Was haben der benachbarte Pferdehof und der Junge Milan damit zu tun? Ostwind - Zusammen sind wir frei: Das Buch zum Film. In der dunkelsten Box des Pferdstalls findet sie den wilden und scheuen Hengst Ostwind. Sie spricht die Sprache der Pferde! Greg kann es einfach nicht fassen. Rupert hat eine Freundin! Seit dem Valentinsball ist er mit Abigail zusammen - und Greg ist ab sofort abgeschrieben. Der Schulweg zum Beispiel. Every one who has had the opportunity of making the comparison will remember that the effect produced on him by some witticisms is closely akin to the effect produced on him by subtle reasoning which lays open a fallacy or absurdity, and there are persons whose delight in such reasoning always manifests itself in laughter.

This affinity of wit with ratiocination is the more obvious in proportion as the species of wit is higher and deals less with less words and with superficialities than with the essential qualities of things. On the other hand, Humor, in its higher forms, and in proportion as it associates itself with the sympathetic emotions, continually passes into poetry: Some confusion as to the nature of Humor has been created by the fact that those who have written most eloquently on it have dwelt almost exclusively on its higher forms, and have defined humor in general as the sympathetic presentation of incongruous elements in human nature and life — a definition which only applies to its later development.

A great deal of humor may coexist with a great deal of barbarism, as we see in the Middle Ages; but the strongest flavor of the humor in such cases will come, not from sympathy, but more probably from triumphant egoism or intolerance; at best it will be the love of the ludicrous exhibiting itself in illustrations of successful cunning and of the lex talionis as in Reineke Fuchs , or shaking off in a holiday mood the yoke of a too exacting faith, as in the old Mysteries.

Again, it is impossible to deny a high degree of humor to many practical jokes, but no sympathetic nature can enjoy them. Strange as the genealogy may seem, the original parentage of that wonderful and delicious mixture of fun, fancy, philosophy, and feeling, which constitutes modern humor, was probably the cruel mockery of a savage at the writhings of a suffering enemy — such is the tendency of things toward the good and beautiful on this earth! Probably the reason why high culture demands more complete harmony with its moral sympathies in humor than in wit, is that humor is in its nature more prolix — that it has not the direct and irresistible force of wit.

Wit is an electric shock, which takes us by violence, quite independently of our predominant mental disposition; but humor approaches us more deliberately and leaves us masters of ourselves. Hence, too, it is, that while wit is perennial, humor is liable to become superannuated. As is usual with definitions and classifications, however, this distinction between wit and humor does not exactly represent the actual fact.

Like all other species, Wit and Humor overlap and blend with each other. A happy conjunction this, for wit is apt to be cold, and thin-lipped, and Mephistophelean in men who have no relish for humor, whose lungs do never crow like Chanticleer at fun and drollery; and broad-faced, rollicking humor needs the refining influence of wit. Indeed, it may be said that there is no really fine writing in which wit has not an implicit, if not an explicit, action. The wit may never rise to the surface, it may never flame out into a witticism; but it helps to give brightness and transparency, it warns off from flights and exaggerations which verge on the ridiculous — in every genre of writing it preserves a man from sinking into the genre ennuyeux.

And it is eminently needed for this office in humorous writing; for as humor has no limits imposed on it by its material, no law but its own exuberance, it is apt to become preposterous and wearisome unless checked by wit, which is the enemy of all monotony, of all lengthiness, of all exaggeration.

Perhaps the nearest approach Nature has given us to a complete analysis, in which wit is as thoroughly exhausted of humor as possible, and humor as bare as possible of wit, is in the typical Frenchman and the typical German. Voltaire, the intensest example of pure wit, fails in most of his fictions from his lack of humor. The sense of the ludicrous is continually defeated by disgust, and the scenes, instead of presenting us with an amusing or agreeable picture, are only the frame for a witticism. On the other hand, German humor generally shows no sense of measure, no instinctive tact; it is either floundering and clumsy as the antics of a leviathan, or laborious and interminable as a Lapland day, in which one loses all hope that the stars and quiet will ever come.

For this reason, Jean Paul, the greatest of German humorists, is unendurable to many readers, and frequently tiresome to all. Here, as elsewhere, the German shows the absence of that delicate perception, that sensibility to gradation, which is the essence of tact and taste, and the necessary concomitant of wit. All his subtlety is reserved for the region of metaphysics. He has the finest nose for Empirismus in philosophical doctrine, but the presence of more or less tobacco smoke in the air he breathes is imperceptible to him.

