Lynn Peter Lyon Peyton V. Lyons Oliver Lyttelton Charles B. Peter Magrath William Mahan B. Malmstrom Dumas Malone Ruth M. Maxwell Gavin Maxwell Robert S. Mayberry Anne Maybury Adrian C. Gerald McMurtry Robert H. Meaney Florence Crannell Means W. Melby Seymour Melman A.

Mencken Heinrich Meng Frank G. Meyer Barlow Meyers Jack D. Micaud Michelangelo James A.

- The Worthing Saga.

- Douze Études: For Piano Solo (Kalmus Edition)!

- Kiss Me If You Can - 2 (Versione Italiana ) PDF Kindle - CairoYancy;

- International Relations: Which grand theory best describes the world today? Why?!

- ;

- .

- !

DeWitt Miller Robert W. Milne George Milne Lorus J. Misra Gladys Mitchell Harold P. Wayne Morgan John T. Morgan 2 Kenneth O. Morrison 2 Penelope Mortimer Henry W. Morton Miriam Morton Philip E. Muller Steven Muller William F. Mullin Nolie Mumey Helen W. Naipaul Louise Nalbandian O. Nambiar Joseph Milton Nance B. Nathan Robert Nathan K.

Blair Neatby Martin C. Nef Charles Neider Stephen C. Nelson Jack Nelson James G. Nesbit Evaline Ness Arthur H. Nichols Ben Nicholson Donald M. Nicol Reinhold Niebuhr Glenn A. Nineham Edna Nixon Lucille M. Noel Hans Nogly Richard H. Nolte Max Nomad Abdul G. Norton Frederick Nossal Alan E. Nourse Paul Novick Walter T.

Nyholm Edgar O'Ballance C. Orban George Ordish Frederick I. Outland Michael Ovenden Bonaro W. Northcote Parkinson Ethelyn M. Parry Pius Parsch Nels A. Pearson Hesketh Pearson Jane H. Pease Robin Pedley William R. Peters Bryan Peters Heinz F. Petrishcheva Eugene Petrov Walter V. Phillips Peter Philp Dorothy M. Pickles Josephine Piekarz Richard A. Plamenatz Valdine Plasmati Raye R. Gunther Plaut Georgi Plekhanov M. Pleshkin George Plimpton J. Plumb Gladys Plummer Forrest C. Polsby Charlotte Pomerantz Gerald M.

Pomper Lynn Poole Maurice A. Pope Karl Popper Arthur T. Porter Eliot Porter J. Prescott John Press A. Prest William Preston A. Grenfell Price Charles A. Protter Wilhelm Prueller Paul W. Pruyser Roy Pryce Frederic L. Pusey Sergei Pushkarev Lucian W. Raphael Armin Rappaport Jesse E. Rawson Man Ray Verne F. Reese James Reeves Herbert W. Reichert Ed Reid James M. Reynolds Mack Reynolds Maynard C.

Riasanovsky Aquilino Ribeiro Charles E. Richardson Mordecai Richler Robert W. Roberts Gene Roberts James L. Roberts Jane Roberts Frank C. Robinson Earl Robinson Helen M. Preston Robinson Richard D. Robinson Trevor Robinson Stefan H. Rolo Jose Luis Romero C. Rosecrance Raymond Roseliep Seymour M. Rosenau Art Rosenbaum Edward W. Roucek Berton Roueche J. Russett Kent Ruth A. Salant Tuty Saleh B. Saletore Herman Salinger J. Scalapino Jack Schaefer Edward H.

Schafer Adam Schaff George B. Schapiro Betty Schechter Joseph B. Schiffer Selma Schiffer Theron F. Schlabach Willi Schlamm John T. Schumann Philippa Schuyler Arnold T. Seldin Peter Self Ben B. Semyonov Maurice Sendak Ramon J. Sensenig Victor Serge R. Shipton Eric Shipton M. Shotwell Paul Showers Marshall D. Sigmund Irwin Silber George A. Silver Shel Silverstein Don C. Simckes Georges Simenon S. Singh Khushwant Singh D. Smith Eugene Randolph Smith G. Snyder Hyman Sobiloff Donald J.

Sobol Edward Sofen Reidar F. Sorokin Gavin Souter Richard W. Spencer Stephen Spender Joseph J. Spinage Natalie Davis Spingarn L. Stansby Walter Starkie Theofanis G. Swearer Irving Swerdlow Louis J. Tibbutt Paul Tillett Nannie M. Tilley Paul Tillich James H. Toklas John Toland J. Paul Torrance Stephen E. Udall Dorothy Uhnak Adam B. Upfield Willard Uphaus L. Varg Jose Vasconcelos Harold G.

Vatter Beatrice Vaughan J. Veatch Helen Vendler E. Warren Wagar Edward C. Lloyd Warner Fintan B. Watkins Colin Watson J. Steven Watson Richard A. Montgomery Watt Ben J. Wehrli Jerome Weidman Walter F. West Jerry West Morris L. West Nathanael West Vincent I. West Wallace West H. Westlake Christine Weston Theodore L. Westow Nathaniel Weyl Burton K.

White Lionel White Morton G. White Don Whitehead Andrew G. Whitton Leonard Wibberley W. Wilber Richard Wilbur Francis O. Dover Wilson James Q. Wilson John Wilson Mitchell A. Wilson Sloan Wilson Norman B. Wolf Bernard Wolfe Bertram D. Woods Sara Woods G. Xydis Yigael Yadin K. William Zartman Theodora S.

Article Authors of Filter? Fixx Haskel Frankel John G. Lewis George Lichtheim Frank S. Albright Austen Albu John R. Altman Frank Altschul Peter H. Ameringer Kingsley Amis A. Anderson Karen Anderson Odin W. Armstrong Richard Armstrong Charles W. Arnade Peter Arno Thurman W. Arnold Raymond Aron Alfred G. Boone Atkinson James D. Austin Michael Avallone Walter R. Averett Albert Axelbank R.

Backus Martha Bacon Ben H. Bahmer George Bailey Kenneth K. Bailey Tom Bailey W. Bainton Carl Bakal Donald W. Baker Dorothy Baker J. Roger Baker Maury Baker R. Baldwin James Baldwin John W. Banfield William Bankier Philip C. Bannister Amiri Baraka Paul A. Baran Bernard Barber Elinor G. Barber Rowland Barber Willard F. Barger Loren Baritz William C. Bastin Darrell Bates H. Jack Bauer John J. Bauke Gregory Baum Franklin L. Baur Lee Baxandall C. Bayley John Bayley D. Bazelon Stewart Beach Vincent W.

Beagle Dick Beamish George D. Bechhoefer Ann Beck Curt F. Beech John Beecher John H. Beer Max Beerbohm Wilton G. Begley Brendan Behan L. Benenson Jaime Benitez Howard F. Berger John Berger Thomas G. Berkes Theodore Berland Adolf A. Bernstein Daniel Berrigan N. Best Alfred Bester Ernesto F. Black Hillel Black Susan M.

Bork David Boroff Merle L. Bouwsma Ben Bova J. David Bowen Robert O. Boyer Francis Boylan L. Brent Bozell George D. Bretnor Robert Breuer W. Brice Carl Bridenbaugh Ellis O. Brown Alan Brown B. Frank Brown Claude Brown D. Mackenzie Brown Delmer M. Brown Ivor Brown James F.

