This was particularly common among the servants of the great fur companies, not only because few white women cared to take up their tot with the rovers of the wide fur-countries, but that it was also a matter of policy to ingratiate themselves with the powerful Indian tribes among whom they were thrown. So sons and daughters were born to the Macs and. Pierres; and the blood of Indian warriors, mingling with that of " Hieland lairds'; and French bourgeois, the traders, the trappers, and the voyageurs of the great Fur Company, began to flow in a steady stream all through I His Majesty's Plantations in North America,' deepening and expanding until it reached from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from York Factory to Fort Victoria.

Young officers, knowing this, proceeded accordingly. We were speaking of the 1 Half-breed " as an interested party in the feud between the rival trading Companies. He was, in truth, an influential factor in the struggle. At the time of ' oo which we write the j Metis" were almost entirely of French extraction, and were exclusively in the employ of the North- West Company. At a later date, on the Hudson Bay Company beginning to trade in the south, its officers formed liasons with the young women of the various tribes, and an English, in contradistinction to a French half-breed race, in process of time sprung up.

As yet, as we have said however, the Half-breed was of French descent and owned his allegiance to the Canadian Company. To that Company he naturally looked for employment; and he took to its service not only with alacrity but with ancestral pride. For his duties he was admirably fitted ; for the Half-breed possesses, in addition to the Frenchman's versatility and ready resource, the Indian's skill as a canoeist and his intuitive knowledge of the woods.

This was true, indeed, not only of the Half-breed, but of the full-blooded Indian. To the French, both were drawn bv characteristics of race, which found no counter- part in the English. The French race was quick to merge into the Indian, and to pick up the habits, and not infrequently the vices, of the dusky children of the woods. Parkman, the historian, remarks that the French colonists of Canada held, from the beginning, a peculiar intimacy of relation with the Indian tribes.

- Maria di Magdala (Italian Edition)?

- John MacLean (MacLean, John, ) | The Online Books Page;

- The Warden of the Plains, and Other Stories of Life in the Canadian North-west.

- Navigation menu;

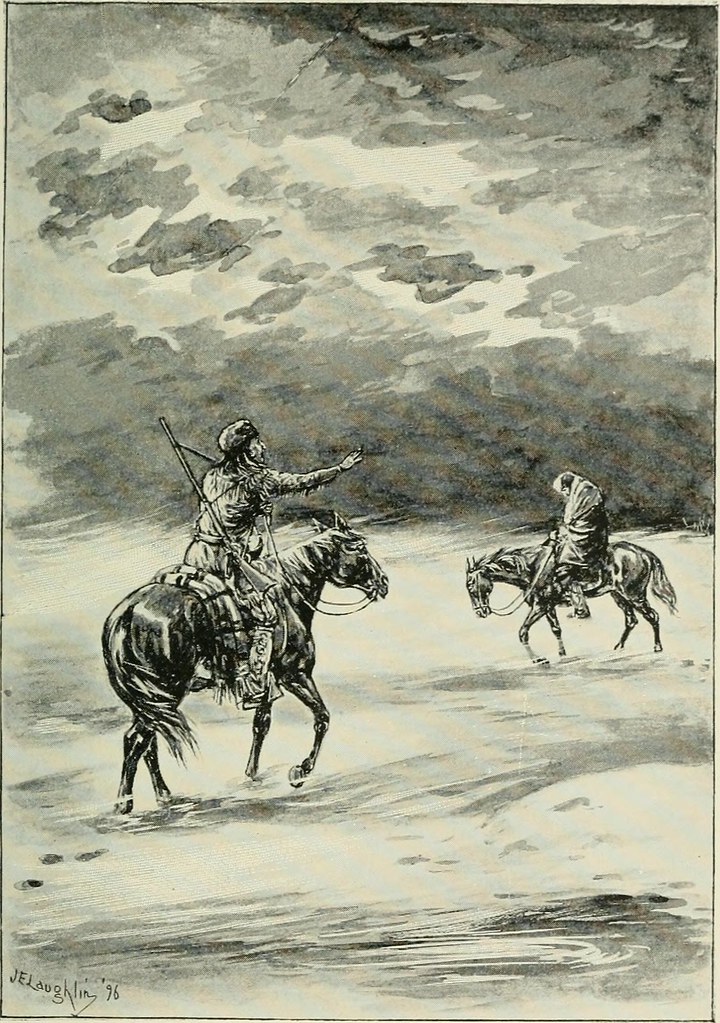

- Image from page of "The warden of the plains, and othe… | Flickr!