He has the same sort of insensibility to gradations in time. A German comedy is like a German sentence: We have heard Germans use the word Langeweile , the equivalent for ennui, and we have secretly wondered what it can be that produces ennui in a German. It is easy to see that this national deficiency in nicety of perception must have its effect on the national appreciation and exhibition of Humor. German facetiousness is seldom comic to foreigners, and an Englishman with a swelled cheek might take up Kladderadatsch , the German Punch, without any danger of agitating his facial muscles.

Indeed, it is a remarkable fact that, among the five great races concerned in modern civilization, the German race is the only one which, up to the present century, had contributed nothing classic to the common stock of European wit and humor; for Reineke Fuchs cannot be regarded as a peculiarly Teutonic product. But Germany had borne no great comic dramatist, no great satirist, and she has not yet repaired the omission; she had not even produced any humorist of a high order.

Among her great writers, Lessing is the one who is the most specifically witty. Of course we do not pretend to an exhaustive acquaintance with German literature; we not only admit — we are sure that it includes much comic writing of which we know nothing. We simply state the fact, that no German production of that kind, before the present century, ranked as European; a fact which does not, indeed, determine the amount of the national facetiousness, but which is quite decisive as to its quality.

Whatever may be the stock of fun which Germany yields for home consumption, she has provided little for the palate of other lands.

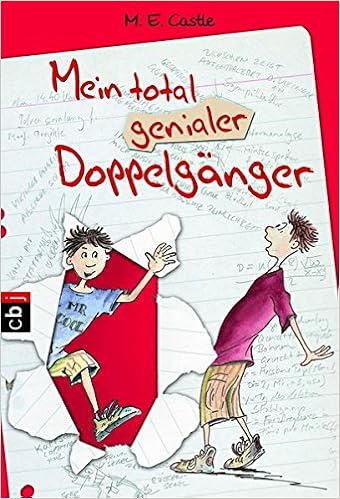

CASTLE - Definition and synonyms of Castle in the German dictionary

All honor to her for the still greater things she has done for us! She has fought the hardest fight for freedom of thought, has produced the grandest inventions, has made magnificent contributions to science, has given us some of the divinest poetry, and quite the divinest music in the world. No one reveres and treasures the products of the German mind more than we do. To say that that mind is not fertile in wit is only like saying that excellent wheat land is not rich pasture; to say that we do not enjoy German facetiousness is no more than to say that, though the horse is the finest of quadrupeds, we do not like him to lay his hoof playfully on our shoulder.

Still, as we have noticed that the pointless puns and stupid jocularity of the boy may ultimately be developed into the epigrammatic brilliancy and polished playfulness of the man; as we believe that racy wit and chastened delicate humor are inevitably the results of invigorated and refined mental activity, we can also believe that Germany will, one day, yield a crop of wits and humorists.

- Revelation: The Ancient Mysteries of the Sacred Secrets.

- Georges Revised Forecasts.

- Auswirkungen der Globalisierung auf Hamburg (German Edition)?

- Sonata No. 1 in A-flat Major - B-flat Clarinet - Clarinet in B-flat.

- In Free Fall by Juli Zeh?

Perhaps there is already an earnest of that future crop in the existence of Heinrich Heine, a German born with the present century, who, to Teutonic imagination, sensibility, and humor, adds an amount of esprit that would make him brilliant among the most brilliant of Frenchmen.

True, this unique German wit is half a Hebrew; but he and his ancestors spent their youth in German air, and were reared on Wurst and Sauerkraut , so that he is as much a German as a pheasant is an English bird, or a potato an Irish vegetable. But whatever else he may be, Heine is one of the most remarkable men of this age: He is, moreover, a suffering man, who, with all the highly-wrought sensibility of genius, has to endure terrible physical ills; and as such he calls forth more than an intellectual interest.

It is true, alas! The audacity of his occasional coarseness and personality is unparalleled in contemporary literature, and has hardly been exceeded by the license of former days. Hence, before his volumes are put within the reach of immature minds, there is need of a friendly penknife to exercise a strict censorship. Yet, when all coarseness, all scurrility, all Mephistophelean contempt for the reverent feelings of other men, is removed, there will be a plenteous remainder of exquisite poetry, of wit, humor, and just thought. It is apparently too often a congenial task to write severe words about the transgressions committed by men of genius, especially when the censor has the advantage of being himself a man of no genius, so that those transgressions seem to him quite gratuitous; he , forsooth, never lacerated any one by his wit, or gave irresistible piquancy to a coarse allusion, and his indignation is not mitigated by any knowledge of the temptation that lies in transcendent power.