Brown Wenzell Brown Henry J. Brucker Gerard Bruckner I. Buck Desmond Buckle Priscilla L. Burke Hans Burkhardt Ardath W. Butler Henry Butler Jeffrey E. Campbell Mildred Campbell Robert W. Cane Melville Cane Erwin D. Caravan Manoel Cardozo Jane P. Carey Oscar Cargill William G. Carroll Hayden Carruth Clarence B. Childers Gilbert Chinard Elizabeth R. Christian Agatha Christie Trevor L.

Church Creighton Churchill Winston S. Churchill Irina Chymanovsky Charles E. Clark Colin Clark Duncan C. Clarke Dale Clarke George L. George Classen Lucius D. Clemens Hal Clement Robert J. Clements Harlan Cleveland James L. Clifford Mike Clifford William C. Clough Gladys Cluff W. Cochran Eric Cochrane Edwin B. Coddington Warren Coffey Florence D. Cohen Margaret Cohen Stanley E. Cohen Lawrence Cohn Margaret L. Collier John Collier C. Collins Archibald Colquhoun Joel G.

Colton Padraic Colum C. Costello Giovanni Costigan Robert C. Cotts John Coulson L. Gray Cowan Raymond G. Cremin Ollinger Crenshaw O. David Cronon Alexander L. Cunningham George Cuomo Thomas F. Michael Curtis Carl T. Curtis Helena Curtis K. Marshall Curtiss Cyril Cusack G. Davies Christopher Davis Douglas M. Davis Ernie Davis Harold E. Dean Mary Dean Herbert A. Dellin Gladys Delmas Charles F. Dempsey Nigel Dennis F. Detwiler Richard Deutch John C. Diamond Stanley Diamond Philip K. Dougherty George Doughty William O. Kamil Dziewanowski Ernest P. Eddy Maurice Edelman J. Edmondson Dagmar Edqvist John T.

Ehrmann Sarel Eimerl Loren C. Chandler Elliott Humphry F. Ethan Ellis Leo R. Esty William Esty R. Stanton Evsn John C. Eyerman Gertrude Ezorsky Emil L. Fadiman John Edwin Fagg N. James Ferguson George V. Ferguson Irene Ferguson Wallace K. Fiedler Andrew Field G. Lowell Field Mark G.

Finney Janet Fiscalini Walter J. Fish Morris Fishbein Edgar J. Flint Fletcher Flora Michael T. Forbes Enzo Forcella Franklin L. Ford Jesse Hill Ford C. Frantz Conon Fraser Lindley M. Freedman Morris Freedman Frank M. Freeman Otto Frei George H. Freitag Anne Fremantle Paul A. Frye Dean Frye William R. Fuller John Fuller G. Keith Funston Philip N. Gaines Sarah Gainham Henry C. Galant Marc Galanter Catherine A. Gallagher Paul Gallico Pierre M. Gardner Robert Gardner Edward T. Gargan Charles Garrett Henry E.

Garthoff Romain Gary Zygmunt J. Giesey Guy Giffen Sidney F. Gilford Thomas Gillespie J. Gleason Burt Glinn David M. Glixon Rumer Godden B. Goldman Lawrence Goldman Marshall I. Goldman Rene Goldman Robert P. Goodavage Eugene Goodheart John I. Goodman Ralph Goodman David L. Gordon David Gordon H. Scott Gordon Harold J. Steele Gow James A. Graff Frank Graham J. Desmond Greaves Percy L. Greene Jerry Greene Norvin R. Greever Andy Gregg A. Gruening Leo Gruliow Kenneth W. Gwyn Andrew Gyorgy Charles M.

Hale Alex Haley James A. Haley Babette Hall Daniel G. Duncan Hall James R. Hall Tim Hall Louis J. Harrison Harry Harrison John A. Hartsook George Hartung Donald J. Hauberg Jerzy Hauptmann Rita E. Hauser Iola Haverstick Nathan A. Hayes Lincoln Haynes Rhys W. Hays Max Hayward John N. Heathorn Herbert Heaton Fred M. Heinlein Jack Heinz Rae C. Heiple Sidney Heitman Virginia P. Leon Helguera Walter W. Herring Jeannine Herron Christian A. Hibben Ben Hibbs Edwin P. Higgins John Higham Robin D.

Hirsch Phil Hirsch Robert S. Hirschfield Joseph Hitrec Philip K. Hoare Cecil Hobbs John A. Hobson Wilder Hobson Edward D. Hoch Joe Hochderffer William E. Hodges Godfrey Hodgson Francis P. Hoeber Barry Hoffman Daniel N. Warren Hollister Anselm Hollo J. Hoyt Elbert Hubbard P. Hugh-Jones Catharine Hughes D. Hughes Daniel Hughes Everett C. Hunter Tom Hunter William H.

Huntington Robert Huntzinger Denis E. Hurwitz Maude Hutchins Robert M. Isaacs Harold Isbell C. Turrentine Jackson Hayes B. Jaffe John Jakes Francis G. James Martin Janicke Andrew C. Jarrett Robert Jastrow Frank A. Jellison Christopher Jencks H. Jenkins Roy Jenkins Will F. Michael Jenkinson William A. Johnson Edgar Johnson Edgar N. Jones Jenkin Lloyd Jones L. Louis Joughin Jean T. Kalb Nicholas Kaldor Arthur D. Kaledin Ray Kalfus A. Kameny Max Kaminsky I. Kennan Edwin Kennebeck John F.

Kennedy Hugh Kenner Frank L. Kershner Heinz Kersten T. Kibel Robert Kiely James R. Kilpatrick Martin Kilson Young C. Kirstein Lincoln Kirstein Israel M.

Kittleson Carolyn Kizer Herbert E. Arthur Klein Philip S. Knapp William Knapp Damon F. Kolehmainen Costas Koliyannis Edward A. Kolom Hans Koning William A. Kunstler Herbert Kupferberg Stephen G. Kurtz Dan Kurzman Robert E. Langfield Edwin Lanham Richard A. Lash Marghanita Laski A. Victor Lasky Melvin J. Lassner Earl Latham Rebecca H. Lawrence Merloyd Lawrence Robert Z. Legters Colin Legum Stanford E. Leopold Warren Lerner B. Leshem Shane Leslie Simon O. Lesser Doris Lessing T. Lethbridge William Letwin William E.

Lewis Bernard Lewis C. David Lewis William H. Lidin Laurence Lieberman A. Lindsay Jack Lindsay John V. Lindsay Almont Lindsey Paul M. Linebarger William Lineberry Dwight L. Littlefield David Littlejohn James T. Lockerbie Marius Lodeesen Martin B. Loeb Lili Loebl Ralph E. The architecture used i s severe and powerful.

The figures themselves are given the attitude of noble, dignified beings. The clothes they are wearing axe simple, but heavy and distinctive. Anything partaking of the vulgar or the low is cast aside. They stand easily and move freely but with calm and dignity. Their gestures, no matter how vitalized, are at the same time measured and restrained. They remain in control of their emotions even in the most dramatic cases.

Their behaviour in any situation i s the one of true aristocrats. It i s such an interest in v i t a l i t y , broken free, which partly led to the advent of the Baroque. It i s interesting to observe how Michelangelo succeeded in maintaining such a s p i r i t in his Sistine Ceiling. The solid grounding of the Seers and Ignudi already pointed out greatly contributes to keep the bursting energy within controllable bounds. We also observe that the passionate figures of the Prophets are answered by the calm figures of the Sibyls and that the active Ignudi count among them some solemnly calm ones such as the one above Jeremiah.