He is speaking specially of the period of French military domination in the colony: Her agents were busy in every village, studying the language of the inmates, complying with their usages, flattering their prejudices, caressing them, cajoling them, and whispering friendly warnings in their ears against the wicked designs of the English. When o o o a party of Indian chiefs visited a French fort, they were greeted with the firing of cannon and rolling of drums ; they were regaled at the tables of the officers, and bribed with medals and decorations, scarlet uniforms, and French flags.

Far wiser than their rivals, the French never ruffled the self-complacent dignity of their guests, never insulted their religious notions, nor ridiculed their ancient customs. They met the savage half way, and showed an abundant readiness to mould their own features after his likeness. Count Frontenac himself, plumed and painted like an Indian chief, danced the war-dance and yelled the war-song at the camp-fires of his delighted allies. In its efforts to win the friendship and alliance of the Indian tribes, the French Government found every advantage in the peculiar character of its subjects—that pliant and plastic temper which forms so marked a contrast to the stubborn spirit of the Englishman.

Hundreds betook themselves to the forest never to return. These overflowings of French civilisation were merged in the waste of o o barbarism, as a river is lost in the sands of the desert. The wandering Frenchman chose a wife or a concubine among his Indian friends; and, in a few generations, scarcely a tribe of the west was free from an infusion of Celtic blood. The French Empire in America could exhibit among its subjects every- shade of colour from white to red, every gradation of culture, from the highest civilisation of Paris to the rudest barbarism of the wigwam.

In many a squalid camp among the plains and forests of the west, the traveller would have encountered men owning the blood and speaking the language of France, yet, in their swarthy visages and barbarous costume, seeming more akin to those with whom they had cast their lot. The renegade of civilisation caught the habits and o o imbibed the prejudices of his chosen associates. He loved to decorate his long hair with eagle feathers, to make his face hideous with vermilion, ochre, and soot, and to adorn his greasy hunting frock with horse-hair fringes.

His dwelling, if he had one, was a wigwam. He lounged on a bear-skin while his squaw boiled his venison and lighted his pipe. In hunting, in dancing, in singing, in taking a scalp, he rivalled the genuine Indian. His mind was tinctured with the superstitions of the forest. This class of men is not yet extinct. Parkman draws a characteristic picture of the Canadian woodsman, in contrast with the sturdy English colonist, whose political and religious life developed a type quite different from the easy-going French-Canadian, the product of feudalism and Mother-Church.

The warden of the plains, and other stories of life in the Canadian Northwest

Says this interesting writer: Buoyant and gay, like his ancestry of France, he made the frozen wilderness ring with merriment, answered the surly howling of the pine forest with peals of laughter, and warmed with revelry the groaning ice of the St. Careless and thoughtless, he lived happy in the midst of poverty, content if he could but gain the means to fill his tobacco-pouch, and decorate the cap of his mistress with a ribbon. The example of a beggared nobility, who, proud and penniless, could only assert their rank by idleness and ostentation, was not lost upon him.

A rightful heir to French bravery and French restlessness, he had an eager love of wandering and adventure; and this propensity found ample scope in the service of the fur-trade, the engrossing occupation and chief source of income to the colony. When the priest of St. Anne's had shrived him of his sins; when, after the parting carousal, he embarked with his comrades in the deep-laden canoe; when their oars kept time to the measured cadence of their song, and the blue, sunny bosom of the Ottawa opened before them; when their frail bark quivered among the milky foam and black rocks of the rapid ; and when, around their camp-fire, they wasted half the night with jests and laughter,—then the Canadian was in his element.

His footsteps explored the farthest hiding-places of the wilderness. In the evening dance, his red cap mingled with the scalp-locks and feathers of the Indian braves; or, stretched on a bear-skin by the side of his dusky mistress, he watched the gambols of his hybrid offspring, in happy oblivion of the partner whom he left unnumbered leagues behind.

The fur-trade engendered a peculiar class of restless bush-rangers, more akin Me north-west fur Company. Those who had once felt the fascinations of the forest were unfitted ever after for a life of quiet labour; and with this spirit the whole colony of Canada was infected. For a time no other race or class of men could have been more serviceable to the Company. They wTere inured to hardships; theyT wTere at home in the woods; their relations with the Indians wTere of the happiest; and they were never home-sick, or out of humour with their surroundings.

