Trained as a geographer, Wilford argues that the success of the megachurch comes from its innovative use of scale in the postsuburban fringe of large cities. Wilford argues that socio-spatial differentiation is a major factor for explaining why megachurches thrive while other religious congregations decline.

- ;

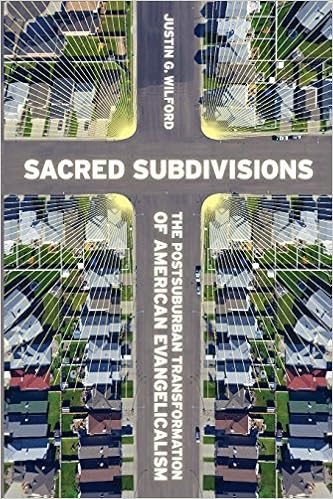

- Sacred Subdivisions: The Postsuburban Transformation of American Evangelicalism?

- Petits Departements et Grandes Regions Proximite et Strategies (Administration et Aménagement du territoire) (French Edition).

- ;

- The Perioperative Medicine Consult Handbook.

- .

Because postsuburban lifestyles are so fragmented, socio-spatial differentiation creates particular constraints and affordances for religious congregations. Diverse secularization theorists have identified differentiation as a core process of modernity, but sociologists of religion have underappreciated its geographic dimension. Socio-spatial differentiation makes it particularly difficult for religious traditions to create a sense of community that binds work, family, and civil society.

- Join Kobo & start eReading today.

- Les 100 mots de la régulation: « Que sais-je ? » n° 3871 (French Edition).

- Find a copy in the library.

- Loublié dOutreau (French Edition)!

Saddleback Church does not thrive by creating a gemeinschaftlich community-like gathering bound by repetition, ritual, and homogeneity. I recommend this book to cultural sociologists, sociologists of religion, and scholars interested in civic engagement and political socialization. Socio-spatial differentiation seems to be a major force behind a variety of cultural trends, and Wilford makes a valuable contribution by highlighting this common thread running through multiple literatures. The case of megachurches also sheds light on a broader question: Long-standing debates about social capital and civic engagement come into clearer focus when viewed through a geographic lens.

Anthropological Quarterly

This book would be an excellent choice for graduate seminars and advanced undergraduate classes on religion or urban studies, in part because of its clear and multidisciplinary discussion of secularization and modernization debates. Most of the introductory chapters assume a broad working knowledge of sociological theory, which makes the book less accessible to well-informed laypeople and undergraduates. The book's masterful discussion of theory is admirably concise and jargon free, but it does limit the book's audience. For undergraduate classes, I recommend excerpting the more empirical chapters.

One of the book's limitations is its rather thin description of religious practice at Saddleback Church.

"Sacred Subdivisions: The Postsuburban Transformation of American Evang" by Gretchen Buggeln

Wilford spends a great deal of time setting up Jeffrey Alexander's performance theory as a lens on postsuburban megachurch life. But in the end, I did not learn as much as I had hoped to about why particular religious performances succeed or fail for postsuburban evangelicals. Following Alexander's neo-Durkheimian approach, Wilford focuses on the social facts of Saddleback's organizational life and downplays the first-person accounts of its participants.

But if the book is explaining the popularity of megachurches, that implies an argument about why individuals participate more or less, based on how they experience the cultural performances that the megachurch environment affords. We learn a great deal about how Saddleback accomplishes multi-scalar performances of religion, but not about how individuals experience religious performance in terms of place.

In conclusion, this book has important strategic implications for practitioners in the field of civic engagement: If Wilford is right, then we need to be looking for organizational forms that do what the American megachurch does so well: All organizers know that powerful movements require suburban allies. Yet, many civic engagement strategies are poorly adapted to low-density, postsuburban environments like Orange County.

Wilford's book helped me understand why this is so—and what organizers can learn from megachurch pastors. In an era where church attendance has reached an all-time low, recent polling has shown that Americans are becoming less formally religious and more promiscuous in their religious commitments. Within both mainline and evangelical Christianity in America, it is common to hear of secularizing pressures and increasing competition from nonreligious sources.

Yet there is a kind of religious institution that has enjoyed great popularity over the past thirty years: Evangelical megachurches not only continue to grow in number, but also in cultural, political, and economic influence.

Sacred subdivisions : the postsuburban transformation of American evangelicalism

To appreciate their appeal is to understand not only how they are innovating, but more crucially, where their innovation is taking place. In this groundbreaking and interdisciplinary study, Justin G. Wilford argues that the success of the megachurch is hinged upon its use of space: The Varieties of Religious Experience. Not My Idea of Heaven. Princeton Readings in Religion and Violence. An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture. Political Theology for a Plural Age. Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning. Law Enforcement and Technology. The Public on the Public. Transformations of Religion and the Public Sphere.

Worship across the Racial Divide.

Sacred subdivisions : the postsuburban transformation of American evangelicalism

Globalization, Translation and Transmission: Youth Tourism to Israel. Hans Mol and the Sociology of Religion. Being a Muslim in the World. Jewish Orthodoxy and Its Discontents. Reproductive Dilemmas in Metro Manila. The Battle for the Soul. Pope Francis as a Global Actor. Routes and Rites to the City. Prisons and Punishment in Texas. Dad 1, Dad 2.