We are also apt to measure what a gifted man has done by our arbitrary conception of what he might have done, rather than by a comparison of his actual doings with our own or those of other ordinary men. We make ourselves overzealous agents of heaven, and demand that our brother should bring usurious interest for his five Talents, forgetting that it is less easy to manage five Talents than two. Whatever benefit there may be in denouncing the evil, it is after all more edifying, and certainly more cheering, to appreciate the good. Hence, in endeavoring to give our readers some account of Heine and his works, we shall not dwell lengthily on his failings; we shall not hold the candle up to dusty, vermin-haunted corners, but let the light fall as much as possible on the nobler and more attractive details.

Those of our readers who happen to know nothing of Heine will in this way be making their acquaintance with the writer while they are learning the outline of his career. We have said that Heine was born with the present century; but this statement is not precise, for we learn that, according to his certificate of baptism, he was born December 12th, We shall quote from these in butterfly fashion, sipping a little nectar here and there, without regard to any strict order:.

Believe me, I yesterday heard some one utter folly which, in anno , lay in a bunch of grapes I then saw growing on the Johannisberg. Among them, many of whom my mother says, that it would be better if they were still living; for example, my grandfather and my uncle, the old Herr von Geldern and the young Herr von Geldern, both such celebrated doctors, who saved so many men from death, and yet must die themselves.

And the pious Ursula, who carried me in her arms when I was a child, also lies buried there and a rosebush grows on her grave; she loved the scent of roses so well in life, and her heart was pure rose-incense and goodness. The knowing old Canon, too, lies buried there. Heavens, what an object he looked when I last saw him! He was made up of nothing but mind and plasters , and nevertheless studied day and night, as if he were alarmed lest the worms should find an idea too little in his head.

And the little William lies there, and for this I am to blame. The kitten lived to a good old age. It was dismal weather; yet the lean tailor, Kilian, stood in his nankeen jacket which he usually wore only in the house, and his blue worsted stockings hung down so that his naked legs peeped out mournfully, and his thin lips trembled while he muttered the announcement to himself. And an old soldier read rather louder, and at many a word a crystal tear trickled down to his brave old mustache.

It is strangely touching to see an old man like that, with faded uniform and scarred face, weep so bitterly all of a sudden. While we were reading, the electoral arms were taken down from the Town Hall; everything had such a desolate air, that it was as if an eclipse of the sun were expected. I knew what I knew; I was not to be persuaded, but went crying to bed, and in the night dreamed that the world was at an end. And a great deal of this came very conveniently for me in after life.

For if I had not known the Roman kings by heart, it would subsequently have been quite indifferent to me whether Niebuhr had proved or had not proved that they never really existed. And with arithmetic it was still worse. What I understood best was subtraction, for that has a very practical rule: As for Latin, you have no idea, madam, what a complicated affair it is. The Romans would never have found time to conquer the world if they had first had to learn Latin. Luckily for them, they already knew in their cradles what nouns have their accusative in im. I, on the contrary, had to learn them by heart in the sweat of my brow; nevertheless, it is fortunate for me that I know them.

Of Greek I will not say a word, I should get too much irritated. The monks in the Middle Ages were not so far wrong when they maintained that Greek was an invention of the devil. God knows the suffering I endured over it. He was at first destined for a mercantile life, but Nature declared too strongly against this plan. I very early discerned that bankers would one day be the rulers of the world. He had already published some poems in the corner of a newspaper, and among them was one on Napoleon, the object of his youthful enthusiasm. This poem, he says in a letter to St.

Translation of «Castle» into 25 languages

Lectures on history and literature, we are told, were more diligently attended than lectures on law. He had taken care, too, to furnish his trunk with abundant editions of the poets, and the poet he especially studied at that time was Byron. The tragic collision lies in the conflict between natural affection and the deadly hatred of religion and of race — in the sacrifice of youthful lovers to the strife between Moor and Spaniard, Moslem and Christian. Some of the situations are striking, and there are passages of considerable poetic merit; but the characters are little more than shadowy vehicles for the poetry, and there is a want of clearness and probability in the structure.

It was published two years later, in company with another tragedy, in one act, called William Ratcliffe , in which there is rather a feeble use of the Scotch second-sight after the manner of the Fate in the Greek tragedy. We smile to find Heine saying of his tragedies, in a letter to a friend soon after their publication: Paganini interrupted him thus: He there pursued his omission of law studies, and at the end of three months he was rusticated for a breach of the laws against duelling.