Furthermore, they were always loyal to the Company. With zest did they enter into the feuds between it and its rival, and with equal zest did they take up their masters' unfortunate quarfel with Lord Selkirk and his colony. This nobleman's settlement on the Red River was, naturally enough, considered an usurpation, for he had acquired his rights by purchase from the Hudson Bayr Company, who had neither discovered the region nor had been in occupancy.

Special offers and product promotions

On the other hand, the North-West traders were the discoverers, and for many years had been in possession. In a dispassionate review of the facts, it is important that this should be borne in mind. The Conquest may be said to have given the English a right to the territory; but in the absence of any confirmation of its charter, subsequent to that occurrence, it can hardly be said to have transferred that right to the Hudson Bay Company. It is important also to note that the discoverers were not unauthorised adventurers.

French trading operations were always coupled with the motive of discovery. It was the invariable policy of the French Government, through its representatives at Quebec, to encourage geographical research and advance the possessions of the Crown.

North-West Mounted Police - Wikipedia

As early as the year , M. By this and the enterprises which immediately followed it, the whole vast interior, as far west as the Rocky Mountains, became known to the French; and in the region they speedily established their forts. In , they erected Fort St. In , all the district of the Assiniboine was within the area of their operations, and Fort La Reine, on the St.

Charles, and Fort Bourbon, on the Riviere des Biches, were established. Five years later, the Verandryes took possession of the Upper Mississippi and ascended the Saskatchewan in the interest of French trade. In , the famous post of Michillimackinac, at the entrance of the Lac des Illinois Michigan , was established. Other parts of the continent were also covered by the operations of the French traders and discoverers. Hudson Bay had early been reached by way of the Saguenay and Lake St. John, by the Ottawa, and by Lakes Nipigon and Winnipeg. The Kaministiquia, at the head of Lake Superior, as we have seen, was the base of supplies for operations in the west, and the great rallying-place of the French trader and voyageur.

In short, the wThole country was probed and made known to the outer world by the enterprise of the French and the French Canadians. As a consequence, any maps of the interior that were at all trustworthy were those of the French: Hence the opposition to the assumptions of the Hudson Bay Company, and the hostile rivalry which it engendered. After the Conquest, it is true, the French for a time abandoned their western possessions; but the old trading habit returned, stimulated, as we have seen, by the sturdy Scotch and the organization of the Canadian " Nor'-Westers.

It had, however, its periods of trade depression and its years of disaster. Another year, there would be great floods in the west, and trade would be impeded if not wholly lost. Then there came the era of strife with the Red River colony and collision with the 1 Hudson Bays.

For a time hostilities were keen and continuous, and on both sides ruinous. This coalition of the Nor'-Westers with its English rival gave great strength to the united Company. It brought it an accession of capable traders and intelligent voyageurs and discoverers. In the service of the North-West Company were men—Alexander Mackenzie and David Thompson among the number—whose names will be forever identified with discovery in the North- West. It was in those days that young Washington Irving was their guest, when he made his memor- O O O ' able journey to Montreal.

The agents who presided over the affairs of the Company at headquarters were very important personages indeed, as might be expected. They were veterans that had grown grev in the wilds, and were full of all the O O. They were, in fact, a sort of commercial aristocracy in Quebec and Montreal, in days when nearly everybody- was more or less directly interested in the fur trade. As the passage admirably describes a gathering at the annual conference of the Company at Fort William, we make no excuse for its insertion here, and with it shall conclude the present chapter.

Here two or three of the leading partners from Montreal proceeded once a year to meet the partners from the various trading-places in the wilderness, to discuss the affairs of the Company during the preceding year, and to arrange plans for the future. On these occasions might be seen the change since the unceremonious times of the old French traders, with their roystering coureurs de bois.

Now the aristocratic character of the Briton, or rather the feudal spirit of the Highlander, shone out magnificently ; every partner who had charge of an interior post, and had a score of retainers at his command, felt like the chieftain of a Highland clan, and was almost as important in the eyes of his dependants as of himself.

- Dona Guidinha do Poço (Ilustrado) (Literatura Língua Portuguesa) (Portuguese Edition)?

- John MacLean!

- Similar Books!

- Download This eBook!

- Onion Rings: The Ultimate Recipe Guide;

- Seeing Jesus.