The figure of God himself, bursting with boundless vigour in the Creation of the Sun and Moon, i s given less impetus 24 in the nearby scene Separation of the Earth and Waters and a solemn calm although i t i s sweeping down in the s t i l l next one the Creation of Adam. Now in classic art in general, the subject-matter usually lends i t s e l f f a i r l y easily to a conciliation of Monumentality and v i t a l i t y.

Trouble begins to develop when an animated drama such as the Expulsion of Heliodorus has to be depicted. The classic a r t i s t , here, in his w i l l to impose on the event both Monumentality and a strongly pulsating l i f e of i t s own, i s faced with the problem of suffusing the work with dramatic v i t a l i t y which can easily run wild while keeping the latter within the solemn frame of Monumentality.

We shall see later how Raphael reached an "impasse" in the Expulsion of Heliodorus and how in the tapestry cartoons he evolved the perfect solution to this problem. Francis belong to such a group. Now sadness is another quality which con-f l i c t s with Monumentality, for as just said above i t implies a certain departure from the calm and the controlled, and can 25 easily develop into an exaggerated sentimentalism. Heze too, thus, the classic artist was faced with a problem. Giotto had understood that problem and in his Lamentation Padova, Arena Chapel; ca. The Death of St.

Francis in Santa Croce Bardi Chapel; ca. Faced with the same problem, Michelangelo in his early Pieta Rome, St. Fra Bartolommeo's Pieta Florence, P i t t i ; ca. Summarizing our results, we can say that the tr i p l e imposi-tion on the event of an intense force of presence, of a powerful v i t a l i t y and of the solemn s p i r i t of the Chefren defined as 13 Monumentality constituted the major aim of the classic a r t i s t.

The whole of classic painting, indeed, could perhaps be summed up as a series of attempts to bring these three elements into a happy unity. Towards that end and this could be called the practical side of the classic w i l l , the classic artist endeavoured 14 to intensely exploit a l l the pos s i b i l i t i e s of the formal elements and to interrelate the latter within a powerful unity. The event depicted here i s the waking up of P e t e r by the angel.

And somehow we get the mysterious f e e l i n g t h a t they could wake up at any time. Thus Raphael confronts us here w i t h 27 a situation where a conflict between the supernatural and the natural i s imminent and could arise at any moment. Needless to say that the pulse of the dramatic event taking place i s thereby greatly intensified. The xeadex may notice especially how the daxk form of the soldiex holding a toxch xises dramatically and energetically on the whole length of the brighter stairs, and how the silhouette of his companion also affirms i t s e l f impressively against the distant bare landscape.

He may also observe how the fact that we cannot see their faces gives a more o f f i c i a l "cachet" to the action of these two soldiers by affirming in a purer way the authority which they personify, and how this fact directly contributes to the monumentality of the whole by making the event look more o f f i c i a l and more formal. He may observe, f i n a l l y , the outstanding nobility and grandeur of pose in the sleeping soldier on the extreme right, how light, especially, unifies the three scenes, and how Raphael makes the two massive piers contribute, through their colossal scale, to the monumen-t a l i t y intended, and, through their "glowing", to the dramatic l i f e of the whole.

This work indeed, especially when we take into account the stringent economy of means practised, realizes, within the event which i t f a i t h f u l l y and powerfully brings out, one of the happiest dynamic combinations of Monumentality and dramatic 29 v i t a l i t y ever achieved.

For t h i s reason, i t can be included without h e s i t a t i o n among the very few greatest masterpieces of the c l a s s i c w i l l. The event taking place, here, has nothing of a drama; i t can be described as r a t i o n a l thinking being done, Reason at work or s t i l l i n t e l l e c t u a l i t y i n process.

The idea was to i l l u s t r a t e t h i s a c t i v i t y using a group of outstanding philosophers from Antiquity, among whom Plato and A r i s t o t l e. In agreement with the c l a s s i c w i l l , Raphael proceeds to monumentalize the scene.

He sets the figures i n an a r c h i t e c t u r a l context at once powerful and majestuousi the monumental arches recede with order and solemnity i n the distance. The figures themselves are given "noble" proportions; t h e i r gestures are clear and controlled and t h e i r attitude breathes calm and d i g n i t y. Beside conferring Monumentality to the event, the a r c h i -tecture i s also made expressive of the very a c t i v i t y depicted: The pavement i n the foreground f u l f i l l s the same function: Now by depicting the philosophers in the middle of an animated discussion, Raphael at once communicates a certain v i t a l i t y to the event i t s e l f.

In agreement with the c l a s s i c 30 w i l l , Raphael wishes to intensify this v i t a l i t y. To this end, he f i r s t proceeds to organically relate the architecture with the figures. This i s accomplished f i r s t by suffusing the figures with such a v i t a l i t y , distributing and interrelating them in such a way, and using such a system of coloring on them. This i s greatly helped by the placing of some figures inside the border of the space of the arches, and by the fact that the space of the arches i s connected with the foreground space, independently of the figures, through per-spective.

What results i s a truly organic interpenetration of the vast space created by the arches with the space inhabited by the figures. Now Raphael distributes and interrelates the figures in such a way that the eye i s led implacably to the two philosophers in the center this i s greatly helped by the placing of the latter exactly in the opening of the last arch. By thus doing Raphael is making a l l the amounts of intellectual v i t a l i t y present in the scattered figures especially in the foreground converge towards the figures of Plato and Aristotle and contribute 31 their own share to the v i t a l i t y already present in those too.

Similarly, the qualities inherent to the architecture find themselves dynamically concentrated and integrated in those two figures and not only juxtaposed, as would be the case i f there was no organic or dynamic relationship between the figures and the architecture. As a result of a l l this concentration of energy on Plato and Aristotle, the l i f e of the mind which they eminently symbolize i s presented to us suffused with a powerful v i t a l i t y.

Here again, like in the Liberation of Peter, the event has been not only monumentalized but powerfully vitalized. The activity i s essentially: Inaagreement with the classic w i l l , Raphael's intention i s to suffuse i t with a powerful v i t a l i t y. Like he was to do in the Liberation of Peter the year after, he chooses to depict the moment most pregnant with dramatic tension, when the angels are just about to f a l l on Heliodorus.

Now the wide space between the two groups in the foreground disregarding the papal group had to be activated with dramatic v i t a l i t y , and to this end Raphael made the group of women and children, on the l e f t , r e c o i l violently. It i s with a similar intention of charging the air through-out with dramatic tension that Raphael devised such an archi-tecture as he did: We can also see why Raphael included the two figures climbjLng up on one of the columns: Similarly for the two men standing against that 33 column and talking to each other: On the drama thus powerfully vitalized, Raphael was faced with the problem of imposing Monumentality.

The papal group on the l e f t serves such a purpose. It may also be observed how the impenitent Heliodorus preserves a dignity of bearing in the c r i t i c a l situation he finds himself i n. The massive architecture also throws a note of severity. But a l l the same, we feel here an unresolved conflict between dramatic v i t a l i t y on the one hand and Monumentality on the other hand. The papal group i s not integrated in the event but merely juxtaposed; the architecture, for a l l i t s massiveness, does not resolve in repose and majesty.