While there, he had attempted a negotiation with Brockhaus for the printing of a volume of poems, and had endured the first ordeal of lovers and poets — a refusal. According to his friend F. In this minority was Elise von Hohenhausen, who proclaimed Heine as the Byron of Germany; but her opinion was met with much head-shaking and opposition. We can imagine how precious was such a recognition as hers to the young poet, then only two or three and twenty, and with by no means an impressive personality for superficial eyes.

Perhaps even the deep-sighted were far from detecting in that small, blonde, pale young man, with quiet, gentle manners, the latent powers of ridicule and sarcasm — the terrible talons that were one day to be thrust out from the velvet paw of the young leopard. It was apparently during this residence in Berlin that Heine united himself with the Lutheran Church. He would willingly, like many of his friends, he tells us, have remained free from all ecclesiastical ties if the authorities there had not forbidden residence in Prussia, and especially in Berlin, to every one who did not belong to one of the positive religions recognized by the State.

At the same period, too, Heine became acquainted with Hegel. I never was an abstract thinker, and I accepted the synthesis of the Hegelian doctrine without demanding any proof; since its consequences flattered my vanity. I was young and proud, and it pleased my vainglory when I learned from Hegel that the true God was not, as my grandmother believed, the God who lives in heaven, but myself here upon earth. This foolish pride had not in the least a pernicious influence on my feelings; on the contrary, it heightened these to the pitch of heroism.

I was at that time so lavish in generosity and self-sacrifice that I must assuredly have eclipsed the most brilliant deeds of those good bourgeois of virtue who acted merely from a sense of duty, and simply obeyed the laws of morality.

See a Problem?

The reader will see that he does not neglect an opportunity of giving a sarcastic lash or two, in passing, to Meyerbeer, for whose music he has a great contempt. I believe he wished not to be understood; and hence his practice of sprinkling his discourse with modifying parentheses; hence, perhaps, his preference for persons of whom he knew that they did not understand him, and to whom he all the more willingly granted the honor of his familiar acquaintance.

Thus every one in Berlin wondered at the intimate companionship of the profound Hegel with the late Heinrich Beer, a brother of Giacomo Meyerbeer, who is universally known by his reputation, and who has been celebrated by the cleverest journalists. The equally witty and gifted Felix Mendelssohn once sought to explain this phenomenon, by maintaining that Hegel did not understand Heinrich Beer. I now believe, however, that the real ground of that intimacy consisted in this — Hegel was convinced that no word of what he said was understood by Heinrich Beer; and he could therefore, in his presence, give himself up to all the intellectual outpourings of the moment.

One beautiful starlight evening we stood together at the window, and I, a young man of one-and-twenty, having just had a good dinner and finished my coffee, spoke with enthusiasm of the stars, and called them the habitations of the departed. The stars are only a brilliant leprosy on the face of the heavens. Notwithstanding this emphatically Protestant grounding, Jonson maintained an interest in Catholic doctrine throughout his adult life and, at a particularly perilous time while a religious war with Spain was widely expected and persecution of Catholics was intensifying, he converted to the faith.

Jonson's biographer Ian Donaldson is among those who suggest that the conversion was instigated by Father Thomas Wright, a Jesuit priest who had resigned from the order over his acceptance of Queen Elizabeth's right to rule in England. Conviction, and certainly not expedience alone, sustained Jonson's faith during the troublesome twelve years he remained a Catholic. His stance received attention beyond the low-level intolerance to which most followers of that faith were exposed. The first draft of his play Sejanus was banned for " popery ", and did not re-appear until some offending passages were cut.

His habit was to slip outside during the sacrament, a common routine at the time—indeed it was one followed by the royal consort, Queen Anne , herself—to show political loyalty while not offending the conscience. In May Henry IV of France was assassinated, purportedly in the name of the Pope; he had been a Catholic monarch respected in England for tolerance towards Protestants, and his murder seems to have been the immediate cause of Jonson's decision to rejoin the Church of England.

Jonson's productivity began to decline in the s, but he remained well known. However, a series of setbacks drained his strength and damaged his reputation. He resumed writing regular plays in the s, but these are not considered among his best. They are of significant interest, however, for their portrayal of Charles I 's England. The Staple of News , for example, offers a remarkable look at the earliest stage of English journalism.