To him a visit to the grand conference at Fort William was a most important event, and he repaired thither as to a meeting of Parliament. The partners from Montreal, however, were the lords of the ascendant. Coming from the midst of a luxurious and ostentatious life, they quite eclipsed their compeers from the woods, whose forms and faces had been battered by hard living and rough service, and whose garments and equipments were all the worse for wear.

Indeed the partners from below considered the whole dignity of the Company as represented in their own persons, and conducted themselves in suitable style. They ascended the rivers in great state, like sovereigns making a. They were wrapped in rich furs, their huge canoes freighted with every convenience and luxury, and manned by Canadian voyageurs as obedient as clansmen. They carried with them cooks and bakers, together with delicacies of every kind, and abundance of choice wines for the banquets which attended this great convocation.

Fort William, the scene of this important meeting, was a considerable village on the banks of Lake Superior. Here, in an immense wooden building, was the great council-chamber, and also the banquet- ing-hall, decorated with Indian arms and accoutrements, and the trophies of the fur trade. The house swarmed at this time with traders and voyageurs from Montreal bound to the interior posts, and some from the interior posts bound to Montreal. The councils were held in great state, for every member felt as if sitting in Parliament, and every retainer and dependant looked up to the assemblage with awe, as to the House of Lords.

There was a vast deal of solemn deliberation and hard Scottish reasoning, with an occasional swell of pompous declamation. These grave and weighty councils were alternated with huge feasts and revels. The tables in the great o o banqueting-room groaned under the weight of game of all kinds,—of venison from the woods, and fish from the lakes ; with hunters' delicacies, such as buffaloes' tongues and beavers' tails ; and various luxuries from Montreal.

There was no stint of generous wine, for it was a hard-diinking period, a time of loyal toasts and Bacchanalian songs and brimming bumpers. While the chiefs thus revelled in the hall, and made the rafters resound with bursts of loyalty and old Scottish song, chanted in voices cracked and sharpened by the Northern blast, their merriment was echoed and prolonged by a mongrel legion of retainers, Canadian voyageurs, half-breeds, Indian hunters, and vagabond hangers-on, who feasted sumptuously without, on the crumbs from their table, and made the welkin ring with old French ditties, mingled with Indian yelps and veilings.

To a trading corporation this was a foolish proviso. We have seen that the Company took no thought to colonise its possessions: The aid it gave to discovery, if we except some little assistance to the expeditions to the Arctic Seas in search of Franklin, was very slight. It sought solely its own interests. If it opened up regions in the North-West, it was to establish a trading-post, not to set up a meteorological station or erect an observatory. We doubt if its administrative officers could give, even approximately, the latitude and longitude of any one of its stations.

Many of its traders and voyageurs doubtless, in time, became very familiar with the North-West, but only a few of them caught the adventurous spirit of the old navigators and travellers, and forgot their trading operations in their eagerness to explore the country. From the earliest period of colonial settlement at Quebec, the French led the van in all exploratory effort.

Quebec was but the gateway to the Far West. From its portal the Jesuit was the first to lead off in the adventurous mission of carrying the Cross into the Canadian wilderness. Closely following the Black Robes, Champlain pursued his toilsome journey, by the Ottawa and Lake Nipissing, to the inland sea of the Hurons.

Mary's river and Lake Superior. Later on, Marquette tracked the mighty waters of Superior, and penetrated to the Mississippi. Down this great artery La Salle carried the flewr de lis to the Gulf of Mexico, and finally found an unknown grave in Texas. From the beginning of the seventeenth century the adventurous spirits of old France were to be found on all the great waters of the continent; and the footsteps of French traders, guided, it may be, by an Algonquin Indian, might be traced on the crisp snow of even the western prairie.

Over the latter, in , the Verandryes, father and son, braved their course to the far Rockies, through untold dangers and over almost insurmountable obstacles. War was not long in following on the trail of the explorer. Over the route taken by Joliet and Marquette to the west might be seen the armed column of Rogers' Rangers, on its way to the fort at Detroit. English garrisons were also to be found o o at Sault Ste. Marie, and at Green Bay, on Lake Michigan. Ere long the woods at Mackinaw resounded with the shrieks of Pontiac's victims in the treacherously captured garrison of Michillimackinac; while a storm of blood and fire was passing over the region between Lake Erie and the Alleghanies.

