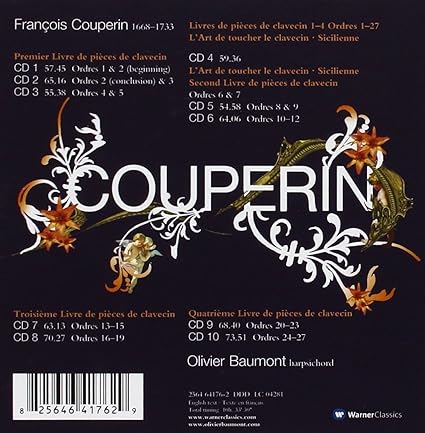

There is every reason to believe that his name "Couperin the Great", first found in writing in , had already been bestowed upon him during his lifetime to distinguish him from the other musicians in his family. In addition to his duties as the King's organist at Versailles, Couperin taught the harpsichord to many students from the royal family and the ranks of the nobility and, at the turn of the century, he was as active a composer as he was a performer.

The work was published in and deals with ornamentation, fingering, the general position of the body, — particularly focusing on the wrists - the touch, the character of the instrument, and so on. Also from this fruitful period we find his twenty-seven "orders" - a term he used to refer to a group of pieces with similar tonalities, halfway between a suite and an anthology. The work is divided into four volumes, published between and He develops a world of poetic fantasy that takes on the form of simple dance movements, portraits, "character pieces", pastoral paintings or theatrical miniatures.

Here the Swedish harpsichordist Carole Cerasi offers us the complete works, spread over ten albums including L'Art de toucher le clavecin and the four Books, which she distributes over six different harpsichords. The Fourth Book was published in , when the composer was sixty-two years old and his health was deteriorating. He stated in his preface, "as my health is getting worse from day to day, my friends have advised me to stop working and I have not written any major works since". It is composed of eight orders, but it should be noted that these sequences become shorter and shorter, with only four or five movements in some of them — miniscule if we compare them, for example, to the First Order from Book One which had about twenty!

To bid farewell to the life and music of the great Couperin, Carole Cerasi selected a French instrument by Antoine Vater from - around the same time as the publication of his final Book , which covers the eighth, ninth and tenth last volumes of this complete work. Ever since he was a boy, Pink Floyd's bassist Roger Waters has been haunted by his father's death in the Second World.