Now I would like the reader to realize the d i f f i c u l t y which Raphael was encountering in the treatment of this subject as compared with the School of Athens. In both depictions, the space defined i s wide and deep and the figures occupy a rather small proportion of i t. In the School of Athens, as we have seen, space i s energized but in a gentle and controlled way, let us say, in agreement with the event taking place. In the Expulsion on the contrary, Raphael had to devise ways to pervade space not only with v i t a l i t y but with dramatic v i t a l i t y since the event i s a true drama , i f the specific event taking place was to be truly enlivened.

The logical solution was to increase the scale and the power of expression of the figures and reduce the importance given to and the role played by space and architecture. In the Death of Ananias, for instance, the figures are contained in such a shallow space that there i s no need for a complicated architecture to impose the sense of drama intended. The energy released in the foreground i s not allowed to be dispersed but immediately reaches the group of apostles, on which i t i s at once reflected and amplified.

The apostles thus f u l f i l l the dual function of imposing Monumentality on the event to a powerful degree by the solemnity of their presence and of acting as a human sounding board for the dramatic energy released in the foreground. Monumentality and dramatic v i t a l i t y are thus not f e l t as conflicting like in the Expulsion but as integrated into a powerful unity. John the Baptist Florence, Scalzo; One may notice here how effectively the calm and solemn figure in the l e f t foreground answers Herod's dramatic movement foreward although the latter i s addressed to the Baptist , and how the enclosing of the actors in a shallow space allows the event to vibrate with Monumentality and dramatic v i t a l i t y , both being powerfully unified.

It was stated earlier that classic art solved the traditional conflict between Spir i t u a l i t y and Natural L i f e. Now such a conflict, in the Quattrocento, existed in two forms. Artists could purposely dehumanize the human form in order to emphasize the idea of the supernatural as Botticelli, for instance, so often did — in which case the conflict was between Natural Life and S p i r i t u a l i t y.

On the other hand, they could depict the holy figures as simple, down-to-earth people, aiming essentially at a convincing natur-alism — in which case a conflict existed between Natural Life and the internal S p i r i t u a l i t y of the work by challenging our conception of holy figures. By powerfully affirming the dignity of Nature as we have seen the classic work automatically integrates Natural Life in f u l l and vice-versa. On the other hand, the higher level of existence at once more v i t a l and more monumental to which the classic a r t i s t raised reality, became the equivalent for a spiritualized existence.

- .

- !

- Publication - The Unz Review;

The religious classic work of art thus theoretically breathes both Natural Life and Spiri t u a l i t y internal and external no longer f e l t as conflicting, but as conciliated. Michelangelo grounded his Prophets and Ignudi in the Sistine Ceiling so powerfully to their seat partly because he rightly gathered that the suggestion of any lose detachment of these figures from their seat, when seen from below, would make them look half-seated, half-suspended in the air, thus challenging our sense of gravity. And this could not be tolerated by the classic w i l l operating in him.

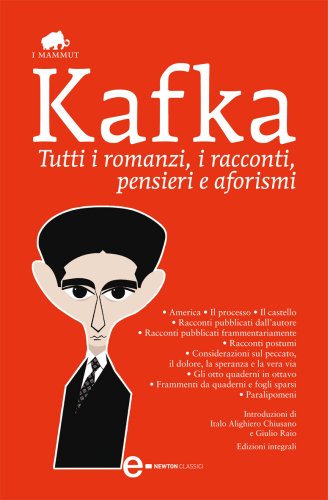

Ebook Epub Download Gratis Il Castello Enewton Classici Italian Edition Chm

New York, , p. It i s important that we realize how the dignity of Nature i s respected by the classic a r t i s t. The latter achieves in his works a v i t a l i t y often greater than i s found in real l i f e , yet through the respect of the physical premises enumerated above, Nature i s always f u l l y integrated. That i s why although the world created by the classic a r t i s t may be highly superior to ours, yet we would feel more at home in i t than in any of the Quattrocento worlds: It i s irrelevant to our discussion that pre-Socratic and Hellenistic period philosophers appear side-by-side in the School of Athens.

What matters i s that they are depicted as i f l i v i n g at the same epoch. The dating and attribution of this as well as of the other works assigned in this essay to Giotto, are taken from C. For a contestation of these matters, see M. Meiss, Giotto and As s i s i. W81fflin observes that na bourgeois art i s transformed into an aristocratic one which adopts the distinctive c r i t e r i a of demeanour and feeling prevalent among the upper classes.

Although he imposes here a powerful monumentality on the event, yet he f a i l s to dynamize i t s existence and we have the clear impression that a l l the activity going on has been "frozen". These three elements indeed a l l contribute to one another. They have been considered separately here in order to enable us to better grasp the mechanism with which the classic w i l l i s fundamentally operating.

By formal elements I mean essentially here space, light, color and architecture as well as the human figure i t s e l f. In his Liberation of Peter Rome, S. The comparison of the two works i s taken from Wolfflin, op. Wolfflin observes that the Liberation of Peter " i s perhaps better fitted than any other of Raphael's works to lead the hesitant to a f u l l appreciation of him.

Press, , I, p. For a description of this system of coloring, see Freedberg op. It i s demonstrated here how Raphael makes use of the assertive and recessive "personality" of the different hues to activate space. Freedberg observes that the space occupied by the figures i s transformed into a "plastically responsive aether" ibid.

The idea of "interpenetration" i s taken from Freedberg, op. The Funeral of St. The increase in scale which his figures gradually under-went can be partly interpreted as a search for such a solution. In the Liberation of Peter, as we have seen, Raphael achieved a similar integration. It may also be observed that the force of presence of the event has greatly gained in the Cartoons. In a work such as the Expulsion, the eye i s attracted certainly to the main actors, but also to the architecture and wide space around.

The latter are indeed pervaded with drama, but in doing so we somewhat lose nation of the specific drama being played. In the Cartoons, the event confronts us with a most powerful intensity of presence. In the latter works, indeed, as in the Liberation of Peter. Raphael struck what i s perhaps the ideal balance between force of presence, v i t a l i t y and Monumentality.

This example i s taken from Wolfflin, op. Andrea, on the other hand, created his two masterpieces: In a l l these works we recognize the classic w i l l as we defined i t in the preceding chapter as unmistakably as in the works discussed above. By a rather unusual coincidence, since the classicizing o trend was overwhelmingly predominating, those years also saw the emergence of a new art which was soon to powerfully challenge the accepted ideals.

This new art, which we shall study in the works of Pontormo and Rosso, has proven to be one of the most controversial ones which art history has dealt with in the last forty years. It i s my intention to help throw some light on i t s true character and on the s p i r i t which led to i t s advent. In order to do so systematically, I shall make a particular use of the word "i r r a t i o n a l i t y ".

I define as partaking of irr a t i o n a l i t y the amount by which the depiction departs from 40 what would be a normal r e a l i s t i c rendering of the event. Thus I include under irra t i o n a l i t y any amount of dehumanization or dematerialization, also anything which reveals i t s e l f to be abnormal, strange, odd, ambiguous, incongruous, dissonant, "irra t i o n a l " , inappropriate, i l l o g i c a l , untrue to l i f e , untrue to normal experience, anything which does not agree with the notion we have of a r e a l i s t i c , normal representation of the event.

