Moran doubtless will not endear herself to her erstwhile colleagues, but for a general readership she is a facile writer who comes across as a breezy romantic. Fresh from Harvard, she decided that joining the CIA would be really cool. Before long, she decided it was even more cool to find a boyfriend. When she did, she decided to throw over the Agency and get married. To operate effectively in an overseas environment, you need to know the language and the culture and be there. Mahle spent fewer than 15 years at the CIA—well short of the normal career duration.

She shares with Paseman a desire to help satisfy this curiosity. Agency readers, especially, may wonder if this burgeoning genre of intelligence memoirs is a good thing. To be sure, ex-CIA authors publish memoirs at varying levels of seriousness and competence.

Some are bent on sharing insights into a career in what must be acknowledged to be a closed world that is a mystery to anyone who has not worked within it. They may have seen the organization and its work through a very narrow prism and have a very limited perspective. The result can be somewhat like the fable of the blind men describing an elephant. Where you touch it—and where the Agency touches you—not only forms your perception of it, but also, perhaps less obviously, limits your ability to characterize it.

Having done only one type of work in one directorate makes characterizing the entire Agency more difficult and probably somewhat skewed by the particular prism through which the author experienced it and recalls it. All three of these books are by former operations officers. This does not say that former operations officers are more inclined to go public with a grievance, or even that they are more likely to have a grievance. What it may say is simply that an operations career fits more readily with the public conception of the CIA as a place of mystique, romance, danger, and excitement.

The operations officer commands an audience simply by having been an operations officer. The result is a conviction that we ought not bog down in finding flaws and being dismissive of this genre. For one thing, this reviewer does not know of a single recruitment pitch, operational plan, or liaison relationship that was ruined or precluded by the publication of a book.

This is not the place to discuss declassification policy at length a subject separate from publication review , but it is worth noting that the CIA is hardly blameless for the fact that perhaps the three best-known initials in the world are weighted down by an aura of the sinister and suspicious.

Evidence abounds—bound and on bookshelves in growing number—that former CIA officers can offer pertinent and valuable insights without damaging national security in the slightest. Indeed, they can enhance it. Memoirs can help clear the air. They can illuminate and inform. They can correct misconceptions. They can contribute expert opinions on current issues. Roosevelt documents that he was an accomplished linguist and patriotic American.

He chose to serve his country World War II even if not on the front line.

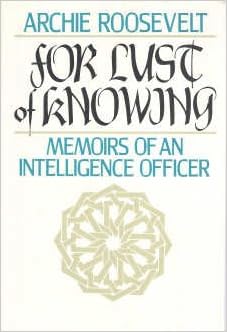

For Lust of Knowing: Memoirs Of An Intelligence Officer

His insights into both cannot be cast aside as merely politically driven. Unfortunately he also chooses to make this book more of a travelogue, salted with a few character assessments and end with wha Mr. Unfortunately he also chooses to make this book more of a travelogue, salted with a few character assessments and end with what almost becomes a political diatribe.

Almost, as in to his credit. His opinions are clearly informed and if somewhat bent to serve his view of America and his fear of the Soviet aspirations. I cannot fault the former and cannot refute the latter. There remain valid lessons to be learned by his thoughts. There are two reason why I blunt my praise by posting only 3 stars to this memoir. Having lead us to believe this would be more about his service as an intelligence officer he draws a shade across all of his service with the CIA. There are some valid reasons for this but they do not entirely excuse him from hinting at or basing later conclusions on information not shared.

Given that editors own what is on the cover of a book, the teasing may not have been original to Mr. A few thoughts on the content. Roosevelt grew up during the depression. Family connections and money seemed to mean that his America felt no depression. The term does not have its own entry in the index. In his criticisms of the Americans who allowed themselves to be taken in by the promises of Socialism and even became the dupes of Stalinist propaganda, he has no apparent thought that some of these people had lived through another, as in not the first failure of Capitalism to care about these same people.

The Work Of A Nation. The Center of Intelligence.

Roosevelt for example, owed his first three jobs to family connections including his commission as an officer in the Army. We are lucky that his skills were not wasted on the battle field but fortunately for us he was taken into the Army as a translator and member of a nascent intelligence community. Still his was not luck of the day, but the application of connections. Mr Roosevelt was an Arabist. That is he was a mostly a self-educated linguist in many of the Middle Eastern languages. Apparently at his own initiative he became learned in the various communities we tend to think of under the badly spread tent of Arabs.

I have no doubt that America benefited from his determination to learn from being in the tents, rather than the classroom. I am not sure he fully grasped the root of some of the lessons. Much of Occidental command and influence in the Middle East came from a combination of raw military and economic power, and direct colonial control. Where this had not been sufficient, some colonial powers learned to play tribal leaders against each other.

America as the newest entrant into this geography apparently never became fully adept at this last skill and was never consistent in its will to apply the first two.

Military intelligence: a list of essential readings

John Collins, who enlisted as a private in , served in three wars, and also is author of Military Geography and Military Strategy:. Obviously good for COIN. The Newest Face of War , would be my recommendations. The Dunmire article is very helpful on the career field itself and some key issues strategic intelligence faces, especially in the Army. The book is especially valuable when read with T.

James Hailer, founder, Hailer Publishing , a specialty house for military classics:.

- LAZY TURKISH PHRASE BOOK (LAZY PHRASE BOOK)!

- .

- ;

- Upcoming Events.

- .

- Rupert Leon (Author of Memoirs of an Intelligence Officer)?

He nails the war between bureaucracies better than anyone I have read, and it is one of the few books that I have consistently laughed out loud as I read it. Frankly it should be required reading for any person in a large organization.

Military intelligence: a list of essential readings – Foreign Policy

Shawn Brimley, one of the brains behind the QDR:. Trending Now Sponsored Links by Taboola. Sign up for free access to 3 articles per month and weekly email updates from expert policy analysts.