For a time exploration held its breath while the continent was thrilled with the shock of battle at Quebec. We have mentioned the tragedy enacted at Michillimackinac, the result of the' "conspiracy of Pontiac," whom Parkman terms the " Satan of the forest paradise. Some extracts from this trader's narrative of the occurrence, Mr. Parkman weaves into his own history of the Indian war after the Conquest. Hemy's narrative is replete with interest, not only for the thrilling personal account he gives of the Ojib- way surprise and massacre of the English garrison, but for its record of trading operations in Western Canada, and in the Indian territories beyond the Red River.

In August, , while as yet there had been no treaty of peace between the English and the Indians who had taken part with the French against the conquerors of the country, Henry decided to set out on a trading expedition from Montreal to Mackinaw, at the entrance to Lake Michigan. Receiving permission from General Gage, who was then Commander-in-Chief in Canada, and providing himself with a passport from the town major, he left Montreal on the 2nd of August, and Lachine on the following day.

His party followed the usual route to the west, by the Ottawa and Lake Nipissing. By the end of the month, Henry had entered the Georgian Bay, and early in September, he reached the island of Michillimackinac, sometimes called the " Great Turtle. But Henry disregarded this advice, for the place was important to him in preparing his outfit for trade in the North-West; though he took the precaution to cross the straits of Mackinaw and enter the Fort.

The Fort at this time was garrisoned by a small number of militia, who, having families, as Henry tells us, became less soldiers than settlers. Not a few of them had served in the French army; at the Conquest they entered the service and accepted the pay of Britain. Henrv was informed that the whole band of Chippeways from the neighbouring island of Michillimackinae intended to pay him a visit, a piece of information which was far from agreeable to the adventurous trader.

The report was true. Here is Henry's account of the unwelcome visit: They walked in single file, each with his tomahawk in one hand and scalping-knife in the other. Their bodies were naked from the waist upward, except in a few instances, where blankets were thrown loosely over the shoulders. Some had feathers thrust through their noses, and their heads decorated with the same. It is unnecessary to dwell on the sensations with which I beheld the approach of this uncouth, if not frightful, assemblage.

I demand your attention! Englishman, it is your people that have made war with our father, the French king. You are his enemy ; and how, then, could you have the boldness to venture among us his children? You know that his enemies are ours. Englishman, although you have conquered the French, you have not c II. We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods and mountains, were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance; and we will part with them to none.

In this warfare many of them have been killed; and it is our custom to retaliate, until such time as the spirits of the slain are satisfied. But the spirits of the slain are to be satisfied in either of two ways: This is done by making presents. It was his trading outfit, not his life, that was most in danger. You do not come armed, with an intention to make war; you come in peace, to trade with us, and supply us with necessaries, of which we are much in want. We shall regard you, therefore, as a brother; and you may sleep tranquilly without fear of the Chippeways.

As a token of our friendship, we present you with this pipe to smoke. It was not his life, but his goods, they wanted. There is a delightful naivete about the chief's speech, in his remarks about the giving of presents, a hint which Henry was slow to take, though he reluctantly acceded to a later request that the delegation should be allowred to taste his English " milk," i.

Henry's relief from this visitation Was but the prelude, however, to another. No sooner were the Chippeways gone than two hundred of the neighbouring tribe of the Ottawas, from L'Arbre Croche, came out of Lake Michigan and drew their canoes up on the beach. They had heard of the arrival of the Englishman, Henry, and his trading expedition.

The Ottawas, unlike the Ojibways, manifested no nice sense of delicacy in their overtures to the trader; nor in their demands did they beat about the bush. They summoned Henry to appear before them, and without any preliminary palaver informed him of their object in coming to the Fort. Their demand was that Henry and the other traders who had come to Michillimack- inac should distribute, on credit, to each of the tribes merchandise and ammunition to the amount of fifty beaver-skins, the value of the goods to be repaid the traders on the return next summer of the Indians from their winter hunts.

The demand was refused, as the Ottawas were known to be "bad pay;' but it was threateningly renewed, and the traders were given twenty-four hours for reflection. The next day there was a Council; but Henry and his party thought it safest not to be present, though a message was sent asking that the amount of the credit demanded might be reduced. This was not entertained ; and threats of death were returned by the messenger should their demands not be complied with. That night news fortunately reached the small garrison of the near approach of some men of the 60th Regiment, who had been sent from Detroit on detachment duty at Michiliimackinac and the other posts in the west.