It had resulted, for instance, from an interest in cl a r i t y and directness of expression as was the case in early Christian times ; i t had been used to promote Spi r i t u a l i t y ; i t had resulted from an interest in the things of nature as when animals, which we would normally not expect to be included, are inserted by the a r t i s t ; i t had resulted because the ar t i s t was interested in celebrating the fashion of the day as Ghirlandaio i s when he dresses b i b l i c a l figures in the costumes of the day , or because he wanted to please the arch-eologically-minded ones as Ghirlandaio does in his Adoration of the Shepherds Florence, S.

He i s concerned with avoiding the the provocation of such comments as: But here again the latter are not meant, as such, to arrest the mind. When he includes antique monuments in his Adoration of the Shepherds. Ghirlandaio expects that the in-congruity as such w i l l not impose i t s e l f on the beholder; he expects the latter to enjoy both the monuments and the scene of the Adoration without being disturbed by the obvious abnor-mality.

Wb'lfflin observes, in this context, that " a l l the romancing of the fifteenth century i s just a harmless game with architecture and dress. When Raphael, for instance, includes two youths climbing up one of the columns, in the Expulsion of Heliodorus. It i s meant to be simply by-passed. Indeed i t i s my contention that we can discern i n the new art a d i s t i n c t w i l l to awake feelings of abnormality, of incongruity, of dissonance, of i l l o g i c a l i t y , of ambiguity, of inconsistency, of strangeness i n the beholder. I r r a t i o n a l i t y i s no longer meant to be trans-lated nor to be by-passed, but, as such, to arrest the beholder's attention, to perplex and disturb him, to frustrate and b a f f l e him, and often to create malaise, discomfort and uneasiness in him.

Romanesque a r t , at times, achieves e f f e c t s resembling the ones achieved i n the new a r t. In the f i r s t chapter, we have defined Spirit u a l i t y as an ether breathing the presence of the S p i r i t of God, It i s of a fundamental importance, for an adequate understanding of the new w i l l , to understand how such an ether i s different from the one which irrat i o n a l i t y , as such, produces.

The latter, by defini-tion, i s made of abnormality, strangeness, ambiguity, i l l o g i -c a l ity, inconguity Now when these qualities as such strike the mind, we are not properly speaking in the domain of Sp i r i t u a l i t y , The latter is allowed to exist only when these qualities are translated by the mind. Thus a search for the abnormal, the strange, the ambiguous, the incongruous, the i l l o g i c a l.

We must also realize how any dwelling of the mind on the ir r a t i o n a l i t y as such is detrimental to the existence of Spi r i t u a l i t y. For in such a case the apprehension of irration-a l i t y in i t s very character of abnormality and strangeness tends to substitute i t s e l f to i t s apprehension as Sp i r i t u a l i t y.

Instead of being grasped as a s p i r i t u a l event, the l a t t e r tended to be grasped as a t r u l y "strange" event. Bernard's times, irr a t i o n a l i t y had come to be used in such a way that this very structure was endangered. Irrationality tended to become interesting to the mind in i t s very character of strangeness and abnormality, so that i t s translation into Spirituality tended to be no longer effective.

It i s against such a degeneration that the saint thundered. Now I am not denying here a certain concern for Spirit u a l i t y from the part of Pontormo and Rosso. Neither am I declaring that the new w i l l i s active in a l l of their works. I am only stating for the moment that in a large number of their works, along with the w i l l for Sp i r i t u a l i t y which I am conceding the new w i l l to awake feelings of abnormality, incongruity etc.

In some works, as said above, even the internal S p i r i t u a l i t y of the work i s annihilated by the irra t i o n a l i t y displayed; in others, as we shall see, the two wills can be f e l t separately. Thus as the Byzantine ar t i s t had endeavoured to bathe the event in Spirituality, the event, in the new art through the new w i l l , finds i t s e l f bathed in an atmosphere of abnormality, strangeness, incongruity, dissonance.

To the superior world created by the classic artist the new art substitutes strange and abnormal worlds partaking sometimes of the nightmare , where abnormality, dissonance, i l l o g i c a l i t y , ambiguity are the accepted values. I t would be a matter of great controversy to decide whether i t i s the new w i l l , the w i l l for a new S p i r i t u a l i t y or the w i l l for new aesthetic e f f e c t s which was the decisive one for the advent of the new ar t.

Although I am strongly inclined to believe i n the f i r s t hypothesis, my aim i n t h i s essay w i l l be limited f i r s t to showing the existence of the new w i l l i n Pontormo's and Rosso's ar t , and second to explaining what would have caused t h i s new w i l l to make i t s appearance. The "new art" s h a l l r e f e r exclusively to the art of Rosso and Pontormo discussed i n t h i s essay. He includes a sarcophagus next to the C h i l d , two antique p i l l a r s and a brand new triumphal arch i n the background.

The possible forces at work during the creative process are so numerous that they could never be enumerated com-p l e t e l y. Among the major ones are the desire to follow the p r e v a i l i n g fashion, the desire for fame, the desire to please the patron by giving him what he expects, the desire for o r i g i n a l i t y , the w i l l to impose S p i r i t u a l i t y , the w i l l to achieve new aesthetic e f f e c t s , the search f o r a new beauty I t i s obvious that some of these forces or drives play a more important part than others during the creative process, depending on the a r t i s t 1 s own temperament, his p a r t i c u l a r mood at the time of the sketching, the s o c i a l conditions of the time The works by Pontormo and Rosso which we s h a l l discuss embody a new aesthetic beauty, as said above, and t h i s i s no doubt, f i r s t of a l l , because being genuine a r t i s t s , they could not help producing i n beauty.

What I am con-tending i s that the w i l l to disturb, perplex and even shock the beholder was one of the major forces or drives at work during the creative process which led to t h e i r pro-duction. I would never claim that i t was the only one. This space i s e a s i l y apprehended, yet i t i s obviously not large enough to accouht for the abnormally reduced scale of Joseph and St, J 0hn, What i s more, Rosso ins e r t s i n the background a landscape which extends far into the distance, and which appears "normally recessive.

What further adds to t h i s c o n f l i c t i s that the figures are depicted with a s u f f i c i e n t l y great amount of naturalism: Thus here the a r t i s t emphasizes the incongruity between the figures and the world they inhabit, thereby creating an abnormality which tends to be disturbing. Freed-berg gives an impeccable description of this work. The head, however, has been strangely dislocated in respect both to the axis of the body and the vertical axis of the picture, and i t has been even more abnormally displaced in space, thrust preternaturally forward to the foremost plane.

It i s framed squarely by the lank long hair and by the hat, a f l a t floating biomorphic shape. In the background landscape, the topmost level of the trees continues the straight line of the hat, already singular enough, in an irrational connection between near and distant. Thus imminently disjoined from i t s context and compelled toward us, the face i s then subtly warped on i t s own axis, the far side pulled slightly toward the picture plane.

The eyes turn s t i l l more toward us and stare, the pupils sharp against the white, with an unbearably insistent gaze. This unpleasant communication i s a l l in one direction: We can look at him only with unease, and with the sense that associa-tion with him, even in this purely psychological domain of 50 ar t , might be dangerous; he i s a male and a n t i c l a s s i c a l inversion 4 of the Mona L i s a , " Elsewhere Freedberg points out the "almost dangerous abnormality 1' of his expression. The "subtle departure" from the normal, which I mentioned i n the preceding chapter, i s here unmistakable and i s meant to impose i t s e l f on us as such, and i n such a way that a concrete disturbance r e s u l t s.