The lukewarm reception given that play was, however, nothing compared to the dismal failure of The New Inn ; the cold reception given this play prompted Jonson to write a poem condemning his audience the Ode to Myself , which in turn prompted Thomas Carew , one of the "Tribe of Ben," to respond in a poem that asks Jonson to recognise his own decline. The principal factor in Jonson's partial eclipse was, however, the death of James and the accession of King Charles I in Jonson felt neglected by the new court.

A decisive quarrel with Jones harmed his career as a writer of court masques, although he continued to entertain the court on an irregular basis. For his part, Charles displayed a certain degree of care for the great poet of his father's day: Despite the strokes that he suffered in the s, Jonson continued to write. At his death in he seems to have been working on another play, The Sad Shepherd.

Though only two acts are extant, this represents a remarkable new direction for Jonson: During the early s he also conducted a correspondence with James Howell , who warned him about disfavour at court in the wake of his dispute with Jones. Jonson died on or around 16 August , and his funeral was held the next day.

It was attended by 'all or the greatest part of the nobility then in town'. Another theory suggests that the tribute came from William Davenant , Jonson's successor as Poet Laureate and card-playing companion of Young , as the same phrase appears on Davenant's nearby gravestone, but essayist Leigh Hunt contends that Davenant's wording represented no more than Young's coinage, cheaply re-used. It has been claimed that the inscription could be read "Orare Ben Jonson" pray for Ben Jonson , possibly in an allusion to Jonson's acceptance of Catholic doctrine during his lifetime although he had returned to the Church of England but the carving shows a distinct space between "O" and "rare".

It includes a portrait medallion and the same inscription as on the gravestone. It seems Jonson was to have had a monument erected by subscription soon after his death but the English Civil War intervened. Apart from two tragedies, Sejanus and Catiline , that largely failed to impress Renaissance audiences, Jonson's work for the public theatres was in comedy. These plays vary in some respects. The minor early plays, particularly those written for boy players , present somewhat looser plots and less-developed characters than those written later, for adult companies.

Already in the plays which were his salvos in the Poet's War, he displays the keen eye for absurdity and hypocrisy that marks his best-known plays; in these early efforts, however, plot mostly takes second place to variety of incident and comic set-pieces. They are, also, notably ill-tempered.

Thomas Davies called Poetaster "a contemptible mixture of the serio-comic, where the names of Augustus Caesar , Maecenas , Virgil , Horace , Ovid and Tibullus , are all sacrificed upon the altar of private resentment". Another early comedy in a different vein, The Case is Altered , is markedly similar to Shakespeare's romantic comedies in its foreign setting, emphasis on genial wit and love-plot. Henslowe's diary indicates that Jonson had a hand in numerous other plays, including many in genres such as English history with which he is not otherwise associated.

The comedies of his middle career, from Eastward Hoe to The Devil Is an Ass are for the most part city comedy , with a London setting, themes of trickery and money, and a distinct moral ambiguity, despite Jonson's professed aim in the Prologue to Volpone to "mix profit with your pleasure". His late plays or " dotages ", particularly The Magnetic Lady and The Sad Shepherd , exhibit signs of an accommodation with the romantic tendencies of Elizabethan comedy. Within this general progression, however, Jonson's comic style remained constant and easily recognisable. He announces his programme in the prologue to the folio version of Every Man in His Humour: He planned to write comedies that revived the classical premises of Elizabethan dramatic theory—or rather, since all but the loosest English comedies could claim some descent from Plautus and Terence , he intended to apply those premises with rigour.

He set his plays in contemporary settings, peopled them with recognisable types, and set them to actions that, if not strictly realistic, involved everyday motives such as greed and jealousy. In accordance with the temper of his age, he was often so broad in his characterisation that many of his most famous scenes border on the farcical as William Congreve , for example, judged Epicoene. He was more diligent in adhering to the classical unities than many of his peers—although as Margaret Cavendish noted, the unity of action in the major comedies was rather compromised by Jonson's abundance of incident.

To this classical model Jonson applied the two features of his style which save his classical imitations from mere pedantry: Coleridge, for instance, claimed that The Alchemist had one of the three most perfect plots in literature. Jonson's poetry, like his drama, is informed by his classical learning. Some of his better-known poems are close translations of Greek or Roman models; all display the careful attention to form and style that often came naturally to those trained in classics in the humanist manner. Jonson largely avoided the debates about rhyme and meter that had consumed Elizabethan classicists such as Thomas Campion and Gabriel Harvey.