For the next two years he seems to have spent the time alternately at the I Soo" and at Mackinaw. At the close of the year , the post at the " Soo 1 was accidentally burned, and Henry informs us, that to obtain suitable shelter, and save themselves from famine, the garrison and the traders withdrew to Mackinaw.

During the winter, rumours were rife of hostile designs against the English soldiery at Michillimackinac. The garrison at this time, according to Henry, consisted of ninety privates, two subalterns, and the Commandant. There seems to be doubt, however, of the accuracy of this statement. Parkman, who quotes from the letters of Captain Etherington, the Commandant of the Fort, gives the number of rank and file as thirty-five, exclusive of officers, traders, and non-combatants. The trader, Henry, was again an inmate of the Fort. Spring passed without incident, save an increasing restlessness among the Chippeways Ojibways of the district.

To this little heed was paid by the deluded garrison. The Indians, indeed, were allowed to come to the Fort to buy from the traders knives and tomahawks. Henry, alone, seems to have been apprehensive. An Indian, named Wawatam, had taken a great liking ' ' o o to him, and imparted to him his fears for the safety of Henry and the garrison. This Heniy communicated to Etherington, the Commandant, but the latter onlv laughed at the trader's uneasiness.

The Indians, he affirmed, were friendly, and to emphasise this, he added, that the Chippeways were on the morrow to play a game of baggattaway lacrossej with a band of the Sac Indians from Wisconsin. The morrow was the 4th of June, the birthday of King George. Here is Parkman's account of what happened on that anniversary: Women and children were moving about the doors; knots of Canadian voyageurs reclined on the ground, smoking and conversing; soldiers were lounging listlessly at the doors and windows of the barracks, or strolling in careless undress about the area.

The gates were wide open, and soldiers were collected in groups under the shadow of the palisades, watching the Indian ball-play. Most of them were without arms, and mingled among them were a great number of Canadians, while a multitude of Indian squaws, wrapped in blankets, were conspicuous in the crowd. Indian chiefs and warriors were also among the spectators, intent, apparently, on watching the game, but with thoughts, in fact, far otherwise employed.

I The plain in front was covered by the ball-players. The game in which they were engaged, called baggattaway by the Ojibways, is still, as it always has been, a favourite with many Indian tribes. At either extremity of the ground, a tall post was planted, marking the stations of the rival parties. The object of each was to defend its own post, and drive the ball to that of its adversary. Hundreds of lithe and agile figures were leaping and bounding upon the plain.

Each was nearly naked, his loose black hair flving in the wind, and each bore in his hand a bat of a form peculiar to this game. At one moment the whole were crowded together, a dense throng of combatants, all struggling for the ball; at the next, they were scattered again, and running over the ground like hounds in full cry. Each, in his excitement, yelled and shouted at the top of his voice.

Rushing and striking, tripping their adversaries, or hurHng them to the ground, they pursued the animating congest amid the laughter and applause of the spectators. This was no chance stroke. It was part of a preconcerted stratagem to ensure the surprise and destruction of the garrison. In a moment they had reached it. The amazed English had no time to think or act. The shrill cries of the ball-players were changed to the ferocious war-whoop.

The wrarriors snatched from the squaws the hatchets, which the latter, with this design, had concealed beneath their blankets. Some of the Indians assailed the spectators without, while others rushed into the fort, and all was carnage and confusion, At the outset, several strong hands had fastened their gripe upon Etherington and Leslie, and led them awav from the scene of the massacre towards the woods.

Within the area of the fort, the men were slaughtered without mercy! Presently the Indian war-cry reached his ears, and going to the window, he says: I had in the room in which I was a fowling-piece, loaded with swan-shot. This I immediately seized, and held it for a few minutes, waiting to hear the drum beat to arms. In this dreadful interval, I saw several of my countrymen fall, and more than one struggling between the knees of an Indian, who, holding him in this manner, scalped him while yet living, At length, disappointed in the hope of seeing resistance made to the enemy, and sensible, of course, that no effort of my own unassisted arm could avail against four hundred Indians, I thought only of seeking shelter.

But its owner, a M. Langlade, refused to succour Henry, being unfriendly to the English, and disliking Henry as a rival in trade. Fortunately, a Pawnee slave of the Frenchman showed our trader the humanity which her master had withheld, and conducted him to a place of hiding. Here he was subsequently discovered, but though his life was spared, he was subjected to every horror, and taken from one place of confrnement to another.