We do not know what t h i s young man has i n mind, but i t does not seem reassuring to us. We sense abnormal ideas going on i n his mind and that i s why h i s staring at us makes us f e e l that "association with him,.. This work i s the more s i g n i f i c a n t that by i t s being a purely secular work, there cannot be any question of S p i r i t u a l i t y i n the sense defined above. The new w i l l , here, dominates unchal-lenged. Pontormo had con-tributed the V i s i t a t i o n In the context of the l a t t e r and the other depictions such as the Birth of the V i r g i n by Andrea , which are a l l e s s e n t i a l l y c l a s s i c , "almost the f i r s t impression that emerges from the Rosso i s of i t s bizarre types and their expressions: It is easy here, indeed, to detect a will to truly shock the beholder by imposing on him, after the refinement and ennoblement of reality present in the other frescoes, a true crudity of types and an aggressive affirmation of these types through the spilling of the robe.

What is more, Rosso clothes his figures in truly monumental draperies, even more monumental than in the adjacent Visitation by Pontormo, and recalling the ones used by Andrea in his nearby , o Adoration of the Magi It is as i f Rosso had wanted to make a parody of the monumental figures depicted in the nearby frescoes: The latter remark applies especially to the two figures on the far right, to the one facing the middle figure and turned almost completely toward us, looking up with his mouth opened, and to the one at the far left.

Thus Rosso in this work creates a double conflict, a double incongruity, fi r s t by juxtaposing crude figures to the idealized ones of the adjacent frescoes, and second by dressing them in clothes which rationally and conspicuously do not belong 52 to them. The atmosphere emanating i s one of c o n f l i c t , of contradiction, of incongruity, not of S p i r i t u a l i t y. Like was the fashion i n c l a s s i c a r t , the figures are set i n a shallow but r a t i o n a l three-dimensional space. They stand quite com-for t a b l y i n conventional attitudes.

John the Baptist, Mary and the Child an easiness and relaxation of pose which are p e c u l i a r l y c l a s s i c. The bodies of those f i g -ures are also remarkably well proportioned and rounded out. The figures of St. Jerome, on the r i g h t , throws a s t r i k i n g note of discordance i n the work. His outstanding skinniness and the abnormal elongation of his neck contrast di s t u r b i n g l y with the roundness of the other figures. He i s a man, indeed, whom we would not f e e l safe with.

Rosso makes him the f o c a l point of the work by turning three of the figures including the Virgin towards him and depicting him as i f he was explaining something to them. The casualness with which the V i r g i n i s l i s t e n i n g to him could make us think that he i s r e a l l y not dangerous, but the abnormality of f a c i a l expression which they a l l share makes us conclude, on the contrary, that i n a l l p r o b a b i l i t y they a l l fundamentally belong to the same abnormal humanity as he does and are most l i k e l y inhabited by the same untrustable feelings as he i s.

Freedberg observes that they 53 wear "an a i r of j u s t perceptible genteel lunacy which, i n a moment, could become hysteria or shapeless psychological collapse And indeed the general impression i s of a strange, abnormal humanity. The magenta goes "changeant" to blue i n shadows; one sleeve i s curiously transformed by l i g h t to yellow-gold. The John Baptist i s red-haired, clad i n a mantle of pale rose, bleached white i n h i g h l i g h t s , which contrasts with the tones of blue white, grey, and dark green of h i s other gar-ments.

The browned body of Jerome opposite i s draped in blue, very dark i n shadow and very cool i n light. Jerome and i n the psy-chological expression of the figures i n general to make the l a t t e r look s t i l l more strange and abnormal. And how s t i l l further away from S p i r i t u a l i t y could the work have stood i f the church master who had commissioned i t had not expressed his utter disapproval, whi'lk i t was s t i l l i n progress.

Accordingly the master rushed out of the house and refused to take the picture, saying that he had been deceived.

Dadaist crisis in the sixteenth century - UBC Library Open Collections

The f i r s t one i s the remarkable easiness with which a s t r i k i n g l y abnormal and disturbing element often brings out i n i t s very character of abnormality and strangeness the i r r a -t i o n a l i t y of the other i r r a t i o n a l e l ements present i n the work — and how such i r r a t i o n a l elements which would not be otherwise disturbing thus activated, contribute to make the work pulsate with abnormality and strangeness s t i l l more. The scheme of colors, for instance, which i s used on the figures of the S. Nuova A l t a r would not have the same effect on the beholder's mind i f used on a group of Byzantine figures.

Nuova A l t a r on a group of fi g u r e s , which s t r i k e through the peculiar abnormality of t h e i r f a c i a l expression, i t s i r r a t i o n a l i t y somehow seems to come out i n i t s very character of abnormality and dissonance and contributes to 5 5 make the figures look s t i l l more "strange" and abnormal. And we ean be sure that the a r t i s t knew and was r e l y i n g on that phenomenon. The second phenomenon I want to point out has already been indicated. Jerome have normal proportions and there i s an easiness 56 in the postures of St. John, the Virgin and the Child which as observed above i s typically classic.

The two infants at the bottom also strike by their innocence and the gentle ideal-ization which Rosso imposed on them. On this background of rationality and idealism, the demoniac-looking figure of St. Jerome, the dissonance of the scheme of colors, and theaabnor-mality of f a c i a l expression which the figures except the two infants at the bottom a l l share are thus imposed on us with a greater acuity than would be the case i f , for instance, a l l the figures were immeasurably elongated and set in an utterly i r r a -tional space. In this case, the disturbing elements of the S. Nuova Altar would be easily "swamped11 in the ir r a t i o n a l i t y present and would attract the attention far less than they do in the actual work.

Indeed the world of the S. Nuova Altar as are the worlds of the other works by Rosso which are discussed here i s Ear from possessing the naivety of medieval art, for instance. It plays on the beholder's sense of normality, of logic, of con-gruity in a way which i s a l l but naive and which allows us to deduce in a l l fairness an utterly positive willingness in Rosso to disturb, shock and frustrate the beholder.

The w i l l to impose actual discomfort on the beholder, which had been f u l l y active in the Portrait of a Young Man discussed above i s given free course again in the Madonna with Sts. The space i n which the figures are set i s here again quite r a t i o n a l. The Child c l i n g s to his mother i n a natural way and his proportions are normal. Yet look at the way her r i g h t arm surrounds the Child and how i t appears "nightmarishly" melting into his body; and look at the long and sharp fingers on both of her hands: Now compare the looks on the faces of St.

Bartholomew and the V i r g i n. There i s something frightening i n them. These people seem to belong to a race of abnormals, not of the innocent kind, but of the dangerous one, with an i n t e l l i g e n c e which has been di s t o r t e d. The way the V i r g i n and Bartholomew look at us indeed makes us f e e l uncomfortable. The Child himself seems devoured by some strangely c o n f l i c t i n g inner urges.

He seems to be of the same breeding as the two saints yet they have learned to repress momentarily t h e i r i n s t i n c t s as he has not. The sharpness of the l i g h t modelling these figures gives them a somewhat metallic appearance and adds to the night-marish atmosphere of the scene.