Accepting both rhyme and stress, Jonson used them to mimic the classical qualities of simplicity, restraint and precision. The epigrams explore various attitudes, most from the satiric stock of the day: Although it is included among the epigrams, " On My First Sonne " is neither satirical nor very short; the poem, intensely personal and deeply felt, typifies a genre that would come to be called "lyric poetry.

A few other so-called epigrams share this quality. Jonson's poems of "The Forest" also appeared in the first folio. Underwood , published in the expanded folio of , is a larger and more heterogeneous group of poems. It contains A Celebration of Charis , Jonson's most extended effort at love poetry; various religious pieces; encomiastic poems including the poem to Shakespeare and a sonnet on Mary Wroth ; the Execration against Vulcan and others.

The volume also contains three elegies which have often been ascribed to Donne one of them appeared in Donne's posthumous collected poems. There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with Shakespeare , some of which may be true. Drummond also reported Jonson as saying that Shakespeare "wanted art" i. Whether Drummond is viewed as accurate or not, the comments fit well with Jonson's well-known theories about literature.

In "De Shakespeare Nostrat" in Timber , which was published posthumously and reflects his lifetime of practical experience, Jonson offers a fuller and more conciliatory comment. He recalls being told by certain actors that Shakespeare never blotted i. His own claimed response was "Would he had blotted a thousand! Thomas Fuller relates stories of Jonson and Shakespeare engaging in debates in the Mermaid Tavern ; Fuller imagines conversations in which Shakespeare would run rings around the more learned but more ponderous Jonson.

That the two men knew each other personally is beyond doubt, not only because of the tone of Jonson's references to him but because Shakespeare's company produced a number of Jonson's plays, at least two of which Every Man in His Humour and Sejanus His Fall Shakespeare certainly acted in. However, it is now impossible to tell how much personal communication they had, and tales of their friendship cannot be substantiated. Jonson's most influential and revealing commentary on Shakespeare is the second of the two poems that he contributed to the prefatory verse that opens Shakespeare's First Folio.

William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us" , did a good deal to create the traditional view of Shakespeare as a poet who, despite "small Latine, and lesse Greeke", [48] had a natural genius. The poem has traditionally been thought to exemplify the contrast which Jonson perceived between himself, the disciplined and erudite classicist, scornful of ignorance and sceptical of the masses, and Shakespeare, represented in the poem as a kind of natural wonder whose genius was not subject to any rules except those of the audiences for which he wrote.

But the poem itself qualifies this view:. Some view this elegy as a conventional exercise, but others see it as a heartfelt tribute to the "Sweet Swan of Avon", the "Soul of the Age! Jonson was a towering literary figure, and his influence was enormous for he has been described as 'One of the most vigorous minds that ever added to the strength of English literature'.

Theater von Schiller Erster Theil 1810 Original-Scan (German Edition)

John Aubrey wrote of Jonson in " Brief Lives. In the Romantic era, Jonson suffered the fate of being unfairly compared and contrasted to Shakespeare, as the taste for Jonson's type of satirical comedy decreased. Jonson was at times greatly appreciated by the Romantics, but overall he was denigrated for not writing in a Shakespearean vein.

In , after more than two decades of research, Cambridge University Press published the first new edition of Jonson's complete works for 60 years. Bentley notes in Shakespeare and Jonson: Their Reputations in the Seventeenth Century Compared , Jonson's reputation was in some respects equal to Shakespeare's in the 17th century.

After the English theatres were reopened on the Restoration of Charles II , Jonson's work, along with Shakespeare's and Fletcher 's, formed the initial core of the Restoration repertory. It was not until after that Shakespeare's plays ordinarily in heavily revised forms were more frequently performed than those of his Renaissance contemporaries. Many critics since the 18th century have ranked Jonson below only Shakespeare among English Renaissance dramatists. Critical judgment has tended to emphasise the very qualities that Jonson himself lauds in his prefaces, in Timber , and in his scattered prefaces and dedications: For some critics, the temptation to contrast Jonson representing art or craft with Shakespeare representing nature, or untutored genius has seemed natural; Jonson himself may be said to have initiated this interpretation in the second folio, and Samuel Butler drew the same comparison in his commonplace book later in the century.

At the Restoration, this sensed difference became a kind of critical dogma. But "artifice" was in the 17th century almost synonymous with "art"; Jonson, for instance, used "artificer" as a synonym for "artist" Discoveries, Nicholas Rowe , to whom may be traced the legend that Jonson owed the production of Every Man in his Humour to Shakespeare's intercession, likewise attributed Jonson's excellence to learning, which did not raise him quite to the level of genius.