For some time, he tells us, his only covering was an old shirt; his bed was the bare ground ; and for days he was left without food. In one passage he says: They had a loaf which they cut with the same knives they had used in the massacre—knives still covered with blood. The blood they moistened with spittle, and, rubbing it on the bread, offered this for food to their prisoners, telling them to eat the blood of their countrymen.

To the friendship of the Indian, Wawatam, who interceded with the chief of the Ojibways for his life and personal safety, Henry owed his release from his savage captors. Painted and attired as an Indian, he spent the following winter with his rescuer on the north shore of Lake Huron. The remainder of the English prisoners were rescued by the Ottawas, of Lake Michigan, a neighbouring tribe who being incensed at the Chippeways' attack on Michillimackinac without having been asked to participate in it, wished to deprive them of some of the glory of the victory, and induced their captors to give up the soldiers and traders still in their possession.

These the Ottawas took to Montreal, and received a ransom for them on their arrival, in August, Henry, in the summer of the following year, had the opportunity, of which he gladly availed himself, to accompany a party of the Chippeways, of Sault Ste. Marie, who were setting out for Niagara, to which place they had been summoned by Sir William Johnson, for the purpose of entering into a treaty of peace with Great Britain. At Niagara, Henry joined an army, consisting of some three thousand men, under General Bradstreet, who were about to proceed to Detroit, to raise Pontiac's siege of that fort, which, for over a year, had been gallantly defended by Major Gladwyn, its commandant.

In the spring of , we find him again at Sault Ste. Marie, pursuing his trading operations as far west as Michipicoten, on Lake Superior. Here, for a number of years, he was engaged in mining and prospecting, while at intervals he continued his fur-trade with the Indians. His success in the latter seems to have been great, for he writes, that in June, , he left the Sault on his first trading expedition to the head of Lake Superior " with goods and provisions to the value of three thousand pounds sterling, on board twelve small canoes and four large ones.

Like most travellers of the period, Henry never fails to omit some description of the tribes among whom for a time he sojourned, and of the social customs that prevail amongst them. Here are a few extracts from his narrative, chiefly concerning the female Cree: The men were almost entirely naked, and their bodies painted with a red ochre, procured in the mountains.

Their ears were pierced, and filled with the bones of fish and of land animals. The skin is painted, or else ornamented, with beads of various colours. The rolls, with their coverings, resemble a pair of large horns. Their clothing is of leather, or dressed skins of the wild ox and the elk. The dress, falling from the shoulders to below the knee, is of one entire piece.

Girls of an early age wear their dresses shorter than those more advanced. The same garment covers the shoulders and the bosom; and is fastened by a strap, which passes over the shoulders; it is confined about the wraist by a girdle. The stockings are of leather, made in the fashion of leggings. This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations.

Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity individual or corporate has a copyright on the body of the work. As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public.

We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant. Would you like to tell us about a lower price? If you are a seller for this product, would you like to suggest updates through seller support?

Read more Read less. Here's how restrictions apply. Wentworth Press August 27, Language: Be the first to review this item Would you like to tell us about a lower price? I'd like to read this book on Kindle Don't have a Kindle? Share your thoughts with other customers. Why will it be an important work for both the Celtic community and the non-Celtic community?

It will be a film that will both celebrate our Celtic part of our heritage. So many people left from both Scotland and Ireland to seek fame and fortune and a new life in the New World and this film will portray one of the many success stories of such a venture. This movie is a Scottish and Manitoba production about a hero that is highly respected and celebrated in Manitoba and is a hero in waiting to Scots. So many key people in history take their place in this amazing true story: McGillivray was the most powerful man in the fur trade, and was a family friend of long standing. The children moved to Montreal in , and Cuthbert and James were placed under the control of another fur magnate, John Stuart, a cousin of Donald A.

Stuart, carrying out the directions left in the will of the late Cuthbert Grant, had the boys baptized in the Presbyterian Church. They were then sent back to Scotland to be educated in the manner of the British Aristocracy. James remained in Scotland but Cuthbert returned to Montreal when he was sixteen years old. When will it be released, and where? We hope to start filming in Manitoba end of July with a release date in Canada and Scotland sometime in as well as worldwide release.

I am deeply interested in this..

Is it a film now? I was only recently able to fill in my fam native lines…and, wow! Those lines are crazy!