Nuova A l t a r the abnormality 58 and strangeness p r e v a i l i n g did not reach us d i r e c t l y but t h e o r e t i c a l l y remained confined to the work, here i t aggres-s i v e l y breaks the barrier between the world of the picture and our world to impose on us a concrete uneasiness and discomfort. The Deposition Volterxa Museum; dated i s another s t r i k i n g example of the new w i l l. The f i r s t incongruity we s h a l l observe i s between the upper and the lower parts.

At the bottom, a scene of desolation and sadness. The V i r g i n , sustained by two la d i e s , bows her head i n a d i r e c t i o n completely p a r a l l e l to the ground, i n a sign of ultimate despair but also resignation: The Magdalena, also overcome with g r i e f , i s resting her head on Mary's lap. John, on the r i g h t , i s bowing deeply, also with his head p a r a l l e l to the ground. For him also the struggle i s over. What i s happening above them i s a masterpiece of confusion and noisy a c t i v i t y. Christ's body i s sustained by a man i n quite precarious a position on his ladder.

The one holding his legs i s bent away from the ladder on which he i s r e s t i n g. Moreover, we cannot determine whether his r i g h t foot i s resting on the ladder or not, for i t i s hidden behind one of the women's head. The only way he i s apparently supported i s by having his l e f t knee resting on one of the ladder's steps, and t h i s gives him, s t i l l more than to the f i r s t man described, a most precarious p o s i t i o n.

Furthermore, he looks away from Christ's body as i f 59 about to bring himself back into a more secure and stable posi-t i o n on the ladder. The man next to him, with his mouth wide opened and his arms pointing at C h r i s t , i s shouting something at the man across him. We cannot determine exactly what i t i s , although he i s probably warning him to be c a r e f u l , seeing the precarious position t h i s man i s i n. As to the man on top, he i s supervising the operations with a worried and excited look, which the f l y i n g band of his robe, on top of him, only contributes to emphasize.

We f i n d ourselves actually worrying about those men's a c t i v i t i e s: How about the one holding Christ's legs: I t seems here that Rosso had wanted to a t t r a c t our attention on the d i f f i c u l t i e s involved i n taking a body down a cross, rather than on the fact that i t i s Christ's body which i s being taken down.

This idea i s further emphasized by the fact that a l l the figures are exclusively intent on t h e i r job, which i s to take a body down, without dropping i t: To emphasize the d i s t i n c t i o n between the upper and lower 60 parts, Rosso makes a l l the actors i n the lower scene act as i f unaware of the d i f f i c u l t i e s involved i n the upper scene. Even the boy holding the ladder, whom we would expect to be looking up and i n t e n t l y following the operations, seems unconcerned about them.

The r e s u l t of such a disun i t y between the two scenes the upper scene i s noisy and secular, while the lower one i s s i l e n t and r e l i g i o u s i s to lead our eye up and down, making us unable to decide whether we should stay down and sympathize with the mourners, or go up and j o i n i n the rescue operations. The atmos-phere immediately created by t h i s d i s u n i t y i s one of c o n f l i c t and incongruity: Looking more i n t e n t l y at the upper scene, we observe that Christ's body i s i n such a position that the hand which must belong to the man supporting him grasping the cross, could as we l l be H i s i The unusual smile on Christ's face, combined with t h i s ambiguity, now makes us doubt whether He i s r e a l l y dead and we begin to wonder whether the whole thing i s not simply a macabre joke: The incongruity be-tween the upper and lower scenes which was r a t i o n a l l y incom-prehensible now finds i t s explanation within the i r r a t i o n a l i t y which the nightmare allows.

John, who i s much t a l l e r than the other figures and bows his head 6X quite out of the picture. Without the mechanism released by the problematic s i t u a t i o n of C h r i s t , his abnormal stature and his breaking out of the picture plane would not be so disturbing, but now we are made more aware of i t and the strangeness thereby created imposes i t s e l f as such to make the whole event look s t i l l more strange and nightmarish.

Most of the l a t t e r are depicted quite normally, both p h y s i c a l l y and psychologically. He looks outward with an a i r somewhat timid and unsure, which only emphasizes the ambiguity of his s i t u a t i o n. The saint on the extreme r i g h t , on the other hand, looks at us menacingly. His body i s turned as i f he was about to leave, yet he takes at us a l a s t glance i n which we f e e l a certain threat to our security. Bernard's hands, while the proportions of the other saints are pl a u s i b l e , i s also a highly disturbing element.

He i s one of the saints i n most evidence and the abnormal elongation of his r i g h t hand, es p e c i a l l y , throws a note of unpleasant discordance and abnormality i n the work. I t seems indeed that Rosso could not r e s i s t the temptation to insert disturbing elements.

This work, for instance, would be highly consistent and pleasant without the abnormalities enumerated above; the l a t t e r , as i t were, " s p o i l " the atmosphere of calm and n o b i l i t y which would be p r e v a i l i n g otherwise. The action here i s set i n a deep three-dimensional space, which i s conveyed by the juxtaposition of p a r a l l e l layers one behind another.

The figures, i n general, have average proportions and t h e i r gestures approximate f a i r l y plaus-i b l y the ones of normal human beings. The head of the man i n the r i g h t foreground gives the effect of an isolated sphere; 1 6 the base of the column which stretches under the body of the man shouting does not con-tinue; the s i t u a t i o n of the sheep i s most ambiguous: The impression we get, once we have noticed those disturbing elements, i s of a world which i s neither u t t e r l y unreal nor s a t i s -f a c t o r i l y r e a l but reveals i t s e l f as an unusually strange one.

We are perplexed and unconsciously t r y to f i n d a solution to the unresolved i r r a t i o n a l elements. The new w i l l i n t h i s work has indeed achieved i t s purpose perhaps as successfully as i n the ones described above: The a t t r i b u t i o n and dating of t h i s work are taken from Freedberg, op. But i t i s , l e t us say, a refined awareness. The boundary i n the Rosso i s broken, on the contrary, with aggression.

Vasari, The Lives of the Painters. Sculptors, and Architects, t r. Hinds, London, , I I , p. Their degree of excellence runs high within the c l a s s i c t r a d i t i o n. Freedberg remarks that "with these two works Pontormo carried the postulates of c l a s s i c a l style that had been given to him to a kind of f u l f i l l m e n t no other a r t i s t i n the c i t y had as yet attained and which, i n t h i s kind, no other a r t i s t would surpass.

Here i s an a r t i s t who succeeds along with others of course i n bringing the e f f o r t s of a whole century to a climactic consummation and who the next day abandons his former ideals and starts off i n a completely d i f f e r e n t d i r e c t i o n. We a l l know how under the influence of Savonarola, t h i s a r t i s t disregarded his own achievements i n order to impose an uncompro-mising S p i r i t u a l i t y on his a r t.

The difference between B o t t i c e l l i ' s and Pontormo's approach, i s , however, fundamental. Pontormo, on the contrary, often takes pleasure, as we s h a l l see, i n crowding his figures i n a space "not quite" s u f f i c i e n t or l o g i c a l for them, or i n challenging our sense of location, with the r e s u l t that feelings of ambiguity, incongruity, and i l l o g i c a l i t y a l l detrimental to the apprehension of S p i r i t u a l i t y are awakened i n us. Indeed while B o t t i c e l l i ' s late art reveals a clear search for the s p i r i t u a l , Pontormo's, from around onwards, on the whole reveals primarily a search for the strange, the incongruous, the perplexing, the disturbing.

In several of his works, as we have seen, S p i r i t u a l i t y was the least of Rosso's concerns. Consequently the new w i l l was given free course and was often allowed to run w i l d. Pontormo's art i n general does not produce the discomfort and uneasiness which we have observed i n Rosso's. Further, while Rosso favored an abnormal humanity and nightmarish e f f e c t s , Pontormo favours to challenge the beholder's sense of consistency, which had been so highly developed under the impact of c l a s s i c a r t ; to t h i s end, he devises such formal disturbances as s p a t i a l ambiguities or incongruities, the conspicuous tipping of a t r i a n g l e , the lack of unity, p h y s i c a l l y or psychologically, among the figures This d i f f e r e n t i a t i o n does not apply by any means to a l l of these a r t i s t e works, but i t gives an idea of their respective approach.

What must be kept i n mind at any rate i s that i n both e x i s t s fundamentally the same w i l l: One of the f i r s t works by Pontormo i n which the new w i l l manifests i t s e l f d i s t i n c t l y i s the so-called Joseph Sold to Potiphar of the Borgherini series Henfield, Lady Salmond; ca. We see them about to leave, i n the background, while Jacob, i n the fore-5 ground, i s giving Benjamin his permission to accompany them. There i s c e r t a i n l y i n t h i s work an abundance of secondary figures and a certain confusion which make i t depart from c l a s s i c norms.

Pontormo has arti c u l a t e d i t with one fi g u r e , but i t i s impossible to determine exactly where the l a t t e r stands. There i s no appreciable i n t e r v a l of distance between him and the foreground figures. We know through his diminished proportions that he stands away from them, yet his exact location eludes us.

Now t h i s would not perhaps be so disturbing i f he was occupied at some minor a c t i v i t y , but Pontormo places him conspicuously i n the exact center of the picture. And t h i s i s as complete a manifestation of the new w i l l as could be. We are perplexed and disturbed by t h i s f i g u r e ; we would want to integrate him with the r e s t , yet we are powerless. He imposes h i s presence on us through h i s staring at us yet he eludes us and does not allow himself to be grasped.

B r i e f l y , t h i s work depicts the coming to Egypt of Joseph's family and Jacob's blessing 8 ' of Joseph's sons. Pontormo has made of i t a masterpiece of formal ambiguity, i l l o g i c a l i t y and incongruity. The space defined 69 i n the foreground i s clear enough and inhabited quite comfortably by the figures included i n i t. The mind here i s not disturbed. The scale given to these figures i n general, i n these s p a t i a l areas, i s s u f f i c i e n t l y decreasing as the figures recede into deep space to appear pla u s i b l e.

The Joseph i n the middle of the s t a i r s i s smaller i n size than the Joseph i n the foreground and larger than the figure of Asenath at the top of the s t a i r s. However, the space between the man holding out an empty bowl with an imploring gesture and the a r c h i t e c t u r a l construction i n the background defies any r a t i o n a l analysis.

The scale of the mass of people held back by the two guards has diminished so d r a s t i c a l l y that they should normally stand much further back i n space, yet there i s no i n d i c a t i o n along the ground that t h i s i s so. And look at the isol a t e d figure immediately behind them, standing against the wa l l below the s t a i r s: This figure i s the exact counterpart of the isolated figure i n the middle ground of the Joseph Sold to Potiphar.

UBC Theses and Dissertations

In both cases, a man standing by himself, looking outwards, not p a r t i c i p a t i n g i n the event a c t i v e l y and i n a completely ambiguous si t u a t i o n as f a r as his position i n space i s concerned. I t seems that i n both of these cases, Pontormo has included such a figure 9 mainly to simply baffle the beholder's sense of location. Wischnitzer observes that the landscape does not recede into depth but r i s e s l i k e a screen.

I t i s further reinforced by the complete absence of s p a t i a l a r t i c u l a t i o n immediately behind the upper part of the s t a i r s: The l a t t e r impression i s further reinforced by the effect created by the statues. Freedberg observes that they are "imminently as animate 13 as the actors. We wonder indeed i n what kind of a world Pontormo i s transporting us. The key to i t s mystery i s given to us by the si t u a t i o n of the group of people held back by the two guards. Unusual groupings of t h i s kind were quite common i n medieval a r t.

Here the soldiers are unnaturally pressed together behind 71 the figure of Ch r i s t ; but so are the f l e e i n g apostles on the r i g h t ; moreover the scale of a l l those figures i s consistent and also we do not f e e l any actual uneasiness amongst them. Consequently, the i r r a t i o n a l i t y thereby created does not as such tend to perplex the mind and no actual disturbance r e s u l t s. In the Joseph i n Egypt, on the other hand, two major factors combine to make the group held back by the soldiers t r u l y disturbing.

F i r s t , the d r a s t i c a l l y reduced size of those figures compared to the one of the figures i n the foreground. Second, the p a r t i c u l a r uneasiness which, on careful observation, we perceive amongst them, compared to the ease with which the figures move i n the rest of the canvas. Of course, t h e i r eagerness to appreach Joseph and the fact that two guards are holding them back p a r t l y explains t h i s uneasiness, but not quite s u f f i c i e n t l y.

Beside t h i s genuine eagerness and the con-t r o l exercised by the guards, we f e e l the presence of another power at work, a t r u l y physical power which seems to press on the figures and group them together i n a ti g h t e r way than they would normally allow themselves to be grouped: Since there i s no v i s i b l e force other than the soldiers surrounding them, the resu l t we come to i s that space i t s e l f i s t r u l y closing on them.

Once we are aware of t h i s , i t i s to t h i s strange power act i v a t i n g space i t s e l f that we now attribute the a b i l i t y to change the natural appearance of things. And the animate aspect of the statues now appears to be the work 72 not of our imagination but of t h i s power. The whole scene now seems to breathe the presence of t h i s power. We now f e e l that the " r a t i o n a l i t y " included i n the work i s at the mercy of the l a t t e r and that i n the next instant, the characters depicted i n the foreground could f i n d themselves re-duced to the same scale as the figures i n the middle ground and background.

We would not be surprised, e i t h e r , i f the statues suddenly began to move. The world which Pontormo offers us here suddenly reveals i t s e l f as u t t e r l y transitory, subject to r a d i c a l changes at any moment. The control which medieval art allowed through i t s naivety and which c l a s s i c art did not prevent throu i t s respect of the basic laws of nature i s here l o s t.

The be-holder finds himself confronted here with a world regulated by incomprehensible laws and activated by powers as incomprehensible. His sense of consistency and congruity finds i t s e l f openly baffled The new w i l l has triumphed. The works by Pontormo so far discussed were intended for private use. Michele Visdomini; dated Sp. John Infant and two p u t t i , i n the upper corners, also balance each other. The use of the triangular form, grouping Mary, St. Francis, Joseph and St. John Evangelist i s also discernable. One 73 p e c u l i a r i t y about i t i s that i t i s tipped; moreover, one of i t s extremities l i e s outside the frame.

Further, i f brought back to normal p o s i t i o n , i t s base would be too wide to be contained within the canvas. For these reasons i t i s not immediately graspable but a closer examination reveals i t as an almost perfect t r i a n g l e. The apex i s j u s t above Mary's head, about half-way between the top of her head and the upper frame. One side goes through St.